Pigtail-Assisted Distal Canalicular Repair in a Child: An Innovative Technique for Bicanalicular Intubation With Single Monocanalicular Stent

© 2024 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Objective. Repair of medial canthus injury involving canaliculus is an emergency indication for canalicular intubation to restore lacrimal drainage. Herein, the author has described an innovative but simple technique for this reconstruction.

Method and Result. A small, blunt pigtail probe was gently passed through the opposite canaliculus in a rotational manner. A silicon stent was threaded inside canaliculi by reverse rotation of the pigtail in an atraumatic way. The technique was used on 4 pediatric cases without any postoperative complication or epiphora.

Conclusions. This technique of intubation is simple, cheap, and useful in canalicular emergencies, including "distal" canaliculus lacerations.

Introduction

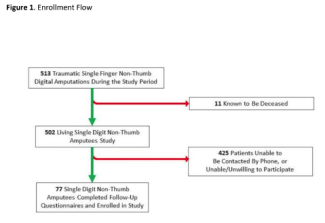

Various methods to repair canalicular laceration, with the help of pigtail probe or intubation, have been described in the literature.1 Yet "distal" canalicular lacerations could be more challenging in children due to their relatively small faces. This report describes an innovative modified technique, discovered incidentally while operating on a similar laceration in a child (Figure 1, A-C).

Figure 1. (A-I) A left lower lid avulsion from the medial canthus. (B) Follow up at first day of pigtail-assisted repair. (C) At 12 weeks. (D-I) Canalicular laceration (D-F, left upper; G-I, left lower) repaired in another 2 children by same technique with follow-up at postoperative day 1 and at 12 weeks.

Technique, Methods, and Results

Under general anesthesia, left lower lid avulsion from the medial canthus angle with full-thickness laceration about 15 mm along the lower lid crease was noted. Under operating microscope under high magnification, the wound was explored for cut ends of the lacerated lower canaliculus. The punctum was dilated and probed till proximal cut end, which measured about 8 mm. The distal cut end, which otherwise appeared as an opening with rolled out "white" edges, was not visible, and the classically described "bubble test" also failed.2 This could be due to significant maceration, some necrosis, or healing by granulation tissues leading to altered soft-tissue textures and retraction or closure of the cut end (stump).

As it was taking longer than expected and only a self-retaining monocanalicular silicon stent (Aurostent, Aurolab) was available, intubation was attempted with the help of a blunt-ended, Beyer pigtail probe (Figure 2, A-C). The stent was threaded inside the lower punctum and canaliculus up to the proximal cut end and secured by its collarette at the punctum. The upper punctum was dilated, and the small pigtail probe was introduced inside the upper canaliculus and common canaliculus, following the natural passage with gentle countertraction and effortless counterclockwise rotation until the stump was encountered. The free end of the stent was threaded in eye of the pigtail probe, and the probe was rotated clockwise backwards until the threaded end was recovered from the upper punctum (Supplemental material, Video). A 4-0 silk with taper needle over a rubber peg was passed through skin in the upper limb of the medial canthal tendon, then to the corresponding cut edge of the lid including skin in the thick bite, then back in a vertical mattress fashion, and tied loosely over the peg. Adjacent necrotic tissues were carefully resected, and the orbicularis layer was repaired from inside with a few interrupted 6-0 polyglactin sutures anterior to the stent. Healthy edges of the canaliculus were opposed by passing a few interrupted 8-0 polyglactin sutures in pericanalicular healthy tissue. Thereafter, the silk suture was tightened by final tie. Extra length of the stent was cut flush to the upper punctum so that it retracted inside the canaliculus. Skin side of the wound margin was refreshened by removing necrotic and granulation tissue and repaired with interrupted sutures in 2 layers, 6-0 polyglactin for orbicularis and 6-0 silk for skin. On follow up, 6-0 silk, 4-0 silk, and stent were removed in outpatient clinic at weeks 1, 3 and 12, respectively (Figure 1, A-C). Subsequently, 3 children received similar operations (Figure 1, D-I). During the follow-ups, none of the 4 patients reported having epiphora or any other problem.

Figure 2. (A) Aurostent and blunt-ended, pigtail probe with (B) small and (C) long ends (counterclockwise, A-C).

Discussion

Various methods have been described in literature to identify the distal cut-end or stump, each claimed by their inventors to be very successful. In the authors' opinion, it depends upon surgeon's choice, availability of the instruments, patient factors (eg, age, amount of trauma, severity, previous lacrimal surgery), and the method best suited to each scenario. Hence, the merits or demerits have been written from each author's perspective. Injection of air, water, dye, colored solution, or viscoelastic requires a closed system that might not be attainable always.2 Dyes could stain other tissues as well and make identification difficult. Fiber-optic (23G), acupuncture needle, or epidural catheter is usually not easily available in every oculoplastic theater.3,4 Cho et al have described a probe-push technique via the opposing canaliculus; however, it necessitates the identification of the "deep medial cut end" based on its appearance, which can be challenging in cases of necrosis or macerated tissues.5 It entails nasolacrimal probing, which is risky if nasal injury is not detected.

The idea, in the present technique, is quick, simple stenting of canaliculi, without entering the sac, with an atraumatic or blunt pigtail probe. To accomplish this, a clear impression of fine anatomy of the medial canthus region, with some learning curve, is obligatory. As common canaliculus average length is 1.2 mm (sometimes up to 3-5 mm), it is crucial to rotate the pigtail before it is supposed to enter the sac, which lies underneath common limb of medial canthal tendon (MCT).6 Because common canaliculus is absent in 10% of the population, this technique might fail in those patients due to a long, narrow intra-sac canaliculus.1,7 The canaliculi usually lies in the pretarsal orbicularis layer but sometimes in the subcutaneous or preorbicularis plane. Hence, anatomically the common canaliculus represents confluence (angle, 50°) of upper and lower canaliculi (or accompanying pretarsal orbicularis, or limbs of MCT) at the level of common limb of MCT.6 An imaginary meeting point of curvilinear upper and lower lid crease, just deep to the medial limit of caruncle at medial commissure, can be used as surface marking for the same (Figure 3). On retrospective review of the literature, a similar method has been described where a "polypropylene guide" was used, which can be omitted.8 Instead, directly pulling the folded stent (ie, twice the silicon tube diameter, 2 × 0.64 = 1.28 mm) did not pose any problem, while retrieving from the opposite punctum due to distensible (0.5-1 mm up to 2 mm) canalicular passage.1 This results in "bicanalicular" intubation using a "monocanalicular" stent. The "flush cutting" was done without pulling the stent to avoid over-shortening it, which decreases the risk of early stent loss.9

Figure 3. Schematic pencil diagram representing applied anatomical relationship. The corresponding surface markings from the authors' perspective, in a separate normal left eye, drew lid creases (green lines) and pretarsal orbicularis fibers (yellow lines) are projected to meet at MCT or medial palpebral ligament (white line).

To conclude, the pigtail-assisted technique can be considered a rapid, feasible, and reproducible yet safe option, especially for pediatric distal canalicular repair.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Ms. Shilpi Gupta for sketching work.

Authors: Gautam Lokdarshi, MD, MRCS1; Abdul Shameer Shamanzil, MD, MRCS2

Affiliations: 1Oculoplastic and Ocular Oncology Services, IRIS Superspeciality Eye Hospital, Orchid Medical Centre, Ranchi, India; 2Dr. Rajendra Prasad Centre for Ophthalmic Sciences, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

Correspondence: Gautam Lokdarshi, MD, MRCS; gdarshiaiims@gmail.com

Ethics: An informed consent was taken from the patient for publishing data, including clinical photographs and video. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Disclosures: The authors disclose no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests.

References

1. Mauriello JA. Unfavorable Results of Eyelid and Lacrimal Surgery: Prevention and Management. Butterworth-Heinemann; 2000: 361, 477-490.

2. Loff HJ, Wobig JL, Dailey RA. The bubble test: an atraumatic method for canalicular laceration repair. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;12(1):61-64. doi:10.1097/00002341-199603000-00010

3. Peng W, Wang Y, Tan B, Wang H, Liu X, Liang X. A new method for identifying the cut ends in canalicular laceration. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43325. doi:10.1038/srep43325

4. Liang X, Liu Z, Li F, et al. A novel modified soft probe for identifying the distal cut end in single canalicular laceration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97(5):665-666. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302605

5. Cho SH, Hyun DW, Kang HJ, Ha MS. A simple new method for identifying the proximal cut end in lower canalicular laceration. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2008;22(2):73-76. doi:10.3341/kjo.2008.22.2.73

6. Hurwitz JJ. The Lacrimal System. Lippincott-Raven; 1996: 16-19.

7. Kakizaki H, Takahashi Y, Miyazaki H, et al. Intra-sac portion of the lacrimal canaliculus. Orbit. 2013;32(5):294-297. doi:10.3109/01676830.2013.815227

8. Forbes BJ, Katowitz WR, Binenbaum G. Pediatric canalicular tear repairs--revisiting the pigtail probe.J AAPOS. 2008;12(5):518-520. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2008.05.006.

9. Mangan MS, Turan SG, Ocak SY. Pediatric canalicular laceration repair using the Mini Monoka versus Masterka monocanalicular stent. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2023;86(1):46-51. doi:10.5935/0004-2749.20220084