Novel Treatment of Pyoderma Gangrenosum With Porcine-Derived Extracellular Matrix Following Bilateral Latissimus Dorsi Breast Reconstruction: A Case Report

© 2024 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a rare disease characterized by ulcerative cutaneous lesions that can occur postoperatively and is often associated with autoimmune disorders. PG is diagnosed by excluding other conditions that can cause ulcerations, such as infections, which may also result in immunosuppressive treatment delays and suboptimal wound care. Operative debridement of wounds has traditionally been avoided in the acute setting secondary to pathergy. This article presents a case of extensive breast PG that was successfully treated with surgical debridement, porcine-derived extracellular matrix, and negative pressure wound therapy while on systemic immunosuppressive therapy.

Introduction

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a rare inflammatory neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by extensive ulcerative cutaneous lesions. The etiology is unknown, but wounds can be precipitated by dermal injury and are often associated with autoimmune disorders such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and rheumatoid arthritis.1-4 PG is diagnosed clinically by excluding other conditions that can cause ulcerations, such as infections, vasculitis, malignancy, or soft tissue ischemia. It is particularly challenging to diagnose in the postoperative period, which may result in immunosuppressive treatment delays and suboptimal wound care. In this patient population, PG typically presents in the first postoperative week as a tender erythematous nodule that evolves into painful ulcerations with irregular, raised, violaceous borders.2-7 The patient may also have fever, leukocytosis, and sterile exudate from wounds.2 Skin biopsy can be helpful in making the diagnosis of PG. Histopathology shows nonspecific neutrophilic inflammation and wound cultures are typically negative.2, 4-8 A high index of suspicion and early diagnosis facilitate timely intervention.2 The mainstay of treatment is immunosuppression with topical and systemic medications including corticosteroids, dapsone, clofazimine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, and TNF-alpha inhibitors.5-9 Operative debridement of wounds has traditionally been avoided in the acute setting secondary to pathergy.10

Deep wounds can be debrided and treated with negative pressure wound therapy, allograft, autograft, or flap coverage during the quiescent phase if the patient is adequately immunosuppressed.2,6-8,11-12 Despite treatment, patients can experience a chronic relapsing disease course.6-8

PG has rarely been described in patients undergoing breast reduction and breast reconstruction surgery.2-3,10,13-14 Most patients develop symptoms within 3 to 4 days of surgery, but the median time to correct diagnosis is 12.5 days.2-3

The breasts are typically affected symmetrically, and the nipples are spared.2 Donor sites such as the abdomen or back may also be involved.2,4 In cases of flap reconstruction, skin changes on the flap may be mistaken for flap ischemia or infection leading to debridement and subsequent flap loss.3 In addition to prompt medical management, maintaining the aesthetic appearance of the breast is a priority in this patient population. Reconstruction has largely been limited to local wound care and healing by secondary intention, which can leave patients with disfiguring scars.5,7,10 Skin grafting and reconstruction with flaps has been utilized in a small number of patients but carries with it risks of pathergy at the donor and/or recipient site.2 Porcine urinary bladder matrix has been described for use in pyoderma gangrenosum ulcers.15 To our knowledge, it has not been utilized in breast PG.

We present a case of extensive breast PG that was successfully treated with surgical debridement, porcine-derived extracellular matrix, and negative pressure wound therapy while on systemic immunosuppressive therapy. This novel treatment approach can be utilized in patients to prevent pathergy and optimize aesthetic outcomes.

Case

A 38-year-old, otherwise healthy female with no history of autoimmune disorders underwent bilateral immediate breast reconstruction with buried latissimus dorsi flaps after bilateral mastectomies for ductal carcinoma in-situ and Paget disease of the nipple. Intraoperative indocyanine green angiography was performed to evaluate perfusion to the mastectomy skin flaps once the latissimus dorsi flaps were buried. An area of decreased perfusion on the right inferior mastectomy flap was identified and sharply excised prior to closure. The patient initially recovered well and was discharged on postoperative day 3. She returned to the hospital on postoperative day 9 due to fever and painful ulcerations with fibrinous exudate on her bilateral breasts involving approximately 25% to 50% of her bilateral mastectomy skin.

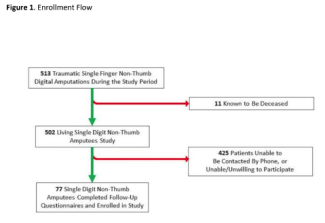

The patient was initially treated with intravenous antibiotics and local wound care due to suspicion for infection; however, the ulcerative lesions continued to progress. Within 48 hours she was started on topical and systemic steroid treatment (prednisone 1 mg/kg/day), which was continued over the next 12 days with noticeable improvement. Skin biopsies showed significantly ulcerated skin with underlying neutrophilic infiltrate and necrosis without the presence of bacteria. Tissue cultures were also negative for microorganisms. Dapsone was added for medical treatment of PG. The bilateral breast wounds demarcated to discrete areas of necrosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Necrotic bilateral breast wounds prior to treatment.

Figure 2. (A) Bilateral breast wounds following sharp debridement of necrotic tissue. (B) Bilateral breast wounds following application of double layer porcine-derived extracellular matrix.

Once adequately immunosuppressed, the patient was able to undergo operative debridement of all necrotic tissue (Figure 2A and 2B). To expedite wound healing, double layer porcine-derived extracellular matrix (ACell, Inc) was applied to the wound bed in combination with negative pressure therapy. The patient underwent 2 additional applications of the porcine-derived extracellular matrix in the outpatient clinic setting. Dapsone was continued and prednisone was tapered over the course of 12 weeks.

The patient ultimately went on to completely heal her bilateral breast wounds by 11 weeks post debridement with no evidence of pathergy (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Complete healing of bilateral breast wounds 11 weeks following debridement and application of double layer porcine-derived extracellular matrix with no evidence of pathergy.

Discussion

PG is a rare but potentially devastating complication after surgery. The core tenets of treatment are early recognition, immunosuppression, and avoidance of pathergy in the acute setting. To date, advances in local wound care and surgical reconstruction of PG wounds have been limited.

Porcine urinary bladder matrix (UBM) is derived from porcine urinary bladder mucosa and provides a scaffold for cell migration and proliferation in wound beds. It has been proven to promote wound healing and inductive tissue remodeling by modulation of inflammation.16 Initial studies have shown reduced healing time and rates of recurrence in diabetic foot ulcers.17 UBM has also been utilized in treatment of burns, free flap donor sites, and full-thickness soft tissue defects.18,19,20

There is 1 case report in which a lower extremity wound from PG was treated successfully with porcine UBM, negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), and ultimately a split-thickness skin graft.21 To our knowledge, UBM has not been applied in breast reconstruction in the setting of PG.

This novel intervention is well suited for patients with PG in aesthetically sensitive areas. The immune modulating properties of UBM work synergistically with NPWT, which has been shown to increase vascular ingrowth, reduce edema, and improve cellular proliferation.21 Furthermore, the risk of pathergy is mitigated by reducing surgical manipulation with flap or graft reconstruction.

UBM is available in several formulations, including powder and single or multi-layer sheets. The powder consists of small particles that can be placed in irregularly shaped wounds. The single or multi-layer lyophilized sheets are ideal for packing into deep wounds or for resurfacing large, superficial defects. Sutures can be placed through the sheets to effectively secure them to the wound bed, facilitating neovascularization. A sterile environment is not required for application; thus, this can be performed in an office setting. In addition to ease of use, patients have improved pain control with reduced frequency of dressing changes.

In our patient, the combination of UBM and NPWT resulted in complete healing and an aesthetically acceptable result without the need for additional procedures. Further research is needed to assess the utility of UBM and NPWT in the treatment of partial- and full-thickness wounds, particularly in patients who are not optimal surgical candidates for traditional methods of reconstruction.

Conclusions

PG can be a challenging and deforming disease with limited treatment options and can often lead to prolonged wound care and frequent hospitalizations. Our patient developed extensive bilateral breast PG wounds that were effectively treated with short healing time with a novel combination of systemic immunosuppression, debridement, porcine-derived extracellular matrix, and negative pressure therapy.

Acknowledgments

Authors: Kristen Whalen, MD; Nicole K. Le, MD, MPH; Jake Laun, MD; Lauren Kuykendall, MD

Affiliation: Department of Plastic Surgery, Morsani College of Medicine, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida

Correspondence: Kristen Whalen, MD; kswhalen@usf.edu

Ethics: Human subjects have given informed consent for the use of images. This research has conformed to appropriate institutional guidelines, including an approved study by the University of South Florida Institutional Review Board.

Disclosures: The authors disclose no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests.

References

1. Laun J, Elston JB, Harrington MA, Payne WG. Severe bilateral lower extremity pyoderma gangrenosum. Eplasty. 2016;16:ic44.

2. Ehrl DC, Heidekrueger PI, Broer PN. Pyoderma gangrenosum after breast surgery: A systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2018;71(7):1023-1032.

3. Momeni A, Satterwhite T, Eggleston JM. Postsurgical pyoderma gangrenosum after autologous breast reconstruction: case report and review of the literature. Ann Plast Surg. 2015;74(3):284-288.

4. Guaitoli G, Piacentini F, Omarini C, et al. Post-surgical pyoderma gangrenosum of the breast: needs for early diagnosis and right therapy. Breast Cancer. 2019;26(4):520-523.

5. MacKenzie D, Moiemen N, Frame JD. Pyoderma gangrenosum following breast reconstruction. Br J Plastic Surg. 2000;53(5):441-443.

6. Rozen S, Nahabedian M, Manson P. Management strategies for pyoderma gangrenosum: case studies and review of literature. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;47(3):310-315.

7. Ahronowitze I, Harp J, Shinkai K. Etiology and Management of Pyoderma Gangrenosum. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13(3):191-211.

8. Gameiro A, Pereira N, Cardoso JC, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:285-293.

9. Patel F, Fitzmaurice S, Duong C, et al. Effective strategies for the management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:525-531.

10. Singh P, Tuffaha SH, Robbins SH, Bonawitz SC. Pyoderma gangrenosum following autologous breast reconstruction. Gland Surg. 2017;6(1):101-104.

11. Fulbright RK, Wolf JE, Tschen JA. Pyoderma gangrenosum at surgery sites. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1985;11:883-886.

12. Tuffaha SH, Sarhane KA, Mundinger GS, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum after breast surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;77(2):e39-e44. doi:10.1097/sap.0000000000000248

13. Davis MD, Alexander JL, Prawer SE. Pyoderma gangrenosum of the breasts

precipitated by breast surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(2):317-320.

14. Zelones JT, Nigriny JF. Pyoderma gangrenosum after deep inferior epigastric perforator breast reconstruction. Plast Reconst Surg Glob Open. 2017;5(4):e1239. doi:10.1097/gox.0000000000001239

15. Dillingham CS, Jorizzo J. Managing ulcers associated with pyoderma gangrenosum with a urinary bladder matrix and negative-pressure wound therapy. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2019;32(2):70-76. doi:10.1097/01.asw.0000546120.32681.bc

16. Paige J, Kremer M, Landry J, et al. Modulation of inflammation in wounds of diabetic patients treated with porcine urinary bladder matrix. Futuremedicine.com. Published April 25, 2019. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.futuremedicine.com/doi/10.2217/rme-2019-0009?url_ver=Z39.88003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub++0pubmed

17. Alvarez O, Smith T, Gilbert T, et al. Diabetic foot ulcers treated with porcine urinary bladder extracellular matrix and total contact cast: interim analysis of a randomized, controlled trial. Index Wounds. 2017;29(5):140-146.

18. Shanti RM, Smart RJ, Meram A, Kim D. Porcine urinary bladder extracellular matrix for the salvage of fibula free flap skin paddle: technical note and description of a case. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2017;10(4):318-322. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1593473

19. Kraemer B, Geiger S, Deigni O, Watson JT. Management of open l,ower extremity wounds with concomitant fracture using a porcine urinary bladder matrix. Index Wounds. 2016;28(11):387-394.

20. Kim JS, Kaminsky AJ, Summitt JB, Thayer WP. New innovations for deep partial-thickness burn treatment with ACell MatriStem Matrix. Adv Wound Care. 2016;5(12):546-552. doi:10.1089/wound.2015.0681

21. Dillingham CS, Jorizzo J. Managing ulcers associated with pyoderma gangrenosum with a urinary bladder matrix and negative-pressure wound therapy. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2019;32(2):70-76. doi:10.1097/01.asw.0000546120.32681.bc