Carcinoma Cuniculatum of the Maxilla Mimicking Nonhealing Extraction Sockets at the Right Molar Region – An Interesting Case

Abstract

Background. Carcinoma cuniculatum is a rare variant of squamous cell carcinoma, mostly affecting the skin but also sparsely reported to occur in the oral cavity. Oral carcinoma cuniculatum (OCC) tends to be misdiagnosed as verrucous carcinoma; this may lead to inadequate treatment and recurrence due to the locally aggressive nature of the tumor. This report presents the case of a 56-year-old man with a progressively enlarging painful OCC at the maxillary right molar region, exhibiting both exophytic (red, soft, nodular mass) and endophytic (superficial ulceration and bone exposure, mimicking nonhealing extraction sockets) growth patterns. Incisional biopsy was consistent with OCC, a diagnosis that was corroborated through histopathologic examination of the resected specimen. The patient underwent en bloc resection (segmental maxillectomy) of the tumor and prosthetic rehabilitation with an obturator and remains disease-free 2.5 years postoperatively.

Conclusions. The aim of this report is to provide a thorough clinical imaging and histopathological presentation of OCC along with a brief literature review to highlight the difficulties of accurate diagnosis and the pitfalls in treating this uncommon entity.

Introduction

Oral carcinoma cuniculatum (OCC) is a rare variant of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) that possesses similar clinicopathological findings and clinical course with cutaneous carcinoma cuniculatum, first described and reported1 to involve various sites (ie, face, esophagus, abdomen, lower extremities, penis, and cervix). Flieger and Owinski (1977) were the first to report OCC2 without establishing an association with OSCC, mainly because of its distinct histological architecture (well-differentiated epithelium without or with minimal atypia) and less aggressive behavior.

According to both the 2005 and 2017 World Health Organization (WHO) classifications of tumors, OCC represents a rare, independent, locally aggressive subtype of OSCC. OCC is characterized by keratin-filled branching crypts and keratin cores like rabbit burrows (hence the term “cuniculatum” from the Latin word for rabbit), lined by well-differentiated, hyperplastic, stratified squamous epithelium with minimal atypia, extending deep into the connective tissue and potentially invading adjacent bone that only rarely induces nodal or distant metastases.3,4

The diagnosis of OCC remains challenging because of clinicians’ lack of familiarity with this entity, leading to underdiagnosis and a deceptively low incidence.5 The correlation of histopathological findings with clinical and radiological features is crucial to its diagnosis and differentiation from other histological subtypes of OSCC, such as verrucous carcinoma (VC) and papillary OSCC.5 Misdiagnosis of OCC as VC is reportedly common, due to not only overlapping clinical features (papillomatous keratinized surface) but also inadequate (superficial and/or non-representative) sampling during biopsy; however, given the local aggressiveness of OCC and particularly its propensity to invade bone, misdiagnosis as VC may lead to inadequate treatment and local recurrence.4-6

The objective of this article is to present the authors’ experience in treating an interesting case of OCC, affecting the posterior maxilla of a 56-year-old male patient. Furthermore, a review of the literature has been conducted to illustrate the clinical features, imaging and histopathological findings, treatment strategies, and overall biological behavior of this rare subtype of OSCC, with the goal of optimizing diagnostic and therapeutic decisions.

Methods

A 56-year-old male patient was referred to the authors’ department by his attending dentist for evaluation of nonhealing extraction sockets within a progressively enlarging, painful, nodular mass with superficial ulceration at the maxillary right molar region. Teeth 15, 16, and 17 had been extracted 2 months before his referral due to class 2 motility attributed to periodontal disease. The patient had received multiple short courses of oral antibiotics, including amoxicillin, metronidazole, and clindamycin.

The patient’s medical history was remarkable for type 2 diabetes, arterial hypertension, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He had a 30-pack-year smoking history but did not consume alcohol. Intraoral examination showed a 3 × 2 cm red, exophytic, nodular mass extending from the buccal gingivae of tooth 14 and exhibiting class 1 motility to the mucosa of the maxillary tuberosity and hard palate. A superficial ulceration was observed adjacent to the extraction socket of tooth 16; thus, the growth pattern of the lesion was both exophytic and endophytic. On palpation, the tumor was soft and bled profusely. Extraoral inspection was unremarkable. Neck examination did not reveal palpable cervical lymph nodes.

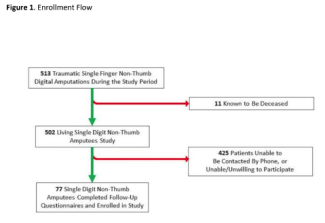

Panoramic radiograph demonstrated a relatively well-delineated osteolytic radiolucent lesion that extended from the upper right first premolar to the upper right third molar (between teeth 14 and 18) that had eroded the right maxillary sinus floor (Figure 1).

The patient was submitted to incisional biopsy under local anesthesia 2 days after his first visit; the histopathology report was consistent with OCC.

Computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast showed a poorly defined osteolytic lesion of the right posterior maxilla that widely involved the maxillary sinus and extended anteriorly to tooth 14 and posteriorly up to the pterygoid process of the sphenoid without infiltrating it (Figure 2). No cervical lymph node pathology was demonstrated on CT of the neck. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a relatively high-intensity area within the right maxilla that extended anterioposteriorly for 3 cm from the premolar region to the maxillary tuberosity, cephalocaudally for 2 cm from the pterygoid process of the sphenoid to the alveolar crest, and buccally/palatally for 1.5 cm, widely involving the right maxillary sinus.

Given the malignant nature of the tumor, further investigation consisted of CT of the chest and abdominal ultrasound, neither of which yielded any pathological findings. Thus, the tumor was staged as T4N0M0. Results of laboratory studies (including complete blood count, biochemical profile, and coagulation tests) were within normal limits.

Segmental maxillectomy extending from tooth #12 anteriorly to the maxillary tuberosity posteriorly and up to the lower third of the pterygoid process of the sphenoid was performed 25 days after the patient’s initial examination. A free full-thickness skin graft, harvested from the right supraclavicular area, was placed in the defect along with an obturator.

Results

Histopathology revealed complex proliferation of a highly differentiated, stratified, squamous epithelium with keratin-filled crypts resembling rabbit burrows. The mitosis rate of the epithelial cells was normal, and only mild atypia was evident. Inflammatory response in the stroma with an infiltration of lymphocytes and neutrophils was also noted (Figures 3 and 4).

The postoperative course of the patient was uneventful, and a strict follow-up was scheduled. The patient underwent facial skull and neck CT scans 6 and 18 months postoperatively that showed no local recurrence or nodal metastasis, respectively. Today, 2.5 years postoperatively, the patient remains clinically and radiographically disease-free and has recovered his speech and swallowing function.

Discussion

OCC has been included in the 2005 and 2017 WHO classifications as a rare, independent variant of OSCC. According to a 2018 systematic review by Farag et al, a total of 55 cases of OCC have been reported from 1954 to 2018,7 while a 2021 literature review by Yadav et al identified fewer than 75 cases of carcinoma cuniculatum in the head and neck region, including the larynx.8 Since most clinicians are not familiar with this entity, OCC tends to be misdiagnosed, leading to inadequate treatment and potentially fatal outcomes.4-6

OCC has been described to affect patients of a wide age range but predominantly affecting those in the sixth and seventh decades of life.3,4,7 Data concerning the male-to-female ratio of patients with OCC remain conflicting, suggesting either a surprising slight female predilection7,9 or the opposite.3-6,8 OCC most commonly involves the gingivae/alveolar mucosa of the mandible and maxilla, followed by the hard palate, tongue, mandible, and buccal mucosa.3-5,7

OCC appears with such symptoms as pain or soreness, swelling, and restricted tongue mobility with difficulty in swallowing and articulation.3,7 The tumor’s growth pattern, reflected by its clinical presentation, may be: a) exophytic, appearing as a nodular, pebbly, cobblestone, verrucous, or cauliflower-like mass with or without induration; b) endophytic or invasive, inducing ulceration and bone exposure or mimicking periodontal disease (ie, gingival inflammation, bleeding, tooth motility, and bone loss); or c) both endophytic and exophytic in varying ratios.4-7 Moreover, OCC may appear as white patches or leukoplakia and erythroleukoplakia.4-6 The patient in this case report exhibited both an extended exophytic and a more restricted endophytic component. The patient reported a history of class 2 mobility of his upper right molars, which was attributed to periodontal disease and led to multiple extractions. Subsequent nonhealing of the extraction sockets, along with gingival inflammation that failed to respond to antibiotics, compelled the dentist to recommend evaluation by a maxillofacial surgeon.

Given the locally aggressive/invasive nature of OCC, thorough deep sampling from multiple sites of the suspected lesions during biopsy is crucial to avoid underdiagnosis.5,6,8,10 The lack of atypia and presence of keratin-filled burrows in superficial and/or limited specimens may mislead the histopathologist to assume an either reactive or hyperplastic nature of the lesion. Consequently, the most common misdiagnosis is verrucous hyperplasia with hyperkeratosis, VC, or papillary and well-differentiated OSCC.4-6 When intraosseous, OCC is frequently misdiagnosed as an odontogenic keratocystic tumor, dental abscess, or osteomyelitis.3,11 Therefore, thorough clinicopathologic correlation is mandatory.

OCCs are depicted in CT scans as both well-defined and ill-defined tumors, causing cortical erosion and/or cancellous destruction of the adjacent bone while primarily affecting the soft tissues.4,7,11 MRI shows tumors of heterogeneous intensity, causing gingival inflammation but sparing the extrinsic muscles, when located at the tongue. Panoramic radiographs, used as a screening tool, usually reveal ill-defined, irregular osteolytic radiolucent lesions infiltrating the cortical and cancellous bone and involving anatomic structures, such as the nasal floor, sinus walls, or mandibular canal.5 In this case, the tumor had infiltrated not only the adjacent bone but also the right maxillary sinus floor, extending widely into the sinus.

OCC has a distinctive histοlogical appearance, with well-differentiated squamous epithelium that extends deep into the connective tissue with multiple, branching, keratin-filled crypts (described as rabbit burrows), absent or mild cytological atypia (usually limited to the basal and parabasal layers), and normal to little mitoses; inflammatory stromal reaction, mainly consisting of lymphocytes and neutrophils, may be observed, along with discharging abscesses.4,7,9 This patient exhibited most of the histological hallmarks of OCC.

Although both smoking and alcohol are well-documented predisposing factors of oral malignancy, no clear association between OCC and tobacco or alcohol consumption has been established.5,6 OCC also reportedly occurs in pre-existing premalignant conditions (eg, leukoplakia, erythroplakia, lichen planus), suggesting malignant transformation.4,9 In 2011, Suzuki et al implicated chronic irritation by prosthesis,6 while a 2021 report by Yadav et al first highlighted the potential role of betel nut chewing as a predisposing factor of OCC in patients of Indian origin.8 The patient in the current case report had a 30-pack-year smoking but no history of significant alcohol use.

Although a correlation between human papillomavirus and cutaneous carcinoma cuniculatum has been suggested in the literature,12 the role of the virus in the pathogenesis of OCC remains unclear.5,6,13 P53 immunoexpression in OCC has been occasionally investigated with discordant results5,13; similarly, Ki-67 expression in the basal and suprabasal layers of the OCC epithelium has been studied with conflicting results.7,8 Presumably, further research on the immunohistochemical findings of OCC is required.

Complete surgical resection with a safety margin is considered the treatment of choice for OCC.6,7,9 The locally aggressive nature of OCC, attributed to its deep epithelial projections to the connective tissue, may complicate surgical treatment.4,6 Segmental or subtotal maxillectomies/mandibulectomies have been performed in cases of extensive tumors because of OCC’s tendency for local invasion. In this case, the tumor had widely infiltrated the right maxillary sinus but not the pterygoid process, thus warranting segmental maxillectomy to achieve clear margins of at least 5 mm circumferentially.

OCC has rarely been associated with regional (cervical lymph node) and/or distant (lung) metastases.8,9,11 This should always be taken under consideration and investigated thoroughly before establishing appropriate treatment.11 However, to date, there has been no clinical evidence that selective neck dissection confers oncological benefit (improved regional control or cancer-specific survival) in the management of OCC, given its very low risk of nodal metastasis.4-6 No neck dissection was considered mandatory for this patient, given the lack of either clinical or imaging findings to suggest nodal metastasis.

The role of chemotherapy and radiotherapy in the treatment of OCC remains controversial and needs to be further investigated.3,7,10,11 Local recurrence with more resistant and aggressive behavior than the primary OCC has been reported, rarely followed by malignant transformation and regional or distant metastasis.9 Repeated surgical resection is usually qualified as the treatment of choice for recurrent cases, while chemotherapy and radiotherapy should be used cautiously because OCC does not seem to respond to the former, and the latter presumably induces anaplastic transformation.6,9,10

Conclusions

In conclusion, OCC is a rare, well-differentiated variant of OSCC with distinct clinical and histopathological findings. Although presenting a relatively good prognosis with low recurrence and metastasis rate after appropriate surgical treatment, it may show resistant behavior in recurrent cases. Adequate knowledge of its diagnostic criteria along with thorough correlation of histopathology with clinical and imaging findings is crucial for its early diagnosis and proper treatment.

Acknowledgments

Affiliations: 1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Dental School, University of Athens, Greece; 2Department of General Surgery, KAT General Hospital of Athens, Greece; 3Department of Dermatology, Evangelismos General Hospital of Athens, Greece

Correspondence: Schoinohoriti Ourania, MD, DDS, MSc, PhD; our_schoinohoriti@yahoo.com

Ethics: The patient, here presented, was fully informed and gave his written consent for publication of this specific case report.

Funding: No financial support has been received.

Disclosures: The authors disclose no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests.

References

1. Aird I, Johnson HD, Lennox B, Stansfeld AG. Epithelioma cuniculatum a variety of squamous carcinoma peculiar to the foot. Br J Surg. 1954;42(173):245-250. doi:10.1002/bjs.18004217304

2. Flieger S, Owiński T. [Epithelioma cuniculatum an unusual form of mouth and jaw neoplasm]. Czasopismo Stomatologiczne. 1977;30(5):395-401. Accessed November 4, 2022. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/266444/

3. Pons Y, Kerrary S, Cox A, et al. Mandibular cuniculatum carcinoma: apropos of 3 cases and literature review. Head Neck. 2010;34(2):291-295. doi:10.1002/hed.21493

4. Padilla RJ, Murrah VA. Carcinoma cuniculatum of the oral mucosa: a potentially underdiagnosed entity in the absence of clinical correlation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;118(6):684-693. doi:10.1016/j.oooo.2014.08.011

5. Allon D, Kaplan I, Manor R, Calderon S. Carcinoma cuniculatum of the jaw: A rare variant of oral carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol. 2002;94(5):601-608. doi:10.1067/moe.2002.126913

6. Suzuki J, Hashimoto S, Watanabe K, Takahashi K, Usubuchi H, Suzuki H. Carcinoma cuniculatum mimicking leukoplakia of the mandibular gingiva. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2012;39(3):321-325. doi:10.1016/j.anl.2011.06.004

7. Farag AF, Abou-Alnour DA, Abu-Taleb NS. Oral carcinoma cuniculatum, an unacquainted variant of oral squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review. Imaging Sci Dent. 2018;48(4):233. doi:10.5624/isd.2018.48.4.233

8. Yadav S, Bal M, Rane S, Mittal N, Janu A, Patil A. Carcinoma cuniculatum of the oral cavity: a series of 6 cases and review of literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2022 Mar;16(1):213-223. doi:10.1007/s12105-021-01340-6

9. Sun Y, Kuyama K, Burkhardt A, Yamamoto H. Clinicopathological evaluation of carcinoma cuniculatum: a variant of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011;41(4):303-308. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01116.x

10. Shapiro MC, Wong B, O’Brien MJ, Salama A. Mandibular destruction secondary to invasion by carcinoma cuniculatum. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73(12):2343-2351. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2015.05.034

11. Zhang C, Hu Y, Tian Z, Zhu L, Zhang C, Li J. Oral carcinoma cuniculatum presenting with moth-eaten destruction of the mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018;125(4):e86-e93. doi:10.1016/j.oooo.2018.01.008

12. Wastiaux H, Dreno B. Recurrent cuniculatum squamous cell carcinoma of the fingers and virus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(5):627-628. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02416.x

13. Thavaraj S, Cobb A, Kalavrezos N, Beale T, Walker DM, Jay A. Carcinoma cuniculatum arising in the tongue. Head Neck Pathol. 2011;6(1):130-134. doi:10.1007/s12105-011-0270-2

References

1. Aird I, Johnson HD, Lennox B, Stansfeld AG. Epithelioma cuniculatum a variety of squamous carcinoma peculiar to the foot. Br J Surg. 1954;42(173):245-250. doi:10.1002/bjs.18004217304

2. Flieger S, Owiński T. [Epithelioma cuniculatum an unusual form of mouth and jaw neoplasm]. Czasopismo Stomatologiczne. 1977;30(5):395-401. Accessed November 4, 2022. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/266444/

3. Pons Y, Kerrary S, Cox A, et al. Mandibular cuniculatum carcinoma: apropos of 3 cases and literature review. Head Neck. 2010;34(2):291-295. doi:10.1002/hed.21493

4. Padilla RJ, Murrah VA. Carcinoma cuniculatum of the oral mucosa: a potentially underdiagnosed entity in the absence of clinical correlation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;118(6):684-693. doi:10.1016/j.oooo.2014.08.011

5. Allon D, Kaplan I, Manor R, Calderon S. Carcinoma cuniculatum of the jaw: A rare variant of oral carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol. 2002;94(5):601-608. doi:10.1067/moe.2002.126913

6. Suzuki J, Hashimoto S, Watanabe K, Takahashi K, Usubuchi H, Suzuki H. Carcinoma cuniculatum mimicking leukoplakia of the mandibular gingiva. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2012;39(3):321-325. doi:10.1016/j.anl.2011.06.004

7. Farag AF, Abou-Alnour DA, Abu-Taleb NS. Oral carcinoma cuniculatum, an unacquainted variant of oral squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review. Imaging Sci Dent. 2018;48(4):233. doi:10.5624/isd.2018.48.4.233

8. Yadav S, Bal M, Rane S, Mittal N, Janu A, Patil A. Carcinoma cuniculatum of the oral cavity: a series of 6 cases and review of literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2022 Mar;16(1):213-223. doi:10.1007/s12105-021-01340-6

9. Sun Y, Kuyama K, Burkhardt A, Yamamoto H. Clinicopathological evaluation of carcinoma cuniculatum: a variant of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2011;41(4):303-308. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.2011.01116.x

10. Shapiro MC, Wong B, O’Brien MJ, Salama A. Mandibular destruction secondary to invasion by carcinoma cuniculatum. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73(12):2343-2351. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2015.05.034

11. Zhang C, Hu Y, Tian Z, Zhu L, Zhang C, Li J. Oral carcinoma cuniculatum presenting with moth-eaten destruction of the mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018;125(4):e86-e93. doi:10.1016/j.oooo.2018.01.008

12. Wastiaux H, Dreno B. Recurrent cuniculatum squamous cell carcinoma of the fingers and virus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(5):627-628. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02416.x

13. Thavaraj S, Cobb A, Kalavrezos N, Beale T, Walker DM, Jay A. Carcinoma cuniculatum arising in the tongue. Head Neck Pathol. 2011;6(1):130-134. doi:10.1007/s12105-011-0270-2