Orofacial Clefting in Van der Woude’s Syndrome

Questions

1. What is the etiology based on the history and physical examination?

2. Describe the embryology associated with orofacial clefts.

3. What kind of treatment team is needed for orofacial clefts, and how do the team members work together?

4. Describe the surgical treatment timeline and goals for orofacial clefts.

Case Description

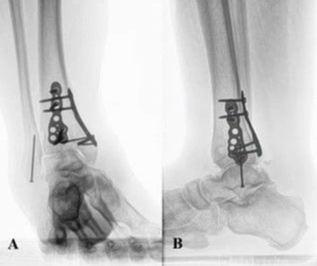

A 5-month-old male infant is brought to the cleft clinic for evaluation of a unilateral complete left cleft lip, palate, and bilateral lower lip pits (Figure 1). The patient was born at 40 weeks’ gestation to a gravida 2, para 2 mother via cesarean delivery because of multiple fetal anomalies. Prenatal care started at 17 weeks and was sporadic. The patient’s brother has also been treated for cleft lip, palate, and bilateral lower lip pits. The patient’s mother has provided pictures of the older sibling’s clinical course for reference (Figure 2).

Q1. What is the etiology based on the history and physical examination?

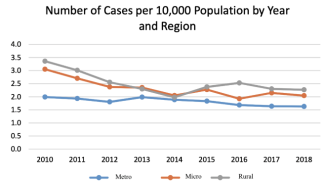

Cleft lip and palate (CLP) are among the most common congenital defects of the orofacial region, affecting 1:500, 1:1000, and 1:2000 live births of Asian, Caucasian, and African ancestries, respectively. Male offspring are affected more frequently than female.1 Cleft localization favors the left side relative to the right side in a 2:1 ratio for unilateral cleft lips (CLs). Etiologies of CLP are divided into nonsyndromic and syndromic categories.

Nonsyndromic orofacial clefts account for 70% of CLP cases and 50% of all cleft palate (CP) cases. These cases are multifactorial, and no genetic cause has been identified. Risk factors for nonsyndromic clefting include smoking, alcohol use, and pharmacologic exposures.2 If one child or parent has CLP, there is a 4% chance of clefting in subsequent pregnancies. This risk increases if two children (9%) or one child and one parent (17%) have CLP.3

Syndromic CLP occurs in fewer than 15% of cases, and these are associated with chromosomal abnormalities.4 Van der Woude syndrome (VDWS) is one of the most common syndromes associated with CL and frequently involves CP. It is caused by interferon regulatory factor 6 (IRF6) mutations and is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion with variable penetrance. VDWS is associated with accessory salivary glands (lip pits) and may present with abnormal genitalia, syndactyly, popliteal pterygia, and missing second molars (Figure 3).5 In this case, the patient’s mother reported that the infant’s older sibling had been treated surgically for VDWS. Other conditions that present with orofacial clefting include Waardenburg syndrome, Stickler syndrome, Apert syndrome, Treacher-Collins syndrome, Down syndrome, Edward syndrome, and Patau syndrome.4

Q2: Describe the embryology associated with orofacial clefts.

Facial development commences in gestation week 3 when neural crest cells undergo a mesenchymal transition and migrate to frontonasal and visceral arch regions, forming 5 primordia: frontonasal (1), maxillary (2), and mandibular (2) prominences. The proliferation of mesenchymal tissue at the nasal placodes of the frontonasal prominence forms medial and lateral nasal prominences. In gestation week 5, the fusion of medial and lateral nasal prominences forms the upper lip philtrum and median palatine process (premaxilla) of the primary palate anterior to the incisive foramen. Fusion of the 2 medial nasal processes forms the nasal septum and intermaxillary lip segment. The following week, the fusion of the maxillary process and lateral nasal prominences forms the remaining lateral upper lip groove. In week 7, continued downward growth of the maxillary prominence results in the lateral palatine shelves. During gestation weeks 8 through 11, midline fusion of the lateral palatine shelves begins at the incisive foramen and moves posteriorly, forming the secondary palate. By the end of gestation week 12, there is a fusion between the primary palate, nasal septum, and secondary palate. Despite frequently occurring together, the embryologic origins of CL and CP are distinct. CL occurs due to the failure of maxillary and nasal processes to fuse on one or both sides. CP occurs due to failure of lateral palatine process fusion. CLP always involves the primary palate but has variable involvement in the secondary palate. However, CP involves the secondary palate only. Consequently, mispositioning of muscles must be accounted for during primary repair (Figure 4).

Q3. What kind of treatment team is needed for orofacial clefts, and how do the team members work together?

A multidisciplinary team is needed for optimal care of patients with orofacial clefts.6 The multidisciplinary model allows audiology, nursing, psychology, social work, and speech pathology to work in concordance with dental specialties, genetics, otolaryngology, pediatrics, plastic surgery, and psychiatry to manage their respective fields and address the cleft.

The primary goal of treating children with CLP is to repair the defect at a safe age. Initial assessment includes ultrasound examination in the prenatal period to detect cleft lips. Additional information is gathered regarding family history, teratogenic exposures, and genetic counseling to guide the diagnosis. Earlier identification during this time facilitates formation of the health care team to be involved and prompt development of treatment strategies. Geneticists and pediatricians are consulted immediately after birth for children with orofacial clefts for feeding instructions, counseling, and diagnosis for adequate oral intake and weight gain while awaiting definitive lip and palate repair. The multidisciplinary team works to achieve a plan for normal speech, language, hearing, functional occlusion, and dental health during the first week of life. Emphasis is also placed on meeting developmental milestones and addressing psychological stressors. Care is coordinated to minimize the number of surgeries performed and maximize the benefit of each surgery to the patient.

Q4. Describe the surgical treatment timeline and goals for orofacial clefts.

The optimal timing of primary orofacial cleft surgery has been controversial and depends on the patient’s individual circumstances. Historical criteria for timing of orofacial cleft repair follow the “Rule of Tens”: including 10 weeks old, 10 pounds in weight, and hemoglobin of 10 mg/dL.7 The American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association (ACPCA) recommends that CL repair occur within 6 to 12 months and primary CP repair occur within 18 months.8 The American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) recommends that primary CL repair occurs between 2 and 6 months, and CP repair should take place between 9 and 18 months.9 In particular circumstances like syndromic conditions, an orofacial cleft repair can be delayed for systemic concerns (Figure 5). Surgery for the presenting patient was scheduled to be performed at 10 months for complete cleft lip repair and cleft rhinoplasty repair at 17 months for straight-line two-flap palatoplasty and right buccal fat flap. The special indications of VDWS include excision of the congenital lip sinuses for either cosmetic reasons or recurrent inflammation after CLP repair. For this patient, this procedure was delayed until the child was 3 years of age due to social reasons (Figure 6). In addition, excision of the sinus tract may be done to avoid fistula formation to mucous glands, creating mucoid cysts.

The goals for orofacial cleft surgery include the closure of the cleft, attaining velopharyngeal competence, preventing recurrent otitis media, and ensuring adequate facial growth. In addition, closure aids in attaining symmetry and preventing aerophagia and oronasal regurgitation. Velopharyngeal competence is acquired by increasing the palatal length and repositioning muscles, ultimately leading to contact of the velum against the posterior pharynx. Myringotomy with tympanostomy tube placement is frequently performed simultaneously as primary cleft repair, which aids in preventing recurrent otitis media. Palate repair in early childhood can adversely affect maxillary growth, but this drawback is outweighed by improvements in speech achieved by early correction. Additionally, maxillary growth restriction can be corrected with orthognathic surgery during adolescence.10

Summary

VDWS is an autosomal dominant syndrome and one of the most common conditions associated with CLP. Because VDWS is associated with lip pits and accessory salivary glands, excision of the congenital lip sinuses is indicated in addition to CLP repair for cosmetic reasons and to prevent recurrent inflammation and the formation of mucoid cysts.

Acknowledgments

Affiliations: 1West Virginia University School of Medicine, Morgantown, WV; 2West Virginia University Department of Surgery, Division of Plastic Surgery, Morgantown, WV

Correspondence: Zachary A Koenig, MD; zakoenig@hsc.wvu.edu

Disclosures: The authors disclose no financial or nonfinancial conflicts of interest.

References

1. Watkins SE, Meyer RE, Strauss RP, Aylsworth AS. Classification, Epidemiology, and Genetics of Orofacial Clefts. Clinics in Plastic Surgery. 2014;41(2):149-163. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2013.12.003

2. Cheshmi B, Jafari Z, Naseri MA, Davari HA. Assessment of the correlation between various risk factors and orofacial cleft disorder spectrum: a retrospective case-control study. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;42(1):26. doi:10.1186/s40902-020-00270-7

3. Alois CI, Ruotolo RA. An overview of cleft lip and palate. Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2020;33(12):17-20. doi:10.1097/01.JAA.0000721644.06681.06

4. Beriaghi S, Myers S, Jensen S, Kaimal S, Chan C, Schaefer GB. Cleft Lip and Palate: Association with Other Congenital Malformations. Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry. 2009;33(3):207-210. doi:10.17796/jcpd.33.3.c244761467507721

5. Rizos M. Van der Woude syndrome: a review. Cardinal signs, epidemiology, associated features, differential diagnosis, expressivity, genetic counselling and treatment. The European Journal of Orthodontics. 2004;26(1):17-24. doi:10.1093/ejo/26.1.17

6. Tervo RC, Chudley AE. Management of cleft lip and palate: a team approach. Can Fam Physician. 1981;27:1964-1970.

7. Chow I, Purnell CA, Hanwright PJ, Gosain AK. Evaluating the Rule of 10s in Cleft Lip Repair: Do Data Support Dogma? Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2016;138(3):670-679. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000002476

8. Parameters For Evaluation and Treatment of Patients With Cleft Lip/Palate or Other Craniofacial Differences. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2018;55(1):137-156. doi:10.1177/1055665617739564

9. Cleft Lip and Palate Repair. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Accessed January 22, 2022. https://www.plasticsurgery.org/reconstructive-procedures/cleft-lip-and-palate-repair

10. Gürsoy S, Hukki J, Hurmerinta K. Five-Year Follow-Up of Maxillary Distraction Osteogenesis on the Dentofacial Structures of Children With Cleft Lip and Palate. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2010;68(4):744-750. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2009.07.036