Call the Bomb Squad: An Interesting Case of a Retained Explosive in the Mouth

© 2023 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Questions

1. What is the epidemiology of firework-related injuries?

2. What characteristics of the facial skeleton are important to consider when managing firework injuries to the face?

3. What are the initial management strategy and surgical considerations for the plastic surgeon regarding firework injuries to the face?

4. What are the major causes of early and long-term morbidity following facial reconstruction from firework injuries?

Case Description

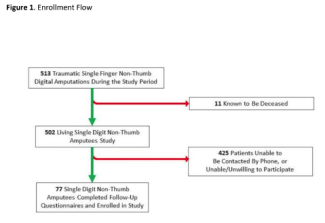

A 23-year-old man presented after a mortar misfired and propelled the ignited aerial shell of a firework toward his face, becoming lodged in his left jaw. His neighbor, a veteran and previous combat medic, expeditiously applied pressure and wet rags to prevent the ignited aerial shell from exploding. The patient was intubated upon arrival at the hospital, and after being stabilized, imaging was obtained (Figure 1).

As the ignited aerial shell had yet to explode, the bomb squad was notified. Using explosive precautions, a tracheostomy was performed to allow improved access and careful removal of the undetonated explosive (Figure 2). The nonviable tissue was excised, and the patient was secured in premorbid occlusion. Mini-plates were used to approximate comminuted segments. A large, spanning reconstruction plate was shaped and placed across all fractures. Bone allograft was used to fill defects, and the wound was closed primarily (Figures 3 and 4). Further operations were required for additional bone grafting, perioral contracture release, scar revisions, and removal of the submandibular gland due to recurrent ranula formation.

Three years after the initial operation, the patient appeared on the local news due to his tremendous recovery with restored facial volume, mimetic function, and oral competence, with minimal scarring (Figure 5).

Q1. What is the epidemiology of firework-related injuries?

Fireworks are used to celebrate cultural and religious events and festivities across the world. Unfortunately, fireworks are a frequent cause of accidental injury, especially to the untrained individual. In 2020, 15600 people were treated in emergency rooms for firework injuries and 66% of these injuries occurred in the month around the July 4th holiday.1 These injuries are most common in males and those under the age of 20 and are most often the result of device misuse, failure, or illegal use.2,3 While most firework-related injuries are minor and are treated in the emergency department, around 7.5% of patients are hospitalized for further treatment.3 Nearly 80% of all firework injuries occur to the head/neck and shoulder/upper extremity regions, given their proximity when lighting the explosives.4 Roughly two-thirds of firework injuries result in burns, followed by contusions and lacerations.3

Q2. What characteristics of the facial skeleton are important to consider when managing firework injuries to the face?

Firework injuries to the face are especially challenging given the severe implications facial trauma can have on airway maintenance and vital organs.5 The bony skeleton of the face protects these vital organs, and management of facial fractures must focus on preventing further injury to these important structures.6

Understanding the mechanics of blast injuries to the facial skeleton is helpful when planning for reconstructive intervention. Blast injuries, like those from fireworks, result in a blast wave that accelerates through the density of the bone with shearing forces that cause fractures.7 The middle third of the face, comprised of air-filled spaces, experiences injury via implosion, resulting in a “crushed eggshell” appearance made from several small, comminuted fragments of the maxillary and ethmoid bones, cribriform plate, and orbital floor.7

The lower third of the face consists of the mandible, which is highly exposed and is one of the most commonly injured bones in the face. It is associated with many important structures including the maxilla, temporomandibular joints (TMJs), dentition, salivary glands, motor and sensory nerves, and musculature of the head and neck, which are all at risk with mandibular fractures.8,9 Because the architecture of the mandible contributes significantly to the projection of the face, it can be challenging to reconstruct to restore both function and aesthetics.5,8,9

Q3. What are the initial management strategy and surgical considerations for the plastic surgeon regarding firework injuries to the face?

These injuries require a multidisciplinary team approach, beginning with an initial trauma evaluation. Once stabilized, diagnostic imaging including a computed tomography (CT) maxillofacial scan to thoroughly evaluate for facial injuries should be obtained. In the event an explosive remains in the body, hospital policy and local authorities should be consulted to ensure the safety of the patient and entire medical staff.

The patient will require appropriate risk stratification prior to proceeding with reconstruction. In the operating room, the primary treatment goals include hemorrhage control, thorough wound debridement, and bony stabilization.9,10 Bony fragments with soft tissue (ie, periosteum) attachments should be preserved, as the face has a reliable blood supply and even small fragments can maintain perfusion.9 Reconstruction with autologous bone grafts, cellular bone allografts, and/or spanning plates may be required when large bony defects are encountered.

When addressing mandibular fractures, an algorithm based on occlusion, stability, and fracture laterality can guide management, ranging from observation to mandibulomaxillary fixation (MMF) to open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) with load-sharing (eg, miniplates, fracture/locking plates) or load-bearing (eg, reconstruction plate) fixation.8 A reconstruction plate provides the most reliable stabilization in comminuted mandible fractures.9

Early stabilization of the facial skeleton is vital, as soft tissue collapse and fibrosis are difficult to correct secondarily.9 Adequate soft tissue coverage should be confirmed prior to bony fixation. Once the bony skeleton is stabilized, soft tissue repair can be performed. In cases with significant bony instability or inadequate soft tissue coverage, an external fixator (eg, ex-fix) can be placed for temporary stabilization. In patients with complex facial trauma, multiple surgeries are often required to reconstruct the bony skeleton and close the soft tissue. The goals of reconstruction are to both restore facial function and facial aesthetics.

Q4. What are the major causes of early and long-term morbidity following facial reconstruction from firework injuries?

Early morbidity is associated with the degree of acute facial trauma; therefore, repeat evaluations are necessary to identify injuries that may have initially been missed due to other distracting findings. Airway precautions are necessary for patients who remain in mandibulomaxillary fixation or with significant nasal trauma. Vision should be reassessed in patients with orbital fractures, especially in those patients who remain sedated.

Injuries to the facial and trigeminal nerves may cause facial weakness or numbness. If not promptly identified, restoration of nerve function may be unlikely.

Infection risk can arise secondary to soft tissue injury as well as contaminated explosive fragments. Additionally, good oral hygiene is paramount for wounds with any intraoral communication.

Bony malunion or misalignment may lead to significant morbidity. Occlusion should be assessed for fractures of the maxilla and/or mandible. Traumatic loss of dentition may destabilize the mandible, leading to atrophy and occlusive malalignment. Oral competence and a swallow assessment may be required prior to starting a diet; patients may require physical rehabilitation to reestablish premorbid mastication. Fractures affecting the condylar joint may lead to temporomandibular joint disease or ankylosis.

Soft tissue contractures can deform normal anatomy and cause several aesthetic and functional deficits. Perioral contractures may affect the ability to phonate or masticate. Injuries to salivary ducts or glands may cause the formation of a ranula, as seen in the patient presented here.

A prospective multicenter cohort study of trauma patients with facial injuries found that 36% experienced a functional limitation and 17% developed posttraumatic stress disorder.11 Further, 34% reported the scars bothered them, and nearly 50% experienced emotional difficulty dealing with the injury.11 Given these medical and psychological complications, long-term follow-up is vital. Early connection with psychiatric and/or counseling services is especially appropriate for patients with significant changes to their functional status or appearance.

Summary

Firework injuries are a frequent cause of accidental trauma to the face. These injuries require careful management to restore facial function and aesthetics. This unique presentation of facial trauma in which the patient had an explosive lodged in his mandible highlights the complex management required for facial injuries caused by fireworks. Multidisciplinary care can ensure patient safety during initial trauma stabilization and patient satisfaction during subsequent reconstruction of such traumas.

Acknowledgments

Affiliations: 1Division of Plastic, Maxillofacial, and Oral Surgery, Department of Surgery, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina; 2Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky; 3Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, The Brody School of Medicine, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina; 4Department of Internal Medicine, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Illinois

Correspondence: Milind D Kachare, MD; Milind.Kachare@louisville.edu

Ethics: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and accompanying images.

Disclosures: The authors report no known or perceived conflicts of interest regarding the material presented in this manuscript.

References

1. Commission USCPS. 2020 Fireworks Annual Report: Fireworks-Related Deaths, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries, and Enforcement Activities During 2020. https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/2020-Fireworks-Annual-Report.pdf?ZSdvk_ep9au0QsqrAgL8S8_tA2LnAT7X

2. Puri V, Mahendru S, Rana R, Deshpande M. Firework injuries: a ten-year study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. Sep 2009;62(9):1103-1111. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2007.12.080

3. Wang C, Zhao R, Du WL, Ning FG, Zhang GA. Firework injuries at a major trauma and burn center: A five-year prospective study. Burns. Mar 2014;40(2):305-310. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2013.06.007

4. Moore JX, McGwin G Jr, Griffin RL. The epidemiology of firework-related injuries in the United States: 2000-2010. Injury. 2014;45(11):1704-1709. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2014.06.024

5. Tadisina KK, Abcarian A, Omi E. Facial firework injury: a case series. West J Emerg Med. Jul 2014;15(4):387-393. doi:10.5811/westjem.2014.1.19857

6. Morris LM, Kellman RM. Complications in facial trauma. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. Nov 2013;21(4):605-617. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2013.07.005

7. Shuker ST. Maxillofacial blast injuries. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. Apr 1995;23(2):91-98. doi:10.1016/s1010-5182(05)80454-8

8. Koshy JC, Feldman EM, Chike-Obi CJ, Bullocks JM. Pearls of mandibular trauma management. Semin Plast Surg. Nov 2010;24(4):357-374. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1269765

9. Girish Kumar N, Vijaya N, Jha AK. Blast injuries of mandible: a protocol for primary management. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. Jun 2012;11(2):191-194. doi:10.1007/s12663-011-0293-y

10. Crecelius C. Soft tissue trauma. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. Mar 2013;21(1):49-60. doi:10.1016/j.cxom.2012.12.011

11. McCarty JC, Herrera-Escobar JP, Gadkaree SK, et al. Long-term functional outcomes of trauma patients with facial injuries. J Craniofac Surg. Nov-Dec 01 2021;32(8):2584-2587. doi:10.1097/SCS.0000000000007818