The Use of Commercial Health Video Games to Promote Physical Activity in Older Adults

Introduction

Over the past 18 months, sales of the Nintendo Wii™, Electronic Arts Sports Active™, and Konami’s Dance Dance Revolution (DDR)™ totaled $2 billion worldwide.1 Gamers today represent a broad range of ages and backgrounds. The average gamer is 39 years old, 40% are women, and more than 25% are age 50 and over.2 It was estimated that by the end of 2009, 68% of American households would have a gaming console in the home.2

Older persons have not missed out on this trend, with several media reports of entire nursing home chains and senior centers purchasing gaming systems and offering games as a part of their programming. Game developers have also expanded their demographics by focusing on developing and marketing games with greater appeal to the general public. Over 84% of the games available on the market today are labeled “E,” meaning they are appropriate for everyone, and these “E” games accounted for the largest market share of all games sold in 2008.2

Why the surge in interest and participation in video games by older adults? One major reason is the fun factor. Innovative technologies such as motion sensors and smart homes have been developed to facilitate healthy aging or aging in place, but these technologies are not interactive or engaging. Virtual reality and spatial 3D user interfaces have been utilized as effective adjuncts to or components of rehabilitation for the past 20 years, but until recently these technologies were quite expensive and not portable. Through recent technological innovations, off-the-shelf gaming consoles can replicate several aspects of a costly virtual reality system, and these systems can be played in an individual’s home.

The combination of improved technology, cheaper price, and age-appropriate games has captured the interest of older adults. These games offer fun and convenient activities that are cross-generational, social, and could have health benefits. Commercially available health games have the potential to be a health promotion intervention to increase an older adult’s physical activity levels; however, these types of games have only been available since 2007, and several questions remain unanswered about the efficacy, feasibility, and safety of these games for older persons. The purpose of this review article is to provide an overview of the commercial health video games available that could promote physical activity, review the research being done with these games, and discuss future directions.

A Brief History of Health Video Games

The video game industry began in the mid-1970s with the advent of the video arcade. During the 1980s and 1990s, the technology and graphics improved, prices dropped, and video games effectively moved out of the arcade and into the home. Few individuals purchased the first home games with their large and expensive consoles and rudimentary graphics. Games from that period through today typically consisted of a console connected to a television or computer to display the game and a controller that the player manipulated to interact with the game. Some would say that the technology may have evolved too much during this period, as the games and controllers became quite complicated, and market share was lost due to lack of interest from the general public.3

The current generation of games and gamers are quite different. The games incorporate advanced technologies, but they couple those technologies with relatively simple user interfaces and easy-to-manipulate controllers. Gamers now can use their entire body to play the games developed for the Sony PlayStation® 2 EyeToy™, perfect a real yoga move using Wii Fit, or manipulate real physical props like guitars and drums to play Guitar Hero®.

The gaming industry has evolved as well, with entirely new areas of research and development in “Health Games” to best meet the demands of the ever growing market. Health games are specifically designed to encourage the participant to engage in healthful behaviors.4 This may be physical activity (Wii or Dancetown Fitness System®), improving eating habits, stopping smoking, or even engaging in a virtual world in which recovering substance abusers can practice and reinforce relapse-prevention skills.

The health video gaming industry has expanded significantly over the past few years and is supported by several foundations looking to develop better health promotion dissemination vehicles. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has funded 20 researchers during the past two years to pursue studies developing or modifying health games to improve physical activity or some aspect of self-care. Senior-specific topics include: “Commercially Available Interactive Video Games for Individuals with Chronic Mobility and Balance Deficits Post-Stroke” at the University of South Carolina; “Seniors Cyber-Cycling with a Virtual Team: Effects on Exercise Behavior, Neuropsychological Function and Physiological Outcomes” at Union College Department of Psychology; and “Action Video Games to Improve Everyday Cognitive Function in Older Adults” at the University of Florida.4

Current and Future Research

The research in this area is in the early stages. This new generation of technology has the potential to effectively facilitate increasing physical activity or other behavioral changes; however, published studies to date have been done only in children and adolescents.5-8 Currently, no published research addresses the effect of these gaming systems on energy expenditure, behavioral change, or health benefits in older adults. In general, children and adolescents who engage in interactive video games expend more energy than playing more traditional video games,5, 6 but the amount of expenditure is typically less as compared to playing the actual game.5,7 Researchers have also reported that with certain games, as skill level increases, so does the energy expenditure.7 No studies have been published in the pediatric or geriatric literature on the effect of playing these games on physical or functional performance in healthy individuals. In the rehabilitation literature, there has been one case study of an adolescent with cerebral palsy who incorporated Wii as part of his rehabilitation intervention with positive results.9

Health Video Games for Older Adults

The three most popular health video games that have the potential to be appropriate for seniors and incorporate physical activity are Dancetown, EyeToy, and Nintendo Wii. There are no publications to date that assess relationships between older adults playing these games and levels of physical activity.

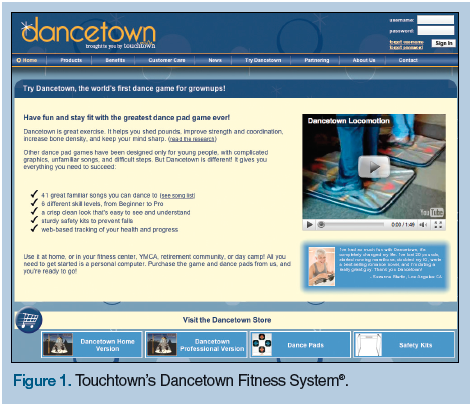

Dancetown Fitness System®

The only game designed specifically for seniors is Touchtown’s Dancetown Fitness System® (Figure 1), the more “mature” version of DDR.10 This gaming system utilizes a dancepad marked with directional arrows. The pad is connected to a personal computer that drives a display device (a television or a computer screen). When the player is ready, graphics appear on the screen to guide the dance step movements. At first, movements are slow, but progress in speed and complexity as the player becomes more skilled.

Whereas DDR features quick steps to rock and roll and hip hop, Dancetown incorporates a more senior-friendly design, slower dance steps, and safety features like grab bars. An additional innovative feature of Dancetown is the incorporation of validated, senior-specific assessment tools such as the Senior Fitness Test, The Timed Up and Go, the Tinetti Balance and Gait Test, and the Six-Minute Walk Test.

Dancetown records performance and generates results that could be utilized by a physical therapist or a physician.10 To date, there are no published studies on Dancetown, although a few have been published studying DDR as a potential intervention to increase physical activity in children.5-8,11 These studies suggest that children age 8-10 years will increase total weekly physical activity and decrease sedentary activity time when they have access to DDR.8,11 One other study compared energy expenditure of adolescents playing DDR, Wii, and walking at 5.7 miles per hour, and determined that playing DDR was the equivalent of moderate-intensity walking.5The authors concluded that DDR played at the appropriate level could be an effective intervention to promote physical activity in children. The findings from this research could be applied to older adults who may enjoy participating in this type of activity in their home or at a senior facility.

The Sony PlayStation® 2 EyeToy™

The EyeToy (Figure 2) is a low-cost, off-the-shelf, video-capture system. It consists of a camera connected to the PlayStation 2 gaming system, which is connected to a television. To interact with the system, the camera is turned on, and an image of the player appears on the screen. The system works best if the individual is alone in a well-lit room so that the character on the screen is clearly delineated.12 When the player moves his/her body, the image on the screen mirrors the actual movements. Players move their bodies to “play” different virtual games, such as popping bubbles, painting a rainbow, or even completing a do-it-yourself project. Sony has plans to release the next version of the EyeToy in the PlayStation Move game to be released in Fall 2010. The PlayStation Move is Sony’s response to the Wii and has the potential to be easier to manipulate and provide better feedback to older adult players.13

Three articles have been published assessing whether the EyeToy is a feasible and effective adjunct to rehabilitation post-stroke.13-15 Yavuzer et al13 compared Functional Independence Measure (FIM) scores among 20 patients with hemiparesis who added 30 minutes of EyeToy play to conventional therapy to a control group receiving conventional therapy and a placebo treatment. The intervention group demonstrated significant improvements in FIM scores as compared to controls. Researchers reported that participants had high adherence rates and enjoyed the activity.

A feasibility study was conducted to determine whether an older adult post-stroke could successfully interact with the user interface and to identify appropriate games for seniors.14 A 76-year-old woman, 17 months post-stroke, independently played with the EyeToy for 20 one-hour sessions distributed over four and a half weeks. The EyeToy sessions were not supervised, although the patient’s companion was present for each session. Researchers reported that the subject enjoyed playing the games but found that several games were either too difficult or just not interesting to the subject. However, five of the 15 games were played repeatedly by the subject. Researchers reported that after the initial orientation, the subject could independently set up and play the system. After the intervention period, the subject demonstrated significant improvements on the Dynamic Gait Index, as well as trends toward improvements on several balance measures. The subject reported that she would continue to play after the study period.14

Rand et al15 investigated the feasibility of the EyeToy as compared to the IREX® Virtual Reality Exercise system as an intervention for healthy older adults and those with disability. Results from the study indicate that the EyeToy was a feasible intervention for individuals with acute and chronic stroke, it was suitable and easy to operate for older adults, and older adults enjoyed interacting with the EyeToy as much as younger adults, but they enjoyed playing different games.

Preliminary research indicates that the EyeToy may be an effective intervention to increase physical activity and improve physical fitness in healthy older adults. Lotan and colleagues16 reported that middle-aged adults (mean age, 52.3 ± 5.8 yr) did improve on measures of physical fitness after playing the EyeToy for two 30-minute sessions per week for six weeks. The EyeToy appears to be a feasible option for healthy older adults and those with impairments. The user interface is simple, and older persons have reported that the games are enjoyable.14,15 Adherence rates for studies have been high, and this is especially important for those individuals recovering from stroke or other impairments. Adherence rates to home exercise programs are traditionally low. If the EyeToy can improve those rates and improve physical function, then it follows that physical activity levels may increase.

Nintendo Wii™

The Wii gaming system was released by Nintendo in November 2006. The name “Wii” was chosen to emphasize the “we” aspect of the game, meaning that it is meant for everyone to play.16 According to Nintendo and the popular press, older persons have embraced Wii. Nintendo has specifically included seniors in a broad-based marketing campaign launched in 2006,16 and there have been reports of people in their 90s and 100s playing the game.17 In 2007, Erickson Living partnered with Nintendo to host a series of Wii Bowling Championships across the nation. Seniors created teams at their local assisted living facilities and participated in a “virtual bowling championship” with other teams across the nation. Highlights of the competition were posted on www.youtube.com, creating much positive press for the gaming system. Shortly after the first championship, several newspapers and websites reported about the surge in nursing homes and senior centers purchasing Wiis.

The original Wii includes a “Wiimote,” the primary remote controller for the console. The controller is a handheld device with a few buttons that allows users to navigate the games. It has an accelerometer and utilizes infrared technology that tracks and translates real motion into the virtual game, allowing players to swing a virtual tennis racquet or golf club. Players receive feedback about performance through their “Mii,” or virtual self. When players first interact with the game, they create a Mii, which appears on the screen to translate a player’s real motions into virtual motions and track performance.16

The Wii Fit (Figure 3) was the first interactive video game incorporating a balance board designed specifically for the Wii system. The Fit was released in December 2007 and has become the second best selling video game in history. The balance board is able to calculate body mass index, track center-of-pressure movements, and provide feedback on performance. By including a performance tracking and education component, Wii Fit shifts away from playing games and toward an innovative health and fitness focus. When players first interact with Wii Fit they complete several balance tests conducted by the game. Based on the game’s assessment of performance, the system calculates a “Wii Fit Age,” which can be a player’s actual age, or significantly younger or older. The system tracks time between sessions, weight lost/gained, and overall performance. The system will reassess balance performance at specified times and generate graphs for a visual display of progress. It also allows users to track physical activities outside of the game. Wii Fit includes a “virtual trainer” who demonstrates the strength and yoga exercises, provides feedback on performance, and educates users about the importance of posture, strength, and balance. The Fit offers four categories of games: balance, strength, yoga, and aerobic. As users progress, exercises are “unlocked,” for a total of 47 activities.17

Criticisms about Wii Fit include that it is limited in providing a “real workout.”18 Each exercise lasts approximately one to two minutes, and there is a break while users choose the next exercise. In 30-45 minutes of Wii time, a user may engage in only 20 minutes of actual physical activity or exercise.

The next generation of health video games is already lining up to remedy this problem. Electronic Arts released Sports Active in May 2009. It is an interactive workout DVD that uses Wii and Wii Fit to lead a participant through 30-45 minutes of physical activity. Sports Active also does brief “health assessment” questionnaires that allow players to track their sleep habits, eating habits, and how much water they have drunk that day. Nintendo is also developing new games, and in June 2009 announced it would include technology to monitor such vital signs as heart rate and oxygen levels in the next generation of Wii.

Although more popular than the EyeToy, less published research exists on Wii and Wii Fit. Early publications focused on injuries associated with younger people playing Wii. There were several reports of adolescents and young adults with wrist and shoulder injuries due to too much play19, 20 or becoming too involved in the game and losing awareness of the environment, resulting in fractures and falls.21,22,23,24

The most recent reports have focused on assessing the energy expenditure associated with playing the various Wii games. In Wii Sports Pack, boxing appears to have the highest energy expenditure for children and adults.5,25,26 The most popular game with seniors is bowling; however, bowling has been shown to have the smallest increase in energy expenditure of all the Wii Sport Games.5 In addition, the bowling game can be played while sitting, which makes it a great social opportunity; however, it may not have the health benefits of a standing game.

Over the coming year, more will be understood about the role of Wii to increase physical activity or as an adjunct to therapy. A few case reports presented in early 2009 supported the assertion that Wii might facilitate the achievement of certain physical therapy goals.28,29 One case presented an 89-year-old woman who played the bowling game standing as a component of therapy.28 The authors reported improvements in balance and balance confidence. Another study assessed the effect of Wii and Wii Fit as an adjunct to traditional therapy with a 69-year-old woman with balance impairments.29 Outcomes suggest that including Wii and Wii Fit as part of therapy may have contributed to the patient’s compliance with therapy and improved performance on balance and coordination assessments.

There is much interest in determining whether playing Wii can improve function and mobility in patients with movement disorders. The National Institutes of Health has funded two studies using Wii. Researchers at Vanderbilt University are assessing movement data collected from the Wiimote.30 Their purpose is to determine whether the Wiimote produces reliable and valid data to study individuals with movement disorders. Researchers at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto are examining the effectiveness of Wii gaming versus recreational activity in patients receiving standard rehabilitation after stroke.27 Other funded studies include a pilot study assessing the effect of playing Wii on movement and depression in individuals with Parkinson’s disease at the Medical College of Georgia,28 and the effects of Wii Fit on strength and balance in healthy older adults at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland.29

Of the three most accessible and popular health video games for seniors, Wii has generated the greatest popular interest. It has senior-appropriate options, and older persons need to be educated on how to play the games to get the greatest health benefits. If they are sitting and bowling, they will probably not be improving balance and strength, but they may be socially engaged. Social engagement is an important and meaningful activity, even if it is not actually physical activity. However, if they are patients who are recovering from strokes or diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, then Wii games played sitting or standing may be an option to improve range of motion and mobility.

Wii Fit poses the greatest questions. The Fit board is quite narrow, 20 inches wide by 12 inches long and 2 inches high, and does pose a fall risk, especially for an older adult with slower reaction times and difficulty with dual tasks. In addition, the games can be quite challenging, and several are not appropriate for older adults with physical or cognitive impairments. Informal queries with staff at senior centers and assisted living facilities indicate that older adults can lose their balance while playing Wii Fit and are always supervised. Finally, Wii Fit does provide feedback on performance, but often that feedback can be discouraging. If an individual does not perform well, the virtual trainer or the Mii looks sad and disappointed. This is not the feedback one would want a new exerciser to have, and may impede behavioral change.

Our Research

Our own research addresses aspects of how video gaming technology can be appropriately modified to appeal to older persons and be utilized as an effective health promotion intervention. One question not yet addressed in the literature is that of user interface and usability. Although Nintendo has made great efforts at simplifying the console to improve the access and usability of Wii, there are no data supporting that seniors can easily navigate the system. Discussion from a presentation entitled “The Use of the Wii and Related Technology in Physical Therapy” at the American Physical Therapy Association’s Combined Sections Meeting in February 2009 indicated that therapists typically set up the games instead of the patients. Discussions with staff at several senior facilities support that activity directors or technicians set up the systems for older adults to play.

We have conducted several focus groups composed of both senior Wii veterans and novices to assess user interface design and feasibility, and with physical therapists using the Wii as part of therapy with geriatric patients. Results from focus groups indicate that seniors are very interested in playing the Wii, especially if there is a particular health benefit that can be achieved with play.30 However, both older adults and therapists report that several of the games are too fast for older adults, and the feedback too negative.30,31 One researcher studied a group of older adults learning to play Wii bowling and reported several issues with the ability to press and release the correct button at the correct time in order to successfully play the game.32 These results all support the need to develop senior-appropriate fun games, and suggest that this may be a potential venue to deliver health promotion interventions.

Our current research is focused on modifying current gaming technologies to develop a senior-friendly video game. This game could be played in any setting—the home, gym, or senior center—and could potentially deliver programming to improve strength or balance to be used as an adjunct to traditional physical therapy. We are borrowing several concepts currently incorporated in gaming consoles to see if we can make the intervention fun and engaging to improve adherence. If successful, this format may be a safe, reliable, and valid way to increase physical activity among seniors.

Conclusions

Gaming, and in particular, “exergames,” has captured the public’s attention and will continue to grow as a part of our culture. While these games show great promise as an introduction to physical activity, the virtual game still has a long way to go before replacing actual activity. Few of these games are tailored for older adults, and some games may put an older adult at increased risk of a fall. However, adherence rates for games appears to be high, which supports the possibility of health video games as an effective intervention to promote physical activity in older adults. The EyeToy and Dancetown are probably better options for older persons at this time due to ease of use, functionality of games, and specificity to the geriatric population.

That being said, health video gaming has great potential for both healthy older adults and those with impairments. As the games are modified to increase their appeal and appropriateness for older adults, and as researchers determine what participating in these games translates to for function and mobility, we may see health video games as an effective and safe venue to increase physical activity in a fun and meaningful way for older adults.

Acknowledgment

This project was supported by the “Bringing Basic Scientist to Aging” pilot grants program through the University of North Carolina Institute of Aging. Funding for this grant program was provided by The UNC-CH Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Economic Development. The author reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Shubert is a Research Scientist, The University of North Carolina Institute on Aging, and Adjunct Assistant Professor, The UNC Division of Physical Therapy, Chapel Hill.

References

1. Gaudiosi J. Health games become serious business. www.reuters.com. Accessed March 15, 2010.

2. Essential Facts About the Computer and Video Game Industry. Entertainment Software Association; 2008. Accessed March 15, 2010.

3. LaViola JJ, Jr. Bringing VR and spatial 3D interaction to the masses through video games. IEEE Comput Graph Appl 2008;28:10-15.

4. Health Games Research: Advancing the effectiveness of interactive games for health. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. https://www.healthgamesresearch.org. Accessed March 15, 2010.

5. Graf DL, Pratt LV, Hester CN, Short KR. Playing Active Video Games Increases Energy Expenditure in Children. Pediatrics 2009;124(2):534-540.

6. Lanningham-Foster L, Jensen TB, Foster RC, et al. Energy expenditure of sedentary screen time compared with active screen time for children. Pediatrics 2006;118:e1831-1835. Published Online: December 1, 2006.

7. Sell K, Lillie T, Taylor J. Energy expenditure during physically interactive video game playing in male college students with different playing experience. J Am Coll Health 2008;56:505-511.

8. Maloney AE, Bethea TC, Kelsey KS, et al. A pilot of a video game (DDR) to promote physical activity and decrease sedentary screen time. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:2074-2080.

9. Deutsch JE, Borbely M, Filler J, et al. Use of a low-cost, commercially available gaming console (Wii) for rehabilitation of an adolescent with cerebral palsy. Phys Ther 2008;88:1196-1207. Published Online: August 8, 2008.

10. What is Dancetown? Cobalt Flux Inc. Accessed March 15, 2010.

11. Murphy EC, Carson L, Neal W, et al. Effects of an exercise intervention using Dance Dance Revolution on endothelial function and other risk factors in overweight children. Int J Pediatr Obes 2009:1-10.

12. Eye Toy® USB Camera. Play Station. https://www.us.playstation.com/ps2/accessories.97036.html. Accessed March 15, 2010.

13. Yavuzer G, Senel A, Atay MB, Stam HJ. “Playstation eyetoy games” improve upper extremity-related motor functioning in subacute stroke: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2008;44:237-244. Published Online: May 10, 2008.

14. Flynn S, Palma P, Bender A. Feasibility of using the Sony PlayStation 2 gaming platform for an individual poststroke: A case report. J Neurol Phys Ther 2007;31:180-189.

15. Rand D, Kizony R, Weiss PT. The Sony PlayStation II EyeToy: Low-cost virtual reality for use in rehabilitation. J Neurol Phys Ther 2008;32:155-163.

16. Lotan M, Yalon-Chamovitz S, Weiss PL. Improving physical fitness of individuals with intellectual and developmental disability through a Virtual Reality Intervention Program. Res Dev Disabil 2009;30:229-239. Published Online: May 13, 2008.

17. Wii. Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wii. Accessed March 15, 2010.

18. Parker A. OAPs say nurse, I need a Wii. The Sun. September 14, 2007. Accessed March 15, 2010.

19. Wii fit. Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wii_Fit. Accessed March 15, 2010.

20. Sparks D, Chase D, Coughlin L. Wii have a problem: A review of self-reported Wii related injuries. Inform Prim Care 2009;17:55-57. Published Online: March 14, 2008.

21. Robinson RJ, Barron DA, Grainger AJ, Venkatesh R. Wii knee. Emerg Radiol 2008;15:255-257.

22. Bhangu A, Lwin M, Dias R. Wimbledon or bust: Nintendo Wii related rupture of the extensor pollicis longus tendon. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2009;34:399-400.

23. Peek AC, Ibrahim T, Abunasra H, et al. White-out from a Wii: Traumatic haemothorax sustained playing Nintendo Wii. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2008;90:W9-W10.

24. Harrison M. No Wii cause for concern. Emerg Med J 2009;26:150.

25. Rajani R, Kumar A, Jiwani M. Wii seems safe with pacemakers. BMJ 2008;337:a3103.

26. Graves LE, Ridgers ND, Stratton G. The contribution of upper limb and total body movement to adolescents’ energy expenditure whilst playing Nintendo Wii. Eur J Appl Physiol 2008;104:617-623. Published Online: July 8, 2008.

27. Graves L, Stratton G, Ridgers ND, Cable NT. Energy expenditure in adolescents playing new generation computer games. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:592-594.

28. Clark RH, Kraemer T. Clinical use of Nintendo Wii bowling simulation to decrease fall risk in an elderly nursing home patient: A case report. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2008;32(4):174.

29. Nichols B. Case review: Use of the Nintendo Wii Fit and outdoor challenge for rehabilitation of an elderly female patient with age-related balance impairments. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2009;33(3):123.

30. WiiMote. Game Controller as a device to study movement disorders. U.S. National Institutes of Health. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00802191. Updated December 2, 2008. Accessed March 15, 2010.

31. Effectiveness of virtual reality exercises in STroke Rehabilitation (EVREST). Clinical Trials. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00692523. Updated October 1, 2009. Accessed March 15, 2010.

32. Hinley P. Wii-Hab may enhance Parkinson's treatment. Medical College of Georgia News. June 11, 2009. Accessed March 15, 2010.

33. Elderly wanted for Wii experiment. BBC News. https://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/scotland/north_east/7869445.stm. Updated February 5, 2009. Accessed March 15, 2010.