The Effectiveness of an Environmental and Behavioral Approach to Treating Behavior Problems

Author Affiliations: Dr. Huh is Associate Director of Education and Evaluation at the VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center; Dr. Areán is Associate Professor, Dr. Bornfeld is Staff Psychologist, and Dr. Elite-Marcandonatou is Staff Therapist at the Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction and Background

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is considered the second most prevalent dementia after Alzheimer’s disease (AD), comprising 15-25% of all dementias.1-3 Core features include dementia, fluctuating consciousness, hallucinations, paranoid delusions, parkinsonism, and neuroleptic sensitivities.2,3 Hallucinations and delusions have been the most diagnostically specific neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) distinguishing DLB from AD.4,5 A recent study indicated significant levels of aggressive behaviors on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) in patients with DLB,5 with rates similar to that of patients with AD.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with DLB are very upsetting to family and facility caregivers.6,7 NPS leads to poor quality of life for patients and caregivers and contributes to psychiatric morbidity in caregivers if they do not feel effective in managing these symptoms.8 Therefore, finding effective techniques for managing NPS in patients with DLB is a critical goal for clinicians and families.

Managing DLB-related symptoms is complicated.9 Neuroleptic medications are most commonly used to manage agitated behaviors in dementia. However, these medications tend to be less effective in general,10-12 and in patients with DLB are particularly concerning because of their sensitivities to these medications.3,13,14 Behavioral strategies are a viable alternative to medication management.15-18 Successful models combine a behavioral approach, medical consultation, and family involvement. A number of reports suggest that of all the interventions available, behavioral models may be the best available treatments for agitation in patients with general dementia.19 Interestingly, there are no studies or reports that examined these behavioral approaches to address disruptive behaviors in DLB. Symptoms in DLB differ from AD and, therefore, treatment approaches may require further modifications to accommodate these differences.

The purpose of this case study is to provide a descriptive report for professionals caring for persons with DLB and to highlight the need for more evidence-based interventions for treating DLB-related problem behaviors.

_________________________________________________

Case Presentation

DG, a 79-year-old Filipina woman with DLB, was referred to the Senior Behavioral Health Services (SBHS) program in December 2005. DG was placed in a board-and-care facility in April 2005, her second long-term assisted living facility, and the primary site for implementing the intervention. Facility staff referred her for the following behaviors: hitting and kicking, unpredictable yelling, cursing, banging the walls, and hallucinations. Staff also reported feeling intimidated by her persistent “frown.” These behaviors had been present since her admission to this facility and had been problems in her previous facility. DG’s daughter, RM, her primary family caregiver, expressed concerns that the staff would not be able to care for DG compassionately as a result of her difficult behaviors, which contributed to tension between the family and staff.

DG had initially presented with behavioral problems in 2000, which included difficulties with activities of daily living (ADLs), dressing in a disorganized fashion, hearing voices, wandering, and hoarding. After a failed trial of donepezil and risperidone, she was referred to a dementia clinic. She was found to have parkinsonism, dementia, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and recurrent urinary tract infection (UTI). A computed tomography (CT) scan performed in 2003 indicated mild atrophy, more prominent in the frontotemporal regions, with scattered areas of reduced density consistent with small-vessel ischemic changes. There was no observable basal ganglia pathology at this time. These findings led to a diagnosis of DLB. Medications at the time included ciprofloxacin, acetaminophen, risedronate, trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole, bisacodyl, docusate sodium, and quetiapine.

_________________________________________________

Intervention: The Collaborative and Multicomponent Approach

The SBHS was a demonstration project funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The goal of the SBHS project was to develop and disseminate evidence-based treatments of depression and agitation into long-term care facilities. The SBHS collaborated with 10 facilities throughout the San Francisco Bay area. These facilities ranged in size (from 8 to 56 beds) and had staff with varying educational backgrounds (from < 5 years to masters-level nurses and occupational therapists). The SBHS project was developed based on the chronic disease management model.20

This model includes several components:

1. Provider training in the recognition and management of dementia and accompanying NPS which included five training modules and a follow-up training session provided in a group format once a week

2. Consumer and family education about NPS

3. Improved coordination of care through: (a) assessment, (b) treatment tracking and monitoring of patient outcomes to the intervention, and (c) involving professional caregiving staff and family in the development and application of the intervention

4. Better access to specialty services and collaboration between specialty care and primary care

A care manager is a critical component of this model. The care manager provides training to staff, coordinates and provides assessments and treatments, facilitates family-staff-provider communication, monitors patient progress, and serves as a consultant. The care managers in the project included two licensed clinical social workers, one marriage and family therapist, and three clinical psychologists. DG’s care manager was a licensed social worker with more than four years of interventions experience with children and adults.

Assessment of the Case Patient

The care manager conducted a baseline assessment, using the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) to determine cognitive status21; the Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living (Katz ADL) to assess DG’s ability to perform everyday tasks, such as dressing, toileting, and feeding22; and the CMAI to identify discreet categories of agitated behaviors and assess their frequency and intensity.23 The CMAI was the primary outcome measure. In addition to these functional measures, the care manager also assessed for potential triggers and consequences to DG’s disruptive behavior, using the Motivation Assessment Scale (MAS).24 She also completed the Reinforcer Assessment for Individuals with Severe Disabilities (RAISD) to identify pleasurable activities and objects, which she used in the intervention.25 Finally, she completed the Pleasant Event Schedule (PES) to identify objects/activities for reinforcement of appropriate behaviors in the individualized intervention plan.26 These measures were completed every 2 weeks for 32 weeks. All measures were used as clinical as well as empirical tools to assess and monitor behavior changes and may be suitable for use in many different clinical settings. The care manager found little difficulty in working with the professional staff or patients while conducting the assessments.

The care manager became the central liaison for all providers involved in the patient’s care, including primary care, psychiatrists, adult day health programs, and family members. However, the following sections will provide reports of her interactions primarily with DG, RM, and facility staff.

Results of Assessment

DG demonstrated severe impairment on the MMSE (0 out of 30). She was able to identify common objects in her room (eg, chair) and items in a coloring book (eg, cat). The care manager also assessed typical day-to-day memory, and on most sessions DG indicated memory for the name of her primary professional caregiver and the care manager. However, she was often not oriented to date, time, and place.

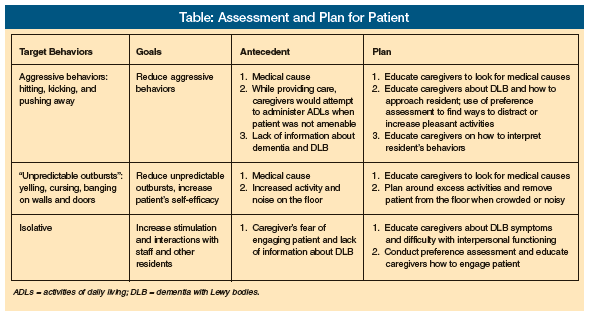

The CMAI identified the following target behaviors: hoarding, hitting, making strange noises and/or pushing away caregivers and previously described yelling, cursing, banging the walls and doors, and hallucinations. The MAS found that triggers to hitting, kicking, and pushing away included: (1) attempts to help DG with ADLs; (2) UTIs; and (3) excess noise and activity on the floor. Caregivers reported decreasing their activities with DG because they believed that her symptom of masked faces (ie, flat affect, “furrowed” facial expression) indicated displeasure or anger. As a result, DG was left largely alone and understimulated (see Table for presentation of target behaviors and antecedents).

Intervention Plan

The care manager developed a clinical plan based on the cognitive, behavioral, and environmental assessment (Table). An essential aspect of DG’s care plan involved psychoeducation about DLB for her daughter, RM, and residential staff. For example, it was important to teach the staff that DG’s cognitive status may fluctuate daily because of her DLB. In addition, staff were taught that DLB affected DG’s ability to interpret and respond to social situations appropriately, such as her persistent frown. Caregivers were instructed about using DG’s behavioral cues to determine optimal times to engage her in dressing, brushing teeth, and bathing. For example, when DG raised her hand, this indicated that she was not ready for them to approach. Instead, the caregivers were taught to return later, and inform her that they were there to help her with an activity.

Caregivers learned to adjust their expectations that DG “actively” engage in activities and to broaden their understanding about the different ways in which people communicate and participate. For example, DG communicated through her behaviors that instead of actively coloring, she preferred to simply watch those around her color and draw, which could be considered a form of participation. When DG seemed to refuse an activity by shaking her head, pushing caregivers away, or deeper furrowing of her brow, DG was communicating her desire to just observe. Finally, staff members were taught how to assess and manage DG’s symptoms and to monitor for any medical problems that could exacerbate the symptoms (eg, UTI, dehydration, sleep deprivation, pain).

To increase DG’s activities, caregivers were educated that her flat/angry affect did not always indicate displeasure but was related to her parkinsonism from DLB, and to continue to engage her in activities despite her flat affect. Caregivers began to use this new knowledge about DLB to adapt their caregiving techniques/approaches to meet DG’s needs. They learned to become more sensitive, observant, patient, and flexible in providing care.

The MAS assessment indicated that DG’s target behaviors of yelling or hitting the door were motivated by her need to escape from noisy or populated situations. Caregivers were taught to ensure that DG had a quiet and calm space, and were able to make continual adjustments in the environment to meet this need. They would either take her for a walk or take her to her room and turn on her favorite music.

The PES and the RAISD suggested that DG enjoyed the following pleasurable activities: gentle balloon-tossing, rolling a ball on the floor for her to kick with her feet, drawing in a coloring book and watching others draw, naming pictures of animals, flowers, and other objects, folding clothes/laundry, writing down familiar names on a piece of paper, listening to soft music, and watching people dance. Caregivers began to introduce these activities as a way to distract or redirect DG when she was resisting care or becoming upset. For instance, while bathing her, they would often sing and dance around her when she became upset.

The care manager assisted with the implementation of care plans by providing updates and feedback to DG’s daughter RM regarding the progress of the intervention and the consultation she provided the staff. RM was provided additional reference and background material about DLB to gain greater understanding of her mother’s symptoms. RM was also educated about how DG’s symptoms might impact her interactions with her caregivers.

Outcome

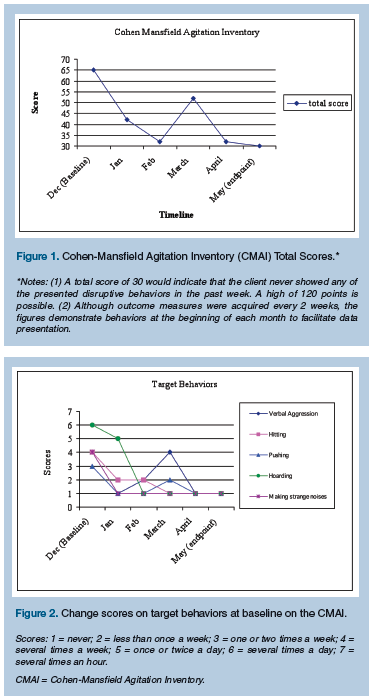

Scores on the CMAI decreased considerably, indicating a significant reduction in her agitated behavior due to the 32-week intervention (Figure 1). DG experienced several fluctuations on measures due to such medical issues as a UTI. On target behaviors, there were significant declines in verbal aggression (baseline = 4, endpoint = 1), hitting (baseline = 4, endpoint = 1), pushing (baseline = 3, endpoint = 1), hoarding (baseline = 6, endpoint = 1), and making strange noises (baseline = 6, endpoint = 1) (Figure 2).

Scores on the CMAI decreased considerably, indicating a significant reduction in her agitated behavior due to the 32-week intervention (Figure 1). DG experienced several fluctuations on measures due to such medical issues as a UTI. On target behaviors, there were significant declines in verbal aggression (baseline = 4, endpoint = 1), hitting (baseline = 4, endpoint = 1), pushing (baseline = 3, endpoint = 1), hoarding (baseline = 6, endpoint = 1), and making strange noises (baseline = 6, endpoint = 1) (Figure 2).

Informally, caregivers reported gaining significant knowledge of dementia, increased self-efficacy in managing DG’s behaviors, and increased pleasure in interacting with DG. Although DG continued to refuse care at times and to experience active hallucinations that caused her to yell, the staff felt more comfortable redirecting her. RM reported significant alleviation of her anxiety about her mother’s hallucinations and behaviors. RM also began to work in a more collaborative manner with the caregivers and felt that she was able to make more informed decisions about DG’s healthcare.

Discussion and Conclusion

Dementia with Lewy bodies leads to significant distress in formal and informal caregivers and is among the most difficult disorders to manage. This case study demonstrates the effectiveness of a collaborative and environmentally-driven approach for addressing agitation in persons with DLB. This approach has been effective for use in assisted living facilities for patients with AD,16 and this case report indicates that the same may be true for patients with DLB. This case shows that a combination of education, assessing the triggers for agitation, and examining the consequences of that behavior can lead to an effective plan to help reduce and manage these troubling behaviors.

Finally, care managers and existing facility staff were quite diverse in their clinical training and indicate that the model used in this project may be suitable for a range of clinical practitioners. DG had demonstrated several aggressive behaviors that caregivers in both of her facilities described as “care-resistant” and “intimidating.” These behaviors contributed to DG’s reduced quality of life due to the difficulty caregivers experienced in interacting with DG. Following implementation of the intervention, DG’s agitated behaviors decreased considerably, and staff reported that management was far easier. This case demonstrates the utility of a tailored, empirically-supported behavioral and environmental approach to addressing difficult behaviors in individuals with DLB.

Acknowledgment This work was supported solely by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration grant H79-SM52236.

The authors report no other relevant financial relationships.