The Effect of the Obama Stimulus Plan on Geriatric Healthcare

Change is coming—in the form of the Stimulus Package, as well as President Obama’s healthcare reform plan. Actually, change is clearly upon us. The elements of this change have been happening slowly over the last several years, of course. Much occurred well before President Obama’s Stimulus Bill, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, was signed into law.

In 1993, key members of Congress led by Senators Max Baucus (D-MT) and Edward Kennedy (D-MA) agreed on four principles that appear to remain as the foundation for our current round of reform. These principles are:

• The healthcare system has to cover every American.

• The health insurance model has to be revamped so that insurers compete based on price and quality, not on who’s better at shedding risk.

• Cost savings have to be realized through using health information technology (IT) and increasing efficiency throughout the system.

• Prevention must be emphasized at every step along the way.

Many of these elements remain today in the President’s plan for healthcare reform. However, the Medicare system has actually been changing and testing different systems to gain control on access, quality, and cost. Of course, the major focus has been, and will continue to be, on cost.

Recently, AARP examined Medicare attempts to cut costs and identified the key findings below. These findings point to a future approach aimed mainly at significant changes to the physician fee schedule, as well as dramatic reductions in Medicare Advantage payments.1

AARP Demonstration of Savings Results for Medicare

Positive Savings:

• Changing the incentives from a cost-based system to episode payment has resulted in measurable and ongoing savings.

• The physician fee schedule can be an effective tool to reduce spending on physician services.

Mixed Results:

• Although bundling fee-for-service (FFS) payments across provider types and competitive bidding show promise for cost containment, this comes with a significant administrative cost.

• Home health agencies responded to the prospective payment system by increasing the efficiency of their operations and shifting their mix of patients.

• Further savings from prevention of fraud and abuse will require investment in IT and more program oversight.

Not Shown to Produce Positive Savings:

• Prospective payment for nursing facilities has not been successful.

• Despite the logic in focused professional support for those with chronic conditions, the Medicare demonstrations have not shown a reduction in costs.

• Medicare Advantage plans, on average, are paid more than FFS Medicare, thus not demonstrating any cost savings.

With all of this change going on, it’s vital that healthcare professionals stay on top of the legislative and regulatory changes that will impact their work. An examination of the Stimulus Package shows four key areas of focus that will impact our work—and perhaps not as one would expect.

Funding for Primary Care Professionals

Despite the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report painting a dire outlook for our geriatric workforce, it appears the situation is not poised for improvement. Currently, commercial payers are reimbursing physicians 10% more than Medicare. For example, the average commercial reimbursement for a new patient visit (99203) is $109.51, while the Medicare reimbursement for the same visit is just $91.03. For existing patient visits (99213), the difference is even greater, with commercial reimbursement at $71.67 and Medicare $59.80.2

While this difference is likely to remain the same—given the proposed Medicare Advantage cuts presented in President Obama’s State of the Union address—overall physician reimbursement is expected to decline for both commercial payers and Medicare.

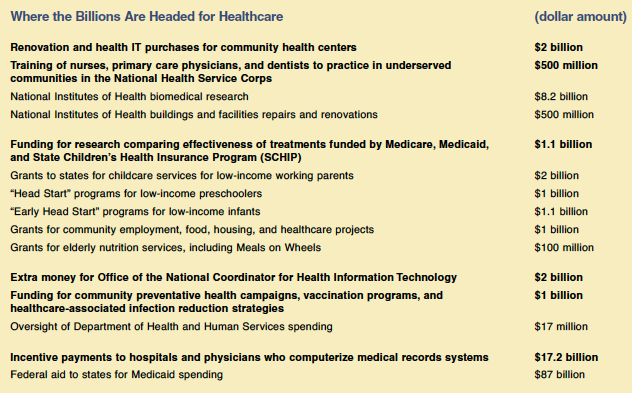

This is at the same time that the Stimulus Package includes $500 million to promote primary care professional development in underserved areas. Specifically, funds are being provided for the training of nurses, primary care physicians, and dentists through the provision of healthcare personnel under the National Health Service Corps program, and for the patient navigator program.

It’s not clear how, if at all, this will improve the provision of geriatric primary care. In addition, with the decrease in reimbursement it appears highly unlikely that, despite the message put forth in the IOM report, we are likely to see an increase in these key provider groups.

Health Information Technology

The Secretary of Health and Human Services will invest in the infrastructure necessary to allow for and promote the electronic exchange and use of health information for each individual in the United States, consistent with the goals outlined in the Strategic Plan developed by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Such investment can be used for the acquisition of hardware or software provided the products are certified to permit the full and accurate electronic exchange and use of health information in a medical record, including standards for security, privacy, and quality improvement functions adopted by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology.

Health Information Technology has been demonstrated to produce potential savings. A recent article in Archives of Internal Medicine showed that clinicians using an electronic prescribing system appeared more likely to prescribe lower-cost medications.3 It is these types of savings that are expected to result in the most significant cost savings for the Medicare program.

Comparative Effectiveness Analysis

The National Institutes of Health is responsible for conducting or supporting comparative effectiveness research. Funding is to be used to accelerate the development and dissemination of research assessing the comparative effectiveness of healthcare treatments and strategies, including through efforts that: (1) conduct, support, or synthesize research that compares the clinical outcomes, effectiveness, and appropriateness of items, services, and procedures that are used to prevent, diagnose, or treat diseases, disorders, and other health conditions; and (2) encourage the development and use of clinical registries, clinical data networks, and other forms of electronic health data that can be used to generate or obtain outcomes data.

Comparative effectiveness work will be led by a new council. The Federal Coordinating Council for Comparative Effectiveness Research shall be composed of not more than 15 members, all of whom are senior federal officers or employees with responsibility for health-related programs, appointed by the President, acting through the Secretary of Health and Human Services. In addition, the IOM has been tasked with producing and submitting a report to the Congress and the Secretary by no later than June 30, 2009, that includes recommendations on the national priorities for comparative effectiveness research to be conducted or supported with the funds provided under the Stimulus Package.

This will set up a system by which Medicare and its providers will utilize studies and treatments based on research that demonstrates their effectiveness against other products in the Medicare population. The danger, of course, in this approach is how heavily restrictive the implementation of these findings become. If, for example, they move toward restricting access of care for certain individuals, it is likely that this approach will see a great deal of pushback.

Prevention/Wellness

This remains the Holy Grail—as noted in the AARP study—as previous attempts to gain a financial benefit from improved management of chronic diseases has yet to demonstrate any cost savings. Still, billions of dollars are set aside for prevention and wellness programs.

The Director of the National Institute of Standards and Technology in the Department of Commerce has been allocated almost $20 billion for continued work on advancing healthcare information enterprise integration through activities such as technical standards analysis and establishment of conformance testing infrastructure, as long as such activities are coordinated with the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology.

Under the Prevention and Wellness Fund are resources for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to carry out the immunization programs authorized, as well as to carry out chronic disease, health promotion, and genomics programs. An additional amount is provided to carry out domestic HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted diseases, and tuberculosis prevention programs. In addition, some $50 million is to be used by states to implement healthcare-associated infections reduction strategies. It is unclear what the return will be from these sizeable investments on both the health of our economy and the population.

Real Reform

Of course, much more will be revealed in the coming months, but clearly we are in the middle of a tidal wave of change for geriatric healthcare providers—a tidal wave of change that reveals itself each and every day. The most recent revelations are significant since they include the release of the President’s budget, nomination of Kansas Governor Kathleen Sebelius to head the Department of Health and Human Services, and recommendations from MedPAC on provider reimbursement. These MedPAC recommendations4 should be appreciated, as they are oftentimes followed by Congress. The recent recommendations include the following:

• Cut Medicare reimbursements for home healthcare providers by 5.5%, and maintain payments to skilled nursing facilities and inpatient rehabilitation facilities at current rates;

• Increase payment rates for acute inpatient and outpatient prospective payment systems by the projected increase to the hospital market basket index;

• Implement a quality incentive program for hospitals, funded by a 1% reduction in payments to indirect medical education programs;

• Increase payments to primary care providers and decrease payments to private insurers in Medicare Advantage;

• Pay Medicare Advantage plans the same as providers of regular FFS plans and receive higher payments only for better performance;

• Increase payments to physicians by 1.1%;

• Establish a budget-neutral payment system, giving primary care physicians higher payments and providing medical specialists payments funded by lower Medicare reimbursements.

With all of these changes, it is hoped by many that in the midst of all this change our frailest older adults are not forgotten, that our focus remains on providing quality care, and that we look toward cost reductions by decreasing utilization through prevention and improved management of chronic diseases by operating efficient and effective interdisciplinary care systems.

The author reports no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Stefanacci served as a CMS Health Policy Scholar for 2003-2004. He is Director of the Institute for Geriatric Studies at the Mayes College of Healthcare Business & Policy, University of the Sciences, Philadelphia, PA. Dr. Spivack is Associate Clinical Professor of Medicine, Columbia University, New York, NY; Consultant in Geriatric Medicine, Greenwich Hospital, Greenwich, CT; and Medical Director, LifeCare, Inc., Westport, CT.