Testing For Latent Tuberculosis and Performing Contact Investigation in the Nursing Home

Preventing active tuberculosis (TB) in nursing homes is a high priority. Prevention entails identifying newly admitted individuals who have latent TB and testing residents who have had contact with an individual with active TB, as may occur during a hospitalization. Until several years ago, a tuberculin skin test (TST) was the only modality available to screen for latent TB and to test exposed residents (contact investigation). Three blood tests, which work by detecting interferon released by sensitized T-cells, are now commercially available for this purpose, including T-SPOT.TB, QuantiFERON-TB Gold (QFT-G), and QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT). We report the case of a nursing home resident who was exposed to an individual with active TB during a hospitalization and discuss the use of TST versus blood tests for contact investigations.

Case Presentation

A frail 83-year-old woman returned to our nursing home, where she has been a resident for 4 years, after a 10-day hospital stay. In the hospital, she was treated for left middle and upper lobe pneumonia. The patient had a history of moderate dementia, seizure disorder, hypertension, and hypothyroidism. Upon admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), she was receiving bilevel positive airway pressure for hypoxia and intravenous vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam for healthcare-associated pneumonia. After 6 days in the ICU, she was transferred to a double room, where she stayed until discharge.

For the last 4 days of her hospital stay, her roommate was a young woman being treated for community-acquired pneumonia and a lung abscess. Forty-eight hours after the patient returned to the nursing home, we were informed that her roommate had active TB, diagnosed by positive sputum smears and an aspiration specimen from the lung abscess. Upon being admitted to the nursing home 4 years earlier, the patient underwent a two-step purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test, which was negative. TST testing was repeated 4 days after her return to the nursing home from the current hospital admission and was negative.

A QFT-GIT test performed 1 week after her return was also negative. A chest radiograph done 6 weeks after her hospital stay showed complete resolution of her pneumonia. The QFT-GIT test was repeated 2 months later and was negative. A TST was also repeated 8 weeks after her return from the hospital and was negative. The initial sputum cultures on the patient’s roommate subsequently grew Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Discussion

Nursing home residents should be screened for latent TB because they reside in an environment where there is an increased concentration of susceptible individuals, and the rate of TB reactivation increases with age.1 Before blood tests measuring T-cell interferon release were available, latent TB was defined as “a positive TST result in an asymptomatic person exposed to TB with no clinical or radiographic signs of active TB.”2 TST was the only method for detecting latent TB for 110 years, which was largely due to the false impression that TB ceased being a public health risk following the advent of effective antimicrobial therapy in 1946. As a result, little effort or funding was directed toward improving diagnostic methods. With TB infection rates increasing over the last 20 years, however, interest in developing other testing methods grew.

TB Blood Tests

TB testing methods that have become available over the last several years are based on the ex-vivo measurement of interferon-gamma released by circulating T cells or mononuclear cells in response to specific M. tuberculosis antigens. Development of these testing methods was made possible by advances in the delineation of the M. tuberculosis genome. Proteins encoded by sequences in the genome that are not present in the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine or in most environmental mycobacteria are used in the tests. These proteins include early secretory antigenic target-6 (ESAT-6), culture filtrate protein-10 (CFP10), and TB 7.7-p4, all of which induce a strong T-cell response by producing interferon-gamma (a cytokine).

Over the last 20 to 30 years, three interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs) have been developed and are now approved for use in the United States: an enzyme-linked immunospot (T-SPOT.TB) and two enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs; QFT-G and QFT-GIT).2 The T-SPOT.TB test, which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in June 2008, exposes peripheral mononuclear cells that have been separated from whole blood to specific TB antigens in wells coated with antibody to interferon-gamma. Mononuclear cells that were previously exposed to M. tuberculosissecrete interferon-gamma, which is bound to the antibody, and this antibody-interferon complex is chemically marked and counted.

The QFT-G and QFT-GIT were approved by the FDA in 2005 and 2007, respectively; the latter test incorporates a third TB antigen, TB 7.7-p4. The QFT-GIT test kit includes three tubes: a nil tube with no antigen, a tube containing three TB antigens (ESAT-6, CFP10, and TB 7.7-p4), and a mitogen tube. A sample of the patient’s blood is taken into each tube and the amount of interferon-gamma in the plasma of each tube is measured by ELISA after 16 to 24 hours of incubation and centrifugation for 15 minutes at 2000 to 3000 RCF (g) within 3 days of incubation.3 The nil and mitogen tubes serve as controls and help identify indeterminate results. For example, if both the mitogen and TB antigen tubes show low levels of interferon-gamma, this could indicate immunosuppression or mishandling of samples.4

Tuberculin Skin Test

The TST stimulates a delayed hypersensitivity reaction, which is a cell-mediated immune response (CMIR). This testing method has flaws, as immunosuppressed individuals may have reduced CMIR, resulting in a decreased sensitivity to TST. The test is also nonspecific for latent TB because individuals who have received the BCG vaccine or have had prior exposure to various naturally occurring mycobacteria may react to TST. In addition, errors can result from a variety of technical factors, including improper administration of the test and result assessment by an untrained examiner. To ensure accuracy, the correct dose of testing material must be properly injected intradermally and the results interpreted by a trained examiner within a specific time frame (48-72 hours), but even with trained examiners, there is inter-reader variability, which can skew results.3 Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of TST and the three IGRA tests.5-9

The TST stimulates a delayed hypersensitivity reaction, which is a cell-mediated immune response (CMIR). This testing method has flaws, as immunosuppressed individuals may have reduced CMIR, resulting in a decreased sensitivity to TST. The test is also nonspecific for latent TB because individuals who have received the BCG vaccine or have had prior exposure to various naturally occurring mycobacteria may react to TST. In addition, errors can result from a variety of technical factors, including improper administration of the test and result assessment by an untrained examiner. To ensure accuracy, the correct dose of testing material must be properly injected intradermally and the results interpreted by a trained examiner within a specific time frame (48-72 hours), but even with trained examiners, there is inter-reader variability, which can skew results.3 Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of TST and the three IGRA tests.5-9

CDC Guidelines on TB Testing

In June 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published updated guidelines on the use of FDA-approved IGRA tests to detect M. tuberculosis based on an expert committee’s review of the scientific evidence regarding these tests.10 The CDC identified 152 potentially relevant published articles, of which 96 primary reports were selected and reviewed by the committee. Although the reports showed varying sensitivities for QFT-GIT and T-SPOT.TB, the sensitivities of both of these IGRAs were found to be similar to TST.

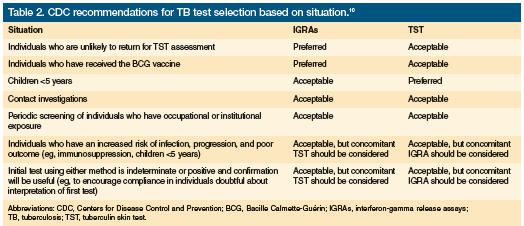

The specificity of QFT-GIT and T-SPOT.TB was generally reported to be greater than TST, but caution was advised in interpreting the study results because of differences in study populations and test interpretation standards. In addition, the results of each IGRA and TST are not interchangeable, as each test uses different antigens, measures different aspects of the immune response, and has its own interpretation criteria. Further, assessments of accuracy are hampered by the lack of a gold-standard test to confirm a diagnosis of latent TB or culture-negative active TB. Because accuracy cannot be confirmed, specificity (proportion of true negatives having negative test results) and sensitivity (proportion of true positives with positive test results) can only be determined by approximation using surveys in selected populations. Before selecting a test, providers need to consider test characteristics, the setting in which the test will be used, and the population to be tested. Providers also need to remember that none of these tests can conclusively rule out TB infection. The CDC guidelines present general recommendations and comments about test selection in different clinical situations, which are outlined in Table 2.10

Contact Investigations

The CDC guidelines note that QFT-GIT and T-SPOT.TB can be used in all situations where TST is appropriate, including for contact investigations. Some evidence suggests that IGRAs may be more useful than TST for contact investigations, as interferon-gamma release following TB exposure would theoretically be detected more rapidly than a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to TST. This was demonstrated in a Dutch study that found an association between blood test results (especially QFT-GIT) and measures of recent TB exposure, but no correlation between TST and exposure was observed; however, the study’s overall data were conflicting.11

TB Testing in Nursing Home Residents

Until recently, TST was the only test available for detecting latent TB in the nursing home. All new residents were required to undergo a two-step PPD skin testing protocol.12 Retesting with TST was performed if a resident was thought to have been exposed to TB. With the availability of blood tests, initial testing of new nursing home residents can be a one-step procedure. The blood tests can also be used for contact investigation. We assessed our patient using both TST and QFT-GIT because of her age, frailty, prolonged exposure to TB, and status as a nursing home resident.

Conclusion

Blood tests detecting T-cell interferon release can be used in all situations where TST was previously the only option. Latent TB infection should now be defined as “a positive TST result or a positive result using an FDA-approved blood test measuring T-cell interferon release in an asymptomatic person exposed to TB with no clinical or radiographic signs of active TB.” Accumulating evidence shows that the three available blood tests may have advantages in specificity and, in general, have equal sensitivity to TST. The ease of use with blood tests to detect TB in nursing home residents may be advantageous; however, further studies are needed to clarify which modality of testing is more cost-effective in this setting in the United States.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Warrington is coordinator geriatric experience, Crozer-Keystone Family Medicine Residency Program, Springfied, PA; and Dr. Srulevich is faculty member, Division of Geriatric Medicine, Crozer-Chester Medical Center, Upland, PA, and assistant professor of medicine, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

References

1. Thrupp L, Bradley S, Smith P, et al; SHEA Long-Term Committee. Tuberculosis prevention and control in long-term-care facilities for older adults. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25(12):1097-1108.

2. Lalvani A. Diagnosing tuberculosis infection in the 21st century: new tools to tackle an old enemy. Chest. 2007;131(6):1898-1906.

3. Spokane Regional Health District. QuantiFERON–TB Gold Tuberculosis Test (In-Tube Method) QFT-IT Healthcare Provider Information. www.srhd.org/documents/Health_Topics/TB-QFT-IT-ProviderInfo.pdf. Accessed October 20, 2010.

4. Miranda C, Tomford JW, Gordon SM. Interferon-gamma-release assays: better than tuberculin skin testing? Cleve Clin J Med. 2010;77(9):606-611.

5. Cellestis. Quanti-FERON®-TB Gold In-Tube. Accessed October 20, 2010.

6. Farhat M, Greenaway C, Pai M, Menzies D. False-positive tuberculin skin tests: what is the absolute effect of BCG and non-tuberculous mycobacteria? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(11):1192-1204.

7. von Reyn CF, Horsburgh CR, Olivier KN, et al. Skin test reactions to mycobacterium tuberculosis purified protein derivative and mycobacterium avium sensitin among health care workers and medical students in the United States. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5(12):1122-1128.

8. Andersen P, Munk ME, Pollock JM, Doherty TM. Specific immune-based diagnosis of TB. Lancet. 2000;356(9235):1099-1104.

9. Kendig El Jr, Kirkpatrick BV, Carter WH, et al. Underreading of the tuberculin skin test reaction. Chest. 1998;113(5):1175-1177.

10. Mazurek M, Jereb J, Vernon A, et al; IGRA Expert Committee; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated guidelines for using interferon-gamma release assays to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection-United States, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-5):1-25.

www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5905a1.htm. Accessed October 20, 2010. 11. Arend SM, Thijsen SF, Leyten EM, et al. Comparison of two interferon-gamma assays and tuberculin skin test for tracing tuberculosis contacts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(6):618-627.

12. American Geriatrics Society. American Geriatrics Society position paper. Two step PPD testing for nursing home patients on admission. Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging. 2006;14(2):38-40.