Taking the Pain Out of Compliance with F-Tag 329: Meeting the Challenges Through Collaboration, Part II

This is part II of a two-part article. Part I appeared in the October issue of the Journal.

Nursing facilities and physicians are still trying to interpret and address the expectations related to CMS’ December 2006 update of the Unnecessary Drug Surveyor Guidelines (F-TAG 329). Numerous medications are available, and the medication regimens of most nursing home residents are lengthy. The challenge for the practitioner is to identify a safe, effective medication regimen that minimizes the risk of having adverse consequences. In addition, both the practitioner and facility are expected to identify and address significant adverse medication consequences. This two-part article reviews several strategies for compliance, based on effective use of the care delivery process and a productive alliance between the practitioner, the consultant pharmacist, and other key facility leadership. (Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2008;16[11]:11-16)

Dr. Saffel is a certified geriatric pharmacist and President of Pharmacare Strategies, Santa Rosa Beach, FL; and Dr. Levenson is a multi-facility medical director in Baltimore, MD.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction

In December 2006, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued updated guidance for nursing home surveyors on the topic of medications.1 This update was a comprehensive overhaul of previous guidance on the subject.

The F329 guidance emphasizes the use of medications in the proper context, to try to provide the greatest possible benefit with the least possible harm. It promotes scrutiny of the entire medication regimen, for both short-stay and long-stay residents. It directs surveyors to seek more specific information about the clinical basis for a decision to use medications, not just a diagnosis or a declaration that the patient needs it. In addition, it reinforces the intent of the original regulation to balance the risks and benefits of all medications, not just psychopharmacologic medications.

Although physicians and consultant pharmacists are the primary disciplines involved in selecting and evaluating medications, the guidance emphasizes a facility-wide responsibility for safe and effective medication use. An interdisciplinary approach is desirable because medications impact all aspects of care, and the input of various disciplines can provide additional insights into the patient’s need for and response to medications.

To these ends, the F329 guidance promotes the care process, including pertinent discussions among the staff, patients, families, and practitioner about the causes of symptoms and the potential benefits and risks of medications, and a thorough search for, and review of, the background for a medication regimen (ie, when and why a medication was initiated, added, or changed).

Part I of this article discussed managing the challenges to healthcare practitioners, reviewing and understanding the surveyor guidance, and respecting the evidence about medications. Part II discusses the care process, including considerations related to tapering medications, and provides case examples related to improving F329 compliance.

Managing the F329 Challenge

The F329 surveyor guidance challenges nursing home staff and healthcare practitioners to consider medications in the context of the whole patient care process, rather than being a distinct activity. Although the F329 guidance was written to guide surveyors, the staff and practitioners can use the principles and information in the guidance to improve compliance while giving optimal care.

Part I of this article discussed two of the three key approaches that can make compliance with F329 feasible and relatively painless: reviewing and understanding the F329 surveyor guidance, and respecting the evidence about medications. The third key approach, thinking about care process, is discussed below.

Think About Care Process

The F329 guidance recognizes how systematically gathering detailed information about patients can facilitate rational clinical decisions about medications. The care process is a systematic, universally applicable approach to evaluating a patient’s physical, functional, and psychosocial symptoms, issues, and risks. Its use permits a more efficient and consistent approach to care by considering how specific symptoms and proposed interventions relate to the whole patient, no matter what the problem. Its steps have been identified as: (1) Recognition/Assessment; (2) Diagnosis/Cause Identification; (3) Treatment/Management; and (4) Monitoring. It is the healthcare adaptation of basic problem-solving techniques, the scientific method, and quality improvement approaches.2

Thus, practitioners can facilitate compliance with F329 by promoting and following a systematic care process. The administrator, medical director, director of nursing, and consultant pharmacist help the facility establish optimal working relationships among healthcare practitioners, residents and families, and direct care staff.

For example, studies have shown that the patient history is most likely to help physicians reach a correct diagnosis, which is critical to effective patient management.3 Adequate symptom detail is needed to develop a clear issue statement: What exactly is the problem or concern, and is it clinically significant enough to pursue and treat?

Adequate problem definition and diagnosis requires knowing where to look, what to look for, how to look for it, how to know when you’ve found what you are seeking, how to describe findings appropriately, and what to do with the information that is found. While physicians are trained to do these things in depth, they must rely on contributions from others in order to do them well.

Staff can influence medication prescribing and utilization by the way they describe, document, and report patient symptoms and other observations, conclusions, and recommendations to the practitioner. The practitioner also depends on the staff to recognize and report enough information to permit identification of suspected adverse consequences.

Every situation involving medication considerations should include enough information to “tell the story” of what has happened to the patient, and permit a thoughtful differential diagnosis. Unfortunately, nursing home patients rarely communicate directly with the physician or in any depth. Superficial reports of symptoms from nursing home staff are common but largely unhelpful. Examples might be “The resident complains of pain, and would like an order for something,” “The resident is coughing, so we would like an order for cough medication,” or “The resident is falling, so we need an order for a urine culture and some antibiotics.”

Practitioners should seek detailed information about their patients. In addition, they should collaborate with facility staff and management to ensure that they are given relevant, detailed information, especially when medication therapy may be considered. Since many laypersons are capable of describing their symptoms in detail, a nursing home should be able to train all levels of staff to provide symptom detail, not just superficial symptom statements.

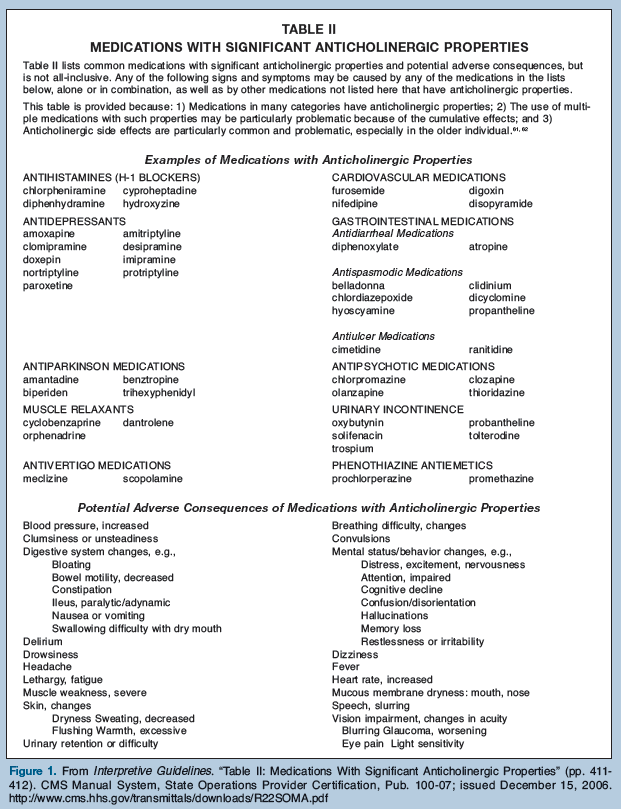

In guiding the practitioners, the medical director emphasizes key approaches such as asking for details of symptoms and always considering medications in the differential diagnosis of acute changes of condition. The director of nursing has nursing staff focus on adequate and detailed assessment and reporting to physicians, and reference to Tables I and II (Figure) of the Interpretive Guidelines to guide care conferences and patient reviews. Aided by the F329 guidance, which is written to be understood by nonclinicians, the administrator promotes the care process and key principles related to medication utilization. For example:

• Staff should not ask practitioners for specific medications but should focus on obtaining and providing adequate details of symptoms and issues.

• The staff and practitioner can use the F329 guidance to help identify medications that present a risk of clinically significant adverse consequences and situations or symptoms that could reflect those adverse consequences.

The consultant pharmacist can play a key role by collaborating with healthcare practitioners to provide clinically meaningful information to support medication therapy recommendations.4 During the required medication management review, the consultant pharmacist can identify information about the patient’s expected and actual response to medication including: changes in condition (both positive and negative) that may result from medication therapy, relevant patient history and physical and psychological assessments available on the chart, potential clinically significant drug-drug interactions, and therapy options such as dose tapering, medication discontinuation, and alternative medications.

The F329 guidance emphasizes nonpharmacological interventions, wherever possible. The staff and practitioner should consider these approaches in various circumstances, such as distressed behavior that is not due to psychiatric illness, providing heat or cold for musculoskeletal pain, and addressing causes of anorexia instead of giving alleged “appetite stimulants” that do not address the underlying cause.

The F329 guidance lists various situations when it is prudent to reconsider the medication regimen; for example, admission or re-admission; a new, persistent, or recurrent clinically significant symptom or problem; or an unexplained decline in function or cognition. When talking with staff about patients (whether by phone or in person) about these or other situations, it is prudent for practitioners to ask for a complete list of current medications. Take advantage of such opportunities to review the medication regimen related to indications, dosage, duration, and possible adverse consequences. Don’t assume that staff will provide them spontaneously or that they recognize medications in the regimen that could be causing current symptoms.

Care Process Considerations Related to Tapering Medications. The F329 guidance emphasizes appropriate dose and duration for each medication and minimizing the risk of adverse consequences. An appropriate dose is one where an individual receives the greatest possible benefits with the fewest possible undesirable side effects or adverse consequences; for example, controlling blood pressure enough to try to prevent a heart attack or a stroke but not so much to cause depression, persistent dizziness, or recurrent falling.

One approach is to act before initiating medication (the “front-end” approach). For example:

• Use nonpharmacological interventions wherever possible, in addition to or instead of medications to manage various symptoms and risks.

• Determine that a condition, symptom, or risk does not require a treatment or that a medication is not indicated as a treatment option.

• Initiate the lowest possible dose consistent with the risk or condition being addressed.

• Consider factors such as other medications in the regimen and existing risk factors (e.g., the increased risk of bleeding before initiating an anticoagulant or the risk for falls before starting medications for sleep or blood pressure that can impair balance or cause orthostatic hypotension).

There are also ways to try to optimize the dose and minimize complications after a medication has been initiated and while it is being continued (the “back-end” approach). The guidance expands expectations for considering medication tapering (also called “gradual dose reduction” [GDR] when it applies to psychopharmacologic medications). Although this is a challenging area for many staff and healthcare practitioners, certain approaches can greatly facilitate compliance.

The practitioner plays a key role in determining the reason symptoms may persist despite taking medications intended to treat them, or why they occur or recur after trying to taper or stop a medication. For example:

• The original diagnosis may need to be reconsidered.

• A new condition or problem may have arisen.

• The condition or its causes may not be readily treatable.

• The situation may require a higher dose of medication or additional medications.

• The existing medications may not be effective or indicated.

• The cause(s) of the symptoms may still be active and may require additional or different interventions.

• One or more medications in the existing medication regimen may be causing adverse consequences.

• A completely different approach may be indicated.

Using the care process fully can facilitate these decisions about dose and duration. Tapering medications can help the staff and healthcare practitioner to do the following:

• Identify whether symptoms or underlying causes have improved or resolved.

• Determine whether a medication is actually helping, whether a resident might do equally well with a lower dose, or whether the condition is improving irrespective of the medication.

• Identify whether a resident may be experiencing any adverse consequences related to a medication, especially if there are persistent, new, or worsening symptoms.

• Identify situations where the initial or working diagnosis or rationale for treatment may need to be reconsidered.

• Identify situations where a totally different intervention or medication may be indicated.

Thus, tapering a medication can often benefit both the patient and the facility. However, the F329 guidance recognizes that:

• Tapering or GDR is not always indicated.

• Tapering or GDR can potentially result in a return of target symptoms, sometimes unpredictably.

• Even when tapering is indicated, it may be done in several different ways.

Practitioners can help the facility demonstrate the appropriateness of its decisions about tapering medications in several ways:

• Clarify and document the rationale (ie, symptom or risk basis) for starting and continuing medication.

• Collaborate with the facility staff and consultant pharmacist to monitor the effectiveness and potential adverse consequences of the medication.

• Attempt a GDR for psychopharmacological medications in accordance with the requirements, or explain clearly why the symptoms or risks did not justify starting or continuing a dose reduction.

• Collaborate with the staff and consultant pharmacist to monitor efforts to taper various medications (e.g. whether symptoms returned or worsened and related causes, which could be due to something other than stopping or reducing a medication).

Examples Related to Improving F329 Compliance

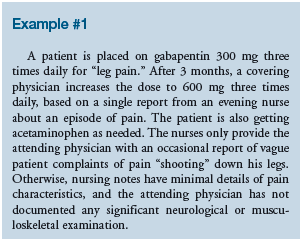

This case has numerous issues that need clarification, where better adherence to the care process can help. More and better detail is needed about the nature of the pain. The attending physician may need to contact the medical director or director of nursing, and ask more questions of the nursing staff when they report symptoms. The director of nursing can check the amount and quality of nursing documentation (onset, location, characteristics) about pain. It may be necessary to require nursing staff to report to a unit manager or nursing supervisor before calling physicians to ensure that they obtain and organize relevant information. The practitioner should ask the patient and nursing staff to compare the nature and severity of current pain complaints to those previously documented. The consultant pharmacist and nursing staff may be able to help the practitioner identify the evidence that the pain is truly neuropathic: What details (e.g., location, nature, duration, intensity) or test results are available to differentiate from other kinds of pain?

The practitioner may need to conduct an additional evaluation to try to identify causes of the pain, and to determine whether another, different cause may now be present. The nursing staff and consultant pharmacist should help identify whether any nonpharmacological measures were tried and their effect, if any. They should also determine when and whether the acetaminophen was being used and how it was decided whether and when to administer it.

The practitioner may need to reconsider the indication for using gabapentin. Not all “shooting” pain is necessarily neuropathic. Although it is common to use antiepileptic medications as analgesics for suspected neuropathic pain, their efficacy varies. These medications also have significant potential adverse consequences including dizziness, falling, and sedation. They may be used longer than necessary, and in higher doses than needed, thereby increasing complications while not necessarily improving pain.

The medical director and consultant pharmacist may need to familiarize practitioners regarding metoclopramide. It is commonly used by gastroenterologists and other physicians to treat gastrointestinal dysmotility and reflux disease. In addition, it may be added to the regimen of those who receive new feeding tubes. However, there is minimal evidence to support such widespread or routine use. The manufacturer’s literature about the medication notes that it “. . . is indicated as short-term (4-12 wk) therapy for adults with symptomatic, documented gastroesophageal reflux who fail to respond to conventional therapy. . . [and] for the relief of symptoms associated with acute and recurrent diabetic gastric stasis. Therapy longer than 12 weeks has not been evaluated and cannot be recommended.”5 Many nursing home patients are left on 5 mg or 10 mg four times daily for months or years without clear clinical indications. However, the medication is associated with significant adverse consequences, including extrapyramidal symptoms, movement disorders, psychosis, and lowered seizure threshold—especially problematic in the typical population residing in nursing homes.

The consultant pharmacist can help the physician identify whether there are—or ever were—any real indications for using this medication. The nursing staff and practitioner should review the symptom history and see whether any detailed descriptions or discussions of its onset, frequency, and other characteristics have been documented. Have the staff and physician been monitoring and discussing the status of the patient’s gastrointestinal symptoms? More details can help to characterize whether it is an isolated event or a problem needing an intervention.

Perhaps the original cause of any problem has resolved. Perhaps other medications in this patient’s regimen were, or still are, causing the problem. Perhaps the underlying cause cannot be reversed, and the metoclopramide is not really making any difference. Vomiting is not necessarily associated with aspiration, and aspiration does not necessarily cause pneumonia. Since there is no compelling evidence that metoclopramide routinely benefits those with a new feeding tube,6 why does this individual still need this medication?

Even if the individual had documented gastroparesis, the current dose may not be necessary. The consultant pharmacist can check for whether tapering has ever been attempted. The nursing staff, practitioner, and consultant pharmacist should all be reviewing for any signs of adverse consequences related to the medication (e.g., a delusional episode or seizure activity that may have resulted in a psychiatric consultation or antiepileptic medication prescription). If so, did anyone consider the possibility that such symptoms could have been related to metoclopramide?

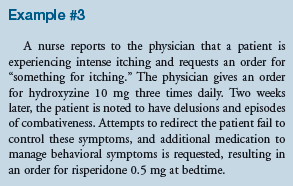

The medical director and director of nursing should check to see if the staff and practitioner attempted to determine the underlying cause for the patient’s itching. The consultant pharmacist can help the physician identify whether there are—or ever were—any real indications for using this medication, and whether alternative management might be more desirable.

Itching could indicate an allergic reaction, an expected or unexpected adverse drug effect, or can simply result from changes in environmental conditions such as dry conditioned air or changes in laundry detergent and skin soaps. Identifying the cause of itching can lead to more appropriate and effective interventions (eg, placing a humidifier in the patient’s room, using a non-allergenic soap, stopping a medication that is causing dry skin or pruritus).

The practitioner should reconsider the use of hydroxyzine. Itching associated with a topical reaction often responds to nonprescription skin lubricants or topical antipruritic agents, which reduces the risk of systemic effects that antihistamines may cause in susceptible individuals. Even if hydroxyzine is helping, the nursing staff and consultant pharmacist should discuss with the practitioner whether it is really needed routinely without a stop order. The director of nursing and medical director should review with the consultant pharmacist whether the facility needs a defined length of treatment (stop order) or require a review at certain intervals for symptomatic treatments. This approach can help to ensure that medications are not continued after the symptom has resolved, as well as to ensure that symptoms that continue despite treatment are reevaluated in a timely manner.

Summary

The topic of medications is vast, and there are many challenges associated with their safe and effective use. Even the most diligent healthcare practitioner is unlikely to be able to address all of these related issues without the input of others who care for and consult on the patients.

F329 provides many challenges to long-term care facilities including their staff, attending physicians, and consultants. But compliance with F329 essentially means using medications in a safe, effective manner that benefits the person who is receiving them and minimizes the occurrence of preventable, clinically significant adverse consequences. The F329 guidance for surveyors contains much information that can help facilities and practitioners comply more readily. A facility-wide initiative and a collaborative focus on the care process—instead of mere paper compliance—is the primary route to regulatory compliance.

Dr. Saffel is a speaker for Forest Pharmaceuticals and Abbott, and a consultant for Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, and Par Pharmaceutical. Dr. Levenson is a consultant to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Center for Medicaid & State Operations.