Taking the Pain Out of Compliance with F-Tag 329: Meeting the Challenges Through Collaboration, Part I

Nursing facilities and physicians are still trying to interpret and address the expectations related to CMS’ December 2006 update of the Unnecessary Drug Surveyor Guidelines (F-TAG 329). Numerous medications are available, and the medication regimens of most nursing home residents are lengthy. The challenge for the practitioner is to identify a safe, effective medication regimen that minimizes the risk of having adverse consequences. In addition, both the practitioner and facility are expected to identify and address significant adverse medication consequences. This two-part article reviews several strategies for compliance, based on effective use of the care delivery process and a productive alliance between the practitioner, the consultant pharmacist, and other key facility leadership. (Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2008;16[10]:29-34)

This is part I of a two-part article. Part II will appear in the next issue of the Journal.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction

Pharmacotherapy is a vast topic with a huge literature. Numerous medications are available, and many of them have diverse uses. Most nursing home residents take many medications, which have been initiated in various settings by a variety of healthcare practitioners. Depending on a number of factors, medications can potentially improve or worsen patient outcomes and care burden.

In December 2006, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued updated guidance for nursing home surveyors on the topic of medications.1 This update was a comprehensive overhaul of previous guidance on the subject.

The F329 guidance emphasizes the use of medications in the proper context, to try to provide the greatest possible benefit with the least possible harm. It promotes scrutiny of the entire medication regimen, for both short-stay and long-stay residents. It directs surveyors to seek more specific information about the clinical basis for a decision to use medications, not just a diagnosis or a declaration that the patient needs it. In addition, it reinforces the intent of the original regulation to balance the risks and benefits of all medications, not just psychopharmacologic medications.

Although physicians and consultant pharmacists are the primary disciplines involved in selecting and evaluating medications, the guidance emphasizes a facility-wide responsibility for safe and effective medication use. An interdisciplinary approach is desirable because medications impact all aspects of care, and the input of various disciplines can provide additional insights into the patient’s need for and response to medications.

To these ends, the F329 guidance promotes the care process, including pertinent discussions among the staff, patients, families, and practitioner about the causes of symptoms and the potential benefits and risks of medications, and a thorough search for, and review of, the background for a medication regimen (ie, when and why a medication was initiated, added, or changed).

Part I of this article discusses managing the challenges to healthcare practitioners, reviewing and understanding the surveyor guidance, and respecting the evidence about medications. Part II will discuss the care process, including considerations related to tapering medications, and provides case examples related to improving F329 compliance.

Challenges to the Facility and Healthcare Practitioners

Some healthcare practitioners, consultant pharmacists, and nursing home staff have readily endorsed the new guidance and incorporated its clinically sound approach into medication considerations. Others agree that they should be meeting its requirements, but are concerned about how they are going to comply in the face of limited time and reimbursement. Still others dismiss the guidance as an unfounded intrusion into their current clinical practices.

For practitioners who wish to comply, additional challenges abound. Pertinent information is often missing about when and why medications were begun or the basis for choosing certain doses. Nursing home residents often cannot give a history, and family or staff who can convey essential information may not be available. The medical record may lack adequate description of a resident’s symptoms and/or a medication’s effects or side effects. Possible adverse consequences may not be identified or reported in a timely fashion.

In addition, the impact of individual medications is often difficult to assess. Patients often have multiple comorbidities, impairments, and risk factors that influence the effects and adverse consequences of individual medications. The onset or exacerbation of a patient’s symptoms challenges healthcare practitioners to identify the significance of the symptom and the underlying causes, such as a new acute illness, exacerbation of chronic conditions, or medication side effects or interactions. Often, several causes coexist.

When symptoms stabilize, improve, or resolve, the healthcare practitioner is challenged to decide on a subsequent course. For example, underlying cause(s) may partially or totally resolve, eliminating the need for a medication or reducing subsequent dose requirements. But symptoms may not resolve or may recur or worsen due to, for example, erroneous medication selection, excessive or inadequate dosing, medication-related adverse consequences, or additional, recurrent, or untreatable causes. Thus, healthcare practitioners must make some key decisions about all patient symptoms and risk factors, including whether to do more evaluation and diagnostic testing, whether and how to modify the treatment regimen, and how much and how often to monitor.

Managing the F329 Challenge

The F329 surveyor guidance challenges nursing home staff and healthcare practitioners to consider medications in the context of the entire patient care process, rather than being a distinct activity.

Three key approaches can make compliance with F329 feasible and relatively painless:

- Review and understand the F329 surveyor guidance

- Respect the evidence about medications

- Always think “care process”

Review and Understand the Surveyor Guidance

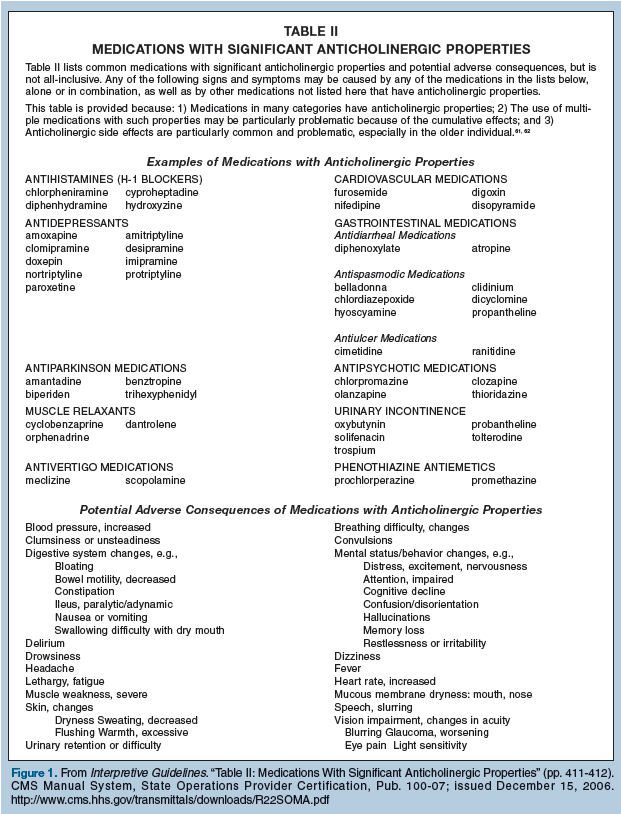

The F329 guidance includes three sections: the Interpretative Guidelines, the Investigative Protocol, and the Severity Determination. The Interpretative Guidelines review the intent of the regulation on medications and the expectations concerning medication management in nursing facilities. It includes “Table I: Medication Issues of Particular Relevance” (see pp. 372-411 of the Interpretive Guidelines) in caring for the nursing home population, including considerations for indications, dosage, duration, monitoring, and adverse consequences. A second table, “Table II: Medications With Significant Anticholinergic Properties,” (see pp. 411-412 of the Interpretive Guidelines) focuses specifically on medications with anticholinergic effects and side effects (Figure 1), which are especially common and problematic in this population.

The Investigative Protocol section tells surveyors what information to review in order to evaluate compliance. The Determination of Severity section gives examples of various levels of noncompliance with the F329 guidance, based on definitions of scope and severity that apply to all of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA ’87) regulations.

F329 gives practitioners many clues about what constitutes relevant documentation related to medication utilization. Documenting such information in the clinical record can help surveyors more readily identify compliance. Documentation does not have to be done all at once or repeatedly. Instead, the information should be there in the aggregate over time.

Practitioners and staff can demonstrate efforts to comply by following practices explicitly identified in the guidance: (1) try to use only those medications that are clinically indicated in the dose and for the duration to meet a patient’s assessed needs; (2) identify parameters for monitoring medication(s) or medication combinations that pose a risk for adverse consequences; (3) monitor the effectiveness of medications (including a comparison with therapeutic goals); (4) recognize and evaluate the onset or worsening of signs or symptoms or a change in condition to determine whether these potentially may be related to the medication regimen; and (5) follow up as necessary on identifying adverse consequences or failure to achieve a desired therapeutic response.

Practitioners should recognize what the guidance does and does not tell surveyors. The guidance does not tell physicians how to prescribe nor authorize surveyors to second-guess clinical decisions. It does, however, authorize surveyors to ask about the basis for medication prescribing and selection, the decisions about risks and benefits of specific medications, the attention to the medication regimen, the recognition of adverse consequences, the basis for not acting if adverse consequences are identified or suspected, the rationale for changing or maintaining a medication regimen, and reasons for choosing not to taper a medication when continued need for doses and duration is not clear.

Furthermore, the F329 guidance does not advocate that all effects can be monitored; that all adverse consequences can be anticipated, prevented, or detected; or that practitioners should always stop medications when adverse consequences are suspected or identified. Practitioners and staff should focus on clinically significant occurrences, which the guidance defines as “effects, results, or consequences that materially affect or are likely to affect an individual’s mental, physical, or psychosocial well-being either positively by preventing, stabilizing, or improving a condition or reducing a risk, or negatively by exacerbating, causing, or contributing to a symptom, illness, or decline in status.”

It can help both the staff and the practitioner to refer to a copy of the F329 tables when considering a patient’s medication regimen or symptoms that could be related to that regimen (eg, during case discussions and care conferences). Along with the required medication review, the tables in F329 can facilitate consideration of medications as a potential cause of emerging or worsening symptoms. The guidance encourages practitioners and staff to use additional medication references and resources—including the consultant pharmacist—as needed.

In the nursing home, one key to successful care is a coordinated effort among the medical director, director of nursing, and administrator. The administrator oversees the entire facility, including all departments and disciplines; the director of nursing oversees the department that delivers the majority of direct care; and the medical director is responsible (as identified in “F501, Medical Director,” in the OBRA regulations) for coordinating the medical care and overseeing implementation of all clinical policies in the facility.

Agreement among these three key individuals about the care process can enhance compliance with F329. The medical director promotes key medical and geriatrics principles, the director of nursing influences how information about residents is gathered and reported, and the administrator ensures that all disciplines coordinate their assessments and decision making.

We recommend that all three of these individuals read and then discuss F329 and its implications with the facility’s consultant pharmacist. This interdisciplinary review supports the development of facility-wide policies for medication management that emphasize the contributions of each discipline. The facility leadership should also encourage and help the practitioners to become familiar with the content.

Respect the Evidence

Although it is written to guide surveyors, the F329 guidance is a valuable summary of key medical and geriatric pharmacotherapy principles (eg, symptoms have causes and medications may cause symptoms similar to those related to medical illnesses). Because it is based on timeless clinical standards and well-documented evidence, its principles can be applied to the care of the elderly across multiple healthcare settings.

Evidence about the benefits and risks of medications in the elderly, and more specifically in the nursing home population, is readily available.2-4 The medical director, director of nursing, administrator, and consultant pharmacist should all be familiar with the evidence about medications, and know about at least some of the evidence related to specific medications listed in the tables for F329. For example:

• Symptoms often have remote causes, especially in patients with multiple comorbidities.

• Medications are often started or continued without clear indications, or despite resolution of symptoms or their underlying causes.

• Either alone or in combinations, medications can cause a variety of symptoms, which may be indistinguishable from medical illnesses due to non- medication causes.

• In general, the risk of adverse consequences increases as the number of medications increases.

Based on the evidence, the staff and practitioners in each nursing home should have a high index of suspicion when patients have symptoms listed in the table in the F329 Investigative Protocol (Figure 2) and are taking medications listed in Table I and Table II (Figure 1) of the Interpretive Guidelines. Not uncommonly, medications that by themselves may not be problematic may become so by interacting with other medications in a patient’s regimen.

There is concern about whether physicians take reports of possible medication-related adverse consequences seriously.5 We recommend that a facility’s medical director and consultant pharmacist give the facility’s practitioners some of the published evidence about appropriate medication use in the nursing home population. It is also worthwhile to discuss medication-related issues with the practitioners during medical staff meetings; for example, give options for tapering, appropriate monitoring of medications listed in Table I of the surveyor guidance and how staff can help the practitioner determine if a medication is working or if it is causing undesirable effects. It may also help to discuss specific cases; for example, discuss patients who have had amiodarone toxicity, anorexia related to antidepressants or to nausea from opioid analgesics, or increased lethargy due to clonidine.

Summary

The topic of medications is vast, and there are many challenges associated with their safe and effective use. Even the most diligent healthcare practitioner is unlikely to be able to address all of these related issues without the input of others who care for and consult on the patients.

F329 provides many challenges to long-term care facilities including their staff, attending physicians, and consultants. But compliance with F329 essentially means using medications in a safe, effective manner that benefits the person who is receiving them and minimizes the occurrence of preventable, clinically significant adverse consequences. The F329 guidance for surveyors contains much information that can help facilities and practitioners comply more readily. A facility-wide initiative and a collaborative focus on the care process—instead of mere paper compliance—is the primary route to regulatory compliance.

Part II of this article, to be published in the next issue of the Journal, will focus on the care process, a systematic, universally applicable approach to evaluating a patient’s physical, functional, and psychosocial symptoms, issues, and risks.

Dr. Saffel is a speaker for Forest Pharmaceuticals and Abbott, and a consultant for Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, and Par Pharmaceutical. Dr. Levenson is a consultant to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Center for Medicaid & State Operations.