A Systematic Review of Spirituality and Dementia in LTC

A systematic review was conducted to document all articles addressing spirituality among residents with dementia in long-term care (LTC) facilities. Three major themes emerged: (1) the spiritual needs identified included preserving a sense of purpose, fostering meaningful connections with the surrounding world, and retaining a relationship with God; (2) effective strategies for assessing individual spiritual needs were identified (eg, 2-level method); and (3) clinical guidelines suggested the use of formal religious interventions (eg, prayer, spiritual reminiscence). These strategies increased recall ability and mood, and decreased agitation. This article is the first review on spirituality and dementia to focus strictly on LTC residents. The lack of methodologically rigorous studies underlines the need for future research. This review reveals the importance of policies and programs of Homes for the Aged to increase awareness of the spiritual needs of residents with dementia. (Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2010;18(10):41-47).

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction

The growth of the aging population emphasizes the importance of examining factors that impact the quality of life for older persons. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 2009 there were 39 million older adults living in the United States.1 The number of older adults age 85 years and over is projected to increase threefold by 2050.1 The prevalence of dementia increases exponentially with age from 1% at age 60 years to 30% at age 85 years.2,3

Currently, in the United States there are 5.3 million individuals living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.4 By 2050, this number is expected to rise to between 11 and 15 million.4 The annual cost of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia in this country is $172 billion.4 Additionally, there are 10.9 million unpaid caregivers providing assistance to persons with dementia.4 Dementia is a key determinant of long-term care (LTC) placement, with two-thirds of residents possessing a cognitive impairment.5 In 2008, 3.2 million Americans with cognitive impairments lived in LTC facilities.4 With the projected increase in the number of individuals living with dementia, there will be a corresponding demand for LTC facilities.

Many LTC facilities offer activities to engage residents and promote social inclusion. Individuals with cognitive impairments who participate in recreational therapy experience fewer behavioral issues, lower medication use, greater alertness, and fewer falls.6 Recreational therapists are employed to encourage residents to participate in a wide variety of activities, including social gatherings, board or card games, music therapy, and pet therapy.7 Many of these activities are modified to enhance the abilities of individuals living with dementia.

Caregivers have the ability to create or diminish an individual’s personhood in the ways in which they interact with individuals.8 Overall, the care provided to individuals with dementia has shifted toward a person-centered approach. This approach recognizes the uniqueness of each individual and his or her personal abilities and preferences. As the merits of person-centered care are recognized, more facilities are considering how to best implement this approach. Researchers have found evidence to suggest that some of the negative consequences associated with dementia may be mitigated or delayed by this approach to care.9 It is essential that a holistic approach is employed to address individual care needs, but the spiritual needs of individuals in LTC settings are often overlooked.

Spirituality extends beyond religion to include a person’s values or beliefs. Individuals may conduct their lives around identified sources of value that provide an existential or meaningful interpretation of life.10 Residents may enhance and promote their spirituality through activities such as meditating, gardening, and spending time in nature. The spiritual services available in LTC usually focus solely on Judeo-Christian religious affiliation. Increased diversity in spiritual practices necessitates that LTC institutions provide more variety in the spiritual services that they offer their residents. There are few studies related to spirituality in older adults with dementia. This systematic review will identify all studies on the topic, synthesize key themes in the literature, and provide direction for future research, practice, and policy.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted to document all articles addressing spirituality and residents with dementia in LTC facilities. The electronic search for relevant literature was conducted in January 2010 with the assistance of two professional librarians.

The 13 social science databases searched included ASSIA (1997-), Abstracts in Social Gerontology (2001-2005), AGELINE (1978-), Proquest Religion @ Scholar’s Portal (1986-), PsycArticles (1894-), PsycInfo (1806-), Social Service Abstracts (1979-), Sociological Abstracts (1952-), Social Science Abstracts (1984-), Canadian Periodical Index (1980-), Social Service Citation Index (1956-), Social Work Abstracts (1968-December 2009), and ATLA Religion Database (1899-). The eight medical databases searched included MEDLINE (1950-), EMBASE (1947-), AMED (1985-), Ovid Healthstar (1986-December 2009), CINAHL (1980-), SCOPUS—Social, Psychological, Education, and Criminological (1960-), TRIP, and Scirus (1900-). The six gray literature databases searched included Cochrane Library, the Campbell Library, OpenSigle, NHS Evidence, New York Academy of Medicine, and Social Care Institute for Excellence. The following keywords were used for searching the preceding databases: (dement* or alzheimer* or adrd) AND (“convales* home*” or “residential care” or “long term care” or “extend* care*” or “care home*” or “nursing home*” or “old age home*” or “home* for elderly” or “residential care” or “assist* living” or “skilled nursing facilit*” or “intermediate care facilit*” or “home* for the aged”) AND (spirit* or religi* or faith* or worship* or prayer* or medit* or god* or “pastoral care”).

We also searched the Dissertation Abstracts International (1997-) database using a modification of the aforementioned keywords; the terms “convales* home*,” “old age home*,” “intermediate care facility*,” and “pastoral care” were not included.

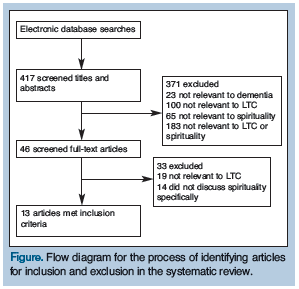

All of the searches combined yielded 417 unique hits (Figure). The title and abstract for each of these citations were then screened independently by two reviewers. Inclusion criteria were as follows: Each source had to focus strictly on persons with dementia, and its primary focus had to involve spirituality as a dimension of the dementia experience. Spirituality was defined in each respective study by the author. The setting had to be exclusively a LTC facility. Included sources were restricted to qualitative and quantitative studies, literature reviews, and clinical guidelines that focused specifically on the use of spirituality for individuals with dementia residing in LTC. There was no language restriction imposed on the sources, although all citations found were in English. There were 46 sources identified by both raters as needing a full-text review. The full text of each of the 46 sources was screened independently by two reviewers. From this final screening, 13 articles were selected to be included in the final review.

All of the searches combined yielded 417 unique hits (Figure). The title and abstract for each of these citations were then screened independently by two reviewers. Inclusion criteria were as follows: Each source had to focus strictly on persons with dementia, and its primary focus had to involve spirituality as a dimension of the dementia experience. Spirituality was defined in each respective study by the author. The setting had to be exclusively a LTC facility. Included sources were restricted to qualitative and quantitative studies, literature reviews, and clinical guidelines that focused specifically on the use of spirituality for individuals with dementia residing in LTC. There was no language restriction imposed on the sources, although all citations found were in English. There were 46 sources identified by both raters as needing a full-text review. The full text of each of the 46 sources was screened independently by two reviewers. From this final screening, 13 articles were selected to be included in the final review.

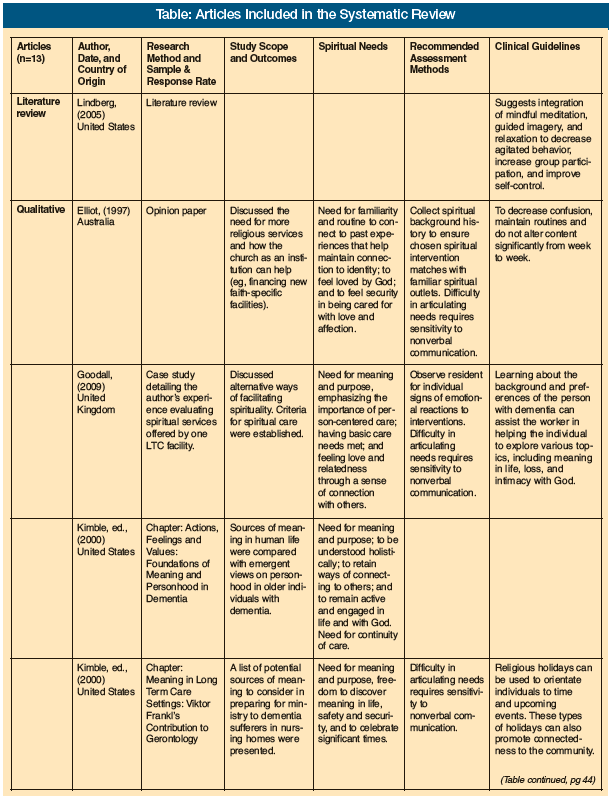

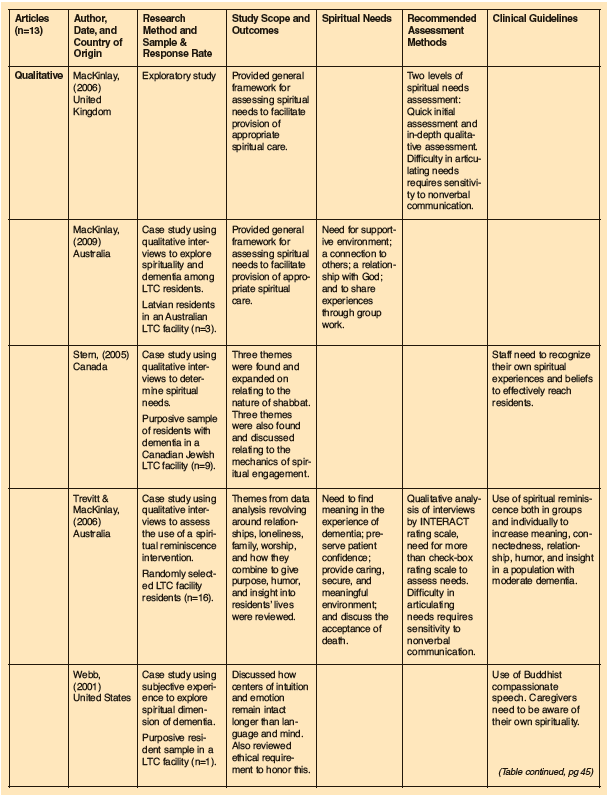

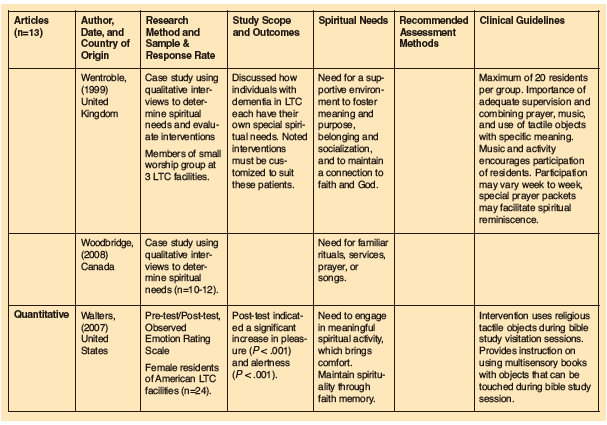

Three major themes were present in the 13 articles: spiritual needs; methods of assessment; and clinical guidelines. It must be noted that there is a dearth of rigorously conducted research on this topic. Only a single study had recommendations based on quantitative data.18 The others consisted of exploratory case studies, literature reviews, or personal reflections (Table).

Spiritual Needs

Eight articles characterized the spiritual needs of nursing home (NH) residents with dementia in a LTC setting.11-18 We identified three sub-themes that were present in these articles. The first theme addressed the need for individuals to maintain a sense of meaning and purpose.11-13 Preserving meaning and purpose in the lives of residents aids in maintaining quality of life and the will to live. This can be accomplished by providing appropriate interventions that include a spiritually supportive environment and mechanisms to help residents with dementia live fully in the present.11-15 In addition, offering a sense of control over decisions in daily life gives meaning to residents by fostering an integral sense of self.12-15 A sense of meaning and purpose leads to the development of effective coping strategies with the progressive symptoms of the disease. It allows individuals with dementia to make sense of their overall life experience. This, in turn, allows them to transcend losses related to dementia and come to an acceptance of their lives.12

The second theme consisted of the need for individuals to preserve meaningful connections with the world around them. Most individuals identified personal relationships as a key component to a meaningful spiritual life.12 Living with dementia requires a connection with others to maintain a sense of security and of belonging, and to sustain a reciprocal relationship of love with family, formal caregivers, or both.11,13-17 Consistent and meaningful relationships can preserve the confidence of the individual, help the individual to retain emotional responsiveness, and assist in his or her ongoing efforts to engage in life.12,13 By fostering interpersonal communication, the individual with dementia can maintain a greater sense of inner strength and comfort.13,15,16,18

The third theme identified the need for residents to have a relationship with God. Many individuals are afraid that their dementia is a punishment for the way that they have lived their lives, yet they still wish to retain an unconditional relationship with God.11-14,16 Acceptance of death may develop through discussions of the fears of being forgotten by God.12 Research suggests that providing forums for these discussions is a way of promoting and strengthening a relationship with God.12,16

Continued on next page

Methods for Assessing Spiritual Needs

Five articles discussed methods for assessing the spiritual needs of residents with dementia in a LTC setting.11-13,16,19 MacKinlay’s 2-level method of assessment addressed relevant personal spiritual themes and appropriate interventions.19 First, staff were asked to conduct a quick and general individual screening assessment upon admission. This may include obtaining information on the previous spiritual practices of the resident. This screening should directly involve the resident where communication is possible. The goal is to ensure that any spiritual intervention within the facility reflects familiar spiritual outlets in the lived experience of each resident.16 The next level of assessment incorporated staff members who are implementing spiritual interventions (eg, pastoral carers, other staff trained in pastoral care). They conducted in-depth spiritual assessments in the context of interviews. These assessments took into account themes such as formal religious practices, final life meanings, transcending losses, finding new ways to interact with others, and finding hope.19

Due to the varying and personal nature of spirituality, it is difficult to conduct a valid and reliable spiritual needs assessment of residents with dementia using a check-box scale, and more intuitive and observational criteria must be utilized.12,13 Staff members may begin by reviewing the information gathered on each individual during the initial screening assessment. While undertaking an intervention, staff members can assess how spirituality can be most effectively promoted through music, objects such as artifacts, and officials such as clergy.11 Finally, during spiritual interventions, staff members can assess the manner in which each resident displays emotional reactions and look for the presence or absence of these signs.11

The literature consistently emphasized that residents with dementia may have a difficult time articulating their spiritual needs,11,12,16,19 which makes collecting a spiritual history difficult.16 Spiritual assessments hinge on staff being cognizant of the emotions that persons with dementia display during religious services and other spiritual interventions. For example, an individual with dementia may not be able to verbalize a cause-and-effect relationship when a familiar spiritual piece of music evokes a calming feeling. Observing the emotional and physical reaction can cue staff members about the usefulness of music in bringing his or her spiritual sense of self to the forefront.12

Clinical Guidelines

Seven articles discussed clinical guidelines.11-13,16,18,20,21 The findings of studies that examine the role of spirituality and dementia in a LTC setting are only effective when translated into knowledge that can be applied to improve care for residents. These articles presented many suggestions to assist staff in providing spiritual care. Individuals with dementia residing in LTC facilities are dependent on healthcare professionals for many of their needs. Hence, the healthcare provider has an opportunity to influence the quality and level of spiritual care provided to residents.

Goodall,11 Stern,20 and Webb21 asserted that the staff member needs to be self-reflective in his or her own beliefs to explore spirituality with residents. Staff should strive to know the background and preferences of residents to help them with finding meaning in life, transcendence, building connections to nature and others, and promoting their intimacy with God.11,12 Goodall11 and Stern20 suggested that staff would benefit from identifying their own spiritual needs and engaging in pastoral theology training to better assist residents. Webb21 emphasized that caregivers need to get in touch with their own consciousness, including issues surrounding mortality. Caregivers can facilitate the connection of individuals to activities that provided them with meaning in the past, such as art, pets, gardening, and religious rituals.11 Webb21 discussed the use of “compassionate speech,” which is based on Buddhist beliefs, when caring for individuals with dementia. Compassionate speech is the careful selection of words that narrow the gap between us and others. To use compassionate speech, a healthcare provider would select vocabulary based on the individual’s current reality. By selecting language in this manner, the provider is able to become comfortable with the reality of persons with dementia.

The literature examined suggested that it is necessary to engage residents with spiritual interventions throughout the course of the disease.13,16 One pastoral worker discussed how she consistently used the same content and similar routines to decrease the confusion of the residents participating in her Sunday service.16 Some pastoral workers have found that religious holidays assisted residents with dementia in their orientation to time and helped to maintain connections to their community.13

Spiritual activities and reminiscence can provide participants with the opportunity to interact with others. One researcher noted the presence of frequent expressions of humor and laughter during group reminiscence that had not been present prior to the sessions.12 Wentroble15 outlined a method of conducting a spiritual group activity for people with dementia; the author stipulated that a maximum of 20 residents should participate with at least two facilitators so that one would be able to attend to any disruptions in the group. The activity should include elements of music, prayer, and tactile objects that encourage the participation of residents. Special reminiscence packets with different objects that are tailored to specific religions can be included in the pastoral care.15 Individuals who provided pastoral care to persons with dementia discovered that objects such as bibles and prayer cards seemed to be helpful in bringing back memories.15 Other researchers such as Walters18 agreed that tactile objects related to spirituality can be effective when working with people who have dementia. Multisensory books with objects that can be touched during bible study sessions were proven to be even more advantageous for individuals with dementia. The women included in Walters’ study displayed four times more pleasure when shown religious tactile objects and five times more pleasure when viewing the religious multisensory book than they did during sessions involving only a regular bible.18

In her article that reviewed meditation and spirituality in older populations, Lindberg22 demonstrated that meditative experiences such as mindfulness meditation, meditative prayer, and guided imagery have important effects on persons with dementia. These effects include improvements in agitation, hope, self-esteem, connectedness, and meaning. Individuals with profound cognitive impairment can perform meditative exercises with proper guidance and support from clinicians.22 Lindberg22 discovered that individuals with dementia who participated in this study experienced positive effects (less agitation and increased relaxation) for up to 2 hours after completing the exercise.

Discussion

Readers should be aware that we were only able to search for articles written in English. Despite this limitation, this systematic review was the first to focus on the needs and interventions for individuals with dementia in LTC. The 13 articles reviewed emphasized the importance of client-centered spiritual assessment and spiritual intervention to provide meaning and enhance quality of life.

Beuscher and Beck23 conducted a literature review of spirituality in individuals with early-stage dementia; however, their literature review was not specific to LTC residents. They focused solely on the spirituality of individuals with early dementia. The participants in the five articles they reviewed had an average Mini-Mental State Examination score of 21. The specific stage of dementia was not a point of emphasis in our articles. Our review included any article on spirituality of LTC residents with dementia regardless of the severity. One article we reviewed focused specifically on severe dementia.15 In the five articles assessed by Beuscher and Beck,23 97% of clients had formal religious identifications, making it possible that the discussion was specific to only organized religion rather than spirituality. On the other hand, in our review, the religiosity of the clients was not always as clearly identified.

Several conclusions of Beuscher and Beck’s23 review were similar to ours: (1) spiritual interventions have a positive effect on many aspects of a client’s quality of life; (2) person-centered care includes a clear understanding of the spiritual needs of residents with dementia; (3) formal caregivers can enhance spirituality, and therefore improve outcomes; (4) formal caregivers need to be self-aware about their own spiritual beliefs to provide optimal care; and (5) spirituality is personal and multidimensional.

Three major themes ran throughout the literature we examined. The initial theme covered spiritual needs identified for enhancing the quality of life of LTC residents with dementia. These included sense of meaning and purpose, feelings of connection to others, and a relationship with God (whether formal or informal). The idea that these are distinct areas of spiritual concern for LTC residents matches current literature on spirituality and early-stage dementia.23

The next theme emphasized the importance of assessing the spiritual needs of individuals. Screening assessments were outlined that aimed to garner a detailed understanding of the individual spiritual needs of residents with dementia. The articles suggested that communication difficulties were the main barrier to assessing the spiritual needs of these residents.

The final theme that ran throughout the literature identified clinical guidelines for effective spiritual intervention strategies. Among the strategies suggested are formal religious interventions such as prayer and bible study, compassionate speech, meditation, and spiritual reminiscence. The articles suggested that there were improvements in quality-of-life indicators, severity of behavioral problems, and observed resident contentment with spiritual interventions.

The strength of these conclusions is somewhat mitigated by methodological limitations of the studies reviewed. The majority of these studies had very small purposive samples, limiting the ability to generalize the results. A number of these articles originated from faith-based organizations; thus, the possibility of bias is present. There were no randomized, controlled studies, making it difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of the spiritual interventions.

Implications

This article identified a number of implications for practice and policies in LTC facilities. There needs to be an increase in the sensitivity and awareness of residents’ spiritual needs as a part of the culture of LTC facilities. Education of formal carers and the development of formal assessment tools for spiritual needs would be helpful in nurturing the understanding of spiritual needs and the development of spiritual interventions. Education of informal carers about spirituality is also necessary. Assessments of spirituality should be done as early as possible in the course of the person’s dementia.

The scantiness of solid knowledge uncovered through the review leads to a bevy of implications for future research. There is a lack of studies that are explanatory in nature. These need to be done to begin to build a better evidence base for the effectiveness of spiritual interventions. Valid and reliable quantitative scales need to be developed to measure the spiritual well-being of residents with dementia. It would be interesting to discern whether spiritual interventions have a different effect on residents who identify themselves as religious or nonreligious. Research should compare the relative effectiveness of person-centered social interventions such as reminiscence work with spirituality-based interventions. It would also be useful to study whether there is a threshold of cognitive impairment after which spiritual interventions may no longer be helpful.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Esme Fuller-Thompson for her guidance throughout the review process, along with University of Toronto librarians Carla Hagstrom, MLS, and Marian Press, MA, MLS, for their invaluable assistance with the search process, and Mary Anne Shoefly for her time and dedication in taking part in the independent article reviewing process. The authors report no relevant financial relationships. Mr. Keast, Ms. Leskovar, and Ms. Brohm are at the University of Toronto, Canada.

References

1. U.S. Census Bureau. Census Bureau reports world’s older population projected to triple by 2050. https://www.census.gov. Published June 23, 2009. Accessed September 13, 2010.

2. Weiner M, Lipton A, eds. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Alzheimer Disease and Other Dementias. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc; 2009.

3. Weiner MF, Hynan LS, Beekly D, et al. Comparison of Alzheimer’s disease in American Indians, whites, and African Americans. Alzheimers Dement 2007;3(3):211-216.

4. Alzheimer Association. 2010 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. https://www.alz.org/documents_custom/report_alzfactsfigures2010.pdf. Updated 2010. Accessed September 13, 2010.

5. Matthews FE, Dening T; UK Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study. Prevalence of dementia in institutional care. Lancet 2002;360(9328):225-226.

6. Buettner LL. Therapeutic recreation in the nursing home. Reinventing a good thing. J Gerontol Nurs 2001;27(5):8-13.

7. Ice G. Daily life in a nursing home-has it changed in 25 years? Journal of Aging Studies 2002;16(4):345-359.

8. Woods B. The person in dementia care. Generations 1999;23(3):35-39.

9. O’Connor D, Pinney A, Smith J, et al. Personhood in dementia care: Developing a research agenda for broadening the vision. Dementia 2007;6(1):121-142.

10. Ortiz LP, Langer N. Assessment of spirituality and religion in later life: Acknowledging clients’ needs and personal resources. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 2002;37(2):5-21.

11. Goodall MA. The evaluation of spiritual care in a dementia care setting. Dementia 2009;8(2):167-183.

12. Trevitt C, MacKinlay E. “I am just an ordinary person...”: Spiritual reminiscence in older people with memory loss. Journal of Religion, Spirituality and Aging 2006;18(2-3):79-91.

13. Kimble MA, ed. Viktor Frankl's Contribution to Spirituality and Aging. Haworth Pastoral Press, Binghamton, NY; 2000.

14. MacKinlay E. Using spiritual reminiscence with a small group of Latvian residents with dementia in a nursing home: A multifaith and multicultural perspective. Journal of Religion, Spirituality and Aging 2009;21(4):318-329.

15. Wentroble DP. Pastoral care of problematic Alzheimer’s disease and dementia affected residents in a long-term care setting. J Health Care Chaplain 1999;8(1-2):59-76.

16. Elliot H. Religion, spirituality and dementia: Pastoring to sufferers of Alzheimer’s disease and other associated forms of dementia. Disabil Rehabil 1997;19(10):435-441.

17. Woodbridge M. Soul sessions. J Dement Care 2008;16(4):14-15.

18. Walters D. The effect of multi-sensory ministry on the affect and engagement of women with dementia. Dementia 2007;6(2):233-243.

19. MacKinlay E. Spiritual care: recognizing spiritual needs of older adults. Journal of Religion, Spirituality and Aging 2006;18(2-3):59-71.

20. Stern B. Phenomenological approach towards understanding the nature and meaning of engagement in religious ritual activity: perspectives from persons with dementia and their caregivers. UMI Dissertation Services, ProQuest Information and Learning, Ann Arbor, MI; 2005.

21. Webb G. Intimations of the great unlearning: Interreligious spirituality and the demise of consciousness which is Alzheimer’s. Accessed September 14, 2010.

22. Lindberg DA. Integrative review of research related to meditation, spirituality, and the elderly. Geriatr Nurs 2005;26(6):372-377.

23. Beuscher L, Beck C. A literature review of spirituality in coping with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Nurs 2008;17(5A):88-97.