Point/Counterpoint: Treating Hypertension in the Elderly

Point: Treating Hypertension in the Elderly

An 83-year-old woman with a prior myocardial infarction (MI) had a blood pressure in the sitting position of 172/90 mm Hg in the right brachial artery and 174/90 mm Hg in the left brachial artery. Her standing blood pressures were similar. Her physician was uncertain whether he should treat her blood pressure because of differing published opinions,1,2 and because of a debate he had heard at a national meeting moderated by the author in which conflicting opinions were expressed. Should this woman be treated with antihypertensive drug therapy?

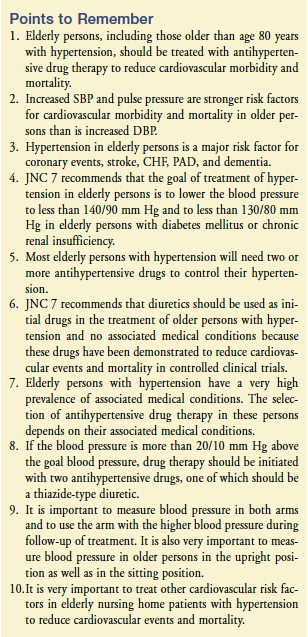

The answer is yes,3,4 and this article will discuss why. Hypertension was present in 57% of 1160 older men (mean age, 80 yr) and in 60% of 2464 older women (mean age, 81 yr) in a nursing home, with two-thirds of these older persons having isolated systolic hypertension.5 Of 1819 older persons (mean age, 80 yr) living in the community and seen in an academic geriatrics practice, 58% had hypertension (37% with isolated systolic hypertension).6

Target organ damage, clinical cardiovascular disease (CVD), or diabetes mellitus was present in 70% of older persons with hypertension.6 The prevalence of hypertension in older persons with diabetes mellitus in a nursing home was 76%.7 The higher the systolic blood pressure (SBP) or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) in older persons, the higher the cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.8

Increased SBP and pulse pressure are stronger risk factors for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in older patients than is increased DBP.9,10 An increased pulse pressure found in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension indicates decreased vascular compliance in the large arteries and is even a better marker of risk than is SBP or DBP.9,10 The Cardiovascular Health Study found in 5202 older men and women that a brachial SBP higher than 169 mm Hg increased the mortality rate 2.4 times.11

Hypertension in older persons is a major risk factor for coronary events,12-14 stroke,12,15-17 congestive heart failure (CHF),12,18,19 and peripheral arterial disease (PAD).20-23 Older persons are more likely to have hypertension and isolated systolic hypertension, to have target organ damage and clinical CVD, and to develop new cardiovascular events; they are less likely to have hypertension controlled. Barriers to treatment of hypertension include physicians not understanding that frail elderly patients should be treated according to recommended guidelines to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Elderly persons with hypertension, if treated appropriately, will have a greater absolute decrease in such cardiovascular events as major coronary events, stroke, CHF, and renal insufficiency, and a greater reduction in dementia24 than younger persons. Some elderly persons living in the community may not be able to afford their antihypertensive medications.25 Numerous prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studies have demonstrated that antihypertensive drug therapy reduces the development of new coronary events, stroke, and CHF in older persons.26

Therapy with antihypertensive drugs reduces the incidence of all strokes by 38% in women, by 34% in men, by 36% in older persons, and by 34% in persons older than 80 years.16 The overall data suggest that reduction of stroke in older persons with hypertension is related more to a decrease in blood pressure than to the type of antihypertensive drugs used.16 In the Perindopril Protection Against Recurrent Stroke Study,27 perindopril plus indapamide reduced stroke-related dementia by 34% and cognitive decline by 45%.

In the Systolic Hypertension in Europe trial,28 nitrendipine decreased dementia by 55% at 3.9-year follow-up. In 1900 older African Americans, antihypertensive drug treatment decreased cognitive impairment by 38%.29 In the Rotterdam Study,30 antihypertensive drugs decreased vascular dementia by 70%. On the basis of data available at the time, Aronow1 proposed in an editorial that unless the HYpertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET)3 showed that antihypertensive drug therapy was not beneficial in patients age 80 years and older, this group should receive antihypertensive drug treatment.

Goodwin2 disagreed with this approach, and his response to Aronow’s editorial was accompanied by eight commentaries, some of which supported the treatment of very elderly hypertensive patients and some of which did not. In HYVET, 3845 individuals age 80 years and older (mean age, 83.6 yr) with a sustained SBP of 160 mm Hg or higher (mean sitting blood pressure of 173.0/90.8 mm Hg) were randomized to indapamide (sustained release 1.5 mg) or matching placebo. Perindopril 2 mg or 4 mg, or matching placebo, was added if needed to achieve the target blood pressure of 150/80 mm Hg. Median follow-up was 1.8 years. At 2 years, the mean blood pressure was 15.0/6.1 mm Hg lower in the drug treatment group than in the placebo group.

In an intention-to-treat analysis, antihypertensive drug treatment reduced the incidence of the primary end point (fatal or nonfatal stroke) by 30% (P = 0.06). Antihypertensive drug treatment reduced fatal stroke by 39% (P = 0.05), all-cause mortality by 21% (P = 0.02), death from cardiovascular causes by 23% (P = 0.06), and heart failure by 64% (P < 0.001). The significant 21% reduction in all-cause mortality by antihypertensive drug treatment was unexpected. The benefits of antihypertensive drug treatment began to be apparent during the first year of follow-up. The prevalence of baseline CVD was only 12% in the patients in HYVET. In a cohort of patients (mean age, 80 yr) with hypertension seen in a university geriatrics practice, 70% had baseline CVD, target organ damage, or diabetes mellitus.6

An elderly population such as this one with a high prevalence of CVD would be expected to have a greater absolute reduction in cardiovascular events resulting from antihypertensive drug therapy. I agree with the recommendations of the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7)26 that the goal of treatment of hypertension in elderly persons is to lower the blood pressure to less than 140/90 mm Hg and to less than 130/80 mm Hg in older persons with diabetes mellitus or chronic renal insufficiency.

Elderly persons with diastolic hypertension should have their DBP reduced to 80-85 mm Hg.31 Most elderly persons with hypertension will need two or more antihypertensive drugs to control their hypertension.25,26,32 In elderly persons with hypertension in an academic nursing home, 27% received one antihypertensive drug, 43% received two antihypertensive drugs, 22% received three antihypertensive drugs, 6% received four antihypertensive drugs, and 3% received five antihypertensive drugs.32 It is important to measure blood pressure in both arms and to use the arm with the higher blood pressure during follow-up of treatment.33 It is also very important to measure blood pressure in older persons in the upright position as well as in the sitting position.

I agree with the recommendations of JNC 7 that diuretics should be used as initial drugs in the treatment of older persons with hypertension and no associated medical conditions, because these drugs have been demonstrated to reduce cardiovascular events and mortality in controlled clinical trials.26 However, elderly persons with hypertension have a very high prevalence of associated medical conditions. The selection of antihypertensive drug therapy in these persons depends on their associated medical conditions. If the blood pressure is more than 20/10 mm Hg above the goal blood pressure, drug therapy should be initiated with two antihypertensive drugs, one of which should be a thiazide-type diuretic.26

Elderly persons with prior MI should be treated with beta blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and not treated with alpha blockers or calcium channel blockers.34-42 In an observational prospective study of 1212 elderly men and women in a nursing home with prior MI and hypertension treated with beta blockers, ACE inhibitors, diuretics, calcium channel blockers, or alpha blockers, at 40-month follow-up, the incidence of new coronary events in persons treated with one antihypertensive drug was lowest in older persons treated with beta blockers or ACE inhibitors.41 In older patients in a nursing home treated with two antihypertensive drugs, the incidence of new coronary events was lowest in persons treated with beta blockers plus ACE inhibitors.41

The benefit of beta blockers in reducing new coronary events in elderly patients with prior MI is especially increased in elderly patients with diabetes mellitus,37 PAD,38 abnormal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF),36 complex ventricular arrhythmias with abnormal LVEF43 or normal LVEF,44 and CHF with abnormal LVEF45 or normal LVEF.46 Beta blockers should also be used to treat elderly patients with hypertension who have angina pectoris,47 myocardial ischemia,48 supraventricular tachyarrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular rate,49,50 hyperthyroidism,51 preoperative hypertension,26 migraine,26 or essential tremor.26 Beta blockers such as propranolol, timolol, metoprolol, and carvedilol should be used to treat older persons with MI.52 Beta blockers with intrinsic sympathomimetic activity should not be used to treat patients after MI. The hydrophilic beta blocker atenolol is not as efficacious as propranolol, timolol, metoprolol, or carvedilol in treating hypertension in older persons.52,53

In addition to beta blockers, older persons with CHF should be treated with diuretics and ACE inhibitors.54,55 ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers (ARBs) should be administered to older persons with diabetes mellitus, chronic renal insufficiency, or proteinuria.26 Compared with amlodipine, ramipril significantly decreased progression of renal disease in 1094 African Americans with hypertensive nephrosclerosis.56 If the older patient cannot tolerate an ACE inhibitor because of cough, angioneurotic edema, rash, or altered taste sensation, an ARB should be administered.57

Compared to ramipril alone, addition of telmisartan to ramipril in patients (mean age, 67 yr) with vascular disease or high-risk diabetes mellitus did not improve the efficacy of the primary outcome of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, or hospitalization for heart failure at 56-month median follow-up, but increased hypotensive symptoms (4.8% vs 1.7%), syncope (0.3% vs 0.2%), and renal dysfunction (1.1% vs 0.7%).58 Diuretics and ACE inhibitors are recommended by JNC 7 to prevent recurrent stroke in older persons with hypertension.26,27 Thiazide diuretics should be used to treat older patients with osteoporosis.26

It is very important to treat other cardiovascular risk factors in elderly nursing home patients with hypertension to reduce cardiovascular events and mortality. Smoking must be stopped. Dyslipidemia must be treated.59-62 Diabetes mellitus must be controlled.3,63-67 Because the woman in the case above had a prior MI, she should be treated with aspirin, a beta blocker, a statin to reduce her serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol to less than 70 mg/dL, and an ACE inhibitor.68

The initial antihypertensive drug should be administered at the lowest dose and gradually increased to the maximum dose. If the antihypertensive response to the initial drug is inadequate after reaching the full dose of drug, a second drug from another class should be given if the person is tolerating the initial drug. If the person is having no therapeutic response or significant adverse effects, a drug from another class should be substituted. If a diuretic is not the initial drug, it is usually indicated as the second drug. If the antihypertensive response is inadequate after reaching the full dose of two classes of drugs, a third drug from another class should be added.

Before adding new antihypertensive drugs, the physician should consider possible reasons for inadequate response to antihypertensive drug therapy, including nonadherance to therapy, pseudoresistance, volume overload, drug interactions (eg, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, caffeine, antidepressants, nasal decongestants, sympathomimetics), and associated conditions such as increasing obesity, smoking, excessive intake of ethyl alcohol, and insulin resistance.26 Causes of secondary hypertension should be identified and treated.26,69 Falls or syncope in older persons may be due to orthostatic or postprandial hypotension.70

All antihypertensive drugs, especially diuretics, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, calcium channel blockers, and nitrates, may predispose the elderly person to develop symptomatic orthostatic hypotension and postprandial hypotension, and syncope or falls.70 Diuretics may cause volume depletion. Vasodilators such as ACE inhibitors, ARBs, calcium channel blockers, hydralazine, nitrates, and prazosin may cause a decrease in systemic vascular resistance and venodilation. The decrease in baroreflex sensitivity with age and with hypertension leads to impaired baroreflex-mediated increase in total systemic vascular resistance and to an inability to increase heart rate.71 Therefore, elderly persons with hypertension have a greater impairment in baroreflex sensitivity and are more likely to develop orthostatic and postprandial hypotension.

Management of orthostatic and postprandial hypotension in older persons is discussed in detail elsewhere.70 The dose of antihypertensive drug may need to be decreased or another antihypertensive drug given. Older frail persons are most susceptible to orthostatic and postprandial hypotension.70 Measurements of blood pressure in the upright position, especially after eating, are indicated in these persons.70

There was a significantly lower incidence of adequate blood pressure control in older persons with hypertension who had to pay for medications prescribed by their physician.25 This problem needs to be addressed if we are to decrease the great amount of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality caused by inadequate control of hypertension. Many nursing home physicians are reluctant to adequately treat hypertension in their frail patients. Physician education needs to be intensified to provide better medical care of the elderly through the use of optimal doses of drugs found to be effective and safe by evidence-based studies, and therefore recommended by JNC 7 guidelines.26

The author reports no relevant financial relationships.

From the Department of Medicine, Cardiology Division, New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY.

References

1. Aronow WS. What is the appropriate treatment of hypertension in elders? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002;57:M483-M486.

2. Goodwin JS. Embracing complexity: A consideration of hypertension in the very old. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003;58(7):653-658.

3. Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al; HYVET Study Group. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1887-1898. Published Online: March 31, 2008.

4. Aronow WS. Older age should not be a barrier to the treatment of hypertension. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2008;5:514-515. Published Online: July 8, 2008.

5. Aronow WS, Ahn C, Gutstein H. Prevalence and incidence of cardiovascular disease in 1160 older men and 2464 older women in a long-term health care facility. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002;57(1):M45-M46.

6. Mendelson G, Ness J, Aronow WS. Drug treatment of hypertension in older persons in an academic hospital-based geriatrics practice. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:597-599.

7. Joseph J, Koka M, Aronow WS. Prevalence of a hemoglobin A1c less than 7.0%, of a blood pressure less than 130/80 mm Hg, and of a serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol less than100 mg/dL in older patients with diabetes mellitus in an academic nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2008;9:51-54.

8. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group Report on Hypertension in the Elderly. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group. Hypertension 1994;23:275-285.

9. Madhavan S, Ooi WL, Cohen H, Alderman MH. Relation of pulse pressure and blood pressure reduction to the incidence of myocardial infarction. Hypertension 1994;23:395-401.

10. Rigaud A-S, Forette B. Hypertension in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56(4):M217-M225 .

11. Fried LP, Kronmal RA, Newman AB, et al. Risk factors for 5-year mortality in older adults: The Cardiovascular Health Study. JAMA 1998;279:585-592.

12. Aronow WS, Ahn C, Kronzon I, Koenigsberg M. Congestive heart failure, coronary events, and atherothrombotic brain infarction in elderly blacks and whites with systemic hypertension and with and without echocardiographic and electrocardiographic evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Cardiol 1991;67:295-299.

13. Aronow WS, Ahn C. Risk factors for new coronary events in a large cohort of very elderly patients with and without coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 1996;77:864-866.

14. Vokonas PS, Kannel WB. Epidemiology of coronary heart disease in the elderly. In: Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Rich MW, eds. Cardiovascular Disease in the Elderly. 4th ed. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2008:215-241.

15. Aronow WS, Ahn C, Gutstein H. Risk factors for new atherothrombotic brain infarction in 664 older men and 1,488 older women. Am J Cardiol 1996;77:1381-1383.

16. Aronow WS, Frishman WH. Treatment of hypertension and prevention of ischemic stroke. Curr Cardiol Rep 2004;6:124-129.

17. Wolf PA. Cerebrovascular disease in the elderly. In: Tresch DD, Aronow WS, eds. Cardiovascular Disease in the Elderly Patient. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1994:125-147.

18. Aronow WS, Ahn C, Kronzon I. Comparison of incidences of congestive heart failure in older African-Americans, Hispanics, and whites. Am J Cardiol 1999;84:611-612, A9.

19. Levy D, Larson MG, Vasan RS, et al. The progression from hypertension to congestive heart failure. JAMA 1996;275:1557-1562.

20. Stokes J 3rd, Kannel WB, Wolf PA, et al. The relative importance of selected risk factors for various manifestations of cardiovascular disease among men and women from 35 to 64 years old: 30 years of follow-up in the Framingham Study. Circulation 1987;75(6 Pt 2):V65-V73.

21. Aronow WS, Sales FF, Etienne F, Lee NH. Prevalence of peripheral arterial disease and its correlation with risk factors for peripheral arterial disease in elderly patients in a long-term health care facility. Am J Cardiol 1988;62:644-646.

22. Ness J, Aronow WS, Ahn C. Risk factors for symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in older persons in an academic hospital-based geriatrics practice. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48:312-314.

23. Ness J, Aronow WS, Newkirk E, McDanel D. Prevalence of symptomatic peripheral arterial disease, modifiable risk factors, and appropriate use of drugs in the treatment of peripheral arterial disease in older persons seen in a university general medicine clinic. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005;60: 255-257.

24. Aronow WS, Frishman WH. Effect of antihypertensive drug treatment on cognitive function. Clinical Geriatrics 2006;14(11):25-28.

25. Gandelman G, Aronow WS, Varma R. Prevalence of adequate blood pressure control in self-pay or Medicare patients versus Medicaid or private insurance patients with systemic hypertension followed in a university cardiology or general medicine clinic. Am J Cardiol 2004;94:815-816.

26. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 Report [published correction appears in JAMA 2003;290(2):197]. JAMA 2003;289(19):2560-2572. Published Online: May 14, 2003.

27. PROGRESS Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack [published corrections appear in Lancet 2001;358(9292):1556; Lancet 2002;359(9323):2120]. Lancet 2001;358(9287): 1033-1041.

28. Forette F, Seux M-L, Staessen JA, et al; Systolic Hypertension in Europe Investigators. The prevention of dementia with antihypertensive treatment: New evidence from the Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) study [published correction appears in Arch Intern Med 2003;163(2):241]. Arch Intern Med 2002;162(18):2046-2052.

29. Murray MD, Lane KA, Gao S, et al. Preservation of cognitive function with antihypertensive medications: A longitudinal analysis of a community-based sample of African Americans. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:2090-2096.

30. in’t Veld BA, Ruitenberg A, Holman A, et al. Antihypertensive drugs and incidence of dementia: The Rotterdam Study. Neurobiol Aging 2001;22:407-412.

31. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: Principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. HOT Study Group. Lancet 1998;351:1755-1762

32. Koka M, Joseph J, Aronow WS. Adequacy of control of hypertension in an academic nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2007;8:538-540. Published Online: September 17, 2007. 33. Mendelson G, Nassimiha D, Aronow WS. Simultaneous measurements of blood pressures in right and left brachial arteries. Cardiol Rev 2004;12:276-278.

34. Ryan TJ, Antman EM, Brooks NH, et al. 1999 update: ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: Executive Summary and Recommendations: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circulation 1999;100:1016-1030.

35. Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, et al. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators [published corrections appear in N Engl J Med 2000;342(18):1376; N Engl J Med 2000;342(10):748]. N Engl J Med 2000;342(3):145-153.

36. Aronow WS, Ahn C, Kronzon I. Effect of beta blockers alone, of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors alone, and of beta blockers plus angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on new coronary events and on congestive heart failure in older persons with healed myocardial infarcts and asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Am J Cardiol 2001;88:1298-1300.

37. Aronow WS, Ahn C. Effect of beta blockers on incidence of new coronary events in older persons with prior myocardial infarction and diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 2001;87:780-781, A8.

38. Aronow WS, Ahn C. Effect of beta blockers on incidence of new coronary events in older persons with prior myocardial infarction and symptomatic peripheral arterial disease. Am J Cardiol 2001;87:1284-1286.

39. Pahor M, Psaty BM, Alderman MH, et al. Health outcomes associated with calcium antagonists compared with other first-line antihypertensive therapies: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2000:356:1949-1954.

40. Major cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients randomized to doxazosin vs chlorthalidone. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group [published correction appears in JAMA 2002;288(23):2976]. JAMA 2000;283(15):1967-1975.

41. Aronow WS, Ahn C. Incidence of new coronary events in older persons with prior myocardial infarction and systemic hypertension treated with beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, diuretics, calcium antagonists, and alpha blockers. Am J Cardiol 2002;89:1207-1209.

42. Bryson CL, Smith NL, Kuller LH, et al. Risk of congestive heart failure in an elderly population treated with peripheral alpha-1 antagonists. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:1648-1654.

43. Kennedy HL, Brooks MM, Barker AH, et al. Beta-blocker therapy in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial. CAST Investigators. Am J Cardiol 1994;74:674-680.

44. Aronow WS, Ahn C, Mercando AD, et al. Effect of propranolol versus no antiarrhythmic drug on sudden cardiac death, total cardiac death, and total death in patients ≥62 years of age with heart disease, complex ventricular arrhythmias, and left ventricular ejection fraction ≥40%. Am J Cardiol 1994;74:267-270.

45. Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic heart failure: Metoprolol CR/XL Randomised Intervention Trial in Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF). Lancet 1999;353:2001-2007.

46. Aronow WS, Ahn C, Kronzon I. Effect of propranolol versus no propranolol on total mortality plus nonfatal myocardial infarction in older patients with prior myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and left ventricular ejection fraction ≥40% treated with diuretics plus angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Am J Cardiol 1997;80:207-209.

47. Aronow WS, Frishman WH. Angina in the elderly. In: Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Rich MW, eds. Cardiovascular Disease in the Elderly. 4th ed. New York: Informa Healthcare 2008;269-292.

48. Aronow WS, Ahn C, Mercando AD, et al. Decrease in mortality by propranolol in patients with heart disease and complex ventricular arrhythmias is more an anti-ischemic than an antiarrhythmic effect. Am J Cardiol 1994;74:613-615.

49. Aronow WS. Treatment of atrial fibrillation. Part 1. Cardiol Rev 2008;16:181-188.

50. Aronow WS. Treatment of atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter: Part 2. Cardiol Rev 2008;16(5):230-239.

51. Aronow WS. The heart and thyroid disease. In: Gambert SR, ed. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine-Thyroid Disease. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 1995:219-229.

52. Aronow WS. Might losartan reduce sudden cardiac death in diabetic patients with hypertension? Lancet 2003;362:591-592.

53. Carlberg B, Samuelsson O, Lindholm LH. Atenolol in hypertension: Is it a wise choice [published correction appears in Lancet 2005;3665(9460):656]? Lancet 2004;364(9446):1684-1689.

54. Hunt SA, Baker DW, Chin MH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association. ACC/AHA guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: Executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1995 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:2101-2113.

55. Aronow WS. Treatment of heart failure with abnormal left ventricular systolic function in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med 2007;23(1):61-81.

56. Agodoa LY, Appel L, Bakris GL, et al; African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) Study Group. Effect of ramipril versus amlodipine on renal outcomes in hypertensive nephrosclerosis. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;285:2719-2728.

57. Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al; RENAAL Study Investigators. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2001;345:861-869.

58. The ONTARGET Investigators, Yusuf S, Teo KK, Pogue J, et al. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1547-1559. Published Online: March 31, 2008.

59. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CNB, et al; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation 2004;110(6):763]. Circulation 2004;110(2):227-239.

60. Aronow WS. Updated National Cholesterol Education Program III guidelines. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2005;6:160-161.

61. Aronow WS. Managing hyperlipidaemia in the elderly. Special considerations for a population at high risk. Drugs Aging 2006;2:181-189.

62. Koka M, Joseph J, Aronow WS. Prevalence of adequate and of optimal control of serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in an academic nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2007;8:604-606. Published Online: October 22, 2007.

63. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus [published correction appears in Diabetes Care 2003;26(3):972]. Diabetes Care 2003;26 (supplement 1):533-550.

64. Smith SC Jr, Allen J, Blair SN, et al; AHA/ACC; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. ACC/AHA guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 update [published correction appears in Circulation 2006;113(22):e847]. Endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation 2006;113(19):2363-2372.

65. Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): Prospective observational study. BMJ 2000;321:405-412.

66. Ravipati G, Aronow WS, Ahn C, et al. Association of hemoglobin A1c level with the severity of coronary artery disease in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 2006; 97:968-969. Published Online: February 13, 2006.

67. Aronow WS, Ahn C, Weiss MB, Babu S. Relation of hemoglobin A1c levels to severity of peripheral arterial disease in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:1468-1469. Published Online: April 5, 2007.

68. Aronow WS. Q & A with the expert on: Coronary artery disease. Management of an older person with unrecognized Q-wave myocardial infarction detected by a routine electrocardiogram. Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2008;16(6):20-21.

69. Chiong JR, Aronow WS, Khan IA, et al. Secondary hypertension: Current diagnosis and treatment. Int J Cardiol 2008;124:6-21. Published Online: April 25, 2007.

70. Aronow WS. Dizziness and syncope. In: Hazzard WR, Blass JP, Ettinger WH Jr, et al, eds. Principles of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, Companies, Inc; 1998:1519-1534.

71. Gribbin B, Pickering GT, Sleight P, Peto R. Effect of age and high blood pressure on baroreflex sensitivity in man. Circ Res 1971;29:424-431. _________________________________

Counterpoint: Treating Hypertension in the Elderly

Jeanne Y. Wei, MD, PhD

The article by Dr. Aronow1 reviews the benefits associated with the treatment of hypertension in the very elderly (≥ 80 yr) and discusses the findings of the HYpertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET). HYVET is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of active antihypertensive treatment (indapamide 1.5 mg sustained release +/- perindopril 2-4 mg) versus placebo in very healthy, community-dwelling participants over the age of 80 years with a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 160-199 mm Hg during a placebo run-in period plus a diastolic blood pressure of less than 110 mm Hg.

The treatment of the very elderly with a sustained SBP of 160 mm Hg or higher, toward a target blood pressure of 150/80 mm Hg, resulted in a mean blood pressure that was 15.0/6.1 mm Hg lower as compared with that of the placebo group at 2 years. In addition, the antihypertensive treatment resulted in a significant reduction in death due to stroke, all-cause mortality, cardiovascular deaths, and heart failure. The author states that he agrees with the recommendations of the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7), that we should aim to lower blood pressure of the very elderly to less than 140/90 mm Hg, and in very elderly persons with diabetes or chronic renal insufficiency, to lower blood pressure to less than 130/80 mm Hg. However, there are, in fact, no data to support this recommendation of lowering the blood pressure to such a low level in the very elderly (≥ 80 yr).

Other studies have raised the possibility that reducing the SBP to a level that is lower than 140 mm Hg in the very elderly may not be beneficial and that it may be associated with increased mortality.2,3 It is therefore important to note that in the HYVET study, only those very elderly persons with a sustained SBP of 160 mm Hg or higher were treated with antihypertensive therapy, and that in the HYVET study, the target blood pressure of treatment was 150/80 mm Hg, not a blood pressure of less than 130/80 or even 140/80 mm Hg. Another point of note is that although beta-blocker therapy is beneficial in older patients with hypertension and either coronary artery disease (CAD), angina, prior myocardial infarction, peripheral arterial disease, congestive heart failure, and/or arrhythmias, recent studies suggest that beta-blocker treatment in elderly patients with hypertension alone may not be beneficial.4 Therefore, the beta blocker may not be the first drug of choice for those elderly persons with hypertension without either CAD or other cardiovascular disease.

A low dose of a diuretic and, if needed, in combination with an angiotension-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, may be the preferred initial medical regimen for treating the very elderly with hypertension alone. Until further research studies demonstrate that lowering SBP to below 130 mm Hg in those age 80 years and older is beneficial, the target blood pressure for treatment of hypertension in the very elderly (≥ 80 yr) should be considered to be 150/80 mm Hg. In the nursing home, it is especially important to not “over-treat” the very elderly (≥ 80 yr) residents with hypertension, especially because there are many significant comorbid conditions in these patients, including hypotension due to “over-treatment,” orthostatic hypotension and falls, which are extremely common in this group, and which can result in significant morbidity as well as mortality.

We need to remind ourselves of the essence of the Hippocratic Oath: “Do no harm.” Regular monitoring of blood pressure should be performed in those very elderly patients who receive antihypertensive medication, and the medication dosage should be regularly reviewed so as to allow for adjustment of the dosage of antihypertensive medication. In this way, we can help to prevent iatrogenic complications, and also ensure that the lowest dose of the antihypertensive medication that is needed is the dose that is actually used in these very vulnerable individuals.

The author reports no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Wei is Executive Director, Reynolds Institute on Aging, and Chair, Reynolds Department of Geriatrics, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, and Staff Physician, GRECC and Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System, Little Rock, AR.

References

1. Aronow WS. Treating hypertension in the elderly. Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2009;17(6):32-36.

2. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). SHEP Cooperative Research Group. JAMA 1991;265:3255-3264.

3. Gueyffier F, Bulpitt C, Boissel JP et al., Antihypertensive drugs in very old people: a subgroup meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Lancet 1999; 353: 793-796.

4. Bangalore S, Sawhney S, Messerli FH. Relation of beta-blocker-induced heart rate lowering and cardioprotection in hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1482-1489.

Dr. Aronow responds:

Dr. Wei’s comments are excellent. JNC 7 recommends reducing the blood pressure to less than 140/90 mm Hg and to less than 130/80 mm Hg in patients with diabetes mellitus or chronic renal insufficiency.1 The American Diabetes Association recommends reducing the blood pressure to less than 130/80 mm Hg in patients with diabetes mellitus.2 The National Kidney Foundation recommends reducing the blood pressure to less than 130/80 mm Hg in patients with chronic renal insufficiency.3 The American Heart Association recommends reducing the blood pressure to less than 130/80 mm Hg in patients with high-risk coronary artery disease, in patients with stable angina pectoris, in patients with unstable angina pectoris, in patients with non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction (MI), and in patients with ST-segment elevation acute MI.4

The American Heart Association also recommends reducing the blood pressure to less than 120/80 mm Hg in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction.4 In HYVET, the target blood pressure was 150/80 mm Hg.5 We need data on target blood pressure in the elderly.6 Should our target blood pressure for the very elderly be a systolic blood pressure of 150 mm Hg, less than 140 mm Hg, less than 130 mm Hg, or less than 120 mm Hg?6 How low should the diastolic blood pressure be allowed to reach? Further research is needed to answer these questions.

An American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute committee with representatives from numerous professional societies including the American Geriatrics Society, co-chaired by Drs. Carl J. Pepine and Wilbert S. Aronow with the expert assistance of Dr. Jerome L. Fleg, is currently writing guidelines on the treatment of hypertension in the elderly, including the very elderly. These guidelines will contain a section on unanswered questions and future research. Antihypertensive trials should not use the beta blocker atenolol.7,8 In using a beta blocker to treat hypertension in the elderly, I currently use either carvedilol or nebivolol. I completely concur with the comments on the use of antihypertensive drugs in the nursing home patient. Orthostatic hypotension9 and postprandial hypotension10 are common in the frail elderly nursing home patient. One must be aware of the adverse effects caused by antihypertensive drugs in the elderly.11

References

1. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al; National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 Report [published correction appears in JAMA 2003;290(2):197]. JAMA 2003;289(19):2560-2572.

2. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus [published correction appears in Diabetes Care 2003;26(3):972]. Diabetes Care 2003;26(suppl 1):S33-S50.

3. National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002;39(suppl 1):S1-S266.

4. Rosendorff C, Black HR, Cannon CP, et al; American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Treatment of hypertension in the prevention and management of ischemic heart disease. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Epidemiology and Prevention [published correction appears in Circulation 2007;116(5):e121]. Circulation 2007;115(21):2761-2788. Published Online: May 14, 2007.

5. Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1887-1898. Published Online: March 31, 2008.

6. Aronow WS. Older age should not be a barrier to the treatment of hypertension. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 2008;5:514-515. Published Online: July 8, 2008.

7. Aronow WS. Might losartan reduce sudden cardiac death in diabetic patients with hypertension? Lancet 2003;362:591-592.

8. Carlberg B, Samuelsson O, Lindholm LH. Atenolol in hypertension: Is it a wise choice [published correction appears in Lancet 2005;365(9460):656]? Lancet 2004;364(9446):1684-1689.

9. Aronow WS, Lee NH, Sales FF, Etienne F. Prevalence of postural hypotension in elderly patients in a long-term health care facility. Am J Cardiol 1988;62:336.

10. Aronow WS, Ahn C. Postprandial hypotension in 499 elderly persons in a long-term health care facility. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994;42:930-932.

11. Aronow WS. Treating hypertension in older adults: Safety considerations. Drug Saf 2009;32:111-118.