Peripheral Arterial Disease and Its Consequences: Considerations for Long-Term Care

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) in the LTC setting has major consequences in terms of mortality, morbidity, and increased healthcare costs. Complications include pain, chronic skin ulceration, gangrene, amputation, infection, and death. In recent years, medical-legal liability for providers caring for residents with this disease has increased. PAD is complex and involves inflammation and accumulation of lipids in the vascular intima, causing occlusion of blood flow. Chronic occlusive disease causes trophic changes in the extremity that renders skin more fragile and difficult to heal when minor trauma occurs. Noninvasive vascular studies are recommended to establish the diagnosis and quantify amount of occlusion. Management of this disease starts with modification of risk factors. Medications include antiplatelet agents and statins, but their role in healing arterial ulcers is uncertain. Treatment of arterial ulceration consists of wound bed preparation, and chronic skin ulceration related to PAD should be documented in the same manner as pressure ulcers, with care of all chronic wounds in LTC an interdisciplinary function. (Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2009;17[2]:22-26)

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) in the long-term care (LTC) setting has major consequences in terms of morbidity and mortality but is a condition that is often underdiagnosed.1,2 Also known as atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease, complications can include lower-extremity weakness with impaired functional status, increased rate of functional decline, pain, chronic skin ulceration, gangrene, amputation, infection, and death.3-5 PAD results not only in morbidity and mortality, but significantly increases the use of healthcare resources and costs.6 The American Heart Association estimates that as many as 8 million Americans have PAD, and the prevalence based on ankle-brachial blood pressure ratios is approximately 10-20% of community-dwelling individuals age 65 years and older.7,8 Diagnosis is sometimes challenging, and classification of skin ulcers resulting from occlusive arterial disease can be confusing in light of current staging systems and requirements of the Minimum Data Set (MDS). In addition, there is the issue of medical-legal liability when a limb is lost or sepsis is incurred as a result of gangrene or infection.9 This article will provide a basic guide to atherosclerotic occlusive disease of the lower extremity, reviewing diagnostic modalities and highlighting specific challenges in management.

Arterial disease occurs in the setting of risk factors that include diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and smoking. Recently established biochemical risk factors include elevated C-reactive protein and elevated homocysteine levels. Persons who smoke or have diabetes have a higher rate of limb amputation and increased difficulties with wound healing. The old medical term atherosclerosis obliterans is applicable because this disease is generally present elsewhere in the body. Atherosclerosis of arteries of the lower extremity is frequently observed in patients with a history of stroke, multi-infarct dementia, carotid stenosis, coronary artery disease, renovascular hypertensive disease, and thoracic aortic aneurism.10 Risk factor intervention with cessation of smoking and control of blood pressure and diabetes is a major management strategy, but many LTC patients already have advanced, irreversible disease. However, this should not preclude attempts at controlling risk factors and providing suitable pharmacotherapy.

Pathogenesis of Atherosclerotic Disease and Associated Dermal Changes

Atherosclerosis is a disease of vascular endothelium of large- and medium-sized arteries, and is complex and multifactorial in its genesis. Impaired microcirculatory function also occurs, although this is more prominent with vasculopathy accompanying diabetes mellitus.11 Many processes contribute to atherosclerosis, including vascular inflammation with fibroproliferative response, leading to accumulation of lipids, cholesterol, and cellular debris in the intima.12 A heightened inflammatory state indicated by elevated biomarkers such as C-reactive protein may be responsible not only for atherosclerosis of the lower extremities, but also ischemic events in other parts of the vascular tree.13,14 Thrombosis and hemorrhage can exacerbate luminal stenosis and promote distal ischemia. Longstanding atheromas frequently become infiltrated with radio-opaque calcium hydroxyapatite deposits, exacerbating stiffness of the arteries and interfering with the ability to react to vasomotor stimuli and reducing reliability of some diagnostic tests.15

Dermal ulceration due to arterial occlusive disease usually occurs on the foot and distal extremity. Longstanding atherosclerotic disease causes thinning of the skin with anhydrosis, microcirculatory dysfunction with loss of vascular reactivity, loss of hair and sweat glands, and increased fragility.16 Minimal trauma in persons with atherosclerotic disease can precipitate skin damage leading to chronic, nonhealing wounds. Sources of trauma include tight shoes, careless nail clipping, bumping into objects when walking, metal parts of wheelchair footrests, Velcro straps from orthopedic devices, pressure on the toes from tightly tucked sheets, and pressure to the heel or lateral foot while recumbent.

Persons with PAD often have other conditions that add to tissue stress, contributing to nonhealing wounds and/or gangrene. Anemia and hypoxia can increase risk for ulceration through lack of oxygen delivery to tissues. Congestive heart failure or hypotension from inadequate cardiac output or shock will decrease blood flow to the lower extremity. Presence of a catabolic state due to acute illness or decreased nutrient intake adds to the risk for ischemia and skin breakdown, possibly due to hypoalbuminemia with decreased oncotic pressure, resulting in edema. Edema, or fluid in the interstitial space, inhibits passage of nutrients between cells, causing added stress to cells and tissues.

History and Physical Examination

Diagnosis of atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease begins with taking a history of risk factors, as well as symptoms of vascular disease elsewhere in the body. History of operative procedures related to vascular disease of the neck and heart, such as endarterectomy, coronary bypass, or vascular stenting, should be noted. Because of the chronic, longstanding nature of PAD, there may be history of prior vascular procedures to the lower extremity, ulceration, or amputation. Atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease can present with claudication, or exercise-induced ischemia. In severe cases, there may be pain in the extremity at rest.

Persons with decreased activity, such as those who are nonambulatory or bedbound, may not present with intermittent claudication. In addition, residents with cognitive impairment may be unable to express specific complaints needed to direct the clinician to suspect the diagnosis of PAD.17 Comorbidities such as degenerative joint disease may additionally cloud the physical picture, necessitating careful physical examination. The sensory neuropathy of diabetes mellitus may prevent the sensation of pain when tissues become ischemic. As a consequence, atherosclerotic occlusive disease in nursing home residents often presents late, when ischemia to the toes is established and gangrene is setting in. Pain due to tissue ischemia of the lower extremity should be suspected as a cause for agitation in patients with dementia.

The physical examination for PAD begins with observation of the lower extremity for signs that include pallor, cyanosis, edema, atrophy, trophic changes, or cellulitis. Testing for warmth in the joints, crepitus, and sensory function can exclude pain due to degenerative joint disease or sensory neuropathy. Trophic changes of the leg due to atherosclerotic disease include pallor, thickened nails, and shininess of the skin with loss of skin appendages such as hair and sweat glands. Observation is followed by checking pulses, including femoral, popliteal, posterior tibial, and dorsal pedis. A femoral bruit is often predictive of advanced arterial disease. This is followed by palpation of the lower extremity for skin temperature and capillary refill. Due to discoloration, thickening, and chronic disease of the toenail beds in elderly persons, subungual capillary refill may not be an option, and capillary refill of skin of the toes can serve as a reasonable substitute. Normal capillary refill time with good vascularity is less than two seconds.18

Documentation of pulses can have medical-legal implications, as the courts often rely on charting entries for determining whether the standard of care was met for care of skin ulcers.19 Of all the physical findings related to arterial disease, peripheral pulses are most commonly noted in the medical chart—recorded by primary care physicians, surgeons, podiatrists, medical students, and nurses. Problems can arise when examinations are internally inconsistent in the medical record. For example, a hurried clinician can record “peripheral pulses 4+” when other clinicians state that pulses are diminished or absent. If the patient later develops complications related to a leg or foot ulcer resulting in sepsis or amputation, the plaintiff attorney will use the argument that “circulation was adequate by physical examination” or that “clinicians could not agree on presence of vascular disease” to bolster a case for medical malpractice or institutional negligence. Therefore, it is prudent in patients with ulcers of the lower extremity to obtain noninvasive vascular studies to establish the diagnosis and degree of PAD.

Diagnostic Considerations

X-rays of the lower extremity can provide a clue to the extent of atherosclerotic disease when calcification of the vessels is observed. Calcification, however, does not directly indicate stenosis, which is best demonstrated by vascular studies. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended against routine screening for PAD, but diagnostics are indicated once sequelae of this disease are noted.20 There are several types of noninvasive arterial studies, and these include Doppler ultrasound, ankle-brachial index (ABI), segmental pressures, pulse-volume recordings (PVRs), and photoplethysmography.

The term Doppler study is sometimes a source of confusion, as Doppler technology can be applied to different tests. Doppler technology turns blood flow into audible sounds and is used at the bedside to detect pulses when they cannot be palpated, or to take blood pressure when Korotkoff sounds cannot be detected by stethoscope. This is performed by someone trained in using the Doppler transducer and does not yield quantitative information on blood flow. Segmental pressures, discussed below, also utilize the Doppler transducer. More sophisticated Doppler ultrasound technology allows visualization of anatomy of the arterial lumen and is a procedure generally performed in the vascular laboratory. Doppler ultrasonography, magnetic resonance arteriography, and contrast angiography are best reserved for situations when surgical intervention is considered.

ABI is a measure of ankle systolic pressure divided by brachial systolic pressure. A normal ratio is 0.9 to 1.3, and a ratio less than 0.9 indicates a decrease in ankle blood flow relative to the arm. An ABI less than 0.5 indicates severe occlusive disease to the leg. However, this result is less reliable when arteries are stiff, as occurs when calcification is present. This is similar to pseudohypertension, when systolic blood pressure measured with an arm cuff is falsely elevated due to arterial stiffness. It is therefore advisable to use other studies to supplement information obtained by the ABI, including segmental pressures or PVRs.

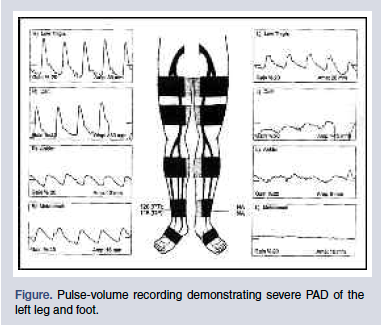

Segmental pressures use inflated blood pressure cuffs and Doppler transducer to measure pressures at various points of the leg. A significant drop in pressure between points indicates atherosclerotic occlusive disease. PVRs are performed by placing inflated cuffs on various parts of the lower extremity, which translate arterial pulsations into wave forms (Figure). Normal wave forms are triphasic and have limited diminution in amplitude, as the cuffs are more distal from the heart. Occlusive PAD is diagnosed when the triphasic wave turns uniphasic, and wave amplitude decreases dramatically at distal locations.

Photoplethysmography is an optical measurement technique applied to evaluation of PAD and is particularly helpful for assessing blood flow to the distal foot. This noninvasive procedure measures flow in the microvasculature, yielding information on blood volume changes and pulsatile waveforms.21 Despite its low cost and ease of use, this technology has not yet received wide acceptance.

Classification and Documentation

The classification of an arterial ulcer is frequently the subject of discussion by nursing home clinicians. Because arterial ulcers can occur over pressure points such as the heel, bunion, or lateral foot, they are often classified as pressure ulcers. If there is clearly diagnosed occlusive arterial disease with ABI less than 0.5, or PVRs showing minimal blood flow to the extremity, one can be comfortable diagnosing the lesion as secondary to PAD.22 Presence of risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, or smoking, along with history of prior vascular events or procedures, makes the diagnosis more secure when challenged by surveyors. Classification of a foot ulcer as secondary to occlusive arterial disease does not relieve the clinician of measures to relieve pressure, such as floating heels, turning and positioning, and the use of protective orthoses.23

Ulcers related to PAD should be followed on wound-tracking sheets along with pressure ulcers. Although lower-extremity vascular ulcers can be of arterial or venous origin, the current version of the MDS 2.0 codes for only “stasis ulcer,” referring to venous etiology.24 Therefore, the diagnosis on the clinician’s documentation and wound-tracking sheet will differ from the diagnosis entered into the MDS. In addition, requirements of the MDS force LTC clinicians to use staging criteria for vascular ulcers, even though these scales were intended only for pressure ulcers. Another quirk of the MDS 2.0 is classification of “eschar.” The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) staging system designates eschar as “unstageable,” but the MDS 2.0 requires eschar to be coded as stage 4.25 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will correct these shortcomings with the next version of the MDS.26

The best way to document atherosclerotic ulceration is with detailed descriptions and measurements, entered into the medical record at least weekly. A physical description will reconcile disparities with MDS entries and help clarify staging discrepancies. Descriptions should go into wound-tracking sheets, as well as narrative documentation in the clinician’s notes. Even if the ulcer is being followed by a wound-care nurse or surgeon, the primary care physician needs to be aware of the wound’s progress and response to treatment, and should address this in the regular required documentation.

Treatment Considerations

Once atherosclerotic occlusive disease is diagnosed in an extremity, care must be taken to avoid tight gauze dressings, provide properly fitting footwear, and avoid compression devices or modalities such as anti-embolism stockings. Exercise therapy is recommended to improve intermittent claudication but may not be an option for nonambulatory residents.

There are several medications available for PAD, including antiplatelet agents and statins.27 Antiplatelet therapies include aspirin and clopidogrel. The Clopidogrel versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischaemic Events (CAPRIE) trial demonstrated that clopidogrel had greater effectiveness in preventing other vascular events, such as stroke and myocardial infarction.28 Statins, along with their lipid-lowering effects, have been found to be of benefit in decreasing inflammation and plaque stabilization.29 Simvastatin in particular has been shown to increase exercise performance and decrease cardiac events.27 Cilostazol is a vasodilator with antiplatelet properties that can decrease claudication, but it is contraindicated in heart failure. Pentoxifylline is a rheologic modulator, also with antiplatelet effects, but it has shown limited benefit for claudication and is not recommended.30 The value of these pharmacologic agents in treating skin ulceration related to occlusive PAD has not been established.

Treatment of chronic skin ulcers related to PAD in LTC settings must be individualized, taking into consideration factors such as functional status, comorbidities, and advance directives. The degree of arterial stenosis can predict wound healing, although experience is necessary to make this judgment. As with pressure ulcers, care of vascular wounds is an interdisciplinary team effort. For residents with limited decision-making capacity, family members and caregivers must be informed of treatment choices and educated as to realistic outcomes. A basic approach starts with routine hygiene and skin care, with lubrication and cleansing of areas between toes. This is followed by management of underlying illnesses, including hypertension, diabetes, and anemia, with optimization of cardiopulmonary status. Persons who smoke should be appropriately counseled, and if a resident can walk, an ambulation program should be implemented. Nutritional assessment is essential, with weight loss and malnutrition properly addressed. When patients have occlusive PAD, avoidance of pressure in the lower extremity is essential even if the resident does not score “at risk” on risk-factor assessment scales.

Procedures to relieve occluded arteries and salvage threatened limbs include intra-arterial thrombolysis, drug-eluting stents, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, and vascular bypass graft. Prior to performing these procedures, the anatomy needs to be defined with Doppler ultrasonography, magnetic resonance angiography, or contrast angiogram. Contrast angiograms have morbidity, including kidney damage and bleeding at the site of catheter insertion. Many nursing home residents may not be candidates for invasive diagnostics and operative vascular procedures due to increased surgical risk. Percutaneous procedures have the advantage of lower morbidity, but long-term patency may be limited.31 Amputation is an alternative consideration when critical limb ischemia is present.

Amputation should be considered if the patient is a poor operative risk, when extensive tissue loss precludes limb salvage, when occlusive disease is advanced and inoperable, when life expectancy is low, or when functional limitations decrease the benefit of limb salvage.5,32 Although amputation is quicker and requires less operative skill, postoperative complications are common and include infection, a nonhealing wound, need for operative revision, and death.33 Loss of a limb is also alarming to residents and their families, who may need counseling to accept this outcome. Consultation with a vascular surgeon is recommended to assist with informed management decisions, particularly when there is rest pain, a nonhealing ulcer, or impending gangrene.

Proper wound-bed preparation is the mainstay of local care for the vascular ulcer, as well as other types of ulcers of the lower extremity. Wound-bed preparation is the process of encouraging granulation and epithelialization at both the base of the wound and the wound margin.34 This begins with removal of necrotic debris and slough with enzymatic, mechanical, or surgical debridement. Research has revealed the importance of bacterial biofilms—matrix-enclosed, adherent microscopic layers of organisms that inhibit phagocytosis and other aspects of healing.35 Biofilms can be disrupted and bacterial balance optimized with topical antibiotics or silver-containing dressings.36 Impregnated gauze comes in different forms, including hydrogel and oil-based, depending upon specific needs of the wound bed. Povidone-iodine and peroxide are discouraged due to damage to delicate new epithelial and granulation tissue. Occlusive dressings may assist wound healing by encouraging a moist wound environment. Large wounds may be amenable to grafting, of which there are several types including biological membranes, cadaver grafts, or autologous skin.

Negative pressure therapy is relatively new and has received wide acceptance in treating complex wounds, including those related to PAD. This modality is expensive, and there are limited data to support its use over other, more traditional wound care modalities.37

Summary and Conclusions

PAD in the LTC setting has extensive consequences and is underdiagnosed. Clinicians must understand the technologies to diagnose and quantify this common disease in order to provide proper management and to proactively anticipate medical-legal consequences of tissue ischemia. Treating persons with PAD is an interdisciplinary function and involves physicians, social workers, nurses, rehabilitation therapists, nutritionists, and surgical specialists. Care and documentation of chronic wounds related to PAD is complex and should be integrated into the daily work-flow. Everyone in the LTC setting must understand the importance of proactive, quality-oriented care of residents with occlusive atherosclerotic disease of the lower extremity.

The author reports no relevant financial relationships.

Author Affiliations:

Dr. Levine is Associate Clinical Professor of Medicine at New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY, and attending physician at St. Vincent’s Hospital and Medical Center’s Geriatrics Division and Wound Care Center, New York, NY.