Palliative Care in LTC: Essentials of Pain Management

This article is the fourth in a series on palliative care in the LTC setting. Part I appeared in the April issue, Part II appeared in the May issue, and Part III appeared in the July issue of the Journal.

The high prevalence of painful conditions in residents in the LTC continuum can result in major losses in resident quality of life and dignity. Those with advanced life-threatening illness require timely, effective, and safe management of their total pain. The undertreatment of pain can result in decreased functionality, depression, and poor sleep. Effective pain management requires a thorough interdisciplinary assessment guided by excellent practitioner and nurse skills, a sound knowledge base, and a conducive attitude—all provided within the context of the federal and state regulatory environment in LTC and each practitioner’s scope of practice. Scheduled low-dose opioids are considered the foundation to the treatment of chronic persistent pain of moderate severity in LTC residents. Acetaminophen should be considered as initial treatment for musculoskeletal pain, while any nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug should be prescribed for only a brief period. Use of adjuvant analgesics as well as nonpharmacologic and complementary and alternative medicine treatments can further optimize the treatment of pain. (Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2010;18[9]:28-35)

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The high prevalence of conditions that cause either acute and/or persistent pain in residents in the long-term care (LTC) setting challenges practitioners to effectively manage pain. Up to 80% of residents have a condition that is associated with either intermittent or constant pain.1

Successful pain management and palliation of nonpain symptoms in this patient population (whether on hospice or not) is challenging to practitioners and must be integrated into the treatment of multiple and complex interacting medical and psychosocial conditions in patients who also commonly have a high prevalence of cognitive impairment, functional dependency, and are receiving a high number of prescription medications. All of these factors require practitioners to become knowledgeable in pain management and the total care of all patients who reside in skilled nursing and residential/assisted living facilities, especially for those patients with advanced life-threatening illness or who are on hospice.

Effective pain management requires timely recognition, a comprehensive and interdisciplinary assessment, an appropriate treatment plan, and monitoring of treatment outcomes. The emergence of pain or a painful condition should be anticipated and, if possible, prevented. Treatment of pain should be consistent with the patient’s values, preferences, and goals of care, and provided within the context of healthcare ethics and state and federal law.

Pain and Associated Sequelae

The International Association for the Study of Pain has defined pain as an “unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.”2 All pain should be assessed as to the four components of total pain: physical, psychoemotional, social, and spiritual3; assessment also includes determining whether the pain is nociceptive, neuropathic, or inflammatory. Goals of pain treatment are listed in Table I.

The International Association for the Study of Pain has defined pain as an “unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.”2 All pain should be assessed as to the four components of total pain: physical, psychoemotional, social, and spiritual3; assessment also includes determining whether the pain is nociceptive, neuropathic, or inflammatory. Goals of pain treatment are listed in Table I.

In older adults with pain, the experience of loneliness, depression, and sleeplessness can further diminish their sense of well-being.4 Successful treatment of pain in LTC includes treatment of these interdependent comorbidities.

Common and Less Common Causes of Pain

Low-back pain, arthritic conditions, previous fractures, and neuropathies have accounted for 40%, 37%, 14%, and 11%, respectively, of conditions that cause pain in residents of nursing facilities.5 Less common conditions include leg cramps, headache, claudication, cervical or lumbar spinal stenosis, crystal-induced arthropathies (eg, gout, pseudogout), polymyalgia rheumatica, osteoporosis (eg, a vertebral compression fracture), oral and dental conditions, fibromyalgia, soft-tissue injury (eg, abrasions, skin tears, pressure ulcers), and neuropathies (eg, diabetic peripheral neuropathy, trigeminal neuropathy, pre-eruptive and postherpetic neuralgia). Pain can also be associated with gastrointestinal (GI) conditions such as constipation, fecal impaction, ileus, gastritis, gastroesophageal reflux and diverticulitis, and urinary conditions such as infection, bladder distention, and kidney/bladder stones. Cancer pain occurs in no more than 3% of residents in nursing facilities.5 Accurate diagnosis as to the cause of a person’s pain is essential to determining the most appropriate and effective treatments.

Pain Assessment

Practitioners and facility staff must initiate a comprehensive and multidimensional pain assessment. The overarching requisites of pain assessment in residents in LTC include: (1) determining the presence, cause(s), and types of pain being experienced by the resident; (2) identifying comorbidities that may exacerbate the pain; (3) reviewing the residents’ beliefs, attitudes, and expectations regarding pain and its treatment; and (4) establishing an individualized treatment plan for the pain.6

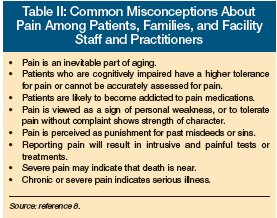

The self-report of pain can be hindered by misconceptions about pain among patients and staff (Table II), cognitive impairment, communication disorders (eg, aphasia), mood disorders (eg, depression), as well as cultural and ethnic background.

The self-report of pain can be hindered by misconceptions about pain among patients and staff (Table II), cognitive impairment, communication disorders (eg, aphasia), mood disorders (eg, depression), as well as cultural and ethnic background.

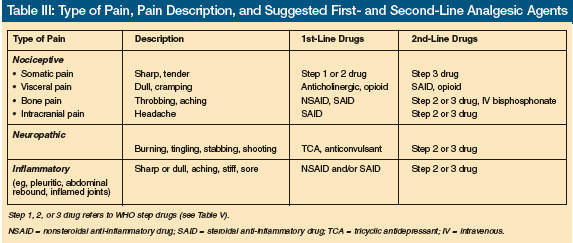

The characterization of pain includes a description of its location, onset, duration, frequency, intensity, and any exacerbating or alleviating factors. Pain descriptors may help practitioners identify whether the pain is more likely to be nociceptive, neuropathic, or inflammatory in origin (Table III). Associated symptoms such as weight loss or fever may indicate an underlying malignancy or infection. Other relevant symptoms should be determined through a comprehensive review of symptoms, as well as past and current treatment modalities including the use of nonpharmacologic, pharmacologic, and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM).

It is also helpful to classify each pain symptom as to whether it is acute, chronic (ie, ≥ 1 mo in duration), intermittent, positional, or iatrogenic. Disturbance or incident pain is activity-related, while breakthrough pain (BTP) is pain that acutely occurs superimposed on controlled chronic pain.

Pain Assessment Tools

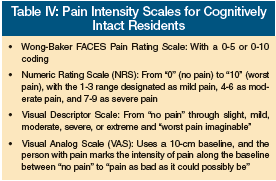

Nonspecific signs and symptoms of pain include loss of physical function, self-imposed immobility, resisting care, rubbing, fidgeting, grimacing, agitation, eating or sleeping poorly, crying, groaning, or breathing heavily.7 Such behaviors may indicate pain in residents who may or may not be poorly communicative or have dementia. Examples of pain scales that objectively measure pain in such patients are included in Appendix 1 of the American Medical Directors Association (AMDA) Clinical Practice Guideline on Pain Management in the Long-Term Care Setting (2009 edition).8 In LTC residents who are cognitively intact, pain intensity scales that are commonly used are listed in Table IV.

Nonspecific signs and symptoms of pain include loss of physical function, self-imposed immobility, resisting care, rubbing, fidgeting, grimacing, agitation, eating or sleeping poorly, crying, groaning, or breathing heavily.7 Such behaviors may indicate pain in residents who may or may not be poorly communicative or have dementia. Examples of pain scales that objectively measure pain in such patients are included in Appendix 1 of the American Medical Directors Association (AMDA) Clinical Practice Guideline on Pain Management in the Long-Term Care Setting (2009 edition).8 In LTC residents who are cognitively intact, pain intensity scales that are commonly used are listed in Table IV.

Multidimensional pain scales such as the McGill Pain Questionnaire9 and the Brief Pain Inventory assess the effect of pain on mood and function. These two scales would be more appropriate to use in residents at residential care and assisted living facilities.

Practitioners in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) should regularly review each resident’s most recent Minimum Data Set (MDS) Section J on HEALTH CONDITIONS. Its newer version, MDS 3.0, will go into effect October 1, 2010, and the subsections on pain assessment and management (J0100 to J0850) are much more structured and extensive. It now involves a Pain Assessment Interview and use of the Numeric Rating Scale and the Verbal Descriptor Scale with a 5-day look back. The MDS is not used in residential care or assisted living.

Physical Exam

A focused physical exam should be performed that is directed both by the resident’s past and current medical conditions and the pain history. Careful observation of signs and symptoms may elucidate the pathophysiology and etiology underlying the pain, which in turn will help guide the most appropriate treatment(s) to alleviate the pain.

Important aspects of the physical exam include: vital signs (eg, increased respiratory/heart or blood pressure); general appearance (eg, affect, body positioning); body/limb movements (ie, restlessness) or lack of movement (ie, guarding, immobility); a focus on the musculoskeletal and neurological systems; observation of physical function; ability to reproduce and/or worsen the pain through palpation or manipulation of limbs or body; and careful attention to other organ systems such as skin, respiratory, cardiac, GI, and urinary.

Nociceptive “somatic” pain typically intensifies with palpation to a specific area. Nociceptive “visceral” pain can include generalized discomfort to palpation of the abdomen. Inflammatory pain is aggravated by deep breathing (ie, pleuritic pain) or rebound tenderness of the abdomen (ie, peritonitis). Neuropathic pain can be characterized by allodynia (in which an ordinary nonpainful stimulus evokes pain); hyperalgesia (an exaggerated pain response to a nonpainful or mildly painful stimulus); and skin atrophy, loss of hair, muscle group weakness, and numbness.

Interdisciplinary Assessment

Input of the interdisciplinary team is essential for the proper assessment and management of pain. Nurses should be adept in obtaining a pain history and performing a limited physical examination, be familiar with the use of a pain assessment tool(s), and be able to articulately report their assessment to practitioners. Nurse aides should be attuned to pain or discomfort that occurs during provision of personal care to residents. Other members of the healthcare team can assess the psychological, psychiatric, social, spiritual/religious, and cultural aspects of residents’ pain and suffering.

Pain Treatment

Treating Pain Within the Regulatory Environment

The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) related to SNFs specifically states that “each resident must receive and the facility must provide the necessary care and services to attain or maintain the highest practicable physical, mental, and psychosocial well-being in accordance with the comprehensive assessment and plan of care” (42 CFR 483.30 Nursing services). An integral part of the quality-of-care assessment done by state and federal surveyors (F Tag 309) is the review of facility residents who either have pain symptoms, are being treated for pain, or who have the potential for pain symptoms related to a medical condition or treatment. Thus, practitioners have a crucial responsibility to ensure early recognition and effective management of pain in order to ensure that all residents attain the highest practicable level of well-being.

The adequacy of pain management is one of several publically reported performance measures for SNFs. This information is available at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) website that can be accessed at www.medicare.gov/nhcompare. Note that physicians and SNFs are at increased liability for negligence and elder abuse when pain is undertreated.10

Pharmacologic Treatment of Pain

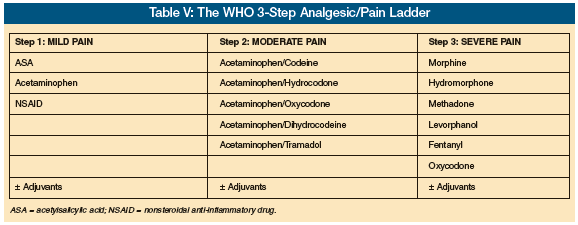

In LTC, pain is optimally managed by: (1) determining, if possible, the pathophysiology and etiology underlying the pain; (2) utilizing an interdisciplinary assessment and treatment; (3) being knowledgeable in the prescribing of analgesics; (4) balancing nonpharmacologic with pharmacologic treatments; and (5) meeting residents’ goals of treatment for their pain. The mainstay to effective pain management is prescribing analgesics according to type of pain and pain intensity (Tables III and V, respectively). Accordingly, first determine the type of pain the resident is experiencing. Secondconsider whether a first- or second-line analgesic would be appropriate or not, dependent upon the resident’s diagnosis, comorbidities, and the analgesic’s mode of pharmacologic action and potential adverse effects and toxicities. And finally, choose the class of analgesic medication based on the three-step World Health Organization (WHO) pain ladder as follows:

• For mild pain: Prescribe (start with) a nonopioid (eg, acetaminophen) for long- term use and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) for short-term use.

• For moderate pain: Prescribe a mixed opioid(eg, acetaminophen combined with oxycodone or hydrocodone).

• For severe pain: Prescribe a pure opioid (eg, morphine, oxycodone, hydromorphone, fentanyl).

If pain is persistent or increasing in severity, consider: (1) increasing the dose of the analgesic being used; (2) changing or adding a second-line analgesic; (3) advancing to the next step of the analgesia ladder; (4) adding an adjuvant analgesic; (5) using nonpharmacologic and CAM therapies; (6) addressing total pain; and (7) treating coexisting anxiety, depression, and insomnia. In some circumstances, several of these options may be appropriate.

----------

Case Study

An elderly SNF resident with known spinal metastases, receiving scheduled doses of acetaminophen-hydrocodone every 4 hours, has had persistent though increasing severe low-back pain and now has onset of burning pain radiating into both lower extremities. Treatment options to consider include any or all of the following:

• Increasing the dose of the mixed opioid is probably not warranted, as this would likely exceed the recommended daily dose of acetaminophen (4000 mg/day). Due to increased risk of hepatoxicity with old age and poor nutritional status, not exceeding 2000-3000 mg daily would be prudent.

• For severe and increasing nociceptive pain: Change the mixed opioid to a pure opioid, perhaps morphine or oxycodone.

• For bone pain: Start a NSAID and/or corticosteroid.

• For neuropathic pain: Consider adding an anticonvulsant (eg, gabapentin).

• Nonpharmacologic treatment: Consider application of heat or ice to the lower back; ensure a proper pressure-relieving mattress and proper body positioning in bed and when sitting, if able to do so.

• CAM therapies: Use massage or guided imagery, for example.

• Address emotional, social, and spiritual aspects of pain (ie, components of total pain).

• Consider prescribing an antidepressant medication.

----------

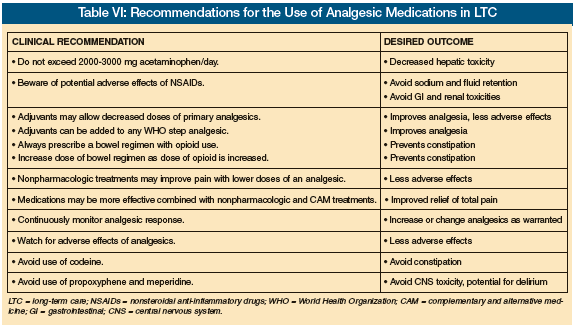

Some clinical recommendations for the management of pain with analgesics in the LTC setting are summarized in Table VI. Excellent resources on the management of pain in the LTC setting8 and persistent pain in adults11 have been published in 2009, along with an update of the American Geriatrics Society AGS Clinical Practice Guideline: Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons.12 The latter reference provides guidelines according to both quality of evidence (low-moderate-high) and degree of recommendation (weak or strong). Several of its recent recommendations are now in better accordance with the AMDA Clinical Practice Guideline: Pain Management.8 Notable AGS recommendations applicable to LTC include:

• Acetaminophen should be considered as initial and ongoing treatment of persistent musculoskeletal pain. Use with caution in those with hepatic insufficiency and chronic alcohol abuse. Avoid use in liver failure.

• Nonselective NSAIDs (ie, cyclooxygenase-1 [COX-1] and COX-2 inhibiters) and COX-2 selective inhibiters (eg, celecoxib) should be prescribed with caution, and only then for a short period of time, a few weeks at the most. GI complications can be partially reduced with addition of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). Avoid use in active peptic ulcer disease, and use with caution in heart failure, hypertension, and concomitant use of corticosteroids and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Patients using aspirin for cardioprophylaxis should not use ibuprofen, while those using a selective COX-2 inhibitor and aspirin should be placed on a PPI.

• Patients with moderate-to-severe pain on a daily basis should be considered for scheduled “around-the-clock” doses of an opioid with as-needed doses of the same opioid for BTP.

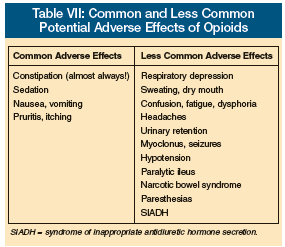

• Anticipate, assess for, and identify potential opioid-associated adverse effects (Table VII).

• Tertiary tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, imipramine, doxepin) should be avoided because of the high risk for anticholinergic effects, impaired cognition, and confusion. • Long-term use of corticosteroids should be reserved for patients with inflammatory pain or metastatic bone pain.

• In patients with neuropathic pain, consider adjuvant analgesics; if the neuropathic pain is localized, consider a topical lidocaine patch (applied once/day, “on” for 12 h and “off” for 12 h; maximum 3 patches/day)

• Methadone should be prescribed and cautiously titrated only by practitioners familiar with its use and risks. Consult a pain specialist, hospice medical director, or palliative medicine clinician.

General guidelines for prescribing any analgesic include cautious and regular monitoring of patients for attainment of its desired therapeutic effects for pain relief, adverse effects, and safety. Beware that the use of multiple analgesics can potentially perpetuate or worsen polypharmacy and its sequelae. Analgesic therapy should begin with the lowest possible effective dose and be increased slowly based on response (ie, degree of analgesia, side effects). Remember that some drugs can have a delayed onset of action, and thus their therapeutic benefit or adverse effects may be slow to occur. An adequate therapeutic trial should be administered before it is deemed ineffective and prematurely discontinued. Both adjuvant analgesics and nonpharmacologic treatments may result in analgesics being more effective, often at lower doses, which can then diminish the potential for adverse effects.

Use of Adjuvant Drugs. Several classes of drugs not usually considered as analgesics are referred to as adjuvant analgesics because they may effectively relieve certain types of pain (ie, neuropathic, bone, inflammatory pain), which may only partially respond to an opioid. Adjuvant drugs include NSAIDs, corticosteroids, antidepressants, anticonvulsants (eg, gabapentin, pregabalin, valproic acid), and topical agents such as the lidocaine patch, capsaicin, menthol, and diclofenac gel. Practitioners should refer to references 3, 8, and 11 for more thorough reviews on the use of adjuvant analgesics. Bisphosphonates, calcitonin, and radioisotopes are adjuvants to consider in severe or recalcitrant bone pain.3

Essentials of Opioid Therapy. When prescribing an opioid, several precautions should be followed to ensure their effective and safe use8:

• Use an opioid to treat moderate-to-severe acute and chronic pain that is not relieved by other classes of analgesics.

• Use an opioid to treat moderate-to-severe acute and chronic pain that is not relieved by other classes of analgesics.

• Anticipate adverse effects (Table VII).

• Always prescribe a bowel regimen to prevent constipation, and titrate up its dose as the dose of the opioid is increased.

• Remember that pure opioids have no maximum effective analgesic dose or “ceiling effect,” so the dose can be increased until the desired analgesic effect is achieved or until side effects become intolerable.

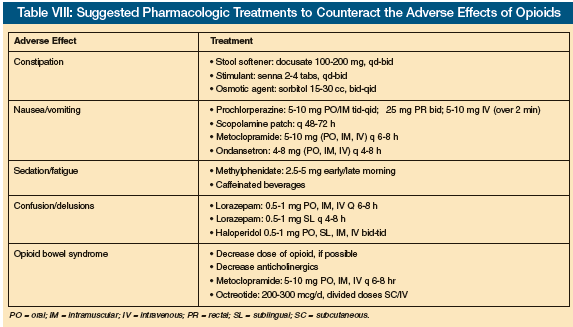

• Other pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments may need to be used to treat adverse effects of an opioid, rather than decreasing the dose of the opioid and subsequently losing adequate analgesia (Table VIII).

• “Start low and go slow,” especially in opioid-naïve patients (usually 2-5 mg every 3-4 h) of immediate-release oral morphine or its equivalent.

• Start with an immediate-release oral opioid, and once the total daily dose needed to control the patient’s pain is achieved, convert to the equivalent dose of a sustained-release formulation. Starting with a sustained-release opioid for moderate chronic pain may be effective in some patients.

• For chronic pain, follow the WHO guidelines of administrating the opioid by mouth, around-the-clock for continuous pain, according to the analgesic 3-Step ladder, tailored to the individual and with attention to detail and use of adjuvant therapy.

• For BTP, administer 10-15% of the total daily opioid dose every 1-2 hours for severe pain or 3-4 hours for moderate pain. Usually, the daily dose of an opioid can be safely increased 25-50% for mild-to-moderate pain, and 50-100% for moderate-to-severe pain. However, closely monitor for potential acute and delayed adverse effects to the opioid.

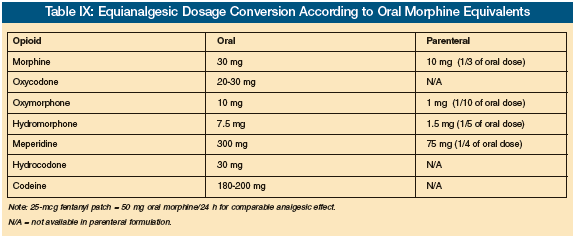

Some special considerations on opioid use are as follows: When patients experience intolerable adverse effects to an opioid or have persistent pain despite escalating doses of the opioid, consider converting/rotating to another opioid. For example, a patient experiencing intolerable nausea due to morphine may not with oxycodone or hydromorphone. A dosage equianalgesic conversion table (Table IX) can serve as a general guide to ensure safe conversion from one opioid to another while decreasing the risk of underdosing (with loss of adequate analgesia) or overdosing (with increased adverse effects). When converting, it is prudent to use only 50-75% of the “calculated” converted dose to guard against an excessive dose of the opioid, and then titrate up the dose depending on its analgesic effect.

Other situations that may warrant conversion or rotation to another opioid include the following:

• The dose of a mixed opioid such as hydrocodone or oxycodone with acetaminophen cannot be increased because it would exceed the recommended daily amount of acetaminophen.

• Progressive liver disease: The morphine or codeine dose needs to be reduced due to decreased clearance and increased risk of toxicity. The fentanyl patch does not require a dose adjustment in liver disease, although its absorption and effectiveness will be greatly diminished if the patient is cachectic with insufficient subcutaneous fat tissue to allow effective transdermal absorption.

• Renal failure or dialysis: Morphine and codeine should not be used if the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is less than 30 mL/minute or on dialysis. Cautiously use oxycodone or hydromorphone when the GFR is 30-50 mL/minute. Methadone and fentanyl are safe to use in renal failure, but note that neither is dialyzable, so either drug should be cautiously titrated.

• Past or current opioid addiction: It may be difficult to discern drug-seeking behavior from legitimate need for an increase in the dose of the opioid for uncontrolled pain. If diversion of the opioid is suspected, methadone should be considered, but it must be diligently prescribed and cautiously monitored for analgesic response and toxicity. Use only for treatment of chronic pain, NOT acute or BTP.

• Last hours and days of living: Progressive prerenal and renal failure may result in accumulation of morphine metabolites, and thus increased adverse effects.

Meperidine and propoxyphene should be avoided because either may precipitate confusion and seizures. Their metabolites, normeperidine and norpropoxyphene, will accumulate with decreased renal function. Pentazocine, an opioid agonist-antagonist, has a high incidence of agitation and hallucinations, and can inhibit the analgesic effect of morphine and other pure agonist opioids.

Remember that opioids can cause hyperesthesia or an increased sensitivity to stimulation, such as touch or movement. In these circumstances, the opioid dose should be decreased or converted to another.

An opioid-induced delirium is not uncommon, especially during the last days of life. Here, either the dose of the opioid can be decreased if still able to maintain adequate analgesia, or the opioid dose can be maintained with the addition of low doses of a benzodiazepine (eg, lorazepam) and/or an antipsychotic such as haloperidol or risperidone, either of which can be administered sublingually.

In palliative care, opioids are considered first-line pharmacologic agents for the management of dyspnea in patients with advanced, life-threatening illness. Their use for relief of dyspnea is discussed in another article in this series on palliative care in LTC.13

The use of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is beyond the scope of this article. Refer to reference 3 for further information on PCA. Rarely would PCA be required in the LTC setting, as other routes of administration of opioids are usually effective (oral, sublingual, per rectum, or transdermal).

When patients are no longer able to swallow, a concentrated solution of either morphine or oxycodone (20 mg/cc) can be administered sublingually or transbuccally. If a patient cannot tolerate oral administration of the opioid, consider giving slow-release morphine or oxycodone tablets rectally. Remember that some formulations of morphine can be administered through a PEG tube by opening the capsule and flushing its contents of microbeads down the tube. Sustained-release morphine or oxycodone should never be crushed in order to administer it.

Methadone can be very effective in treating severe nociceptive and neuropathic pain. However, its prolonged and variable metabolism and complex drug-drug interactions can result in life-threatening arrhythmias and death (as any opioid can). Thus, it should only be prescribed by (or in consultation with) a practitioner with experience and expertise in its use. For further information, refer to reference 8 (Appendix 6) and reference 3.

Improving Pain Care in LTC

CMS, state regulatory agencies, and practitioners in LTC have recognized that improving pain assessment and management in all residents in LTC is a high priority. A recent literature review on improving the process of pain care in nursing facilities reported that successful pain care requires a pain process improvement framework throughout the nursing facility, use of clinical decision-making algorithms, an interdisciplinary approach, continuous evaluation of outcomes, and use of on-site “resource” consultants.14 AMDA has compiled an excellent educational LTC Information Tool Kit on Palliative Care in the Long-Term Care Setting that can guide practitioners and the interdisciplinary team on the implementation of quality assurance and improvement initiatives in palliative and end-of-life care.15

Summary and Conclusions

Undiagnosed and inadequately treated pain in residents in the LTC setting can result in unintended adverse patient and facility outcomes. Practitioners must recognize and overcome the patient and system barriers to the underrecognition and undertreatment of pain. To not do so can put practitioners and LTC facilities at risk for neglect and elder abuse, put the facility at risk for citations by surveyors for deficient quality of care, and risk poor performance on pain measures that are publically reported at the CMS and state websites.

Effective palliation of pain and nonpain symptoms must be considered an integral component alongside the traditional treatment of disease in all LTC residents where disease-modifying treatments are not necessarily forgone if appropriate and congruent with the residents’ goals of care.

Acknowledgment Dr. Winn teaches the Palliative Care Curriculum and the Certified Medical Director course for the American Medical Directors Association. The author reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Winn is Professor of Family Medicine, University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City.

References

1. Ferrell BA, Ferrell BR, Osterweil D. Pain in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc 1990;38:409-414.

2. Part III: Pain terms, a current list with definitions and notes on usage. In: Merskey H, Bogduk N. eds. Classification of Chronic Pain. 2nd ed. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 1994:209-214.

3. Storey CP, Levine S, Shega JW, eds. Assessment and Treatment of Physical Pain Associated with Life-Limiting Illness. UNIPAC Three. 3rd ed. Glenview IL; American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; 2008.

4. Deane G, Smith HS. Overview of pain management in older persons. Clin Geriatric Med 2008;24(2):185-201, v.

5. Stein WM, Ferrell BA. Pain in the nursing home. Clin Geriatr Med 1996 12:601-613.

6. Bruckenthal P. Assessment of pain in the elderly adult. Clin Geriatr Med 2008;24(2):213-236, v-vi.

7. Hurley AC, Volicer BJ. Hanrahan PA, et al. Assessment of discomfort in advanced Alzheimer patients. Res Nurs Health 1992;15(5):369-377.

8. American Medical Directors Association. Clinical Practice Guideline: Pain Management. Columbia, MD: AMDA; 2009.

9. Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: Major properties and scoring methods. Pain 1975;1(3):277-299.

10. Warm EJ, Weissman DE. #63 The legal liability of under-treatment of pain, 2nd ed. Medical College of Wisconsin. Accessed August 9, 2010.

11. Fine PG, Herr KA. Pharmacologic management of persistent pain in older persons. Clinical Geriatrics 2009;17(4):25-32.

12. American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. AGS Clinical Practice Guideline: Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57(8):1331-1346. Published Online: July 2, 2009.

13. Smucker WD. Palliative and end-of-life care in LTC: Evaluation and treatment of dyspnea, death rattle, and myoclonus. Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2010;18(5):37-41.

14. Swafford KL, Miller LL, Tsai P, et al. Improving the process of pain care in nursing homes: A literature synthesis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:1080-1087.

15. LTC Physician Information Tool Kit. Palliative Care in the Long-Term Care Setting. Columbia, MD: AMDA; 2007.