Palliative and End-of-Life Care in LTC: Practical Implications of Understanding Spirituality and Religion

This article is the third in a series on palliative care in the LTC setting. Part I appeared in the April issue, and Part II appeared in the May issue of the Journal. Part IV will appear in the September issue of the Journal.

Spirituality and religion have been intertwined with medical care throughout history. In the past few decades, increasing emphasis has been placed on the interaction of patients’ belief systems and impact on their physical and mental health. Tools to access spirituality, religious beliefs, and value systems have been developed to help physicians integrate these domains into the realm of medical care. A Consensus Conference sponsored by the Archstone Foundation recently published a report with recommendations for integrating spiritual care and improving palliative care. This brief review offers a step-wise implementation of these recommendations in long-term care. (Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2010;18[7]:28-31).

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

There was a time in history when medicine and spirituality were one. Before science could help us explain and address illness, our ancestors turned to religion or spirituality for the ultimate answers. Despite the many scientific advances, there remain many unanswerable questions. Physicians are left with the query, “What role does religion and spirituality play in my practice of medicine?”

The accepted definition of spirituality is the personal search for meaning, purpose, and truth in one’s life, while religion is the organized set of beliefs and values one practices.1-4 If one accepts the premise that all long-term care (LTC) is palliative care, whether there is a designation of terminal illness or not, then spirituality and religion are not just the awakened or intensified concerns of end of life, but a dynamic aspect of everyday life of all patients.5

As we age, the meaning or purpose of one’s life takes on developmental importance. Erik Erikson described that in late life one must review life and balance between Integrity and Despair.6 From this balance springs the developmental strength of Wisdom. A physician is in a unique position to foster this developmental strength as the patient identifies meaning, purpose, and intrinsic supports available.

The literature has supported that religious beliefs are important to aging individuals, and to medical care in general.7-10 There are case reports of intense belief systems and seemingly miraculous cures.11 Studies have determined that psychological well-being and depression associated with medical illness may be affected by intrinsic religious beliefs.12,13 Recent studies continue to demonstrate the importance of religious beliefs in nursing home residents.14,15

Physicians have been given guidance in spiritual care in medicine, to understand why spirituality is important16 and to address the need for initiating the conversation of spirituality at the end of life.17,18 There is increasing regulatory influence recognizing the importance of assessments.19 To place this in context in this age of expediency, does spirituality and religion need to be included in physicians’ history-taking? As physicians are urged to view pain as a vital sign, are spirituality/religious beliefs also a vital sign?

The lay literature has addressed the growing interest in religion and spirituality. A Time magazine article discussed at length the “biology of belief” and described the study of religion and medicine as a “growth market.”20 A forum of two physicians and a well-known academic hospital chaplain debated the role of the physician in obtaining or using a spiritual history.21 When is it appropriate for the physician to use one of the many spiritual history tools? Who is the correct person to complete the spiritual history? The debate concluded with the agreement that important basic screening questions were recommended to be completed by the physician. In the course of the debate, Dr. Andrew Newberg mused, “I’ll be idealistic for a moment. I would love to see the practice of medicine be a team event.” Unknowingly, Dr. Newberg is describing the day-to-day functioning of the LTC setting. Even though the LTC setting represents an interdisciplinary team, how can the team physician do a better job of integrating the patient’s nonmedical needs—specifically religion and spirituality—into a medical treatment plan?

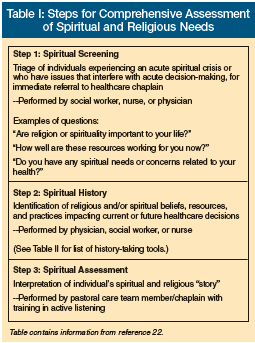

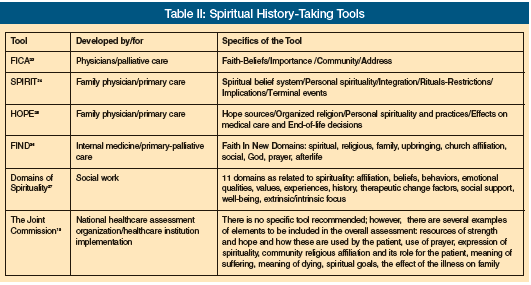

The Journal of Palliative Medicine published the proceedings of a consensus conference seeking to improve the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care.22 The consensus panel pointed out that by not adequately assessing religious or spiritual needs, a comprehensive care plan of the individual cannot be developed. The panel differentiated a spiritual screening, a spiritual history, and a spiritual assessment into three distinct steps (Table I).22 (Table II lists several useful spiritual history-taking tools available to clinicians.19,23-27)

The Journal of Palliative Medicine published the proceedings of a consensus conference seeking to improve the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care.22 The consensus panel pointed out that by not adequately assessing religious or spiritual needs, a comprehensive care plan of the individual cannot be developed. The panel differentiated a spiritual screening, a spiritual history, and a spiritual assessment into three distinct steps (Table I).22 (Table II lists several useful spiritual history-taking tools available to clinicians.19,23-27)

Once all of this information is gathered, how is this information used by the team? It is the basic aspect of the patient’s ability to rally coping strategies, reconcile values with medical expectations/realities, and incorporate traditions and rituals into healthcare. For the physician, recognizing the importance of religious and spiritual issues will help the practitioner avoid the pitfalls associated with discussing religious and spiritual issues.17 To be able to use the information gathered during the spiritual screening or history, how much does the physician have to know and understand about his/her own spirituality and religious beliefs? The LTC physician has an advantage over the individual practitioner in a more isolated office. The team in the LTC environment provides a sounding board for ethical/value discourse. Respecting a patient’s value system also requires that the physician respect his/her own beliefs.

Given the current level of knowledge of the importance and impact of spirituality in medical care, and the recommendations of the consensus report, the LTC physician can do the following to improve patient care:

1. Incorporate into the history and physical some basic questions concerning the patient’s spirituality pertinent to the patient’s medical decision-making, such as, “How would you like me to address your spiritual/religious/cultural needs in your medical care?” This question will elicit responses from those residents who have religious practices that prohibit certain interventions, or it will lead to a more in-depth discussion of advance directives decision-making.

2. Have a working knowledge of a spiritual history tool that fits comfortably into your practice to elicit more information if there is a spiritual issue that is impacting care. All of the tools have basic components of a belief system, support, and coping resources. Each practitioner will find a questioning pattern that fits into the rhythm and style of an interview.

3. Know where to find the documentation of additional spiritual/religious information, and have a working knowledge of the spiritual/psychosocial care plan to make sure there are no issues that can impact medical care/decision-making. Does the social work assessment routinely ask about general and/or specific religious affiliations and support? Is the pastoral care/chaplain information easily accessible?

4. Encourage professional education of spiritual/cultural issues within the nursing facility for personal and team growth. Can the facility reach out to community and religious groups for in-services or participate in “awareness weeks/months”?

5. Participate in Ethics Committee discussions and education. Does your facility have a “working” Ethics Committee that has ongoing educational programs, as well as ad hoc committees that can meet with the interdisciplinary team?

6. Have a working knowledge of the referral resources for spiritual/religious or cultural issues for your patients. Are there interested religious-based support networks in your community?

7. Have a working knowledge of community resources to help in providing cultural information about practices/rituals/restrictions that may impact care. Are there cultural networks/programs to offer awareness training and support for residents?

8. Develop a comfort level of basic values/belief systems, and seek out counsel to answer questions that may impact personal systems. Each physician has a set of beliefs/values that may be challenged when dealing with end-of-life care. Who supports the physician in manners of faith and spirituality?

9. Have a working knowledge of regulatory mandates for the incorporation of spiritual/religious/cultural information. The survey process has been increasingly sensitive to the day-to-day well-being of residents. The physician and medical director have the responsibility to know how the team addresses each aspect of resident care.

10. Be willing to participate in quality improvement projects exploring the interface between spiritual/religious needs and medical care. Are there opportunities for residents to attend services and/or to have religious/spiritual counseling? Are the coping and support systems identified and used?

Healing is not always curing; however, both require hope and solace. The physician has a powerful role in responding to patient needs and being a guiding force. The interdisciplinary team in LTC often can make the process of recognition and assessment of spiritual, religious, and cultural needs easier, particularly if there is physician guidance.

Acknowledgments

The authors of the series “Palliative and End-of-Life Care” are members of the American Medical Directors Association’s Palliative Care Workgroup.

The author reports no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Bright-Long is Medical Director, Maria Regina Residence, Brentwood, NY, and Clinical Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, SUNY Stony Brook.

References

1. Handzo G, Koenig HG. Spiritual care: Whose job is it anyway? South Med J 2004;97:1242-1244.

2. Koenig HG, McCullough M, Larson DB. Handbook of Religion and Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

3. Fuller RC. Spiritual but Not Religious. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005.

4. Vachon M, Fillion L, Achille M. A conceptual analysis of spirituality at the end of life. J Palliat Med 2009;12:53-59.

5. Jerrard J. To comfort always. Caring for the Ages 2004;5:34-43.

6. Erikson EH, Erikson JM, Kivnick HQ. Vital Involvement in Old Age. New York: W.W. Norton & Company; 1986.

7. Maugans TA, Wadland WC. Religion and family medicine: A survey of physicians and patients. J Fam Prac 1991;32:210-213.

8. Oyama O. Koenig HG. Religious beliefs and practices in family medicine Arch Fam Med 1998:7:431-435.

9. Koenig HG, George LK, Titus P. Religion, spirituality, and health in medically ill hospitalized patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:554-562.

10. Koenig HG, Weiner DK, Peterson BL, et al. Religious coping in the nursing home: A biopsychosocial model. Int J Psychiatry Med 1998;27:365-376.

11. Sulmasy DP. Spiritual issues in the care of dying patients “…it’s okay between me and God.” JAMA 2006;11:1385-1392.

12. Koenig HG, George LK, Peterson BL. Religiosity and remission of depression in medically ill older patients. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:536-542.

13. Van Ness PH, Larson DB. Religion, senescence, and mental health: The end of life is not the end of hope. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;10:386-397.

14. Nelson CJ, Rosenfeld BJ, Breitbart W, Galietta M. Spirituality, religion, and depression in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics 2002;43:213-220.

15. Scandrett KG, Mitchell SL. Religiousness, religious coping, and psychological well-being in nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2009;10:581-586. Published Online: September 3, 2009.

16. Koenig HG. Spirituality in Patient Care: Why How, When, and What. 2nd ed. Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press; 2007.

17. Lo B, Ruston D, Kates LW, et al; The Working Group on Religious and Spiritual Issues at the End of Life. Discussing religious and spiritual issues at the end of life: A practical guide for physicians. JAMA 2002;287:749-754.

18. Puchalski CM, Romer AL. Taking a spiritual history allows clinicians to understand patients more fully. J Palliat Care 2000;3:129-137.

19. The Joint Commission standards. www.jointcommission.org/standards/ Accessed June 7, 2010.

20. Kluger J. The biology of belief. Time 2009;173(7):62-64, 66, 70 passim.

21. Park A. Faith and healing: A forum. Time 2009;173(7):74-76, 79.

22. Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med 2009;12:885-904.

23. Romer AL, Puchalski C. Taking a spiritual history allows clinicians to understand patients more fully: An interview with Dr. Christina Puchalski. Innovations in End-of-Life 1999:1(6). www.edc.org/lastacts. Accessed June 7, 2010.

24. Maugans TA. The SPIRITual history. Arch Fam Med 1996;5:11-16.

25. Anandarajah G, Hight E. Spirituality and medical practice: Using the HOPE questions as a practical tool for spiritual assessment. Am Fam Physician 2001;63:81-89.

26. Winn PA, Dentino AN. Quality palliative care in long-term care settings J Am Med Dir Assoc 2004;5:197-206.

27. Nelson-Becker H, Nakashima M, Canda ER. Spirituality in professional helping interventions with older adults. In: Berkman B, Ambruoso S, eds. Oxford Handbook of Social Work in Health and Aging. New York: Oxford University Press;2006:797-807.