Osteonecrosis of the Mandible in a Nursing Home Resident Receiving Bisphosphonate Therapy

Case Presentation

Brief History

Mrs. O is a 71-year-old female resident of a long-term care (LTC) facility who presented in January 2007 with the chief complaint of “swelling below her chin.” The patient had been complaining of pain in her gums for several weeks. She had only two teeth remaining in her lower mandible. Given her risk factors for osteonecrosis of the jaw, she had been referred for dental evaluation a few weeks previously. A full examination and an orthopantography revealed no bone abnormalities. Her dentures were found to be ill-fitting, and recommendations for regular oral hygiene and denture refitting were made.

Mrs. O’s physician visited her emergently at the facility after a report from nursing that she had considerable swelling and redness under her chin. She was transferred to the hospital for further evaluation and treatment.

Her past medical history was significant for a nonambulatory woman with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), anemia, mild pulmonary hypertension, obesity, venous insufficiency with lower-extremity stasis dermatitis, congestive heart failure, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, gastroesophogeal reflux disease, pancreatitis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, multiple myeloma, and osteoporosis.

Her past medical history was significant for a nonambulatory woman with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), anemia, mild pulmonary hypertension, obesity, venous insufficiency with lower-extremity stasis dermatitis, congestive heart failure, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, gastroesophogeal reflux disease, pancreatitis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, multiple myeloma, and osteoporosis.

The multiple myeloma was classified as Stage III. She was diagnosed in March 2005 and had begun treatment on March 12 with the following regimen: dexamethasone 40 mg intravenously (IV), given from the 1st to the 4th and from the 9th to the 12th days of each month, thalidomide 100 mg daily, and zoledronic acid 4 mg IV monthly. The multiple myeloma was under good control with this regimen (no bone pain, no renal insufficiency, and normal calcium) until January 2007, when this pain and swelling occurred.

Mrs. O’s other medications were as follows: darbepoetin alfa 300 mg intramuscularly (IM) weekly, furosemide 40 mg daily, valsartan 180 mg daily, atorvastatin 40 mg daily, sertraline 25 mg daily, sotalol 40 mg daily, fluticasone propionate/salmeterol xinafoate inhaler 250/50 twice daily, calcium carbonate with vitamin D 500 mg/400 IU twice daily, iron sulfate 325 mg 3 times daily, and warfarin 6 mg daily.

The review of systems was negative apart from the chief complaint; in particular, Mrs. O had no fever, hoarseness, dysphagia, or odynophagia. The social history was significant for remote tobacco use and very occasional social alcohol. Mrs. O was a retired teacher’s aide and had lived in the nursing facility for years.

Physical exam at the time of hospital admission was significant for slight distress due to pain. Her temperature was 99.0 degrees F; pulse was 55 beats per minute, and respirations were 18 per minute. Blood pressure was 106/85 mm Hg. Mrs. O’s cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and neurological exams were unremarkable. She had a purple swelling under her chin, approximately 16 cm across and localized more to her right side (Figure 1). Her submandibular/submental region was indurated, erythematous, and tender to palpation but without fluctuance or crepitus. There was swelling at the base of the tongue. She had two teeth in her left anterior lower jaw with some decay. A minute portion of the mandible was visible inside the mouth on the right anterior and left posterior lower mandible (Figure 2).

Physical exam at the time of hospital admission was significant for slight distress due to pain. Her temperature was 99.0 degrees F; pulse was 55 beats per minute, and respirations were 18 per minute. Blood pressure was 106/85 mm Hg. Mrs. O’s cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and neurological exams were unremarkable. She had a purple swelling under her chin, approximately 16 cm across and localized more to her right side (Figure 1). Her submandibular/submental region was indurated, erythematous, and tender to palpation but without fluctuance or crepitus. There was swelling at the base of the tongue. She had two teeth in her left anterior lower jaw with some decay. A minute portion of the mandible was visible inside the mouth on the right anterior and left posterior lower mandible (Figure 2).

Data

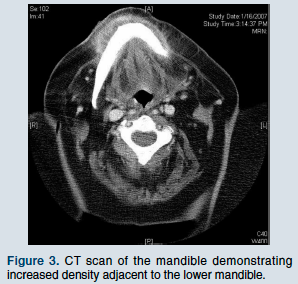

The complete blood count demonstrated a hemoglobin of 9.4 g/dL and a hematocrit of 30.1%. The corpuscular indices were within normal limits; the white blood cell count was within normal limits at 10,000 with 81% neutrophils, 10% monocytes, 0% basophils, and 7% lymphocytes. The platelet count was 232 x 103/µL. Glucose was 103 mg/dL, BUN 18 mg/dL, creatinine 1.0 mg/dL, sodium 138 mEq/L, potassium 4.7 mEq/L, chloride 106 mEq/L, bicarbonate 23 mEq/L, AST and ALT 16 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 50 U/L, calcium 8.8 mg/dL, albumin 3.4 g/dL, and total protein 5.7 g/dL. The computed tomography (CT) scan of her mandible (Figure 3) was read as: “Submandibular soft tissue swelling at the level of the mandibular symphysis, more on the right than the left. The possibility of small submandibular abscesses cannot be excluded. No etiology is identified.”

The complete blood count demonstrated a hemoglobin of 9.4 g/dL and a hematocrit of 30.1%. The corpuscular indices were within normal limits; the white blood cell count was within normal limits at 10,000 with 81% neutrophils, 10% monocytes, 0% basophils, and 7% lymphocytes. The platelet count was 232 x 103/µL. Glucose was 103 mg/dL, BUN 18 mg/dL, creatinine 1.0 mg/dL, sodium 138 mEq/L, potassium 4.7 mEq/L, chloride 106 mEq/L, bicarbonate 23 mEq/L, AST and ALT 16 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 50 U/L, calcium 8.8 mg/dL, albumin 3.4 g/dL, and total protein 5.7 g/dL. The computed tomography (CT) scan of her mandible (Figure 3) was read as: “Submandibular soft tissue swelling at the level of the mandibular symphysis, more on the right than the left. The possibility of small submandibular abscesses cannot be excluded. No etiology is identified.”

Hospital Course

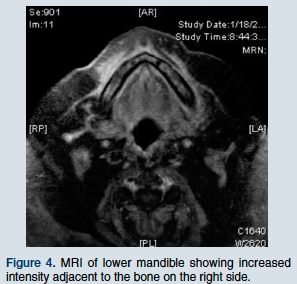

Mrs. O was admitted and started on ampicillin/sulbactam IV (3 g every 6 hr) and vancomycin 1 g IV. Multiple specialists were consulted: Hematology/Oncology; Infectious Disease; Ear, Nose, and Throat; and Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. All concurred with a diagnosis of a submandibular abscess secondary to osteonecrosis of the lower mandible. A second CT scan of her neck failed to reveal bone abnormalities. However, a later magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated abnormal signal in the lower mandible with adjacent cellulites (Figure 4). Vancomycin was discontinued after consultation with Infectious Disease.

Mrs. O was admitted and started on ampicillin/sulbactam IV (3 g every 6 hr) and vancomycin 1 g IV. Multiple specialists were consulted: Hematology/Oncology; Infectious Disease; Ear, Nose, and Throat; and Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. All concurred with a diagnosis of a submandibular abscess secondary to osteonecrosis of the lower mandible. A second CT scan of her neck failed to reveal bone abnormalities. However, a later magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated abnormal signal in the lower mandible with adjacent cellulites (Figure 4). Vancomycin was discontinued after consultation with Infectious Disease.

Mrs. O had a protracted hospital course complicated by bradycardia and sick sinus syndrome that required admission to the Intensive Care Unit, a temporary pacemaker, and, finally, permanent pacemaker insertion. The timing of her procedures was difficult because of her submandibular infection and the need for an MRI prior to pacemaker insertion. Several days after admission, her edematous and painful submandibular abscess spontaneously began to drain through her skin. Blood cultures, cultures of the purulent drainage, and a bone culture from biopsy of the visible exposed bone demonstrated no growth.

A conservative treatment plan was developed, which included continuing ampicillin/sulbactam IV and oral chlorhexidine mouth rinses; surgical intervention was not considered. Mrs. O was discharged to her nursing facility and completed 6 weeks of IV antibiotics without further complication. Her abscess completely resolved, and the areas of exposed bone in her lower mandible looked slightly smaller months later. All forms of corticosteroids were discontinued, including her fluticasone propionate/salmeterol xinafoate inhaler for COPD. She remains a resident in the nursing facility and is currently stable.

Discussion

Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) is a recently recognized complication of bisphosphonate use, first reported by Marx1 in 1995. A systematic review by Woo et al2 summarizes 368 reported cases of bisphosphonate-associated ONJ. Cases presented as exposure of bony parts of the mandible (65%), maxilla (26%), or both (9%). There was a 3:2 female preponderance, and nearly one-third of cases were painless. Sixty percent occurred after some form of dental surgery, predominantly tooth extraction.

Factors predisposing to the development of ONJ are related to the total dose and mode of administration of bisphosphonate, with 94% of cases occurring in patients who received zoledronic acid IV, pamidronate, or both. Patients taking zoledronic acid appear to be at higher risk than those taking pamidronate.3 The cumulative risk of ONJ with zoledronic acid was 1% in the first year and 21% at 3 years of treatment.2

The risk of developing ONJ while taking oral bisphosphonates is unclear, but there have been case reports of its development with alendronate. By March 2006, there had been 170 cases worldwide reported to the manufacturer, and it is estimated that there have been at least 20 million patient-years of experience on alendronate prescribed for osteoporosis or Paget’s disease.4 Increased risk is associated with certain conditions or procedures, specifically tooth extraction, periodontal surgery or therapy, and trauma to the jaws.5

Bisphosphonate dosing is linked to the indication for the medication. Clinical practice guidelines for patients with multiple myeloma recommend monthly bisphosphonate IV for at least 2 years, and then maintenance infusions every 3 months.6 Generally, patients with osteoporosis receive oral bisphosphonates; however, one study examining zoledronic acid for low bone density used IV infusion every 3 months.7 Although oral lesions of ONJ may develop after just a few months of therapy, the median duration of drug use for this complication ranges from 22 to 39 months, with a mean between 9 and 14 months.2

Osteonecrosis of the jaw presents as intraoral lesions that appear as areas of exposed bone with smooth or ragged borders. Sinus tracts, extra- or intraoral, may be present, and some patients present with loose teeth. Painful ulcers may develop in soft tissues adjacent to the bony margins. In early cases, plain radiographs may be negative; however, in more advanced cases, poorly defined areas of osteolysis are seen. One study found that 73.1% of cases had positive radiographic findings at presentation.1 The case discussed in this article is unusual in that the patient developed a submandibular abscess.

Treatment should be directed towards pain control and management of infection. Wide surgical debridement is fairly ineffective, as it is seldom possible to obtain a surgical margin with viable bleeding bone.8 If conservative measures fail, careful local debridement of dead bone with minimal trauma to surrounding tissue should be undertaken. Antibiotics seldom resolve ONJ, and little success has been seen with hyperbaric oxygen treatment.9

Discontinuation of bisphosphonate therapy is recommended for severe cases of ONJ.2 However, the half-life of bisphosphonates is long, and, therefore, there may be no meaningful recovery of osteoclast function and bone turnover for many months after cessation. There are no published trials that document the benefit of discontinuation. Evidence is limited to anecdotal reports of healing and complete resolution of existing sites of ONJ after several months following discontinuation of bisphosphonate therapy. Optimal timing and duration of drug holiday must be weighed against the risks of not taking the medication.2

Osteoporosis is very common, with a prevalence of approximately 75% in community-dwelling elderly women older than age 80 years.10 In nursing home residents, the prevalence is higher: 63.5% for women age 65-74 years and 85.8% for those over age 85 years.11 Osteoporosis combined with a high fall rate and impaired mobility means that the LTC population is particularly vulnerable to fractures. Bisphosphonates have clearly been shown to increase bone mineral density in residents in LTC facilities12 and are now used with increasing frequency.

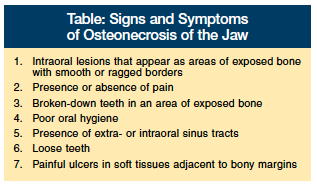

Medical and nursing home staff must be aware of the occurrence of ONJ and have a high level of suspicion for this disorder, especially when providing mouth care for at-risk individuals. The staff should be aware that the risk for ONJ even continues in patients in whom the drug has been discontinued because of the long half-life of bisphosphonates and persistence of drug effect on the bones.13 Continuing education for all staff, including certified nursing assistants who provide daily mouth care, should be instituted, as good oral hygiene is thought to lower risk of development of ONJ14 (Table). Because some lesions may be painless, examination of the oral cavity at regular intervals should be performed, ideally by a dentist, but it can also be performed by a physician or trained registered nurse.

Medical and nursing home staff must be aware of the occurrence of ONJ and have a high level of suspicion for this disorder, especially when providing mouth care for at-risk individuals. The staff should be aware that the risk for ONJ even continues in patients in whom the drug has been discontinued because of the long half-life of bisphosphonates and persistence of drug effect on the bones.13 Continuing education for all staff, including certified nursing assistants who provide daily mouth care, should be instituted, as good oral hygiene is thought to lower risk of development of ONJ14 (Table). Because some lesions may be painless, examination of the oral cavity at regular intervals should be performed, ideally by a dentist, but it can also be performed by a physician or trained registered nurse.

Patients initiating treatment with bisphosphonates should have a comprehensive oral examination. Dental procedures such as tooth extraction, root canal therapy, or periodontal surgery should be completed prior to starting therapy,1 particularly if IV therapy is planned. Invasive dental procedures, especially tooth extraction, should be avoided in patients receiving IV bisphosphonates.15 It is important to remember that these drugs may be administered at a cancer treatment center, and so may be unknown to the nursing facility. As with any medication, a careful assessment of risks and benefits of treatment should be done for all elderly patients taking long-term bisphosphonates. Interestingly, as we learned with this case, “gum pain” in a patient with the appropriate risk factors should raise a concern for this serious complication.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

1. Marx RE, Sawatari Y, Fortin M, Broumand V. Bisphosphonate-induced exposed bone (osteonecrosis/osteopetrosis) of the jaws: Risk factors, recognition, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005;63:1567-1575.

2. Woo SB, Hellstein JW, Kalmar JR. Narrative [corrected] review: Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws [published correction appears in Ann Intern Med 2006;145:235]. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:753-761.

3. Durie BG, Katz M, Crowley J. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and bisphosphonates. N Engl J Med 2005;353:99-102.

4. Bolland MJ, Grey A, Reid IR. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and bisphosphonates: Editorial was confusing. BMJ 2006;333:1122-1123.

5. Ruggiero S. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2008;29(2):96-98, 100-102, 104-105.

6. Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, et al. Mayo Clinic Consensus Statement for the use of bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc 2006;81(8):1047-1053.

7. Reid IR, Brown JP, Burckhardt P, et al. Intravenous zoledronic acid in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. N Engl J Med 2002;346(9):653-661.

8. Ruggiero SL, Mehrotra B, Rosenberg TJ, Engroff SL. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates: A review of 63 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004;62:527-534.

9. Ruggiero S, Gralow J, Marx R, Hoff A, et al. Practical guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with cancer. J Oncol Prac 2006;2(1):7-14.

10. Looker AC, Johnston CC Jr, Wahner HW, et al. Prevalence of low femoral bone density in older U.S. women from NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res 1995;10:796- 802.

11. Zimmerman SI, Girman CJ, Buie VC, et al. The prevalence of osteoporosis in nursing home residents. Osteoporosis Int 1999;9(2):151-157.

12. Greenspan SL, Schneider DL, McClung MR et al. Alendronate improves bone mineral density in elderly women with osteoporosis residing in long term care facilities. A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2002;136:742-746.

13. Edwards BJ, Migliorati CA. Osteoporosis and its implications for dental patients. J Am Dent Assoc 2008;139(5):545-552.

14. American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Dental management of patients receiving oral bisphosphonate therapy: Expert panel recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc 2006;137;1144-1150.

15. Osteonecrosis of the jaw. American Dental Association Website. www.ada.org/prof/resources/topics/osteonecrosis.asp. Accessed August 8, 2008.