Medication Reconciliation and Seamless Care in the Long-Term Care Setting

The evidence in support of medication reconciliation has increased rapidly in recent years, while the need for an improved medication-use system in the LTC setting remains. This article describes the essential elements of medication reconciliation and its application to the LTC setting. First, a case presentation depicts some of the typical clinical problems involving medications that face residents and clinicians in this setting and during transitions of care. Second, a brief literature review of medication reconciliation follows, with a special emphasis on the LTC setting. Third, a practical real-life example of adopting this service in several facilities in one state, the Nursing Home Medication Safety Project in Massachusetts, is reviewed. Finally, suggested strategies for implementation are presented, including implications for clinicians. (Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2009;17[11]:36-40)

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Clinical Scenario

Mr. H is an 88-year-old white man who lives by himself in the house he shared with his wife of over 50 years, until her death two years ago. He is generally alert and oriented and can make his immediate needs known. He is fiercely independent. Despite being forgetful and occasionally confused, Mr. H refuses to accept much help from his two sons and daughter, who live nearby. He is not fond of seeing doctors and often misses appointments. He reluctantly takes medications and may skip them for several days in a row because he feels he is taking too many pills. Mr. H’s medical problems include congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, degenerative joint disease, falls, dizziness, insomnia, and depression. His prescribed medications include: regularly-scheduled digoxin, warfarin, metoprolol, albuterol metered-dose inhaler, and fluoxetine, as well as trazodone as needed for sleep.

One day, Mr. H’s daughter comes to pick him up for an appointment but he does not answer the door. She finds him lying on the floor moaning. She calls 911, and he is taken to the emergency room, where he is diagnosed with a right hip fracture and mild dehydration. He is admitted and undergoes an open-reduction internal fixation procedure that night. His post-operative course is mostly uneventful, but he becomes confused on post-op day 2; he is administered haloperidol intravenously with good results. He also develops a low-grade temperature. The next day, he is discharged from the hospital and admitted to a skilled nursing facility (SNF) for rehabilitation. His discharge medications include: (1) haloperidol as needed for delirium; (2) a higher dose of digoxin, since on hospital admission, his digoxin level was < 0.1; and (3) meclizine as needed for dizziness because Mr. H’s daughter told the hospital staff about her father having been lightheaded at home prior to his admission.

Mr. H arrives on the subacute unit at the nursing home at 5:00 PM on Friday evening; he is the fourth admission that afternoon. He had been in the hospital for 3 days and is now more confused. He is taking 10 medications, including a proton pump inhibitor, ibuprofen, meclizine, senna, docusate, and haloperidol. Mr. H has an unsteady gait and complains of dizziness upon standing.

Mr. H’s confusion increases, and he has a fall related to weakness on his fourth day in the SNF. Laboratory studies reveal a digoxin level of 3.5 (reference range, 0.8-2.4 ng/mL), Hgb/Hct of 8/25 (reference range, 14-18 g/dL/ 39-54%), INR of 5.1 (reference range, 2.0-3.0), and BUN of 70 (reference range, 6-23 mg/dL). He is transferred back to the hospital and diagnosed with an upper gastrointestinal bleed, dehydration, and digoxin toxicity. After 3 days, he is stable and transferred back to the SNF.

Clinical Scenario Questions:

1. What are the potential issues related to failure to reconcile medications between the hospital and SNF in this case?

2. How could potential adverse events in this case have been avoided?

----------

Introduction

Transitions in care can present serious challenges and potential harm to frail, older patients as they move from the hospital to a SNF or from a SNF to home. In particular, comprehensive review of the patient’s medications through the process of medication reconciliation, as will be described, is crucial for determining exactly which drugs patients should be taking when they arrive in their new care setting. As demonstrated in the above clinical scenario, there are typically numerous opportunities for mishaps and adverse events to occur. The following article will provide a brief overview of the evidence for medication reconciliation and describe practical approaches for implementing medication reconciliation in the LTC setting.

Medication Reconciliation and Seamless Care

While the terminology may vary by profession and geographic area, it is generally accepted that seamless care, continuity of care, smooth transitions of care, and coordination of care are important components of a high-performing healthcare system. As Bodenheimer1 argued in an editorial in The New England Journal of Medicine, “recent research strongly suggests that failures in the coordination of care are common and can create serious quality concerns.” Unfortunately, as was observed in the 2007 Commonwealth Fund international survey, a large percentage of the population in seven western industrialized nations, including the United States, reported that they did not have a medical home in which their care was coordinated.2

The need for seamless care is especially important for optimal medication use. It has been proposed that there are eight essential elements of a safe and effective medication-use system,3,4 several of which relate to aspects of seamless care: ongoing monitoring, proper documentation and communication, and active participation of patients in their own care. In Canada, there has been considerable activity in recent years to promote seamless pharmaceutical care.5 A 2005 Australian publication suggests ten principles that should be followed to help achieve seamless pharmaceutical care.6

A subset of seamless pharmaceutical care that has gained prominence in recent years is medication reconciliation. Medication reconciliation, commonly known as “med rec,” involves reviewing the patient’s medication profile to ensure they are on the right medications. This review typically occurs during transitions in care. While the activities involved in medication reconciliation have been in existence for a long time, medication reconciliation as a specific concept is relatively new, first proposed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) within the past decade.7 Since then, it has been widely adopted by professional associations, patient safety campaigns, and accreditation bodies. This adoption has expanded well beyond the United States, as the World Health Organization has included medication reconciliation as one of the core strategies in its multi-nation collaborative initiative, “Action on Patient Safety: High 5s.”8

When medication reconciliation was first proposed by IHI as a strategy to improve the safety of the medication use system, empirical evidence supporting its utility was scarce. However, as has been previously discussed, there is a wealth of empirical evidence showing that patients may experience problems during transitions in care, and medication reconciliation appears well-suited to address these problems. Since it was first proposed, fortunately, the evidence in favor of medication reconciliation has caught up with the perceived benefits.9-11

One setting where there would appear to be a special need for medication reconciliation is in LTC, given the published evidence of problems with medication use. Bootman et al12 estimated the total annual cost of drug-related morbidity and mortality in nursing homes (NHs) in the United States to be $7.6 billion, and they conclude that for every dollar spent on drugs in NHs, $1.33 in healthcare resources is consumed in the treatment of drug-related problems. Another study by Gurwitz and colleagues13 estimated that 350,000 adverse drug events occur each year in NHs in the United States, with over half of these being preventable. In a study of patient transfers from LTC facilities to hospitals, a mean of 3.1 medications were changed upon hospital admission, while a mean of 1.4 medications were changed on readmission to the LTC facilities.14 Adverse drug events that were attributable to medication changes occurred in 20% of transfers.14

Adoption of medication reconciliation in the LTC setting has been limited to date, although it is expanding. Canada’s national patient safety campaign, Safer Healthcare Now!, adopted medication reconciliation in LTC as one of its new patient safety strategies in 2008. Some evidence has emerged to support the value of medication reconciliation in this setting. Boockvar and colleagues15 observed the impact of pharmacist medication reconciliation and communication in a consecutive sample of 168 residents of a LTC facility who were hospitalized and then returned to the LTC facility over a two-year period. The authors conclude that “pharmacist-conducted medication reconciliation in combination with physician communication can improve medication safety and patient outcomes at the time of transfer between facilities.” In another study of multiple hospitals and LTC facilities, a pharmacist transition coordinator did improve inappropriate medication use but had a mixed impact on clinical outcomes and healthcare resource utilization.16

Answers to Clinical Scenario Questions:

1. SNF did not realize which medications were added and which were home medications; SNF was not aware of any home management issues with warfarin/INRs; SNF was not aware of adherence issues at home. Failure to reconcile ibuprofen (patient never took this at home) may have led to interaction with warfarin; failure of hospital and SNF to communicate on most recent INR trends may have led SNF provider to prescribe higher dose of warfarin than was indicated; failure to appreciate that patient routinely skipped his medications at home led to a higher dose of digoxin and digoxin toxicity; use of meclizine to treat dizziness without a thorough work-up may have actually worsened the dizziness (anticholinergic) and caused other symptoms (increased confusion); patient was taking fluoxetine at home, which might have been causing or contributing to dizziness; however, unclear whether patient was even taking this medication.

2. Institute SNF policy for nurses to ask new patients/families about home medications (do not rely on hospital medication reconciliation alone for all relevant information). Consider provider-to-provider communication around complex cases, rather than simply relying on a transfer form or medication list.

The Nursing Home Medication Safety Project

Funded through the Betsy Lehman Center and the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Nursing Home Medication Safety Project began by convening an advisory/consensus panel to review the literature, error data, and national models on medication safety in LTC. The results led to the development of best practices and supporting materials, which were then piloted in 22 Massachusetts NHs. Through a series of collaborative teleconferences with the consensus group and pilot facilities, the materials were evaluated and revised. These and other materials became the basis for the Safe Medication Practices Workbook.17

Funded through the Betsy Lehman Center and the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Nursing Home Medication Safety Project began by convening an advisory/consensus panel to review the literature, error data, and national models on medication safety in LTC. The results led to the development of best practices and supporting materials, which were then piloted in 22 Massachusetts NHs. Through a series of collaborative teleconferences with the consensus group and pilot facilities, the materials were evaluated and revised. These and other materials became the basis for the Safe Medication Practices Workbook.17

Safe Medication Practices Workbook was one of the first resources on medication safety devoted entirely to the LTC practice setting. The workbook presents an overall system for medication management, including the importance of organizational commitment, staff education, process steps, quality improvement and error tracking, resident and family education and involvement, regulations, and resources. Special focus areas include warfarin management, medication reconciliation, and transcription of monthly orders, also known as monthly edits. Practical tips and tools and case studies guide the reader.

Different facilities chose different special-focus areas (reconciliation, warfarin, transcription). After the 22 NH pilot was completed, a one-day kick-off event was held. Speakers were local experts from NHs that had already begun to make some changes with regard to medication safety. Facilities shared their implementation experiences and exchanged stories. Presentations and posters from the NHs revealed new insights and helped other facilities considering implementation of new practices. In addition, the feedback from this conference provided additional ways to improve the workbook, which were incorporated into later revisions.

The Massachusetts experience demonstrated the strengths of the collaborative model. Strong leadership support was present in all of the 22 pilot NHs. They were able to develop interdisciplinary teams which, in many cases, continued after the project. Providing feedback to the team during the project aided in revisions of the workbook, as well as innovative processes within the facilities. The NHs verified the importance of starting small and embedding the new medication safety processes into existing workflow.

In a related study, researchers examined the prevalence of type of medications involved in and sources of medication discrepancies upon admission to the SNF setting in two NHs in Massachusetts.18 A better understanding of medication reconciliation issues in the SNF setting is enabling improved design and implementation of tools and processes to reduce medication errors and adverse events related to failure to reconcile medications in the transfer of patients from the acute care to the SNF setting.

In 2008, the Massachusetts Senior Care Association sponsored two educational programs for SNFs, providing some basic training in quality improvement techniques and an overview of the tools and strategies in the Safe Medication Practices Workbook, with a focus on medication reconciliation and warfarin management. A major health insurer provided some financial support to facilities in their network to participate in the conference and address these priorities.

Discussion and Conclusion

Clinicians performing medication reconciliation often encounter significant challenges as patients transfer to and from the NH setting: a frail elderly population with multiple comorbidities, often including significant functional and cognitive deficits; a fragmented medical system with inconsistently developed lines of communication and incomplete transmission of pertinent patient information; and insufficient alignment of regulatory and economic incentives to promote seamless transitions for patients.

These challenges are readily apparent in the case scenario described in the beginning of this article. Mr. H is a medically complex elderly patient who does not always adhere to the medical regimen he has been prescribed. He is reluctant to take medications and unwilling to accept any assistance from his family. His fragile medical condition is further exacerbated by lack of careful review of his medications on his initial hospital discharge and subsequent NH admission; an unjustified increase in the dose of digoxin (leading to a toxic level); failure to identify a drug-drug interaction between warfarin and ibuprofen (predisposing him to gastrointestinal bleeding); and inappropriate prescription of meclizine, placing him at risk for delirium and falls.

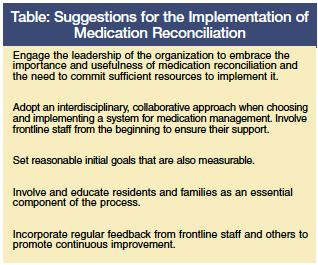

Establishing a reliable, consistent process of medication reconciliation in the LTC setting is both achievable and effective. Numerous organizations, including the IHI, Joint Commission, Institute of Medicine, and World Health Organization have raised the priority and fostered a culture in favor of medication reconciliation. Mounting evidence from clinical trials points to the utility of medication reconciliation in reducing medication discrepancies, adverse drug events, and mortality. The promising results of the Massachusetts Nursing Home Medication Safety Project point to a number of useful strategies for implementing careful and consistent medication review during transitions in care.

Although encouraging progress has occurred to date, there are further improvements to be made in improving communication, refining electronic records to facilitate accuracy and the timely transmission of information, and educating patients, clinicians, and health system administrators about the benefits of, and optimal methods for, performing medication reconciliation. A recent summary of 15 care coordination programs published in The Journal of the American Medical Association revealed that in-person contact and collaboration with the patient’s physician around medication issues are critical.19,20 Medication reconciliation does not lend itself to a one-size-fits-all solution, but there are nonetheless practical approaches that can be implemented with an expectation for success.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the individuals at Masspro and the Betsy Lehman Center for Patient Safety and Medical Error Reduction who supported and collaborated on the development of the Safe Medication Practices Workbook, and to the Massachusetts nursing homes that pilot- tested the tools and processes for the workbook.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. MacKinnon is Associate Director for Research and Professor, College of Pharmacy, Associate Professor, School of Health Administration and Department of Community Health & Epidemiology, Faculty of Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada; Dr. Kaiser is Associate Professor, Geriatrics and Palliative Care, George Washington University School of Medicine, and Attending Physician, Geriatrics and Extended Care, Washington, DC Veterans Affairs Medical Center; Ms. Griswold is Executive Director of the Massachusetts Coalition for the Prevention of Medical Errors, Burlington, MA; and Dr. Bonner is Executive Director of the Massachusetts Senior Care Foundation, and Assistant Professor, University of Massachusetts Graduate School of Nursing, Worcester, MA.

Resources for Information on Medication Reconciliation

Internet

Masspro. A Systems Approach to Quality Improvement in Long-Term Care: Safe Medication Practices Workbook. https://www.masspro.org/NH/docs/tools/SafeMedPrac06_8-07Upd.pdf

Institute for Health Care Improvement. Medication Reconciliation Review. https://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/PatientSafety/MedicationSystems/Tools/Medication+Reconciliation+Review.htm

Institute for Health Care Improvement. Medication System Tools. https://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/PatientSafety/MedicationSystems/Tools/#Medication%20Reconciliation

The Joint Commission,“Using Medication Reconciliation to Prevent Errors.” Sentinel Event Alert, Issue 35, January 25, 2006. https://www.jointcommission.org/sentinelevents/sentineleventalert/sea_35.htm

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada and the Canadian Patient Safety Institute. Safer Healthcare Now! Getting Started Kit: Medication Reconciliation on Long-Term Care. https://www.saferhealthcarenow.ca

Articles

Agrawal A, Wu WY. Reducing medication errors and improving systems reliability using an electronic medication reconciliation system. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2009;35(2):106-114.

Nigam R, MacKinnon NJ, Hartnell NR, et al. Development of Canadian safety indicators for medication use. Healthc Q 2008;11:47-53.

Textbooks

Safe and Effective. The Eight Essential Elements of an Optimal Medication-Use System. MacKinnon NJ, ed. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2007.

Seamless Care: A Pharmacist’s Guide to Providing Continuous Care Programs. MacKinnon NJ, ed. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2003.

References

1. Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care--A perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med 2008;358(10):1064-1071.

2. Schoen C, Osborn R, Doty MM, et al. Toward higher-performance health systems: Adults’ health care experiences in seven countries, 2007. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2007;26(6):w717-w734.

3. Grainger-Rousseau TJ, Miralles MA, Hepler CD, et al. Therapeutic outcomes monitoring: Application of pharmaceutical care guidelines to community pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 1997;NS37:647-661.

4. MacKinnon NJ. Risk assessment of preventable drug-related morbidity in older persons [dissertation]. Gainesville: University of Florida; 1999.

5. MacKinnon NJ, Zwicker LA. Review of Seamless Care--Backgrounder. In: Seamless Care: A Pharmacist’s Guide to Providing Continuous Care Programs. MacKinnon NJ, ed. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2003:1-12.

6. Australian Pharmaceutical Advisory Council. Guiding Principles to Achieve Continuity in Medication Management. Canberra, Australia: Publications Production Unit, Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services; 2005.

7. Fernandes OA, MacKinnon NJ. Is the prioritization of medication reconciliation as a critical activity the best use of pharmacists’ time? The “PRO” Side. Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 2008;61(2):149-150.

8. Action on patient safety—high 5s. Geneva (Switzerland):World Health Organization Website. https://www.who.int/patientsafety/solutions/high5s/en/ Accessed February 26, 2009.

9. Bond CA, Raehl CL. Clinical pharmacy services, pharmacy staffing, and hospital mortality rates. Pharmacotherapy 2007;27(4):481-493.

10. Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ, Schnipper JL. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: A systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2006;166(9):955-964.

11. Nickerson A, MacKinnon NJ, Roberts N, Saulnier L. Drug-therapy problems, inconsistencies and omissions identified during a medication reconciliation and seamless care service. 2005;8 Spec No:65-72.

12. Bootman JL, Harrison DL, Cox E, The health care cost of drug-related morbidity and mortality in nursing facilities. Arch Intern Med 1997;157:2089-2096.

13. Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Avorn J, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events in nursing homes. Am J Med 2000;109:87-94.

14. Boockvar K, Fishman E, Kyriacou CK, et al. Adverse events due to discontinuations in drug use and dose changes in patients transferred between acute and long-term care facilities. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:545-550.

15. Boockvar KS, Carlson LaCorte H, Giambanco V, et al. Medication reconciliation for reducing drug-discrepancy adverse events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2006;4(3):236-243.

16. Crotty M, Rowett D, Spurling L, et al. Does the addition of a pharmacist transition coordinator improve evidence-based medication management and health outcomes in older adults moving from the hospital to a long-term care facility? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2004;2(4):257-264.

17. A Systems Approach to Quality Improvement in Long Term Care: Safe Medication Practices Workbook. Masspro. Accessed February 26, 2009.

18. Tjia J, Bonner A, Briesacher BA, et al. Medication discrepancies upon hospital to skilled nursing facility transitions. J Gen Intern Med. Published Online: March 17, 2009.

19. Peikes D, Chen A, Schore J, Brown R. Effects of care coordination on hospitalization, quality of care, and health care expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries: 15 randomized trials. JAMA 2009;301(6):603-618.

20. Ayanian JZ. The elusive quest for quality and cost savings in the Medicare program. JAMA 2009;301(6):668-670.