Management of Diabetes Mellitus in the Nursing Home

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM), primarily type 2, is a prevalent, resource-intensive condition in nursing homes (NHs), which may have significant impact on residents’ function and quality of life. Upon admission to a NH, 26.4% of residents have a diagnosis of DM, including short-stay (< 6 months) and long-stay residents (> 6 months), whose placement may be permanent.1 Almost half of residents with DM will become long-stay residents.1 Compared to those admitted without DM, residents with DM have a higher burden of comorbid disease, disability, and cognitive impairment, pain, depression, polypharmacy, and require more nursing care.1 Older adults with DM are at higher risk of developing several geriatric syndromes, including injurious falls,2,3 incident disability,4 cognitive impairment,5 urinary incontinence (UI),6 depression,7 and persistent pain,8 if not already present. While the goals of care for short-stay and long-stay residents may differ, avoiding iatrogenic harm is a major focus for both. This is particularly true for frail NH residents with DM who are at high risk for hypoglycemia or other complications of medical therapy such as postural hypotension.

As a result, management of DM in the long-term care setting requires supreme clinical judgment, taking into account the resident’s care preferences, comorbid conditions, and estimated life expectancy. All of this information must be used to make a realistic assessment of the likely benefits and risks of treatment for DM, and associated conditions consistent with the resident’s short- and long-term goals.

In 2003, an expert panel convened by the California Healthcare Foundation/American Geriatrics Society published Guidelines for Improving the Care of the Older Person with Diabetes Mellitus. The major aim of the guideline was to provide clinicians with a framework for prioritizing recommendations for the management of glycemia, and preventing micro- and macrovascular disease in the population of older adults with DM and heterogeneous health status.9 The guideline noted that while intensive risk management is appropriate for robust older adults with good function, it might be inappropriate in frail older adults with limited life expectancy, where the focus of care often shifts to prevention of symptomatic hyperglycemia and reduction of the burden of medical therapy. Furthermore, the guideline noted that geriatric syndromes might complicate the management of DM or constitute a primary focus of care. As a result, it recommended that healthcare providers screen for and manage geriatric syndromes. The guideline provides the basics of a framework to help clinicians prioritize competing comorbidities. Subsequent guidelines by the American Diabetes Association have included explicit reference to these guidelines and have endorsed its message.10 In addition, process-based quality indicators for long-stay NH residents with DM have been developed in an effort to improve outcomes while keeping the unique needs of this population in mind.11

In addition to these considerations (ie, comorbid illness, geriatric syndromes, reduced life expectancy, and shifting priorities of care), physicians and other healthcare providers practicing in the long-term care setting often find that managing residents with DM is complicated by care transitions, dependency that affects food and water intake, and conditions such as dementia and stroke that interfere with patient-provider communication. For many frail individuals, attempting to maximize treatment for all possible diseases and syndromes may lead to harm through side effects, drug-drug and drug-disease interactions, and dissatisfaction with a complex and/or costly regimen.12 As a result, treatment goals for patients with severe dependency, terminal illness, unstable medical conditions, or who are likely to change care environments in the short term typically focus on improvement of daily function and quality of life, and avoidance of hypoglycemia and symptomatic hyperglycemia. Moderate glycemic control, usually achievable within weeks, is consistent with these aims and may reduce fatigue, polyuria, and possibly improve cognitive function.

Therapy intended to reduce macrovascular and microvascular risks is more consistent with long-range care goals (measured in years) and is more appropriate for stable residents with an extended life expectancy. For example, within 10 years of being diagnosed with type 2 DM, 20% of adults will have had a major cardiovascular event, but less than 5% will have developed blindness, and less than 2% will have developed end-stage renal disease (ESRD).13 Data from randomized controlled trials suggest that prevention of macrovascular complications may be realized within 2-3 years of intensive blood pressure and lipid treatment.14,15 Conversely, prevention of intermediary outcomes related to diabetic retinopathy (need for photocoagulation) or nephropathy probably requires at least 8 or more years of intensive glycemic control.14,15 Benefit from intensive glycemic therapy may occur in a shorter timeframe for residents with existing retinopathy or nephropathy, though at the expense of an increased risk of hypoglycemia.

Furthermore, older adults and their caregivers may express a range of personal values and preferences for care that greatly impact healthcare decisions.12 Many long-stay residents may wish to reduce threats to their short-term independence; others may wish to reduce the risk of distal outcomes, such as stroke, while others may wish to reduce their burden of medical care. When interviewed, community-dwelling older adults with DM more commonly cited maintaining independence as a goal than remaining alive or preventing DM complications.16

Therefore, developing an individualized treatment plan for NH residents with DM requires making a holistic assessment of the resident’s health status, informed by an understanding of the resident’s or surrogate decision maker’s care preferences. This process includes: (1) estimating the impact of DM, comorbid disease, and geriatric syndromes on the resident’s short- and long-term health status, comfort, and function; (2) estimating the likely impact that interventions to mitigate or prevent adverse outcomes resulting from DM, comorbid disease, or geriatric syndromes will have for the resident within his or her estimated life expectancy; (3) understanding resident and caregiver goals and preferences; and (4) developing care strategy that prioritizes therapies based on these considerations.

The following examples will illustrate these points.

An 80-year-old female with DM for 15 years is admitted to a NH facility for rehabilitation after open reduction and fixation of a fractured femur. Prior to her hospitalization, she led an active social life and walked 2 miles per day. She followed an intensive medical regimen to manage her glycemia, blood pressure, and lipids. Her short-term goal is to regain maximum physical function; her long-term goals are to prevent macrovascular and microvascular complications. During admission for rehabilitation, her oral intake is somewhat erratic. Her healthcare team chooses a medical regimen that aims for moderate glycemic control (fasting blood glucose 120-140 mg/dL and evening glucose < 180) to avoid complications of hypo- or hyperglycemia. She will resume intensive glycemic management once she has returned home and resumes predictable oral intake and physical activity.

A 70-year-old male NH resident with paraplegia due to spinal cord injury and mild vascular dementia has had DM and hypertension for 15 years. He also has early proliferative diabetic retinopathy. In spite of this, he is able to enjoy reading the sports page daily and watching television. During a meeting with the healthcare team, the resident and his family agree that preventing blindness is critical to his quality of life. His son, speaking on his father’s behalf, affirms that the resident wants to continue an intensive medical regimen to control his glycemia and blood pressure; they accept that tight glycemic control raises his risk for hypoglycemia.

A 65-year-old female with moderately severe dementia and DM is admitted to a NH after hospitalization for myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure. At a team meeting conducted after she has been a resident for a month, it is clear that she will remain in the facility. She dislikes finger-stick glucose monitoring, and her daughter feels that her mother’s most important goals are to be comfortable, enjoy food somewhat liberally, and be allowed to go out with her daughter for weekly car rides. The team chooses the simplest medical regimen possible to achieve moderate glycemic control.

Continue to Next Page for Components of Treatment

COMPONENTS OF TREATMENT

The following is a summary of common therapies for patients with DM, and the special consideration that must be made for those who are NH residents.

Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease

Blood pressure and lipid management in adults with DM reduces cardiovascular morbidity and mortality after approximately 2-3 years. Optimal blood pressure targets are less clear, and some of the benefits of treatment may be independent of the medications’ effects on blood pressure.14 Several studies, which included large numbers of older adults, found benefit with target blood pressures of less than 140/90. However, other studies, which included younger adults, found reduction in cardiovascular endpoints with less tight control.9 Additionally, epidemiologic evidence suggests blood pressure lower than 140/90 may be associated with increased mortality among patients older than age 85.17 All classes of antihypertensive drugs likely have equal efficacy in reducing morbidity and mortality.9,14,18 Treatment of patients with diabetic nephropathy with angiotensin-receptor antagonists for 3-4 years reduces progression of renal disease and incidence of ESRD.19,20

Older adults are at higher risk of developing orthostatic hypotension, which may be worsened by diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Caution should be exercised when prescribing antihypertensive medications for patients at risk for orthostatic hypotension, because its presence increases the patient’s risk for falling. It is also worth noting that orthostatic hypotension may occur in the absence of dizziness, and, therefore, blood pressure should be measured in the supine and standing position when relevant to the patient’s functional status.21

Treatment with 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins), regardless of baseline cholesterol level, after 2-5 years is effective in primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular events and mortality among adults with type 2 DM.22,23 A significant number of adults age 70-80 were included in these trials. However, the utility of statins in the oldest old (age >85) is unclear. Low total cholesterol, especially in this age group, may be a marker of disease burden and associated with greater mortality.24 Thus, the benefit of using a statin in the very old with low baseline total cholesterol is unproven.

Aspirin use is effective for secondary prevention of major cardiovascular events in patients with DM. Evidence for primary prevention efficacy is less robust. The benefits of aspirin use must be weighed against the increased relative risk of hemorrhagic stroke or major gastrointestinal bleeding associated with it.25

Glycemic Control: Activity

While the benefits for managing weight and glycemia, and improving physical conditioning for residents with DM are well recognized, exercise sufficient for achieving these goals may not be feasible--and may even be dangerous--for some NH residents with physical and cognitive impairments due to deconditioning, arthritis, visual problems, autonomic and peripheral neuropathy, balance problems, and dementia. When appropriate, nursing home residents should participate in a group or individual exercise program or physical therapy.

Glycemic Control: Diet

A small crossover design study of nursing home residents did not find that a diabetic diet improved glycemic control.26 Restrictive diets may be associated with protein-calorie malnutrition among nursing home residents.27 As many as 20% of NH residents with DM are underweight,28 and further caloric restriction may be hazardous. Given the risk of hypoglycemia with some forms of therapy, it is important for nursing home residents to receive food they enjoy to ensure consistent food intake. It is our recommendation that restrictive diets be used only in overweight, nonsarcopenic residents who are far from achieving their individualized treatment goals.

Hydration is also very important in this population. Decreased thirst perception, dementia, and difficulty accessing liquids may lead many NH residents to be dehydrated or volume-depleted at baseline. The addition of significant glucosuria will exacerbate this, and may lead to higher rates of hyperglycemic non-ketotic states. When residents are at risk for inadequate fluid intake, diet orders should include explicit instructions for ensuring that an adequate volume of liquid is consumed.

Glycemic Control: Medications

Tight glycemic control is likely appropriate for only a minority of NH residents, since no clinical trial data are available that examine the effects of glycemic control in frail older adults or the oldest old.13,14 In addition, there is not consensus as to the optimal target HbA1c level among frail older adults with complex health status.11,29 For this reason, the goal of glycemic therapy for most NH residents is to reduce symptoms associated with excessive hyperglycemia. To achieve this, a target HbA1c of approximately 8% is adequate. Because microvascular complications of poor glycemic control take approximately 10-15 years to develop, older adults living in NH with new onset of DM are not likely to benefit from tight glycemic control, but will incur increased risk of hypoglycemia. The exception may be those with retinopathy or nephropathy. Tight control of blood glucose with a target HbA1C of less than 7% may be appropriate if this can be implemented safely.

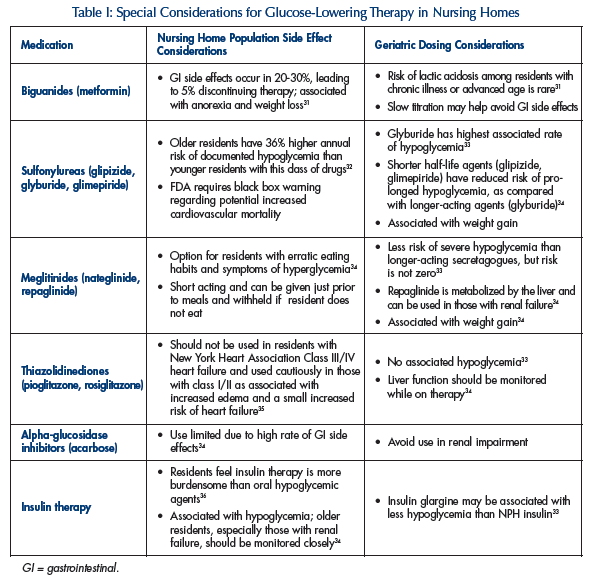

Metformin therapy is the only medication shown to reduce mortality, stroke, and DM-related endpoints significantly, specifically in overweight residents, when compared with insulin or agents.30 Table I31-36 lists specific nursing home considerations for antidiabetic agents.

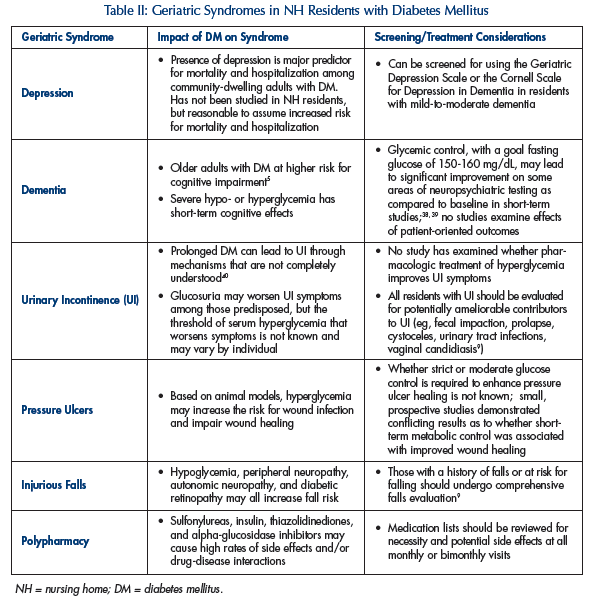

Screening for Geriatric Syndromes

Six geriatric syndromes (ie, polypharmacy, depression, cognitive impairment, urinary incontinence, injurious falls, and pain) are more prevalent in persons with DM, or are felt by experts to be more likely. In addition, DM is associated with a higher risk of pressure ulcer development among residents of high-risk NHs.37 Screening for these syndromes in NH residents with DM should be done as a part of the initial evaluation, and repeated periodically over time.9 Table II38-40 describes the relationship between many of these syndromes and DM.

CONCLUSION

Care of a heterogeneous group of NH residents with DM requires individualization of treatment goals based on health status, life expectancy, and preferences. Frail older adults may experience increased harm when healthcare providers attempt to aggressively manage multiple comorbidities and implement complex treatment regimens. Modification of cardiac risk factors and treatment of geriatric syndromes provide more immediate benefit than intensive hyperglycemic control. Ongoing discussions with the residents, families, and staff will ensure appropriate treatment goals.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Durso is a Miller-Coulson Scholar, Center for Innovative Medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.