Implementing Long-Term Care Infection Control Guidelines Into Practice: A Case-Based Approach

Infections result in significant morbidity and mortality among residents of long-term care facilities (LTCFs). The prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant organisms is increasing along with the medical complexity of residents in this setting. However, given the heterogeneity of LTCFs and diversity of residents, the management and prevention of infections and antimicrobial resistance is often not straightforward. In addition, infection prevention methods must be balanced with other clinical goals and the optimization of residents’ functional status, comfort, and quality of life. This article aims to apply the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) guidelines to real-world scenarios using a case-based approach and present key points for wider dissemination to clinical practitioners. (Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2010;18[2]:28-33)

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction

More and more often, healthcare in the United States is delivered outside of the acute care setting. Today, outpatient clinics, ambulatory surgical centers, rehabilitation units, and long-term care facilities (LTCFs) are sites of care that continue to grow in importance.1,2 Not unexpectedly, infection rates also are increasing at these ancillary sites. Approximately 1.5-2 million infections occur each year in LTCFs, a rate that is similar to acute care hospitals. Infections among LTCF residents are associated with increased mortality and morbidity, and frequently result in transfers to acute care hospitals. Hospitalization of older adults can result in serious adverse consequences including delirium, pressure ulcers, adverse drug events, decline in functional status, and the acquisition of antimicrobial-resistant infections.3

Many infections in LTCFs are caused by multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), and multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli (R-GNB). For every older adult infected with an MDRO, many more are asymptomatically colonized with these organisms.3,4 These asymptomatic carriers are at increased risk of symptomatic infections. Perhaps even more important, carriers serve as reservoirs for MDRO transmission within LTCFs, as well as in acute care hospitals.

The LTCF environment presents unique challenges to implementing an effective infection prevention program. Most notably, LTCF residents are a highly vulnerable population with enhanced susceptibility to infections, in large part due to an increased prevalence of underlying risk factors. These factors include the presence of multiple comorbid conditions, an increased severity of illness, functional and cognitive impairment (predisposing to aspiration and pressure ulcers), incontinence and resultant need for indwelling catheter use, and the institutional environment itself.3 Most infections found among these residents are thought to be endogenous in nature, often resulting from the resident’s own flora. The high level of medical complexity frequently results in polypharmacy and the need for urgent transfers to the acute care hospital. The combination of these factors results in a vulnerable resident highly prone to infections and subsequent transmission of resistant pathogens. Compounding these host factors are suboptimal full-time equivalents for registered nurses, nursing aides, and therapists, along with high staff turnover. Despite these challenges, significant progress has been made in the past two decades to advance research and inform policy in this area.

The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC) recently updated their LTC infection prevention guidelines.1,2 Too often, guidelines are written but not translated to clinical practice. In this article, we aim to apply the SHEA/APIC guidelines to real-world scenarios using a case-based approach in order to highlight key recommendations for practitioners caring for patients in the LTC setting.5

Case 1

You are called to evaluate an 84-year-old woman with mild dementia and neurogenic bladder with a chronic indwelling urinary catheter, now presenting with increasing agitation and abdominal discomfort. Her appetite has reduced substantially, and she has a low-grade temperature of 100.4 degrees F. On physical exam, her blood pressure is 120/54 mm Hg, pulse rate is 85/minute, and respirations are 14/minute.

Key Questions:

• Should I give my patient antimicrobial medication?

• How can I prevent catheter-related urinary tract infections in the future?

The key management questions for such a patient are to decide whether this patient has a symptomatic UTI and whether she should be started on antimicrobial treatment. UTIs remain the most common infection affecting older adults in LTCFs and are a common cause of bacteremia, often leading to hospital transfers. The use of indwelling catheters, poor functional status, and underlying medical conditions in residents of LTCFs contribute to an increased risk for UTIs. UTI rates are now considered nursing facility quality indicators and are reported quarterly by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS; www.medicare.gov/NHCompare/home.asp).

Recent rates of symptomatic UTI range from 0.1 to 2.4 infections/1000 resident days.6 At the same time, presumed UTI is a major cause of inappropriate antimicrobial usage. Asymptomatic bacteriuria occurs in up to 50% of all LTCF residents. Nearly 100% of patients with a chronic (more than 30 days) urinary catheter will grow bacteria in their urine. The case patient will likely be bacteriuric, even if she does not have symptomatic infection. Determining the presence of true infection can be very challenging in patients with baseline cognitive impairment since the presence or absence of “symptoms” may not be clear cut.7,8

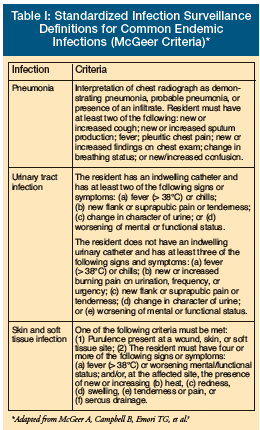

To help accurately determine the presence of a symptomatic UTI, diagnostic criteria have been developed for this population (Table I).9 In noncatheterized patients, at least three of the following signs and symptoms should be present: (1) fever (> 38 degrees C) or chills; (2) new or increased burning pain on urination, frequency, or urgency; (3) new flank or suprapubic pain or tenderness; (4) change in character of urine; and/or (5) worsening of mental or functional status. In the patient with a urinary catheter, at least two of the following signs or symptoms should be present : (1) fever (> 38 degrees C) or chills; (2) new flank or suprapubic pain or tenderness; (3) change in character of urine; and/or (4) worsening of mental or functional status. Since the most common source of infection among patients with an indwelling urinary catheter is the urinary tract, the presence of fever and increased confusion or worsening functional status should be treated as a UTI if other sources of infection can be excluded.10,11

To help accurately determine the presence of a symptomatic UTI, diagnostic criteria have been developed for this population (Table I).9 In noncatheterized patients, at least three of the following signs and symptoms should be present: (1) fever (> 38 degrees C) or chills; (2) new or increased burning pain on urination, frequency, or urgency; (3) new flank or suprapubic pain or tenderness; (4) change in character of urine; and/or (5) worsening of mental or functional status. In the patient with a urinary catheter, at least two of the following signs or symptoms should be present : (1) fever (> 38 degrees C) or chills; (2) new flank or suprapubic pain or tenderness; (3) change in character of urine; and/or (4) worsening of mental or functional status. Since the most common source of infection among patients with an indwelling urinary catheter is the urinary tract, the presence of fever and increased confusion or worsening functional status should be treated as a UTI if other sources of infection can be excluded.10,11

Case 2

An 84-year-old man with congestive heart failure, advanced dementia, and moderate impairment of activities of daily living resides in a LTCF. He presents with confusion, cough, and fever up to 100.6 degrees F. The patient’s son states that his father has been seeing strange people in trees when he takes his father for walks in the afternoon. On physical exam, his blood pressure is 101/40 mm Hg, pulse rate is 125/minute, respirations are 26/minute, and pulse oximetry is 84%.

Key Questions:

• What are the next steps in management of this patient?

• How can pneumonia be prevented in LTCF residents?

Every LTCF should establish a program to prevent UTIs, including the development of criteria for use of long-term indwelling urinary catheters and protocols for limiting or eliminating unnecessary catheter use (Recommendation I.3). An ideal infection control committee structure is shown in Table II. Routine urinalysis or urine culture to screen for bacteriuria or pyuria is not recommended, nor is irrigation of indwelling catheters with saline or antiseptics. The maintenance of a sterile, closed drainage system is essential. For this reason, the use of leg bags is generally discouraged due to the increased risk for interruption of a closed drainage system. The SHEA/APIC guidelines recommend that the LTCFs develop policies and procedures for aseptic connection, cleaning, and storage of leg bags (Recommendation I.3). Simple measures such as maintaining adequate hydration are also important. Finally, appropriate hand hygiene before and after any catheter care should be emphasized.

Every LTCF should establish a program to prevent UTIs, including the development of criteria for use of long-term indwelling urinary catheters and protocols for limiting or eliminating unnecessary catheter use (Recommendation I.3). An ideal infection control committee structure is shown in Table II. Routine urinalysis or urine culture to screen for bacteriuria or pyuria is not recommended, nor is irrigation of indwelling catheters with saline or antiseptics. The maintenance of a sterile, closed drainage system is essential. For this reason, the use of leg bags is generally discouraged due to the increased risk for interruption of a closed drainage system. The SHEA/APIC guidelines recommend that the LTCFs develop policies and procedures for aseptic connection, cleaning, and storage of leg bags (Recommendation I.3). Simple measures such as maintaining adequate hydration are also important. Finally, appropriate hand hygiene before and after any catheter care should be emphasized.

Pneumonia is the second most common cause of infection and the leading cause of infection-related death among LTCF residents, with an incidence ranging from 0.3 to 2.5 episodes per 1000 resident care days.1,2 A number of factors predispose older adults to pneumonia, including decreased clearance of bacteria from the airways, altered oral flora, poor functional status, presence of feeding tubes, swallowing difficulties and chronic aspiration, as well as inadequate oral care.12,13 Such underlying diseases as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart disease further increase the risk of pneumonia in this population.

The clinical presentation of pneumonia in the elderly is frequently not typical. While there tends to be a paucity of the usual respiratory symptoms, recent studies have identified fever, new or increased cough, altered mental status, and increased respiratory rate above 30 bpm as important clinical findings in pneumonia.14 Although obtaining sputum for diagnosis can be logistically difficult, obtaining a chest radiograph is now more feasible than in the past. In general, the work-up for suspected pneumonia should include pulse oximetry, chest radiograph, complete blood count with differential, serum creatinine, and blood urea nitrogen.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common etiologic agent, accounting for about 13% of all cases, followed by Hemophilus influenzae (6.5%), S. aureus (6.5%), Moraxella catarrhalis (4.5%), and aerobic gram-negative bacteria (13%). Legionella pneumonia also is a concern in LTCFs.15

The mortality rate for LTCF–acquired pneumonia is significantly higher than for community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly population. Factors associated with poor prognosis include impaired physical and cognitive functional status. Several prognostic indices have been developed to aid management decisions. These include the nursing home–specific criteria by Naughton et al,14 pneumonia severity index, CURB-65, and modified American Thoracic Society guidelines.15 For example, mortality exceeds 30% among patients who have two of the following: respiratory rate greater than 30/minute, heart rate greater than 125/minute, acute mental status changes and history of dementia. Thus, the case patient with dementia and acute mental status changes has an estimated 30% risk of death. Given the poor prognosis associated with pneumonia among LTCF residents, especially in severe cases, a candid discussion with the family members to clarify goals of care is prudent.

As with other infections, targeted efforts to prevent pneumonia are essential. The SHEA/APIC guidelines emphasize various infection control measures that include hand hygiene by LTCF staff after contact with respiratory secretions, wearing gloves for suctioning, elevating the head of the bed 30-45 degrees during tube feeding and for at least 1 hour after completion of feeding to decrease aspiration, and vaccination of high-risk residents with pneumococcal vaccine (Recommendation I.4).16,17 The evidence for the efficacy of pneumococcal vaccine in high-risk populations, including older adults, is debated. However, the vaccine is safe, relatively inexpensive, and recommended for routine use in individuals over age 65 years (Recommendation J.6).18 Similar to UTI rates, pneumococcal vaccine rates for a facility are publicly reported on the CMS website (www.medicare.gov/NHCompare/home.asp).

Case 3

An 88-year-old man recently returns to his LTC residence following a hospital stay during which he was treated for dehydration. As part of the hospital infection control protocol, he had an anterior nares (nasal) surveillance culture performed, which yielded MRSA. However, he had no signs or symptoms of an actual MRSA infection at the hospital or upon returning to the LTCF. The resident is otherwise healthy, continent of urine and stool, and requires minimal assistance with ADL. Prior to his recent hospital admission, he ate meals outside of his room and regularly attended community activities within the facility.

Key Questions:

• Does this resident require a private room, or should he share a room with another MRSA–positive resident?

• Should this resident be allowed to attend communal meals and activities?

• Should an attempt be made to decolonize the resident?

The current SHEA/APIC guidelines suggest that many of these decisions should be based in part on the resident’s current clinical situation (Recommendation G.7).1,2 In this case, the resident is otherwise healthy and unlikely to transmit MRSA to other residents or the environment. Thus, simply being colonized with MRSA neither necessitates a private room nor rooming with another MRSA–positive resident. In most instances, Standard Precautions should suffice. Furthermore, this resident should not be prohibited from attending communal meals or activities that are important to maintaining his quality of life. Decolonization strategies such as use of mupirocin ointment applied to the nasal epithelium or bathing with chlorhexidine may transiently reduce the likelihood of transmission.19,20 However, prolonged use of these methods could result in increased susceptibility to other infections and, in the case of chlorhexidine, overdrying of the skin. Furthermore, it has been reported that decolonization efforts may have lower utility in LTCFs because residents are either more apt to maintain colonization or become recolonized.21,22 McConeghy et al23 have published a more thorough review of the decolonization literature. Systematic antimicrobial agents (in contrast to the topical therapies listed above) should not be used to try to decolonize an LTCF resident. Overuse of antibiotics is a major problem in LTCFs and actually increases resistance, which ultimately limits therapeutic options when residents actually have infections.

Healthcare worker contacts with this MRSA–colonized resident could increase the probability of transmission to other residents and contamination of environmental surfaces, especially if there is potential for contact with body secretions, wounds, or stool. If this is the case, Standard Precautions for healthcare contacts should include the use of gowns and gloves as necessary (Recommendation G.4). Furthermore, recognizing that the patient’s clinical presentation may change and the potential for transmission may increase, infection control policies regarding this resident should be adjusted based on changes in his clinical condition. For example, if he is no longer continent or otherwise unable to control bodily secretions, including draining wounds, the potential for transmission to other residents and contamination of the environment will increase, and it may be necessary to restrict movement to common areas to reduce this potential.

Case 4

A 78-year-old woman returns to the LTCF after a 1-week hospital stay for a broken hip and an additional 1-week stay in an acute rehabilitation hospital. At the rehabilitation facility, the patient had a urine culture sent for unclear reasons. This culture yielded Acinetobacter baumanni that was resistant to all antimicrobials except for imipenem. She has been placed in a single room at the rehabilitation institute but was not placed on contact precautions. Upon return to the nursing home, she has no urinary catheter in place and has no fever or urinary symptoms. The hospital in which the patient was initially treated for her broken hip routinely places all patients with colonization or infection due to Acinetobacter species on contact precautions for the duration of their hospital stay. The resident is otherwise healthy and is continent of urine and stool. Prior to her fall she was independent with ADL but now requires assistance due to her impaired mobility. However, she enjoys eating and socializing in common areas with other residents.

Key Questions:

• The resident has no urinary symptoms, so is there a role for treatment or repeating of diagnostic tests such as urine culture or urinalysis?

• Should this resident be placed in a private room?

• Should contact precautions be used by staff when making contact with this patient? Should this patient be restricted from participating in group events or from spending time in common areas?

• Is there a role for sending other types of cultures, such as a perirectal or nares swab?

• Is there a role for decolonization or empiric treatment with antimicrobial agents?

As highlighted in Case 1, there is not an indication to treat this patient or conduct further testing for asymptomatic bacteriuria.7 If the resident were to develop signs and/or symptoms of UTI, a work-up including urinalysis and urine culture would be indicated.

The key infection control questions in this case relate to the need for enhanced infection control precautions for this patient. Although studies have not quantified the risk for spread of Acinetobacter in LTCFs, it is likely a similar risk as compared to the risk associated with MRSA. Since this patient is healthy and is not totally dependent on nursing home staff for help with ADL, risk for spread of Acinetobacter to other residents is small, and no special precautions are needed.1,2 Specifically, there is no need to place the resident in a private room or to restrict the resident’s movement in common areas. Also, there is no role for use of contact precautions, and there is no need to repeat a urine culture or to send a culture from another anatomic site. In addition, similar to the MRSA case, if the resident developed draining wounds or uncontrolled secretions that could not be easily contained, then the risk for spread of Acinetobacter would increase, and implementation of contact precautions and placement of the patient in a private room would be appropriate.1,2 Decolonization regimens for this organism have not been established to be effective or of any benefit and are not recommended.

Case 5

An 87-year-old man was recently transferred to a subacute setting after a prolonged Intensive Care Unit stay. His hospital course was complicated by Clostridium difficile infection. The patient responded well to a 10-day course of oral vancomycin and is no longer having diarrhea.

Key Questions:

• What type of transmission-based precautions should be followed?

• Is there a role for repeat stool testing to document clearance of toxin?

In the past decade, C. difficile infection has increased in frequency and severity, with older adults being disproportionately impacted.24,25 Infection control policies are an essential aspect of the management of C. difficile in the LTCF setting. Patients with active diarrhea related to C. difficile should be placed in contact precautions. Strict adherence to hand hygiene is also critical. In the case patient who has been treated and is not having any symptoms suggestive of treatment failure or relapse, there is no need to continue contact precautions or restrict his activities.

Testing asymptomatic patients for C. difficile toxin and repeating C. difficile testing at the end of treatment for C. difficile infection are not recommended.26 There is no role for repeating stool toxin testing at the end of therapy, especially in a patient who is doing well clinically. Furthermore, as long as patients are otherwise medically stable, there is no evidence that a stool toxin test should be required prior to accepting a patient to a nursing facility, subacute or otherwise.

In a patient with new onset of diarrhea after completing a course of therapy for C. difficile infection, the possibility of infection relapse should be considered. In this situation, testing should be based on the clinical index of suspicion. For example, in a patient with very mild diarrhea and no changes in temperature, white cell count, abdominal pain, and stool output, an approach that includes close monitoring may be reasonable instead of immediately retesting since toxin assays will likely be positive, even without clear-cut clinical disease.

The SHEA compendium currently recommends handwashing with soap and water in the case of known or potential exposure to C. difficile, rather than using waterless alcohol-based products for hand hygiene. However, this document acknowledges that this is a controversial topic, and additional research is needed to demonstrate that soap and water is preferable to alcohol-based products. Hand hygiene compliance when using traditional soap and water cleansing is historically poor and improves when alcohol-based projects are available. Alcohol is only active against the vegetative form of C. difficile and not the active spores, but studies thus far have not definitively observed an increase in the incidence of C. difficile infection after the introduction of alcohol-based products into clinical settings.27

Discussion

The previous five “real-world” cases help highlight important aspects of the recently updated SHEA/APIC guidelines for infection control practices in LTCFs. While all topics included in the guidelines are important, the cases for this article were selected based upon their frequency in LTCFs and clinical significance. Clinicians with an interest in infection control who seek additional information beyond the scope of this article have a number of available resources to choose from. SHEA and APIC have LTC committees that publish and approve infection guidelines, and publish periodic position papers related to pertinent infection control issues in LTCFs. Their websites (shea-online.org and apic.org, respectively) include several educational resources for staff education and in-services, as does the website for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (https://www.cdc.gov). There are also several excellent textbooks on infection control including one, edited by Yoshikawa and Ouslander, that focuses specifically on infection management in LTCFs.28-30

As is stated in the SHEA/APIC guidelines, infection control must balance other priorities in LTC including, most important, maximizing resident quality of life. The guidelines are meant to enhance quality of life by reducing morbidity and mortality associated with infections; however, those charged with providing care for older adults in LTCFs should be careful to recognize when infection control efforts have the potential to reduce quality of life or quality of care.

Dr. Furuno is supported by NIH Career Development Award 1K01AI071015-02. Dr. Mody is supported by K23 Career Development Award and R01AG032298 from the National Institutes on Aging, as well as UL1RR024986 Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research/Claude D. Pepper Center Pilot Grant. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to acknowledge the SHEA LTC committee for their work on the “SHEA/APIC Guideline: Infection Prevention and Control in the Long-Term Care Facility.” Dr. Furuno is at the Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore; Dr. Kaye is at the Department of Internal Medicine, Detroit Medical Center, and Wayne State University, Detroit, MI; Drs. Malani and Mody are in the Divisions of Geriatric Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, and the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) Veteran Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System, Ann Arbor, MI, and Dr. Malani is also in the Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Michigan Medical School.