Function-Focused Care for LTC Residents with Moderate-to-Severe Dementia: A Social Ecological Approach

Over one-third of long-term care (LTC) residents exhibit moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment. These residents are more likely to be inactive, require assistance with activities of daily living, have medical comorbidities, and be exposed to fewer opportunities to engage in functional and physical activities than peers who are cognitively intact or have only mild cognitive deficits. This article will discuss factors that influence the functional performance of older adults with dementia, and benefits and barriers to implementing a function-focused philosophy of care for LTC residents with dementia. Specific strategies for implementation of function-focused care with this population will be described using a social ecological framework. (Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2010;18[6]:27-32)

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other related dementia syndromes present a significant public health problem for the aging population in the United States.1 Given the progressive deterioration in cognitive and functional abilities associated with the majority of dementia syndromes, it is estimated that by the year 2020, more than 3 million older adults with moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment will require nursing home (NH) care.2-4 Even without the impact of acute illness, significant decline in functional abilities, including bed mobility, transfer, locomotion, dressing, eating, toileting, and personal hygiene, occurs within six months among NH residents with moderate and severe cognitive impairment.5

Factors That Influence Functional Performance in Older Adults with Dementia

Physical function of older adults with dementia is affected by a variety of factors such as age, gender, dementia severity, comorbid illness, mood, the care environment, and interpersonal relationships.6,7 Long-term care (LTC) staff can help to maintain or temporarily improve the physical function and physical activity of residents with dementia by motivating them to actively participate in care activities and providing them with environments that support an active lifestyle.

Unfortunately, the care of LTC residents with dementia has traditionally followed a custodial approach where staff performs necessary functional tasks for these residents regardless of resident abilities and focuses on minimizing behavioral problems during care activities.8,9 This rapid decline in functional abilities has serious implications for the amount of care needed, the increasing health risks associated with decreased mobility, the cost of providing care, and the quality of life for LTC residents with dementia.1,10,11 While we anticipate the development of interventions to more effectively treat or postpone the onset of dementia, it is important for the LTC treatment team to utilize currently available interventions that optimize or temporarily maintain functional abilities and quality of life for LTC residents with dementia.12,13

Function-Focused Care

Function-focused care is a philosophy of care that is designed to prevent or minimize functional decline and restore LTC residents to their optimal functional abilities.7,14-16 It incorporates behavior change strategies for both residents and LTC staff so that care practices move beyond the custodial management of clinical problems by getting care tasks completed to one that focuses on actively engaging residents in functional tasks and physical activity.17 A function-focused philosophy of care promotes the belief that all residents are capable of and benefit from some improvement or maintenance of functional potential, even though the function may not be entirely independent, such as passive range of motion through hand-over-hand feeding, or locomotion through self-propulsion in a wheelchair. This article will describe the benefits and barriers of function-focused care for LTC residents with dementia and will discuss suggested strategies for its implementation using a social ecological approach.

Benefits of Function-Focused Care for Residents with Dementia

Research has demonstrated the benefits of function-focused care in maintaining residents’ functional abilities, building muscle strength, improving balance, maintaining joint function, decreasing pain, improving quality of life, and decreasing caregiver burden.15,18-22 However, much of this research has been completed with LTC residents who are cognitively intact or have only mild or moderate cognitive deficits.

Despite the presence of more advanced dementia, LTC residents with moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment are able to successfully participate in and benefit from interventions to improve physical functioning relative to activities of daily living (ADL) such as eating,23,24 dressing,25 continence,26 morning care,27,28 and exercise.29,30 Function-focused care interventions have also been shown to reduce depressive and agitated behavioral symptoms among NH residents with dementia9,16,27,28,31,32 and promote sleep, which often is disrupted in older adults with dementia.33 In one study, implementation of a combined physical activity and environmental intervention resulted in significant improvements in sleep patterns among NH residents with dementia without the addition of a pharmacologic agent.33 Improving the sleep patterns of these residents may ultimately have important implications for promoting resident safety (fewer injuries from nighttime wandering) when staffing levels are typically at their lowest, although further research needs to be done in this area. In addition to resident benefits, performance of function-focused care has also been shown to benefit nursing assistants through decreased physical burden of care34 and improved knowledge, efficacy, and job satisfaction.14,35-39

Barriers/Challenges to Function-Focused Care

Functional decline is often accepted by residents, families, and caregivers as a normal consequence of aging.40 Caregiver expectations of resident inability and motivational challenges are further exacerbated when dealing with LTC residents with dementia who experience symptoms such as memory impairment, aphasia, motor apraxia, perceptual impairments, and apathy that make it more challenging for LTC staff to implement function-focused care interventions.

In addition to the cognitive, interpersonal, and motivational challenges, the presence of agitated behavioral symptoms such as verbal and physical aggression, resistance to care, sleep disturbance, and depressed mood may also adversely affect the adherence of LTC residents with dementia to interventions designed to maintain or improve functional abilities.30 When working with residents with dementia, LTC staff are often focused and rewarded for preventing or avoiding behavioral outbursts that occur during functional care activities.35,37 For example, staff who want to limit the risk of behavioral outbursts among residents with dementia may inadvertently exclude them from participation in activity programs, reinforce sedentary activities, or distract residents in order to get care activities done as quickly as possible.35,41 While this approach may help to manage agitated behavioral symptoms, it does not attempt to balance both functional and behavioral goals for residents with dementia.9,35 Ideally, interpersonal interventions that combine motivational techniques with person-centered approaches should be used to unite both functional and emotional/behavioral goals for residents with moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment.

Additional barriers to implementing new care practices in LTC settings include costs associated with the educational programs and staff resistance to behavior change. Changing care practices among LTC staff is known to be challenging, and there tends to be a drift away from participation in new programs of care over time.42,43

Despite these challenges, implementation of a function-focused philosophy of care using a social ecological approach can help to maximize functional and behavioral benefits, and minimize potential challenges for this population and their caregivers.

Implementing Function-Focused Care Using a Social Ecological Approach

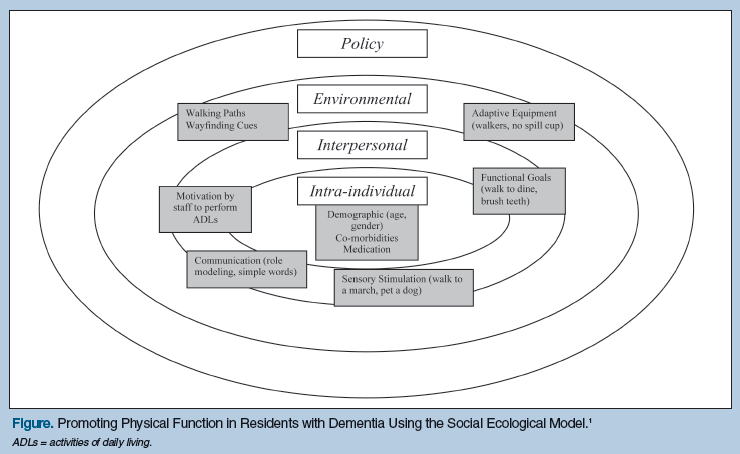

The social ecological model (Figure) addresses intra-individual (characteristics of the individual), interpersonal (relationships and social networks), environmental (physical factors), and policy factors (rules and regulations) that influence an individual’s health. The model provides a holistic framework for evaluating and changing health behaviors and has been used successfully among different populations. For example, it has previously been used in community and LTC settings to promote healthy behaviors such as exercise,44,4 to improve self-management of chronic disease,46 and to reduce the use of physical restraints.47,48 The social ecological model can easily be applied to LTC residents with dementia to help achieve the ultimate goal of keeping them actively involved in their care for as long as possible by using a strengths-based approach.

Intra-Individual Factors

Several factors at the intra-individual level should be considered and addressed in order to maximize the functional potential of LTC residents with moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment. It is recommended that a resident with a suspected dementia syndrome receive an initial medical evaluation in order to: (1) determine the most likely cause of the dementia for prognostic, treatment, and care planning purposes; (2) identify and consider management of risk factors that affect cognitive and functional abilities; and (3) identify treatable conditions that may exacerbate dementia-related symptoms that could adversely affect the resident’s function and quality of life.6,13

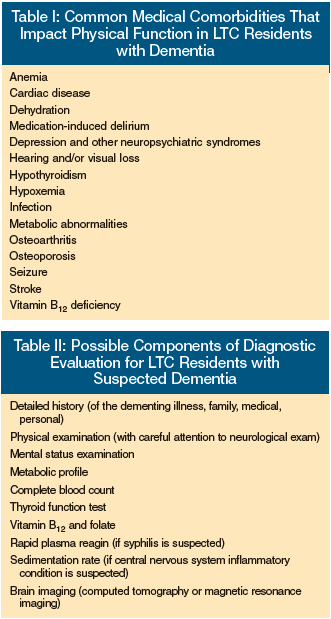

The extent of the medical evaluation is dependent upon the clinical utility of further assessment and testing, and should involve discussion with the resident, when feasible, as well as the family and the interdisciplinary treatment team. Table I identifies potentially treatable medical conditions that can impact the functional status of LTC residents with dementia. Table II outlines possible components of a medical evaluation that can be considered for these residents. Many of the components may not be indicated if: (1) the resident has a terminal condition; (2) results would not change the resident’s medical management; or (3) the work-up and treatment is felt to be burdensome or is declined by the resident or legally authorized representative.6,49 While it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss the multiple factors associated with diagnosis and treatment of dementia in the LTC setting, readers are referred to the Position Statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry Regarding Principles of Care for Patients with Dementia Resulting from Alzheimer Disease13 and the American Medical Directors Association’s Dementia in the Long-Term Care Setting: Clinical Practice Guideline6 for further information.

The extent of the medical evaluation is dependent upon the clinical utility of further assessment and testing, and should involve discussion with the resident, when feasible, as well as the family and the interdisciplinary treatment team. Table I identifies potentially treatable medical conditions that can impact the functional status of LTC residents with dementia. Table II outlines possible components of a medical evaluation that can be considered for these residents. Many of the components may not be indicated if: (1) the resident has a terminal condition; (2) results would not change the resident’s medical management; or (3) the work-up and treatment is felt to be burdensome or is declined by the resident or legally authorized representative.6,49 While it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss the multiple factors associated with diagnosis and treatment of dementia in the LTC setting, readers are referred to the Position Statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry Regarding Principles of Care for Patients with Dementia Resulting from Alzheimer Disease13 and the American Medical Directors Association’s Dementia in the Long-Term Care Setting: Clinical Practice Guideline6 for further information.

In addition to the early identification and treatment of acute and chronic medical comorbidities, LTC providers should consider potential treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors and/or memantine for LTC residents with dementia if there is a potential to stabilize or temporarily improve functional abilities, if the medication is not clinically contraindicated, and if the medication’s potential risks and benefits have been discussed with the resident (if appropriate) and the legally authorized representative.50-52 Studies have provided some evidence that cholinesterase inhibitors may reduce the rate of decline in cognition and function among individuals with mild-to-moderate AD.50,51,53,54 The only cholinesterase inhibitor that is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of more advanced AD is donepezil, which has demonstrated improvement in cognition, function, and behavior over placebo.55,56 The most common side effects associated with cholinesterase inhibitors include gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and anorexia, while, less frequently, cardiac symptoms such as irregularities in heart rate, bradycardia, and syncope may occur.57

Memantine, a NMDA receptor antagonist, may also be considered for treatment of residents with moderate-to-severe AD, and its use has demonstrated some functional, cognitive, and behavioral benefits over placebo.58-62 Memantine may be used alone and in combination with cholinesterase inhibitors, and should be based on individual assessment of potential risks (dizziness, headache, hallucinations, confusion, fatigue) and benefits.52

In order to develop appropriate function-focused goals and care plans for residents with dementia, a functional and musculoskeletal assessment should be completed to determine the underlying capabilities and restorative potential of residents. LTC staff can easily be taught to integrate a basic musculoskeletal evaluation during daily care by assessing muscle strength and range of motion.7,14,25 In addition to required LTC assessments such as the Minimum Data Set or the Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS), or required assisted living assessment forms, LTC staff may also want to utilize standardized measurement instruments to more comprehensively and quantitatively assess physical function, such as the Barthel Index,63 the Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living,64 and/or the Tinetti Performance Oriented Mobility Assessment.65 These baseline measurements can be compared with future outcome measurements to help track the effectiveness of function-focused care interventions.

Interpersonal Factors

A variety of interpersonal care approaches can be used to successfully motivate NH residents with moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment to actively participate in functional and physical activities. Some of these interpersonal care approaches include the use of: (1) modified communication strategies; (2) enhanced sensory stimulation; (3) motivation through humor and play; and (4) functional goals consistent with past life experiences. Communication strategies meant to effectively motivate residents with more advanced dementia to participate in functional and physical activities include the use of short, simple verbal cues given after gaining the resident’s attention.66 Short-term memory impairment will require the use of repetition of directions, as well as frequent encouragement and praise. Using physical gesturing and role modeling can also be helpful for residents with symptoms of receptive aphasia.16,25,36 For example, it may be helpful to seat a more independent resident with a cognitively impaired peer who needs more visual cues at mealtimes, or have a physical therapy staff member demonstrate a chair rise to a cognitively impaired resident who is working on improving balance during transfers, rather than giving extended verbal instructions. Seeing a peer or staff member perform the activity often helps the resident with moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment to model the behavior and initiate the functional activity.

When attempting to overcome apathy and passive behaviors that are seen in approximately two-thirds of older adults with dementia,67-70 it is helpful to selectively enhance sensory experiences that motivate them to actively participate in their own care.71,72 For example, the use of familiar “big band” or “swing” music with a rhythmic beat can help to motivate cognitively impaired residents to dance and move.73,74 Petting or throwing a ball for a visiting dog or cat can encourage active range of motion for residents’ arms and hands. Serving meals on dishes that provide visual and color contrast with the food may help to focus a resident’s attention on the task of eating.23,35 An exercise program that incorporates sensory stimulation in multiple domains (visual, auditory, tactile) helps cognitively impaired residents to be more engaged in physical activity.31

Humor and playful activities are often used to prevent catastrophic behavioral outbursts among cognitively impaired NH residents.70,75 This same strategy can also be employed to motivate residents with dementia to be actively involved in their own ADL.35,76 One possible strategy is to use a playful competition. For example, when assisting a resident with bathing, a nursing assistant can playfully challenge the resident to do better than the nursing assistant. While the resident washes his/her leg, the nursing assistant can wash the other, and when they are finished, the nursing assistant congratulates the resident on a job well done. While escorting a group of residents to the beauty shop, activity staff can encourage residents to walk behind their wheelchairs and provide positive feedback for everyone’s efforts. Small-group activities that are enjoyable and promote physical activity and exercise should be incorporated into the residents’ daily schedule. Some suggested activities that are appropriate for residents with moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment include indoor and outdoor hiking programs, balloon toss, beauty makeover groups that focus on grooming, movement groups, and wheelchair-cruising clubs.

In order to engage residents with dementia in functional activities, it is helpful to set functional goals that are consistent with past life experiences and that are realistic given the degree of cognitive impairment.71,77 A woman who once was a fastidious housekeeper can partner with a housekeeping staff member and/or nursing staff to help clean off tables after meals or fold towels and personal laundry. A man who previously worked the second shift in a factory and was premorbidly known to sleep late may be more independent when eating breakfast if he is able to awaken later in the morning and have flexible mealtimes.

Environmental Factors

The physical environment of LTC facilities has been identified as an important factor associated with physical health and psychosocial well-being for residents with dementia.78 Some examples of environmental interventions that can facilitate function and physical activity in these residents include outdoor access, flat walking paths with limited transitions, placement of chairs at strategic locations to allow for brief rest periods during walks, and wayfinding cues.79 Having access to mobility devices and adaptive equipment such as rolling walkers, canes, low wheelchairs with footrests removed to allow for self propulsion with feet, gait belts, grab bars, washing mitts, Velcro® closures on clothing, and adaptive eating utensils also facilitate cognitively impaired residents’ involvement in their own ADL.

Policy Factors

Policy-related issues at the LTC facility, in addition to state and national levels, are important to consider when implementing a function-focused philosophy of care because some policies may unintentionally serve as roadblocks to the promotion of physical function and activity among residents with dementia. For example, rigid regulations about scheduled mealtimes, having all residents awake and dressed by the same morning deadline, or restricted access to secure outside environments for walking may serve as barriers to promoting more independent function and physical activity in this population.

Establishing and maintaining a function-focused philosophy of care for residents with dementia is best supported by behavior change at the institutional and policy level. Behavior change is challenging, and there tends to be a drift away from functional and exercise programs over time.30,43 While all LTC staff should receive training in function-focused care so that the program is an integrated rather than designated one, it is helpful for the institution to identify and support a function-focused champion or team who would be available to help with the sustainability of a function-focused philosophy of care.14,15 The function-focused champion can provide oversight and updating of resident functional goals in conjunction with the resident, family, and interdisciplinary team, and serve as a role model, motivator, and resource person to LTC staff when they are faced with barriers and challenges.

Conclusions

LTC residents with dementia are often described and categorized by their cognitive and functional impairments. While this knowledge is important for reimbursement and care planning, LTC staff should also assess residents’ functional potential and maximize their remaining capabilities and personal strengths. Prior research testing a function-focused care intervention provided some evidence that staff was willing and able to integrate function-focused care interactions, and this approach can stabilize function and improve mood and behavior among NH residents with moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment.16 While not specific to older adults with moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment, the training manual, Restorative Care Nursing for Older Adults: A Guide for All Care Settings7and the 4 DVD training series, Restorative Care: It’s Mandated80 provide educational materials to assist LTC staff in the implementation of a function-focused care approach. Despite the chronic and progressive nature of the majority of dementia syndromes, utilizing a function-focused philosophy of care can help residents with moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment achieve the highest level of physical function possible, engage in meaningful physical activities, and optimize their quality of life.

Dr. Galik is a consultant for Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Galik is Assistant Professor, University of Maryland School of Nursing, Baltimore.

References

1. Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Chicago: Alzheimer’s Association website. https://www.alz.org/national/documents/report_alzfactsfigures2009.pdf. Accessed April 5, 2010.

2. Buttar AB, Mhyre J, Fries BE, Blaum C. Six-month cognitive improvement in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2003;16(2):100-108.

3. Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Miller SC, Mor V. A national study of the location of death for older persons with dementia [published correction appears in J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53(4):741]. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53(2):299-305.

4. Herbert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, et al. Alzheimer disease in the U.S. population: Prevalence estimates using the 2000 Census. Arch Neurol 2003;60:1119-1122.

5. Carpenter GI, Hastie CL, Morris JN, et al. Measuring change in activities of daily living in nursing home residents with moderate to severe cognitive impairment. BMC Geriatr 2006;6:7.

6. American Medical Directors Association. Dementia in the Long-Term Care Setting: Clinical Practice Guideline. Columbia, MD: AMDA; 2009.

7. Resnick B, ed. Restorative Care Nursing for Older Adults: A Guide for All Care Settings. New York, NY: Springer Publishing; 2004.

8. Bowers BJ, Esmond S, Jacobson N. The relationship between staffing and quality in long-term care facilities: Exploring the views of nurse aides. J Nurs Care Qual 2000;14(4):55-64, 73-75.

9. Cohen-Mansfield J, Jensen B. Do interventions bringing current self-care practices into greater correspondence with those performed premorbidly benefit the person with dementia? A pilot study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2006;21(5):312-317.

10. Taylor DH Jr, Sloan FA. How much do persons with Alzheimer’s disease cost Medicare? J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48:639-646.

11. Wang L, van Belle G, Kukull WB, Larson EB. Predictors of functional change: A longitudinal study of nondemented people aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1525-1534.

12. Alzheimer’s Association. Personal Care: Assisting the Person with Dementia with Changing Daily Needs. Chicago, IL: Alzheimer’s Association; 2005.

13. Lyketsos CG, Colenda CC, Beck C, et al; Task Force of American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. Position Statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry Regarding Principles of Care for Patients with Dementia Resulting from Alzheimer Disease [published correction appears in Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;14(9):808]. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;14(7):561-573.

14. Resnick B, Gruber-Baldini AL, Galik E, et al. Changing the philosophy of care in long-term care: Testing of the restorative care Intervention. Gerontologist 2009;49(2):175-184. Published Online: April 6, 2009.

15. Resnick B, Gruber-Baldini A, Zimmerman S, et al. Nursing home resident outcomes from the Res-Care Intervention. J American Geriatr Soc 2009;57(7):1156-1165.

16. Galik EM, Resnick B, Gruber-Baldini A, et al. Pilot testing of the restorative care intervention for the cognitively impaired. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2008;9(7):516-522.

17. Galik E, Resnick B. Restorative care with the cognitively impaired: Moving beyond behavior. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation 2007;23(2):125-136.

18. Resnick B, Simpson M, Bercovitz A, et al. Pilot testing of the restorative care intervention: Impact on residents. J Gerontol Nurs 2006;32(3):39-47.

19. Remsburg RE, Armacost K, Radu C, Bennett RG. Impact of a restorative care program in the nursing home. Educ Geron 2001;27:261-280.

20. Mulrow C D, Gerety MB, Kanten D, et al. A randomized trial of physical rehabilitation for very frail nursing home residents. JAMA 1994;27(7):519-524.

21. Schnelle JF, MacRae PG, Ouslander JG, et al. Functional Incidental Training, mobility performance, and incontinence care with nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43:1356-1362.

22. Heyn P, Abreu BC, Ottenbacher KJ. The effects of exercise training on elderly persons with cognitive impairment and dementia: A meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85(10):1694-1704.

23. Amella EJ. Factors influencing the proportion of food consumed by nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47(7):879-885.

24. Coyne ML, Hoskins L. Improving eating behaviors in dementia using behavioral strategies. Clin Nurs Res 1997;6(3):275-290.

25. Beck C, Heacock P, Mercer SO, et al. Improving dressing behavior in cognitively impaired nursing home residents. Nurs Res 1997;46(3):126-132.

26. Schnelle JF, Alessi CA, Simmons SF, et al. Translating clinical research into practice: A randomized controlled trial of exercise and incontinence care with nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1476-1483.

27. Rogers JC, Holm MB, Burgio LD, et al. Excess disability during morning care in nursing home residents with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 2000;12:267-282.

28. Wells DL, Dawson P, Sidani S, et al. Effects of an abilities-focused program on morning care on residents who have dementia and on caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48(4):442-449.

29. Lazowski DA, Ecclestone NA, Myers AM, et al. A randomized outcome evaluation of group exercise programs in long-term care institutions. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1999;54:M621-M628.

30. Rolland Y, Pillard F, Klapouszczak A, et al. Exercise program for nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease: A 1-year randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55,158-165.

31. Heyn P. The effect of a multisensory exercise program on engagement, behavior, and selected physiological indexes in persons with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demem 2003;18(4):247-251.

32. Williams CL, Tappen RM. Effect of exercise on mood in nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2007; 22: 389-397.

33. Alessi CA, Yoon EJ, Schnell JF, et al. A randomized trial of combined physical activity and environmental intervention in nursing home residents: Do sleep and agitation improve, J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47(7):784-791.

34. Resnick B, Orwig D, Magaziner J, Wynne C. The effect of social support on exercise behavior in older adults. Clin Nurs Res2002;11:52-70.

35. Galik EM, Resnick B, Pretzer-Aboff I. “Knowing what makes them tick.” Motivating cognitively impaired older adults to participate in restorative care. Int J Nurs Pract 2009;15(1):48-55.

36. Resnick B, Simpson M, Bercovitz A, et al. Testing of the Res-Care Pilot Intervention: Impact on nursing assistants. Geriatr Nurs 2004;25(5):292-297.

37. Resnick B, Pretzer-Aboff I, Galik E, et al. Barriers and benefits to implementing a restorative care intervention in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2008;9:102-108.

38. Resnick B, Simpson M, Galik E, et al. Making a difference: Nursing assistants’ perspectives of restorative care nursing. Rehabil Nurs 2006;31(2):78-86.

39. Weitzel T, Robinson SB, Henderson L, Anderson K. Satisfaction and retention of CNAs working within a functional model of elder care. Holistic Nurs Pract 2004;18(6):309-312.

40. Resnick B. Motivation to perform activities of daily living in the institutionalized older adult: Can a leopard change its spots? J Adv Nurs 1999;29:792-799.

41. Bates-Jensen BM, Alessi CA, Cadogan M, et al. The Minimum Data Set bedfast quality indicator: Differences among nursing homes. Nurs Res 2004;53(4):260-272.

42. Aylward S, Stolee P, Keet N, Johncox V. Effectiveness of continuing education in long-term care: A literature review. Gerontologist 2003;43:259-251.

43. Schnelle JF, Cadogan MP, Grbic D, et al. A standardized quality assessment system to evaluate incontinence care in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51(12):1754-1761.

44. Fleury J, Lee SM. The social ecological model and physical activity in African American women. Am J Comm Psych 2006;37(1):129-140.

45. Sallis J, Cervero RB, Ascher WW, et al. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annu Rev Public Health 2006;27:297-322.

46. Fisher EB. Brownson CA, O’Toole ML, et al. Ecological approaches to self-management: The case of diabetes. Am J Public Health 2005;95:1523-1535. Published Online: July 28, 2005.

47. Sullivan-Marx EM, Strumpf NE, Evans LK, et al. Predictors of continued physical restraint use in nursing home residents following restraint reduction efforts. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:342-348.

48. Wagner LM, Capezuti E, Brush B, et al. Description of an advanced practice nursing consultative model to reduce restrictive siderail use in nursing homes. Res Nurs Health 2007;30:131-140.

49. Cummings JL. Use of cholinesterase inhibitors in clinical practice: Evidence-based recommendations. Focus 2004;2(2):239-252.

50. Khang P, Weintraub N, Espinoza R. The use, benefits and costs of cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s dementia in long-term care: Are the data relevant and available? J Am Med Dir Assoc 2004;5(4):249-255.

51. Black SE, Doody R, Li H, et al. Donepezil preserves cognition and global function in patients with severe Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2007;69(5):459-469.

52. Qaseem A, Snow V, Cross T, et al; American College of Physicians/American Academy of Family Physicians Panel on Dementia. Current pharmacologic treatment of dementia: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2008;148(5):370-378.

53. Holden M, Kelly C. Use of cholinesterase inhibitors in dementia. Adv Psych Treat 2002;8:89-96.

54. Seltzer B, Zolnouni P, Nunez M, et al. Efficacy of donepezil in early-stage Alzheimer disease: A randomized placebo-controlled trial [published correction appears in Arch Neurol 2005;62(5):825]. Arch Neurol 2004;61(12):1852-1856.

55. Tariot PN, Cummings JL, Katz IR, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer’s disease in the nursing home setting J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:1590-1599.

56. Feldman H, Gauthier S, Hecker J, et al; Donepezil MSAD Study Investigators Group. A 24 week randomized double blind study of donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease [published correction appears in Neurology 2001;57(11):2153]. Neurology 2001;57(4):613-620.

57. Birks J. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(1):CD005593.

58. Reisberg B, Doody R, Stöffler A, et al; Memantine Study Group. Memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1333-1341.

59. van Dyck CH, Tariot PN, Meyers B, et al; for the Memantine MEM-MD-01 Study Group. A 24-week randomized, controlled trial of memantine in patients with moderate-to-severe Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2007;21(2):136-143.

60.Winblad B, Jones RW, Wirth Y, et al. Memantine in moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2007;24:20-27. Published Online: May 10, 2007.

61. Gauthier S, Loft H, Cummings J. Improvement in behavioral symptoms in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease by memantine: A pooled data analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008;23(5):527-545.

62. Wilcock GK, Ballard CG, Cooper JA, Loft H. Memantine for agitation/aggression and psychosis in moderately severe to severe Alzheimer’s disease: A pooled analysis of 3 studies. J Clin Psychiatry 2008;69(3):341-348.

63. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: The Barthel Index. Md State Med J 1965;14(2):61-65.

64. Katz S. Assessing self-maintenance: Activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc 1983;31(12)721-727.

65. Tinetti M. Performance oriented assessment of mobility problems in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1986;34:119-126.

66. Burgio LD, Allen-Burge R, Roth DL, et al. Come talk with me: Improving communication between nursing assistants and nursing assistants and nursing home residents during care routines. Gerontologist 2001;41(4):449-460.

67. Colling KB. A taxonomy of passive behaviors in people with Alzheimer’s disease. Image: J Nurs Scholarsh 2000;32(3):239-244.

68. Janzing JG, Naarding P, Eling P. Depressive symptom quality and neuropsychological performance in dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:479-484.

69. Kuzis GL, Sabe L, Tiberti C, et al. Neuropsychological correlates of apathy and depression in patients with dementia. Neurology 1999;52(7):1403-1407.

70. Galynker II, Roane DM, Miner C, et al. Negative symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1995;3(1):52-59.

71. Vozzella S. Sensory stimulation in dementia care: Why it is important and how to implement it. Topics Geriatr Rehab 2007;23(2):102-113.

72. Baker R, Bell S, Baker E. A randomized controlled trial of the effects of multi-sensory stimulation (MSS) for people with dementia. Br J Clin Psychol 2001;40(1):81-96.

73. Holmes C, Knights A, Dean C, et al. Keep music live: Music and the alleviation of apathy in dementia subjects. Int Psychogeriatr 2006;18(4):623-630.

74. Mathews RM, Clair AA, Kosloski K. Keeping the beat: Use of rhythmic music during exercise activities for the elderly with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2001;16:377-380.

75. Isola A, Astedt-Kurki P. Humour as experienced by patients and nurses in aged nursing in Finland. Int J Nurs Pract 1997;3(1):29-33.

76. Hendry KC, Douglas DH Promoting quality of life for clients diagnosed with dementia. J Am Psychiatric Nurs Assoc 2003;9:96-102.

77. Teri L, Logsdon RG. Identifying pleasant activities for Alzheimer’s disease patients: The pleasant events schedule-AD. Gerontologist 1991;31(1):124-127.

78. Sloane PD, Mitchell CM, Weisman G, et al. The Therapeutic Environment Screening Survey for Nursing Homes (TESS-NH): An observational instrument for assessing the physical environment of institutional settings for persons with dementia. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2002;57B(2):S69-S78.

79. Camp CJ, Cohen-Mansfield J, Capezuti EA. Use of nonpharmacologic interventions among nursing home residents with dementia. Psychiatr Serv 2002;53(11):1397-1401. 80. Resnick B. Restorative Care: It’s Mandated. 4 DVD Series. Baltimore, MD: Video Press Productions; 2003.