Difficulties in Diagnosing Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis in Older Patients

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is a highly infectious airborne disease that is classified based on disease symptoms and site of infection. When TB affects the lungs, which is the most common presentation, it is called pulmonary TB. When other parts of the body are infected, this is referred to as extrapulmonary TB. Some common sites of extrapulmonary infection include the lymph nodes, genitourinary tract, peritoneum, skin, pericardium, and meninges. We report a case of TB meningitis in an 89-year-old woman that proved difficult to diagnose, as is typical in elderly individuals. We also discuss the incidence and diagnosis of extrapulmonary TB infections in older patients and highlight the importance of early diagnosis in this population, as these patients tend to experience delays in diagnosis and, subsequently, increased morbidity and mortality, as indicated by autopsy studies.

Case Presentation

An 89-year-old woman, originally from Haiti, was admitted to the geriatrics service of an inner-city teaching hospital for a 1-week history of diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. She had presented to the emergency department 2 days earlier with the same symptoms, but her workup was unrevealing and she was discharged to home with a recommendation to take acetaminophen to reduce her pain and fever. Upon being admitted to the geriatrics service for persistent symptoms, a review of systems was positive for mild chronic headache and neck aches, but no cough, shortness of breath, neck stiffness, chest pain, or changes in cognition were evident. The patient’s medical history included chronic headaches and neck pain for 5 years, cholelithiasis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, diverticulosis, degenerative joint disease, and uterovaginal prolapse. Her regular medications included oxybutynin, omeprazole, and acetaminophen. The patient had moved to the United States from Haiti in 2005 to be with her family, and her last visit to Haiti was over 1 year before her current presentation.

The patient’s vital signs on admission revealed a temperature of 37.2°C, pulse of 95 beats per minute, blood pressure of 146/79 mm Hg, and respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute. The physical examination was notable for a diffusely tender abdomen. Cardiac, pulmonary, and neurological examinations were normal, and the patient’s family reported no changes in mental status or cognition. Abnormal laboratory findings were restricted to a serum sodium concentration of 130 mEq/L (normal, 136-142 mEq/L) and a serum alkaline phosphatase of 170 U/L (normal, 30-120 U/L). A chest radiograph revealed small bilateral pleural effusions, but was otherwise clear. During hospitalization, the patient had persistent abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, temperature spikes to 39.4°C, headache, and neck pain.

Based on the patient’s history and abdominal symptoms, the initial workup focused on an acute abdominal process. Once this was ruled out by multiple imaging studies, other causes of her fever were investigated. Blood and urine cultures and tests for various pathogens were negative, including influenza, human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, Legionella, and malaria. A transthoracic echocardiogram was negative for valvular vegetations and a computed tomography scan of the brain showed only chronic small-vessel changes. Eventually, a tuberculin skin test and a lumbar puncture were performed. The patient’s cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) revealed a protein count of 291 mg/dL (normal, 15-45 mg/dL), glucose of 11 mg/dL (normal, 40-70 mg/dL), and a white blood cell count of 216/µL (normal, <250/µL), with 17% neutrophils and 81% lymphocytes.

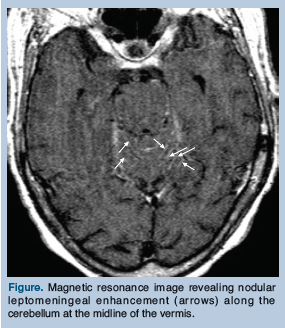

The patient’s tuberculin skin test revealed a 16-mm induration. By report, the patient had no known history of TB, and it was unclear whether she had ever received the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain demonstrated nodular leptomeningeal enhancement along the cerebellum at the midline of the vermis (Figure). Based on the CSF and MRI findings, a presumptive diagnosis of TB meningitis was made, and the patient was immediately started on the following daily medications: isoniazid, 300 mg; levofloxacin, 750 mg; pyrazinamide, 1500 mg; rifampin, 600 mg; and dexamethasone, 12 mg. Levofloxacin was chosen instead of ethambutol because of its better CSF penetration, better side-effect profile, and a lower likelihood of the patient’s TB being resistant to levofloxacin based on the pulmonary consult recommendations, although the pharmacologic literature on the best drug regimen to overcome drug resistance in TB meningitis is conflicting.

The patient’s tuberculin skin test revealed a 16-mm induration. By report, the patient had no known history of TB, and it was unclear whether she had ever received the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain demonstrated nodular leptomeningeal enhancement along the cerebellum at the midline of the vermis (Figure). Based on the CSF and MRI findings, a presumptive diagnosis of TB meningitis was made, and the patient was immediately started on the following daily medications: isoniazid, 300 mg; levofloxacin, 750 mg; pyrazinamide, 1500 mg; rifampin, 600 mg; and dexamethasone, 12 mg. Levofloxacin was chosen instead of ethambutol because of its better CSF penetration, better side-effect profile, and a lower likelihood of the patient’s TB being resistant to levofloxacin based on the pulmonary consult recommendations, although the pharmacologic literature on the best drug regimen to overcome drug resistance in TB meningitis is conflicting.

The patient’s fever resolved and she experienced significant clinical improvement with treatment. The diagnosis of TB meningitis was later confirmed with TB polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of the CSF. The patient was discharged from the hospital 11 days after admission. She continued treatment as an outpatient, receiving 4 months of dexamethasone, including taper; 2 months of levofloxacin and pyrazinamide; and 9 months of isoniazid and rifampin. Her symptoms continued to improve with therapy, and her hyponatremia was corrected within 3 months after hospital discharge.

Discussion

Extrapulmonary TB is a significant public health problem that can present a diagnostic dilemma in older patients, as our patient’s case demonstrates. We reached the diagnosis only after she presented to the hospital a second time and an extensive workup for fever of unknown origin was undertaken.

TB Prevalence In the Elderly

According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), individuals 65 years and older accounted for 2500 (10%) of all TB cases in 2008.1 With a case rate of 6.4 per 100,000, which was the highest case rate observed for any age group, it is clear that the geriatrics population makes up a large proportion of TB cases. Elderly residents in long-term care (LTC) facilities are at particularly high risk for both acquisition of new TB infection and reactivation of latent TB.2 According to previous CDC surveys, while most cases of TB in the elderly arise in community-dwelling patients, the incidence of active TB has been noted to be two to three times higher in LTC residents.3

Extrapulmonary TB has also been noted to increase in frequency with advancing age and presents an even greater diagnostic difficulty because of the nature of the organ sites involved and less familiarity with this disease among healthcare providers.2 Moreover, confirming the diagnosis is much more difficult because more invasive procedures are needed.4 The National Tuberculosis Surveillance System at the CDC has shown that there were 253,299 total TB cases from 1993 to 2006, of which 47,293 (19%) were extrapulmonary. While the incidence of extrapulmonary and pulmonary TB has decreased, extrapulmonary cases as a proportion of total TB cases have actually increased.5 This trend has been observed in the United States and other developed countries. According to the CDC, extrapulmonary TB made up 20% of total TB cases in 2008; however, the true scope of TB in the geriatrics population may not be known, as many cases are only found at autopsy.1,6 A study by Rieder and colleagues found that 60.3% of TB cases among those age 65 years or older between 1985 and 1988 in the United States were diagnosed at autopsy.6

Symptoms and Diagnosis of TB in the Elderly

Many TB cases may go unrecognized in the elderly because the disease can present atypically and subtly in this population, making it difficult to diagnose. Classic TB symptoms often are not present, as was the case with our patient. Instead, patients may report vague or unspecified problems such as fatigue, decreased appetite, low-grade fever, weakness, and cognitive changes; thus, many symptoms in older patients with active TB may be confused with a variety of clinical manifestations from other chronic diseases and comorbid conditions.2,4,7 It has also been noted that there may be substantial differences in how elderly patients with pulmonary TB present compared with their younger counterparts.8 These differences, which can be attributed to physiologic changes of aging,4 may result in a delayed diagnosis in the elderly, causing this population to experience additional morbidity and mortality.

Although TB often manifests differently in the elderly, there are no clear clinical characterizations in the literature of how various types of TB, including TB meningitis, may manifest in this population. According to data from the CDC’s National Tuberculosis Surveillance System, 5.4% of extrapulmonary TB cases were meningeal, with the majority (61%) occurring in individuals who were born in the United States.5 TB meningitis results from the rupture of a subependymal tubercle into the subarachnoid space, causing inflammation of the meninges. Subsequent arachnoiditis can lead to cranial nerve palsies and hydrocephalus. Cerebral edema is another potential complication that may lead to altered consciousness, seizures, and increased intracranial pressure.

Typically, patients with TB meningitis initially present with headache, fever, malaise, or personality changes, which may be followed by focal neurological findings, confusion, vomiting, meningismus, and, if untreated, stupor or coma.9 An example of an atypical presentation includes subtle cognitive decline that may be confused with dementia or rapid progression to clinical deterioration.9 Older patients may also present with unexplained dementia or delirium without fever or nuchal rigidity.34

Diagnosing TB meningitis typically requires a lumbar puncture; identifying lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated protein, and glucose of less than 45 mg/dL in the CSF; and consistent neuroimaging, which commonly show basal meningeal enhancement, hydrocephalus, or infarctions in the supratentorial brain parenchyma and brain stem.10 Using PCR for detecting M. tuberculosis DNA in CSF has a specificity of 98%.9

Early identification of TB meningitis is imperative because cerebral infarction is a common complication of this disease. Of patients with TB meningitis, 20% develop a focal neurological deficit and 22% to 56% have autopsy evidence of cerebral infarction.11 Infarction appears to be most common among patients with longer duration of disease. While the pathophysiology of how TB meningitis causes cerebral vessel changes is not clear, it appears that antitubercular agents and steroids are relatively ineffective in preventing the progression of cerebrovascular complications once they have begun, emphasizing the importance of early identification and treatment.11

Our patient presented with what appeared to be an abdominal process superimposed on her chronic problem of headaches and neck pains. At the time, our differential diagnosis was broad, and even in hindsight it is difficult to identify which factors most strongly suggested the patient’s eventual diagnosis of TB meningitis. Based on the literature review of incidence rates and the subtlety of presentation in elderly patients, TB meningitis should have been included in our patient’s differential diagnosis.

Conclusion

With the proportion of extrapulmonary TB cases growing, especially among the elderly, the geriatric provider needs to pay particular attention to the subtle and atypical ways this disease can present in the aging population. In many cases, such as TB meningitis, there are no clear characterizations in the literature of how older patients with the disease may present differently from their younger counterparts; thus, clinicians should include extrapulmonary TB in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with nonspecific symptoms, especially older individuals who may have multiple underlying medical problems, as early diagnosis is imperative in this population.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Han is internal medicine resident and Dr. Russell is assistant professor of medicine, Department of Medicine, Section of Geriatrics, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported tuberculosis in the United States, 2008. https://www.cdc.gov. Accessed October 13, 2010.

2. Rajagopalan S, Yoshikawa TT. Tuberculosis in long-term-care facilities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21(9):611-615.

3. Yoshikawa TT. Tuberculosis in aging adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(2):178-187.

4. Zevallos M, Justman JE. Tuberculosis in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 2003;19(1):121-138.

5. Peto HM, Pratt RH, Harrington TA, et al. Epidemiology of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the United States, 1993-2006. Clin Infec Dis. 2009;49(9):1350-1357.

6. Rieder HL, Kelly GD, Bloch AB, et al. Tuberculosis diagnosed at death in the United States. Chest. 1991;100(3):678-681.

7. Pérez-Guzmán C, Vargas MH, Torres-Cruz A, Villarreal-Velarde H. Does aging modify pulmonary tuberculosis? A meta-analytical review. Chest. 1999;116(4):961-967.

8. Korzeniewska-Kosela M, Krysl J, Müller N, et al. Tuberculosis in young adults and the elderly. A prospective comparison study. Chest. 1994;106(1):28-32.

9. Golden MP, Vikram HR. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis: An overview. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(9):1761-1768.

10. Semlali S, El Kharras A, Mahi M, et al. Imaging features of CNS tuberculosis [in French]. J Radiol. 2008;89(2):209-220.

11. Lammie GA, Hewlett RH, Schoeman JF, Donald PR. Tuberculous cerebrovascular disease: A review. J Infect. 2009;59(3):156-166.