Determination of Life Expectancy: Implications for the Practice of Medicine

Healthcare providers working in long term-care facilities are often called upon to make a judgment regarding a patient’s life expectancy. These judgments can be broadly broken down into three time frames: (1) Will a patient live long enough to benefit from a specific intervention directed at treating or preventing a disease or illness? (2) Is the patient’s life expectancy less than 6 months so that the patient can be considered for enrollment in Medicare-covered hospice? (3) Is the patient going to die so soon that family members should make arrangements now to visit the patient? This article discusses the determination of life expectancy in these three scenarios and references useful assessments for clinicians. (Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2010;18[4]:21-24)

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction

The effectiveness of many medical interventions is impacted by how long a patient is expected to live. Most healthcare providers do not apply an explicit calculation of life expectancy when deciding whether to begin a specific treatment or offer a patient a screening test. Most practitioners use implicit reasoning to make these decisions. Though physicians’ predictions of survival have been found to be highly correlated with actual survival, they have a tendency to overestimate survival.1 Medicare-covered hospice requires that a physician certify that the patient is expected to die within 6 months.2 Many healthcare providers hesitate and delay the initiation of hospice care because they don’t feel comfortable with their ability to make this determination.3 Healthcare providers are also reluctant to say when distant relatives and friends should make a final visit to a dying patient. Here again, providers are concerned that they will not make the correct judgment. Estimates of life expectancy have an important impact on medical practice in long-term care (LTC) settings, and there are now growing bodies of data that can help the healthcare provider make a more accurate determination.

Long-Term Life Expectancy (more than 6 mo)

Most healthcare providers will not prescribe bisphosphonates for the treatment of osteoporosis when a patient has metastatic lung cancer. However, should an 85-year-old patient with osteoporosis and no apparent life-threatening illness be prescribed a bisphosphonate? To answer this question from an informed perspective, the healthcare provider needs to go through several steps (discussed below): (1) calculate the patient’s life expectancy; (2) determine how long the medication needs to be given before a benefit occurs; and (3) decide whether the benefit is clinically meaningful. Side effects and costs are additional considerations. Deciding when to stop screening for a disease requires a similar analysis.

Many disease prevention guidelines now indicate that a screening test or intervention should be suspended only when the patient’s life expectancy is less than a certain number of years.4 Patients’ or their legal guardians’ wishes are a critical component of the decision-making process, especially when a patient or legal guardian decides not to proceed with a recommended treatment. In one study, a patient’s decision to have a ventricular assistive device placed to treat serious heart failure was influenced by estimated life expectancy and by predictions regarding quality of life with and without the intervention.5

Step 1. Estimating Life Expectancy

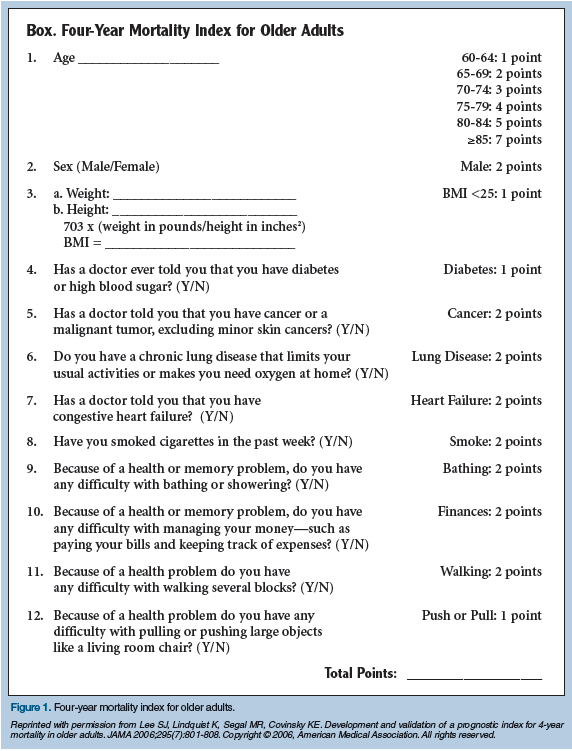

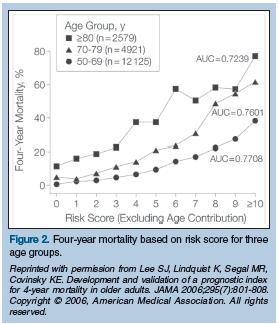

Life expectancy is affected by age, disease, and disability. Life expectancy tables list years of life expectancy at a certain age and are based on all-cause mortality.6 Although age is a strong predictor of mortality, disease is also important. Disease-related mortality is well described for some diseases, including many cancers and congestive heart failure, but not for others (eg, Alzheimer’s disease).7 Different diseases have different impacts on mortality. Lung cancer has a large impact; macular degeneration, a small impact. Frailty and disability are also important contributors to increased mortality. Dependency in dressing and toileting has been found to increase mortality.8 Lee at al9 developed a multifactor “Four-Year Mortality Index for Older Adults” that can be helpful in the clinical setting (Figure 1). The index uses age, gender, illness, and function to predict mortality. Using this Index, an 80-year-old woman with a score of 10 or above has a 4-year mortality of nearly 80% (Figure 2).

Step 2. How Long Will It Take for the Intervention to Work?

The time it takes for a medical intervention to make a meaningful difference may be very apparent (eg, use of an antibiotic to treat a urinary tract infection). Or it may be less apparent (eg, use of a bisphosphonate to reduce subsequent bone fractures). Many clinical trials that have looked at the efficacy of bisphosphonates have followed patients over a 3-year period. In one such study, women over age 80 with osteoporosis had a significantly reduced risk of a fracture if they were treated with risedronate for 3 years.10 The healthcare provider will need to be familiar with clinical recommendations based on clinical trials and the methods used to conduct the research.

The time it takes for a medical intervention to make a meaningful difference may be very apparent (eg, use of an antibiotic to treat a urinary tract infection). Or it may be less apparent (eg, use of a bisphosphonate to reduce subsequent bone fractures). Many clinical trials that have looked at the efficacy of bisphosphonates have followed patients over a 3-year period. In one such study, women over age 80 with osteoporosis had a significantly reduced risk of a fracture if they were treated with risedronate for 3 years.10 The healthcare provider will need to be familiar with clinical recommendations based on clinical trials and the methods used to conduct the research.

Step 3. Is the Outcome Clinically Meaningful?

A statistically significant outcome in a clinical trial does not necessarily translate into a clinically significant difference. Knowing the number of patients that need to be treated to prevent one bad outcome can be helpful when the clinician is deciding whether to recommend a specific intervention. In the risedronate study, 12 women needed to be treated to prevent one fracture.10 The nature of the outcome is also an important consideration: The use of bisphosphonates may reduce height loss, reduce vertebral fractures, or reduce femoral fractures, a series of events that range from lower to higher clinical significance.

Mid-Term Life Expectancy (less than 6 mo)

Before a patient can access the Medicare Hospice Benefit, a physician must certify that the patient is expected to die within 6 months. Critics have complained that healthcare providers’ uncertainty regarding a patient’s life expectancy leads to the underutilization of hospice, which results in many patients who begin hospice dying within a short time of initiating services.11 If age alone were used to determine a life expectancy of less than 6 months, only the very elderly would be enrolled in hospice. Cancer is a common reason for patients to begin hospice care, but most cancer mortality rates are listed as percentage of patients living 5 or 10 years from the time of diagnosis, and are not helpful when trying to predict mortality within 6 months. There are, however, some general and disease-specific data and prediction tools that can help the practitioner more accurately determine whether life expectancy is 6 months or less. Heart failure is a common cause of mortality for older patients.

A four-item risk score (serum urea nitrogen of 30 mg/dL or greater, systolic blood pressure less than 120 mmHg, peripheral arterial disease, and serum sodium less than 135 mEq/L) has been found to be a good predictor of 6-month mortality from congestive heart failure.12 This scale predicts that more than two-thirds of patients with three or more risk factors will die within 6 months. Dementia is a common cause of mortality for nursing home residents. The Functional Assessment Staging Test (FAST) is a measure of dementia progression (https://www.mccare.com/pdf/support/product/fast_Overview.pdf). More than two-thirds of persons with dementia at stage 7C or greater will die within 6 months.13 Stage 7C or greater is the stage at which hospice care should generally be considered. It is important to note, however, that not all patients with dementia follow the progression of disease described by the FAST.

The Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) was developed to assess patients with cancer in hospital settings.14 It has been shown to be a useful tool for predicting 6-month mortality, especially in nursing home residents. In one study, 96% of patients with a PPS score of 10-20 died within 6 months.15 All providers in LTC should be familiar with the PPS. Nursing homes should consider using this tool to help determine when palliative care and or hospice care services should be initiated.

Short-Term Life Expectancy (days)

LTC providers are often asked to predict death within several days of it occurring so that family members and friends can travel to see the patient before he/she dies. Very low scores on the PPS can indicate that death will occur within a week or less. If a patient who is already frail and ill stops taking any liquids and is not provided with artificial hydration, death can be anticipated within days, although some patients may live for a week or two. Cheynes-Stokes respiration or prolonged periods of apnea usually indicate that death for an older ill patient will occur within a day or two. It is important to point out to patients and families the difficulty of predicting death within days. It may be appropriate for family and friends to visit a dying loved one before the patient loses consciousness, which will often precede death by days or weeks. Most providers will rely on their experience to answer difficult questions regarding life expectancy. But those who are called upon to make these determinations on a regular basis should become familiar with the objective tools that can help.

Dr. Coll is Professor, Family Medicine, and Associate Director, Center on Aging, University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington.

The author reports no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Glare P, Virik K, Jones M, et al. A systematic review of physicians’ survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ 2003;327:195-198.

2. The Medicare Hospice Benefit. Advancing fair access to Medicare and health care. Center for Medicare Advocacy website. https://www.medicareadvocacy.org. Accessed February 10, 2010.

3. Brickner L, Scannell K, Marquet S, Ackerson L. Barriers to hospice care and referrals: Survey of physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions in a health maintenance organization. J Palliat Med 2004;7(3):411-418.

4. Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: A framework for individualized decision making. JAMA 2001;285:2750-2756.

5. Stewart GC, Brooks K, Pratibhu PP, et al. Thresholds of physical activity and life expectancy for patients considering destination ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant 2009;28:863-869.

6. Life expectancy tables. Annuity Advantage website. Updated November 10, 2008. https://www.annuityadvantage.com/lifeexpectancy.htm. Accessed February 5, 2010.

7. Franco OH, Steyerberg EW, Hu FB, et al. Associations of diabetes mellitus with total life expectancy and life expectancy with and without cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1145-1151.

8. Carey EC, Covinsky KE, Lui LY, et al. Prediction of mortality in community-living frail elderly people with long-term care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:68-75. Published Online: November 20, 2007.

9. Lee SJ, Lindquist K, Segal MR, Covinsky KE. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 4-year mortality in older adults [published correction appears in JAMA 2006;295(16):1900]. JAMA 2006;295(7):801-808.

10. Boonen S, McClung MR, Eastell R, et al. Safety and efficacy of risedronate in reducing fracture risk in osteoporotic women aged 80 and older: Implications for the use of antiresorptive agents in the old and oldest old. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52(11):1832-1839.

11. Schockett ER, Teno JM, Miller SC, Stuart B. Late referral to hospice and bereaved family member perception of quality of end-of-life care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;30(5):400-407.

12. Huynh BC, Rovner A, Rich MW. Identification of older patients with heart failure who may be candidates for hospice care: Development of a simple four-item risk score. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1111-1115. Published Online: May 14, 2008.

13. Hanrahan P, Raymond M, McGowan E, Luchins DJ. Criteria for enrolling dementia patients in hospice: A replication. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 1999;16(1):395-400.

14. Anderson F, Downing MG, Hill J, et al. Palliative Performance Scale (PPS): A new tool. J Palliat Care 1996;12 (1):5-11.

15. Harrold J, Rickerson E, Carroll JT, et al. Is the Palliative Performance Scale a useful predictor of mortality in a heterogeneous hospice population? J Palliat Med 2005;8(3):503-509.