Challenges in Antihypertensive Therapy in Older Persons

High blood pressure increases the risk of cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality in a continuous fashion, even in very old adults. It is also associated with dementia and physical disability. Now it seems evident that treating stage 2 hypertension can reduce CV morbidity and mortality (especially stroke), and dementia to a modest degree in older adults. Although the HYpertension in the Very Elderly Trial was the first to report benefit of antihypertensive therapy in very old adults, the benefits of pharmacological treatment of uncomplicated stage 1 hypertension and lowering blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg are not well established. In the future, trials of antihypertensive therapy should include functional outcomes, such as cognition, disability, gait impairment, and falls, which are as important as CV morbidity and mortality in older adults. This article summarizes the benefits and remaining challenges of antihypertensive therapy in older adults. (Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2010;18[1]:27-32)

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Benefits of Antihypertensive Therapy in Older Adults

High blood pressure is associated with cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality,1 dementia,2 and disability.3 A number of randomized controlled trials of antihypertensive therapy have shown a significant reduction in CV morbidity and mortality in older adults. However, the treatment and control rates among hypertensive older adults have remained poor for the past decade,4 especially so in more advanced age.5 This is in part due to uncertainties from limited evidence to guide antihypertensive therapy in older adults with complex health problems.

Overview of the Available Evidence

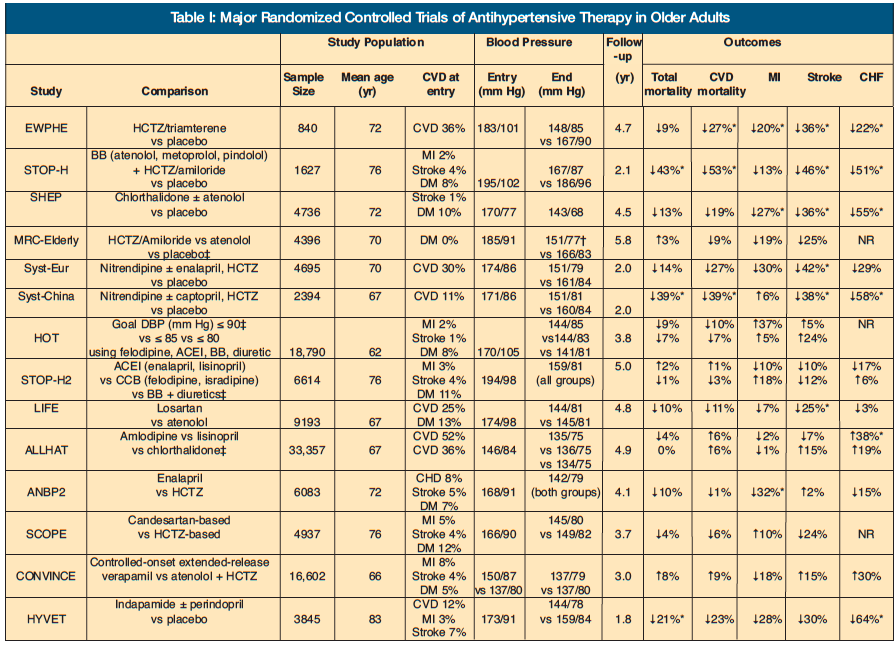

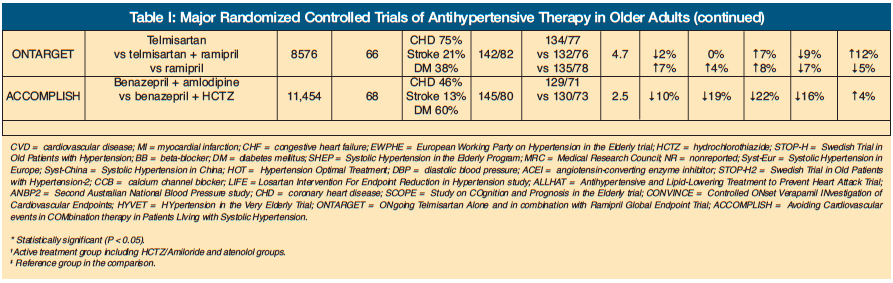

Major randomized controlled trials of antihypertensive therapy have been conducted in adults over age 50 years (Table). In general, the mean age of study samples was 62-76 years, with the exception of one trial.6 Trials before the early 1990s compared diuretics and beta blockers to placebo,7-10 whereas trials in the late 1990s compared calcium-channel blockers (CCBs) and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) to placebo.11,12 All placebo-controlled trials were conducted in stage 2 hypertension, and none achieved the target blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg. Nevertheless, many, but not all, of the trials showed significant reduction in total and CV mortality, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and congestive heart failure (CHF). The extent of risk reduction appeared greater for stroke than for MI.

Since the late 1990s, when the benefit of treatment became evident in older adults, trials compared more versus less aggressive management,13 or newer (eg, ACEIs, angiotensin receptor blockers [ARBs], CCBs) versus older agents (eg, diuretics, beta blockers).14-19 These trials were conducted in patients with stage 2 hypertension, with the exception of three that targeted high-risk patients,14,20,21 most of whom were receiving antihypertensive therapy at entry. It was also shown that the achieved blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg on treatment was associated with reduced CV events,13 and newer agents were not consistently better than older ones. In fact, thiazide was superior in preventing certain major CV events14 and, therefore, has become a preferred first-line agent.

Recent Advances

In 2008, the results of three major randomized controlled trials were published (Table). The ONgoing Telmisartan Alone and in combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial (ONTARGET)21 compared ramipril, telmisartan, and their combination in high-risk patients without heart failure. Telmisartan was as efficacious as ramipril in reducing major CV events but better tolerated due to lower rates of cough and angioedema. In contrast, the combination therapy offered no additional benefit to ramipril alone but caused more adverse events, such as syncope, hypotension, and renal impairment.

The HYpertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET)6 was a placebo-controlled trial of indapamide with or without perindopril in generally healthy adults over age 80 with stage 2 hypertension. The target blood pressure was 150/80 mm Hg, and the achieved blood pressure on treatment was 144/78 mm Hg. There was a significant reduction in total mortality and heart failure, and trends toward decreased stroke and CV mortality. Notably, some of these benefits became apparent within the first year.

The Avoiding Cardiovascular events in COMbination therapy in Patients LIving with Systolic Hypertension (ACCOMPLISH) trial20 compared benazepril plus amlodipine versus benazepril plus hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) as an initial combination therapy in high-risk patients with hypertension. There was a significant reduction in CV morbidity and mortality with benazepril plus amlodipine as compared to benazepril plus HCTZ, despite similar reduction in blood pressure between the two groups.

Evidence on Dementia

In addition to preventing CV morbidity and mortality, antihypertensive therapy appears to have a modest protective effect on dementia. In the Perindopril pROtection aGainst REcurrent Stroke Study (PROGRESS),22 perindopril and indapamide in patients with prior stroke or transient ischemic attack were associated with reduction in dementia and cognitive decline that were only associated with recurrent stroke. The benefit seemed to be the consequence of stroke prevention rather than a direct effect on cognitive function. In the Study on COgnition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE) trial, a candesartan-based regimen prevented cognitive decline as compared to a HCTZ-based regimen in older adults with low cognitive function at baseline, although overall rates of dementia and cognitive decline were similar.23 Most recently, a substudy of HYVET showed similar protective effects of antihypertensive therapy on both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in very old adults with a baseline Mini-Mental State Examination score of 26.24 However, these effects did not reach statistical significance due to a short follow-up period. A meta-analysis of four placebo-controlled trials suggested a modest benefit of reduction of dementia by 13%.24

Challenges in Antihypertensive Therapy in Older Adults

Despite high cost-effectiveness and substantial impact of antihypertensive therapy on preventing premature CV deaths and hospitalizations,25 undertreatment of hypertension remains prevalent in older adults.5 Although both provider-related (reluctance to intensify treatment) and patient-related factors (poor adherence) are related to poor hypertension control, physicians’ therapeutic inertia is thought to be the major factor.26 Here, available evidence regarding common challenges and uncertainties in antihypertensive therapy that might contribute to therapeutic inertia was examined.

Is treating hypertension as important in very old adults as in younger adults?

Physicians are less likely to change antihypertensive therapy in older patients than in younger patients.27 Possible reasons include the following: (1) the strength of association between high blood pressure and CV mortality attenuates with increasing age1; (2) high blood pressure often has been associated with better survival in adults over age 85 years28; and (3) little is known about treating high blood pressure in the very old adults. However, the population impact of hypertension is greater due to a larger number of affected individuals in older age. The paradoxical association disappeared when confounders were thoroughly adjusted for.29 In addition, when those with heart disease and stroke were excluded, a log-linear relationship between blood pressure and CV mortality was maintained in adults age 80-89 years.1 Furthermore, the benefit of blood pressure lowering on major CV events does not seem different between adults age 65 years or older and adults younger than age 65 years.30 The recently published HYVET affirms the benefit of antihypertensive therapy in adults over age 80, although study participants were generally healthy and with stage 2 hypertension.6 Nevertheless, generalizability of these findings to frail older adults with limited life expectancy, benefit of treating stage 1 hypertension, and optimal blood pressure in this age group remain unanswered.

Where should we focus: systolic blood pressure versus diastolic blood pressure?

Physicians tend to react more to diastolic blood pressure higher than 90 mm Hg than systolic blood pressure higher than 140 mm Hg, which results in suboptimal control rate of isolated systolic hypertension.26 This is partly because the historical emphasis had been on diastolic blood pressure. Control of systolic blood pressure is also harder to achieve than that of diastolic blood pressure.27 However, isolated systolic hypertension comprises the majority of untreated and undertreated hypertension in adults over age 50.31 Compared to diastolic blood pressure, systolic blood pressure is more easily and accurately measured and is a better predictor of CV events.32 From the public health perspective, focusing on a single number may reduce confusion and improve the control rate.33

Does low diastolic blood pressure pose any harm in treating isolated systolic hypertension?

Low diastolic blood pressure has been associated with increased mortality (“J-curved relationship”). This is often the reason that isolated systolic hypertension is not optimally treated. Three possible explanations exist for the J-curved relationship: (1) low diastolic blood pressure could compromise blood flow to target organs, including heart and brain; (2) it could result from increased pulse pressure, reflecting stiff large arteries from advanced vascular disease; and (3) it could be related to underlying chronic conditions.

Secondary analyses of data from randomized controlled trials have suggested that increased mortality with low blood pressure was probably related to poor health conditions, rather than treatment effects, because similar relation between blood pressure and mortality was observed between treated and untreated groups, as well as for CV and non-CV mortality.34 In the Systolic Hypertension in Europe trial, achieved diastolic blood pressure as low as 55 mm Hg was not associated with increased CV events.35 Among patients with coronary heart disease, however, achieved diastolic blood pressure lower than 70 mm Hg appeared to be associated with increased CV events.35,36 With regard to stroke, higher, not lower, systolic and diastolic blood pressure were associated with recurrent stroke in the territory of the stenotic vessel.37 Although no definitive conclusions can be drawn from the post-hoc analyses of randomized controlled trials of various antihypertensive agents, it seems prudent to intensify antihypertensive therapy with caution and close monitoring in patients with coronary heart disease and uncontrolled systolic hypertension.

Does antihypertensive therapy worsen orthostatic hypotension?

Orthostatic hypotension is a common problem that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality in older adults. Limited evidence suggests that some antihypertensive agents can worsen orthostatic hypotension. As discussed in a recent review, diuretics, beta blockers with alpha-antagonist property, and peripheral vasodilators, such as dihydropyridine-CCBs and alpha-blockers, may increase the rate of orthostatic hypotension, whereas ACEIs, ARBs, and nondihydropyridine-CCBs may improve baroreflex sensitivity and are generally considered safe.38 However, most studies were cross-sectional, involved different classes of antihypertensive agents, and measured postural changes in blood pressure and heart rate using different standards. Therefore, the existing evidence is insufficient to conclude any causal relationship.

In a study of frail nursing home residents, elevated supine systolic blood pressure before breakfast was strongly associated with orthostatic hypotension, whereas the antihypertensive agent use was not.39 Furthermore, a double-blind, randomized controlled trial examined the effect of five antihypertensive agents—CCB, beta blocker, ACEI, alpha-blocker, and thiazide—on orthostatic hypotension.40 Orthostatic hypotension was present in approximately 20% of hypertensive older adults, with higher prevalence with increasing supine systolic blood pressure. After 2 years, all treated adults showed decreased prevalence of orthostatic hypotension, although the decline was not statistically significant for alpha-blocker and thiazide. It suggests that orthostatic hypotension may improve with antihypertensive treatment and, therefore, should not deter physicians from treating uncontrolled hypertension. Initiation at a low dose and with slow titration, along with close monitoring of blood pressure change and symptoms, is necessary.

Is one antihypertensive regimen better or worse than others in treating older adults?

Although the use of older antihypertensive agents, such as beta blockers and diuretics, has been advocated in treating older adults, a recent meta-analysis did not find strong evidence that the effects of different classes of antihypertensive agents vary significantly between younger and older adults.30 As discussed earlier, randomized controlled trials that compared older and newer antihypertensive agents in older adults did not consistently show the reduction of major CV events with newer agents (Table). Overall, lowering blood pressure seems more important than which antihypertensive regimen to use.

Recently, the role of beta blockers in treatment of uncomplicated hypertension has been called into question. Beta blockers, especially atenolol, are ineffective in preventing all-cause mortality and myocardial infarction as compared to placebo.41,42 They provide 16-22% reduction in stroke risk as compared to placebo, but this degree of reduction is lower than the reduction seen with other agents, such as CCBs, ACEIs, and ARBs.41 Possible explanations for lack of efficacy include failure to lower central aortic pressure, less efficacy on regression of left ventricular hypertrophy and endothelial dysfunction, increased risk for new-onset diabetes, and poor tolerability due to side effects (ie, weight gain and decreased exercise tolerance). Some evidence suggests that a newer beta blocker with vasodilating property, nebivolol, may be as efficacious and well tolerated as other antihypertensive agents, with favorable effects on arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction; however, long-term data on clinical CV outcomes are lacking.43 Based on these evidences, beta blockers should not be used as a first-line agent for uncomplicated hypertension but remain an effective agent for heart failure, prior MI, acute coronary syndrome, stable angina, prevention of perioperative cardiac complications, or hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy.44

In addition, there is some evidence that ARBs may confer additional benefit of stroke prevention beyond blood pressure lowering by modulating the renin-angiotensin system. Two types of angiotensin II receptors have been implicated to explain this neuroprotective benefit.44,45 The type 1 receptors, expressed in various adult tissues, induce vasoconstriction, sodium and water retention, smooth-muscle proliferation, and vascular endothelial damage. In contrast, the type 2 receptors, expressed in fetal tissues and upregulated in ischemic brain tissue, modulate the type 1 receptor activity, reduce inflammation and neuronal apoptosis, and induce vasodilation, thereby mediating neuroprotective effect. It has also been suggested that agents that increase angiotensin II level (ARBs, diuretics, and long-acting dihydropyridine-CCBs) may provide greater reduction in stroke than do agents that reduce angiotensin II level (beta blockers and ACEIs; 33% vs 13% reduction as compared to placebo).46 Furthermore, the risk of stroke was lower with losartan (vs atenolol),16 candesartan (vs HCTZ),18 and eprosartan (vs nitrendipine),47 despite similar reduction or small difference in blood pressure. This benefit of ARBs is believed to be mediated from blockade of the type 1 receptors and angiotensin II upregulation with increased type 2 receptor activity. However, the recently published ONTARGET study did not find a significant reduction in stroke with telmisartan as compared to ramipril (4.3% vs 4.7%).21 Therefore, the neuroprotective benefit of antihypertensive agents needs to be further examined in future trials.

Conclusions and Remaining Challenges

High blood pressure is associated with CV morbidity and mortality in a continuous fashion, even in very old adults; it is also associated with dementia and disability. Now it seems evident that treating stage 2 hypertension can reduce CV morbidity and mortality (especially stroke) and dementia to a modest degree in older adults. In treating hypertension, systolic blood pressure should be the target of therapy, and diastolic blood pressure can be reduced as low as 55 mm Hg without significant harm to control systolic blood pressure. However, careful monitoring is required for patients with coronary heart disease and diastolic blood pressure below 70 mm Hg. In older adults with orthostatic hypotension, initiation at a low dose and slow titration of antihypertensive agents should be attempted, because treatment of uncontrolled hypertension may improve orthostatic hypotension. In general, lowering blood pressure is more important than which regimen to use. However, beta blockers are no longer a preferred agent for uncomplicated hypertension due to lack of mortality benefit and suboptimal stroke reduction. There is some evidence that ARBs may confer neuroprotective benefit beyond blood pressure reduction.

Although HYVET was the first trial to report benefit of antihypertensive therapy in very old adults, the benefits of treating uncomplicated stage 1 hypertension with antihypertensive medications and lowering blood pressure below 140/90 mm Hg are not well established. Whether antihypertensive agents cause incident orthostatic hypotension needs more data. In the future, trials of antihypertensive therapy should include functional outcomes, such as cognition, disability, gait impairment, and falls, which are as important as CV morbidity and mortality in older adults.

The author reports no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Kim is supported by the John A. Hartford Center of Excellence Research Fellowship Award at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Kim is in the Division of Gerontology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.