Breast Cancer Screening with Mammography in Vigorous, Average, and Frail Older Women

No randomized controlled trials (RCTs) exist for any cancer screening test in adults over age 75 years. While there is RCT evidence from younger adults, it is difficult to extrapolate to older patients. Even if RCTs for patients over age 75 were available, they would likely have been conducted in relatively healthy and vigorous populations and would have limited or no applicability to patients with either substantial comorbidities or decreased functional status. Expert groups have proposed guidelines for cancer screening in older adults, but few of these consider functional status or comorbidities. This article reviews the evidence behind breast cancer screening with mammography for older women at average risk. The authors propose a method combining age with functional status/comorbidities in helping patients and their providers decide whether to access this Medicare-funded screening test. (Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2009;17[10]:24-31)

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction

Breast cancer incidence rises steadily with age; the other major risk factor for breast cancer is a family history of the disease. Other risk factors include biopsy-confirmed atypical hyperplasia and first childbirth after age 30. Breast cancer incidence may be lower among women of Hispanic or Asian ethnicity, but these women have lower rates of mammographic screening and also tend to be diagnosed with breast cancer at later stages. Therefore, mammographic screening recommendations do not differ by the ethnicity of the woman.1

No randomized controlled trials (RCTs) exist for any cancer screening test in adults over age 75 years. While there is RCT evidence from younger adults, it is difficult to extrapolate to older patients. Even if RCTs for patients over age 75 were available, they would likely have been conducted in relatively healthy and vigorous populations and would have limited or no applicability to patients with either substantial comorbidities or decreased functional status—in other words, to typical patients.2

Expert groups have proposed guidelines for cancer screening in older adults, but few of these consider functional status or comorbidities.3 This article reviews the evidence behind breast cancer screening with mammography for older women at average risk. We propose a method combining age with functional status/comorbidities in helping patients and their providers decide whether to access this Medicare-funded screening test.

Framework for Screening

In a classic article, Walter and Covinsky4 articulated a framework of five steps for deciding whether to pursue cancer screening in older adults (Table I). We use their methodology to present a detailed argument on whether to screen older women for breast cancer using standard mammography.

In a classic article, Walter and Covinsky4 articulated a framework of five steps for deciding whether to pursue cancer screening in older adults (Table I). We use their methodology to present a detailed argument on whether to screen older women for breast cancer using standard mammography.

Step 1: Estimate life expectancy (Table II).5

For women over age 65 years, there is little difference in life expectancy by race. Notice that three life expectancies are presented at each age—the 25th percentile, the 50th percentile, and the 75th percentile. Women at or above the 75th percentile are the healthiest quartile of women at that age (vigorous). Women at the 50th percentile are in average health, and women at or below the 25th percentile are the frailest one-fourth of the population.

For example, a healthy 85-year-old woman with hypothyroidism and normal cognition who is independent in activities of daily living is vigorous, so one would use the 75th percentile. Her life expectancy is 9.6 years. At the other extreme, consider a 70-year-old woman living in the nursing home with congestive heart failure (CHF) and oxygen-dependent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). One would choose the 25th percentile for this frail woman, and her life expectancy from the chart is 9.4 years. Actually, she is well below the 25th percentile, so her life expectancy is considerably less. This method of estimating life expectancy demonstrates that comorbidity and functional status are more predictive than chronologic age.

Step 2: Estimate risk of dying from breast cancer in the older woman.

For example, a vigorous 85-year-old woman has a 1.9% lifetime chance of dying from breast cancer, while a frail 70-year-old woman has a 1.2% chance.4 Notice in this example that the older patient may be more likely to benefit from mammography than the younger woman.

Step 3: Estimate the effect of screening on the cancer death rate.

If every breast cancer was detected by screening and cured without complication, the benefit of screening would equal the risk of dying from that cancer. However, mammography is much less than 100% effective because it may miss early cancer, it may preferentially detect advanced cancer, and it may detect indolent cases that would never have led to symptoms during life. RCTs of mammographic screening in women age 50-70 years demonstrate a 26% reduction in the risk of dying from breast cancer. The benefit on breast cancer mortality takes at least 5 years, perhaps even 7-10 years, to take effect.4

Let’s calculate the risk of breast cancer death in an 80-year-old woman with a life expectancy of 9.1 years (50th percentile), who has annual mammography, taking into account a 5-year lag before mortality reduction begins. From cancer surveillance studies, we know that breast cancer mortality from age 80-85 years is 157/100,000/year x 5 years = 0.79%, or just under 1%. From age 85-89.1 years (the average number of years of life she has remaining), the breast cancer mortality rate is 200/100,000/year x 4.1 years = 0.84%.

The risk of breast cancer mortality in the unscreened woman is 0.79% + 0.84%, or 1.63%. Regular annual mammography from age 80-85 years will not reduce breast cancer mortality in the first 5 years (there is a 5-year lag), but it does reduce breast cancer mortality by 26% after that. So if we reduce the 0.84% breast cancer mortality from age 85-89.1 years by 26%, this is a reduction of 0.26 (0.84%) or 0.21%, to a new predicted cancer mortality of 0.63%. If we add these risks (breast cancer mortality from age 80-85 yr, plus the 26% reduction in breast cancer mortality from age 85-89.1 yr), we get 0.79% + 0.63%, or 1.42%, which is the average lifetime risk of breast cancer mortality in a population of screened women.

The absolute risk reduction in breast cancer mortality in the screened population, as compared with the unscreened populations, is (rate in unscreened – rate in screened) = 1.63% – 1.42%, or 0.19%, or about 1 in 500. That is, if 500 80-year-old women in average health undergo 5 years of annual mammography, one death from breast cancer will be prevented. As life expectancy decreases, the number needed to screen rises dramatically.

Step 4: Consider potential harms of screening.

In the case of mammography, there are complications of additional procedures, including biopsy, surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and follow-up. There is also the treatment of “unimportant” cancers, cancers that would never have become symptomatic or caused substantial problems in the remainder of the woman’s life. In women with dementia, mammography may be very difficult and likely misunderstood as a painful attack.

Women over the age of 70 years have abnormal mammograms in about 7-9% of cases, of which about 85% are false positives. In addition, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is found in 0.1% of 70-84-year-old women undergoing mammography, but only 7-25% of these women will progress to invasive cancer over the next 5-10 years.4 If women have regular mammographic screening over 10 years, one-third will have at least one abnormal study, which usually leads to biopsy.6

The negative consequences of screening frail older women were vividly demonstrated in the On Lok community (predecessor of the Medicare Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly [PACE]), whose participants were required to undergo mammography at least once, regardless of frailty.7 All of these women were frail and nursing home–eligible. Thirty-eight of 216 screened women (17%) had an abnormal mammogram, and 32 of the women/families agreed to evaluation. Of these 32, 28 biopsies were negative. In four women, the biopsies were positive for cancer (true positives); three had stage 1 invasive breast cancer, and one woman had DCIS. All four of these women underwent surgical treatment, but two died within 2 years of unrelated illness after suffering complications of surgery. At most, two out of 216 (1%) had any potential benefit.7 Considering the marginal benefit of mammographic screening in the very old and frail and the chance of harm for most of these women, mammography is likely to provide a net harm.8-11

Step 5: Incorporate the values and preferences of the patient into the screening decision.

A negative mammogram may provide “peace of mind” to one woman, but this is not possible if the woman has severe dementia. Patients who would not want or could not undergo further workup should not be screened.

Expert panels that make recommendations for breast cancer screening disagree about when to stop cancer screening in older adults (Table III).12-18 Only one of the RCTs of mammographic screening included women over age 70 years, and that study did not show a breast cancer mortality reduction in women age 70-74 years.16 None of the randomized trials of mammography included women over the age of 75 years. However, on average, older women present with larger tumors, and since their breasts are less dense, mammography is actually more sensitive in detecting cancer. In addition, breast cancer in older women is more likely to be hormone-receptor positive, thus with a better prognosis.16 Further, although there are no RCTs of mammographic screening in women over the age of 75 years, cohort studies do suggest that screened women may have more early-stage disease and lower breast cancer mortality, although bias may explain these results.16,18 Screening mammography rates decline with age, and non-white women receive mammography less frequently at all ages and degrees of health status.19,20

The Effects of Age, Race, and Comorbidity

At age 65 years, white women of average health have an average life expectancy of 19.2 years, versus 17.7 years for black women, but this difference narrows to zero by age 81 years, after which older black women have a slight survival advantage. Therefore, we suggest using the same life expectancy table for both black and white older women when considering breast cancer screening.5

At age 65 years, white women of average health have an average life expectancy of 19.2 years, versus 17.7 years for black women, but this difference narrows to zero by age 81 years, after which older black women have a slight survival advantage. Therefore, we suggest using the same life expectancy table for both black and white older women when considering breast cancer screening.5

An interesting advance is the development of outpatient clinical “glidepaths,” or evidence-based recommendations, based not just on chronologic age but also life expectancy and functional status. This group divides older adults into robust, frail, moderate dementia, and end-of-life categories.21

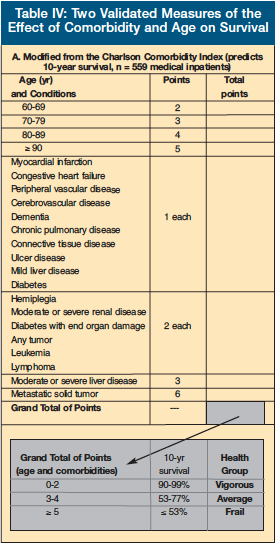

The Charlson Comorbidity Index (Table IV-A) was developed from 1-year mortality data based on hospitalized patients and predicts 10-year survival based on the presence of certain medical conditions.22 First used as a guide to treating cancer in older adults, its use has also been validated for many other medical conditions. The Charlson Comorbidity Index assigns different “weights” to various medical conditions.

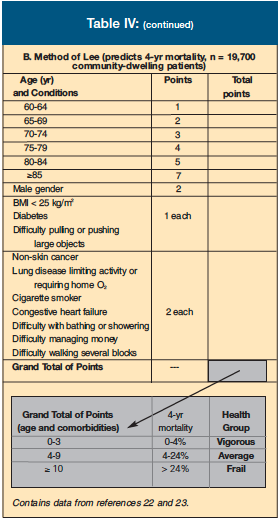

Lee et al23 followed 19,000 non-institutionalized adults over 50 years of age and developed a prognostic index for mortality (Table IV-B). This group identified comorbidities, behaviors, and functional measures that were independent predictors for mortality, along with three minor predictors.

It is interesting that functional limitations, regardless of the source of those limitations, have such a powerful effect on mortality. For example, a 70-year-old woman with none of the above risk factors has a 4-year mortality rate of only 3%. If this woman has oxygen-dependent COPD, CHF, and has trouble walking several blocks, her 4-year mortality rate rises to 24%.

Conclusions

Rigorous RCT evidence supports mammographic screening of women up to age 70 years. The clinician can use common sense as well as Tables II and IV to help determine whether an older woman who is considering cancer screening can be best classified as vigorous, average, or frail. This classification is clearly subjective, and more work is needed to more accurately delineate these sub-groups. One weakness of the Charlson and Lee models is that it is difficult to classify any adult over age 70 or 80 years as vigorous.

Rigorous RCT evidence supports mammographic screening of women up to age 70 years. The clinician can use common sense as well as Tables II and IV to help determine whether an older woman who is considering cancer screening can be best classified as vigorous, average, or frail. This classification is clearly subjective, and more work is needed to more accurately delineate these sub-groups. One weakness of the Charlson and Lee models is that it is difficult to classify any adult over age 70 or 80 years as vigorous.

After categorizing the patient as vigorous, average, or frail, the clinician should consult Table V, which provides general advice on whether to advise cancer screening with mammography. This table is divided into 5-year increments, starting at age 65, and then further stratified by the descriptors vigorous, average, and frail, which roughly correspond to 75th, 50th, and 25th percentiles of life expectancy.

Suggestions for cancer screening in this table fall into three categories: the light gold blocks represent women who are most likely to benefit from mammography; the light blue blocks represent combinations of age and function/comorbidity where mammographic screening should not be recommended (one could either simply not bring it up, or one could recommend against the screening test); and the darker gold zones represent where the risks/benefits of cancer screening seem unclear, where the clinician might explore the option more fully with the older woman.

These suggestions take into consideration the life expectancy of the patient in each individual cell of the table, the effectiveness of the screening test, and other considerations. For mammography, we assume that an older woman must live 5-7 years to benefit from screening. Presented with a vigorous 82-year-old woman, recommend screening mammography. For a frail 68-year-old woman, screening with mammography is not strongly recommended, but it would be reasonable to consider this test, depending on her comorbidities, functional limitations, and preferences. Most women living in nursing homes would be considered frail.

These considerations are clearly subjective, and clinicians should make decisions about screening in an individualized fashion. In addition, these recommendations apply to average-risk patients, not to those older adults who may have risk factors for cancer, and therefore may theoretically have more to gain from cancer screening.

Finally, we must be honest that under the best of circumstances, breast cancer screening in the older adult has limited effectiveness. Evidence suggests that mammographic screening for breast cancer has only modest effects on the quality of the older woman’s life. As cancer screening has substantial harms and costs, it should always be part of an overall comprehensive approach, not an automatic decision.3

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Ackermann is Professor and Director, and Dr. Baralatei is Assistant Professor, Division of Geriatrics, Department of Family Medicine, Mercer University School of Medicine, Macon, GA.