Bisphosphonates: Controversies and Clarifications

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a common condition among nursing home residents. About 85% of new nursing home residents have been reported to have osteoporosis.1 Furthermore, nursing home residents are at a high risk of developing osteoporosis-related fractures. Hip fractures are the most common osteoporotic fractures among this patient population, with an annual rate of 5% to 6%.2 Bisphosphonates are widely prescribed for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis.3 Four bisphosphonates are currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, and zoledronic acid. This brief report addresses a couple of the controversies that surround the use of bisphosphonates.

Controversy #1: Concerns About Safety of the Long-Term Use of Bisphosphonates

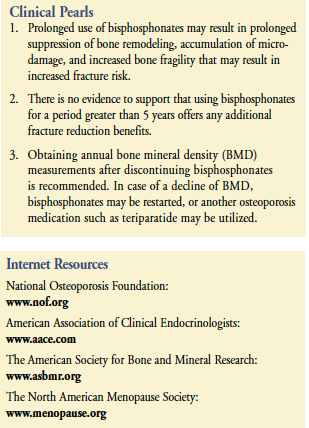

Bisphosphonates exert their effect on bone by inhibiting osteoclasts and bone resorption. In doing so, they also inhibit bone remodeling.3 Bone continuously sustains microdamage as a result of everyday activities. Bone remodeling is important to remove microdamaged bone and replace it with new bone. Prolonged suppression of bone remodeling will result in the accumulation of damaged bone. This will ultimately lead to the development of weakened bone that is more susceptible to fractures.4 Animal studies have shown that administering bisphosphonates in high doses to animals resulted in accumulation of microdamage.5 More recently, a group of researchers from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School reported nine patients who sustained nontraumatic nonspinal fractures after 3-8 years of alendronate therapy.6 Bone biopsies in these patients revealed severe reduction in bone formation rates and resembled the “adynamic bone disease” that was described in patients with chronic renal failure. Similar cases were later reported by other investigators.7 The suppression of bone remodeling and the occurrence of adynamic bone disease are now recognized as potential complications of prolonged bisphosphonate use.8

Osteonecrosis of the jaw is another potential complication of long-term bisphosphonate use. Woo and colleagues9 summarized 368 reported cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw that were linked to bisphosphonate use. Ninety-four percent of all cases occurred after receiving intravenous bisphosphonates (pamidronate and zoledronic acid). The majority (85%) of subjects had a diagnosis of multiple myeloma or metastatic breast cancer. Few were taking oral bisphosphonates for osteoporosis or Paget’s disease of the bone. Sixty percent of the cases occurred after tooth extraction. The remaining cases often involved a source of local trauma (eg, wearing dentures). Osteonecrosis of the jaw manifested as exposure of a portion of the bone in the mandible (65%), maxilla (26%), or both (9%).

The risk of developing osteonecrosis of the jaw increases with the prolonged use of bisphosphonates.10 Suppression of bone remodeling secondary to bisphosphonate use is the likely mechanism involved.10 The American Dental Association recommends that all individuals should receive dental evaluation before starting intravenous bisphosphonate therapy. It also recommends that individuals who received oral bisphosphonates for a period greater than 3 months should undergo dental evaluation. The initial dental evaluation mainly focuses on eliminating potential sites of infection. Follow-up appointments every 3-6 months are also needed for hygiene maintenance.10

Controversy #2: The Optimum Duration of Bisphosphonate Use

Published pharmacokinetic data indicate that bisphosphonates remain in the bone matrix for many years. For example, the terminal half-life of alendronate is about 10.5 years.8 This led to the hypothesis that patients with osteoporosis may only need to take a bisphosphonate for a few years, as the medication might have a long-lasting effect on bone. This hypothesis was tested in the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term EXtension (FLEX), which examined the effects of discontinuing alendronate treatment after 5 years versus continuing treatment for 10 years in 1099 postmenopausal women.11 Data from FLEX showed no significant difference in cumulative risk of nonvertebral fracture rate (relative risk [RR], 1.00; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.76-1.32)  between individuals who discontinued alendronate at 5 years (18.9%) as compared to those who continued it for 10 years (19%). The risk of clinically recognized vertebral fractures was significantly lower (RR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.24-0.85) in the group that continued alendronate for 10 years (2.4%) as compared to the group that stopped alendronate after 5 years (5.3%). However, there was no significant difference between both groups in the rate of morphometric vertebral fractures (11.3% for the 5-yr group and 9.8% for the 10-yr group; RR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.60-1.22). Findings from FLEX suggest that 5 years may be sufficient time to incur maximum fracture benefit from alendronate therapy. Similar studies for risedronate, ibandronate, and zoledronic acid are not yet available.

between individuals who discontinued alendronate at 5 years (18.9%) as compared to those who continued it for 10 years (19%). The risk of clinically recognized vertebral fractures was significantly lower (RR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.24-0.85) in the group that continued alendronate for 10 years (2.4%) as compared to the group that stopped alendronate after 5 years (5.3%). However, there was no significant difference between both groups in the rate of morphometric vertebral fractures (11.3% for the 5-yr group and 9.8% for the 10-yr group; RR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.60-1.22). Findings from FLEX suggest that 5 years may be sufficient time to incur maximum fracture benefit from alendronate therapy. Similar studies for risedronate, ibandronate, and zoledronic acid are not yet available.

Obtaining annual bone mineral density (BMD) measurements after discontinuing bisphosphonates is recommended. In case of a decline of BMD, bisphosphonates may be restarted, or another osteoporosis medication such as teriparatide may be utilized.

Conclusion

The growing concern over the long-term safety of bisphosphonates combined with the lack of evidence of any fracture reduction benefits after 5 years of therapy would constitute a reasonable argument for limiting the duration of bisphosphonate therapy to 5 years.

Dr. Kamel has been on the speakers bureaus for GlaxoSmithKline plc, Roche, and Eli Lilly and Company, and was a paid consultant/advisory board member for Roche, Eli Lilly and Company, and Procter & Gamble. Dr. Kamel is Associate Clinical Professor of Geriatrics, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

__________________________________

Corrections

In the article “Treatments for Depression in Older Persons with Dementia” that appeared in the February 2009 issue of the Journal, in the section entitled “Pharmacologic Treatment of Depression in Dementia”, subsection “Antidepressants,” buspirone is referred to as an antidepressant. Specifically, buspirone is classed as an anxiolytic with serotonergic or antidepressant activity (see Buhr & White, 2006, referenced in original article). Although buspirone has demonstrated some efficacy in trials and clinical use for both primary and augmentative treatment of depression, it is currently FDA-approved only for the treatment of anxiety disorders.

In the same section, the paragraph titled “Anticholinergics” should be titled “Cholinergics.” The term “anticholinergics” is also substituted incorrectly for “cholinergics” in the final sentence of the final sentence in the section titled, “Antidepressants,” and in the first paragraph of the final “Summary” section. The authors apologize for these errors.