Alternative Drug Therapies in LTC Facilities: A Guide to Definition, Policies, and Procedures

Herbal and related alternative drug therapies have gained increasing popularity among the public in general, and the elderly in particular.1,2 According to the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, complementary and alternative medicine is a group of diverse medical and healthcare systems, practices, and products that are not generally considered a part of conventional medicine.3 While a growing body of data exists on the effectiveness or lack thereof of alternative therapies,4,5 these therapies are not usually taught in U.S. medical schools, nor are they generally available in U.S. hospitals.

Long-term care (LTC) facilities present a special challenge in this regard, as facilities need to consider their duty to protect residents and facility liabilities while balancing the need for patients to remain empowered to exercise their rights to self-determination and choice.

In this article, a general policy for the use of alternative products in LTC facilities is presented. The policy was formulated by the author, with input from administration and legal counsel, while serving as a full-time medical director in a nursing facility. The policy offers a framework from which administrators and medical directors in other facilities may develop their own policies. Rationale for and comment on various statements are indicated in italics. The author proposes the definition below for alternative drug therapy to define products but not alternative healthcare systems or practices.

Alternative Drug Therapies: Definition and Background

A substance with purported health benefits is considered to be an alternative drug therapy (ADT) when:

1. Its use is not approved or regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations, and

2. Its use for a specific condition(s) has not been recommended by a governmental agency such as, but not necessarily limited to, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), or Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and

3. No general standard exists in the medical community governing its use.

For a substance to be considered an ADT, all three above criteria must be met.

Additional ADT Considerations:

ADTs include, but are not necessarily limited to, substances for oral ingestion, enteral administration (ie, potential administration per rectum or via gastrostomy tube), inhalation, or topical or nasal application.

ADTs are commonly available for purchase without prescription in pharmacies, supermarkets, and general nutrition stores and include, but are not necessarily limited to, substances such as St. John’s wort, ginkgo biloba, saw palmetto, echinacea, megavitamin and mineral supplements, and various other herbs and extracts.

ADTs do not include drugs and biologics undergoing clinical investigation when such use is governed by the applicable laws of the FDA or other governmental agency (ie, the policy does not pertain to residents who may be enrolled in FDA-approved clinical trials since criteria 1 above would not be met).

POLICIES:

1.The facility and its medical staff have the ethical, legal, and professional duty to provide care consistent with governmental regulations and community standards.

2.The facility and its medical staff have the ethical, legal, and professional duty to protect its residents/patients from harm (primum non nocere).

3.The facility and its medical staff have no ethical, legal, or professional obligation to provide its residents/patients with ADTs.

4. The facility and its medical staff, family members, and surrogates recognize that the facility is the home for those admitted for LTC.

5.The facility and its medical staff recognize the resident’s right of self-determination and the rights of the legally designated individual to exercise these rights on behalf of the incapable resident.

6.It is the policy of the facility (as well as a matter of regulation) that conventional drug treatments, including drugs that are FDA-approved but available without prescription, require a physician (or legally authorized practitioner) order. (The intent is to differentiate over-the-counter products approved by the FDA, and for which the healthcare provider assumes responsibility for its administration [eg, acetaminophen, omeprazole, cimetidine] as distinct from ADTs for which the prescriber does not implicitly recommend nor assume responsibility for the outcome of its use.)

PROCEDURES:

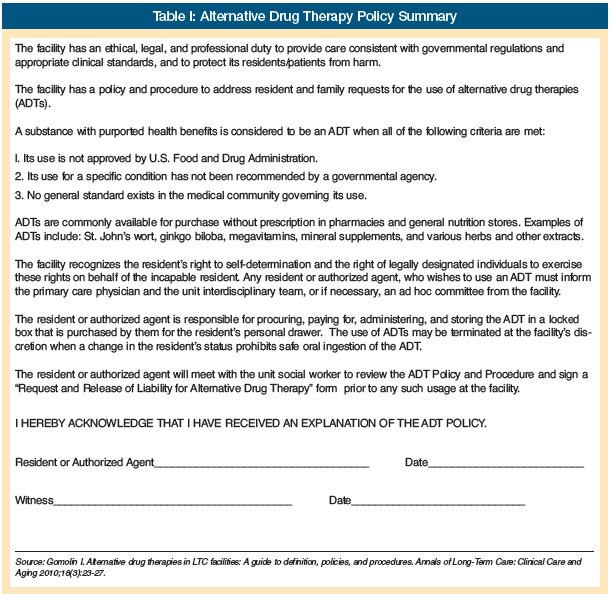

1.Prospective applicants and/or authorized agents are informed of this policy during the intake interview prior to admission. They will receive a summary of the “Alternative Drug Therapy Policy” and sign the acknowledgment that they have received an explanation of this policy (Table I). (This will avoid the situation whereby a novel ADT is introduced to the market and/or a new request is obtained for an already established resident; similarly, a facility may wish to have an acknowledgment signed by prospective applicants indicating that the facility does not administer ADTs.)

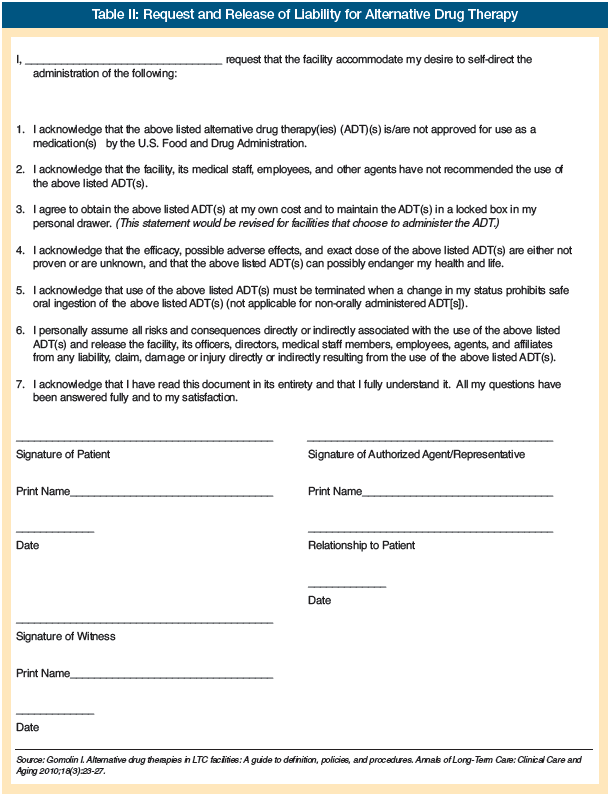

2.Prior to any ADT usage at the facility, both the resident, if capable, and the authorized agent will meet with the unit social worker to review the ADT policy and will sign a “Request and Release of Liability for Alternative Drug Therapy” form (Table II).

3.Residents who desire ADT are evaluated by the primary care physician and specialty consultation, if appropriate.

4.ADT can be considered (ie, permitted) when

I. a. no conventional drug treatment exists for the indication/condition, or

b. previous or current conventional drug treatment has failed to produce the desired effect, or

c. previous conventional drug treatment has caused untoward reactions, or

d. the resident has been receiving the ADT chronically prior to admission

and

II. The ADT is commercially available in the community. (This purposefully excludes ADTs available from foreign countries, as quality control may not be ascertainable.)

and

III. There is a low likelihood of significant harmful side effects associated with the ADT.

and

IV. The ADT is proposed for use according to the label but no greater than recommended doses, where labeling exists.

5. An ad hoc committee consisting of the primary care physician, medical director, director of pharmacy, administration, nursing, social worker, as necessary, will be convened, if the primary care physician and unit interdisciplinary team have not been able to satisfy the resident and/or designated representative with respect to the request for the ADT. (The intent is not to burden the entire team in the decision to provide the ADT unless necessary.)

6. The resident or authorized agent is responsible for procuring, paying, and administering ADTs. (Some facilities may wish to assume responsibility for administering the ADT to those residents who cannot self-administer medications, but this does not imply an obligation to pay for substances that are not covered by medication insurance plans.)

7. For residents who self-administer medication, the resident or authorized agent must agree to keep the ADTs in a locked box in the resident’s personal drawer (to prevent access to these ADTs by other residents).

8. For residents whose nutritional intake is via NG/G/J-tube (nasogastric/gastrostomy/jejunostomy tube), Pharmacy will dispense the ADT for nurse administration upon written direction of the physician. Written direction by the physician is provided as a courtesy to the resident/authorized agent and does not necessarily endorse or imply liability for use of the ADT. (This procedure would not apply to facilities that permit ADTs only for those who can self-administer medication.)

9. No physician order is issued because the ADT is not recommended by the physician and is not based on medical necessity. (Just as a banana need not be ordered simply because the resident likes it for dessert. This does not preclude a clinical entry acknowledging the use of the ADT by the resident. Regulatory authorities may ultimately decide the need for physician orders.)

10. ADT use is documented on the resident’s care plan.

11. The use of ADTs may be terminated at the facility’s discretion when a change in the resident’s status prohibits safe oral ingestion of the ADT (ie, the duty to protect the resident from harm).

Discussion continued on next page

Discussion

This article presents a guide to the formulation of policies and procedures to assist facilities in developing an approach to the use of ADTs (products) by LTC residents. This approach may alleviate the anxieties that may otherwise accrue to residents, families, and facility staff, should the subject matter become of concern after a resident has already been admitted. In so far as short-stay (subacute) patients are concerned, there is often too little time between application from the acute care environment and transfer to the facility to address this issue. However, acute care facilities are unlikely to be administering these substances, and if administered in the hospital, the criteria set forth here may have been met. Furthermore, subacute care patients and their families have the ability to resume ADTs following discharge.

The decision to incorporate one or another of these guidelines seeks to balance the rights of residents with the risks to residents (adverse reactions, drug interactions) and to the facility (vicarious liability), and burdens to the facility (facilitation of self-administration, actual administration, documentation, personnel time). As an analogy, a facility may perceive the balance of institutional risks and burdens of smoking or alcohol consumption with the resident’s legal right to engage in this activity in a fashion that arbitrarily does not allow these activities in the institution. On the other hand, some institutions may choose to allow these activities, but under certain circumstances and institutional safeguards.6,7

ADTs challenge LTC providers to seek a balance between resident welfare as perceived by the provider, as well as the cost of care, and the welfare and right of self-determination as perceived by the resident and family. This article aims to assist the facility in addressing this challenge. Note: Readers are welcome to copy and use the forms provided in this article.

The author reports no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Gomolin is Chief, Divisions of Geriatric Medicine and Clinical Pharmacology, Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, NY, and Clinical Professor of Medicine, School of Medicine, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY.

References

1. Scholz BA, Holmes HM, Marcus DM. Use of herbal medications in elderly patients. Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2008;16(12):24-28.

2. Associated Press. Herbal med use up despite little proof of safety. January 13, 2009. https://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/28640902. Accessed February 16, 2010.

3. What is complementary and alternative medicine? National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine Website. Accessed February 16, 2010.

4. Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database Website. https://www.naturaldatabase.com. Accessed February 16, 2010.

5. Jacobs BP, Gundling K. The ACP Evidence-Based Guide to Complementary & Alternative Medicine. American College of Physicians; 2009. Accessed February 16, 2010.

6. Lester PE, Kohen I. Smoking in the nursing home: A case report and literature review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2008;9:201-203.

7. Klein WC, Jess C. One last pleasure? Alcohol use among elderly people in nursing homes. Health Soc Work 2002;27(3):193-203.