Age-Related Eye Disease and Medication Safety

The leading cause of vision impairment and blindness in the United States is age-related eye disease, including age-related macular degeneration, cataract, diabetic retinopathy, and glaucoma. There are many medication safety issues associated with vision loss. Access to prescription information, including medication labels and usage instructions, is essential for the correct taking of medication. However, many people with vision loss are unable to access important instructions for use and safety information; determine the color, shape, and markings distinguishing a medication; or see markings on measuring or testing devices. Most older people who lose their vision due to age-related eye disease are not aware of services that can help them cope with vision loss, or techniques and devices that can make medication-taking and activities of daily living easier and safer. Clinicians can direct these patients to resources designed to help enhance patient function and medication safety. (Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2009;17[6]:17-22)

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Introduction

According to the 2006 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), of the more than 20 million Americans who reported vision loss, 6.2 million of them are age 65 years and older.1 In addition, there are approximately 9 million Americans age 45-64 who reported that they have trouble seeing, even with glasses or contacts, or that they are blind or unable to see at all.1 As the millions of baby boomers continue to age, the number of older persons with vision loss will continue to grow substantially.

The leading cause of vision impairment and blindness in the United States is age-related eye disease, including age-related macular degeneration (AMD), cataract, diabetic retinopathy, and glaucoma.2 The number of Americans with age-related eye disease and the vision impairment that results is expected to double within the next three decades.2 In addition to age-related eye diseases, physiologic changes in vision that occur with age—loss of near focus, reduced contrast sensitivity, and visual field impairment—contribute to vision impairment.

The Aging Eye

The most common age-related visual change is a decrease in the ability of the eyes to focus for close-up work (presbyopia). Other visual changes in the aging eye include a need for increased lighting, impaired color discrimination, and decreased contrast sensitivity (difficulty discerning an object against a similarly colored background). Most older adults need three to four times more light (particularly task lighting) than they previously did to perform certain types of everyday tasks. However, vision loss is not a normal part of aging.

When vision changes cannot be fully corrected to the normal range with ordinary eyeglasses, contact lenses, medication, or surgery, the result is permanently impaired vision, or low vision. Low vision refers to a range of vision capabilities and is common in older adults.

Ocular changes caused by aging are further compounded by eye disease. The four most prevalent eye conditions or diseases are diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, cataract, and AMD. Increased age is a risk factor for cataract, diabetic retinopathy, and macular degeneration. Persons with diabetes also have a greater incidence of cataract and glaucoma. Consequently, many older adults have multiple, overlapping eye conditions.

A complete review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of age-related eye disease is beyond the scope of this article.

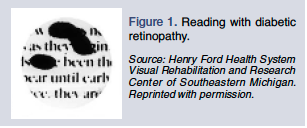

Diabetic Retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy occurs in 4.4 million Americans age 40 years and older,2 or approximately 25% of the 17.9 million Americans diagnosed with diabetes.3 It can be present even though no subjective signs of vision loss are experienced by the individual having the condition. Diabetic retinopathy can initially result in patchy vision loss and impaired visual acuity, but can advance to total blindness (Figure 1). Persons with diabetes may also have fluctuating vision, with vision appearing more blurry when blood glucose levels are too high or too low.

The combination of symptoms causes print to look hazy and spotty when reading. In addition, vision can be least dependable when needed most, when experiencing the effects of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. The vision changes associated with retinopathy can also result in difficulty locating an object in the supermarket aisle, measuring insulin, and participating in self-care activities such as shaving and makeup application.

The combination of symptoms causes print to look hazy and spotty when reading. In addition, vision can be least dependable when needed most, when experiencing the effects of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia. The vision changes associated with retinopathy can also result in difficulty locating an object in the supermarket aisle, measuring insulin, and participating in self-care activities such as shaving and makeup application.

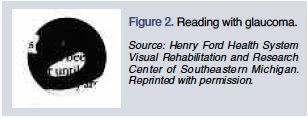

Glaucoma

Glaucoma affects more than 2.3 million Americans age 40 years and older, or about 1.9% of this population.2 Glaucoma prevalence is clearly related to age and race: it is more common in Blacks and Hispanics, and with increasing age; for those age 80 years and older, glaucoma affects more than 10% of Black men and Hispanic women.2

There are several forms of glaucoma. It is often referred to as the “thief of sight,” because one of the most common forms progresses in a slow and painless manner. Vision loss can be prevented if the glaucoma is treated in its early stages. Initial symptoms include decreased peripheral field of vision, difficulty in low light or nighttime conditions, and a subtle reduction in contrast sensitivity (Figure 2). Advanced glaucoma can ultimately cause total blindness. Reading print is difficult due to the limited number of letters or words that can fit into the reduced field of view. Because of its effect on peripheral vision, glaucoma can also affect activities such as avoiding objects when walking, locating a dropped object, and watching a sporting event.

There are several forms of glaucoma. It is often referred to as the “thief of sight,” because one of the most common forms progresses in a slow and painless manner. Vision loss can be prevented if the glaucoma is treated in its early stages. Initial symptoms include decreased peripheral field of vision, difficulty in low light or nighttime conditions, and a subtle reduction in contrast sensitivity (Figure 2). Advanced glaucoma can ultimately cause total blindness. Reading print is difficult due to the limited number of letters or words that can fit into the reduced field of view. Because of its effect on peripheral vision, glaucoma can also affect activities such as avoiding objects when walking, locating a dropped object, and watching a sporting event.

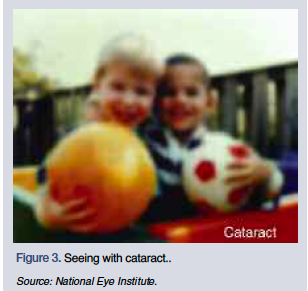

Cataract

A cataract is a clouding of the lens in the eye that affects vision. Cataract affects more than 22 million Americans age 40 years and older, or about one in every six people in this age range. By age 80, more than half of all Americans either have a cataract or have had cataract surgery.2

A cataract is a clouding of the lens in the eye that affects vision. Cataract affects more than 22 million Americans age 40 years and older, or about one in every six people in this age range. By age 80, more than half of all Americans either have a cataract or have had cataract surgery.2

Cataracts cause general blurriness, decreased contrast sensitivity, and difficulty with bright light and glare (Figure 3). Reading is difficult, as print appears faded and less sharp in detail. Other daily activities affected by cataract include locating a navy blue clothing item among other darkly-colored items, reading a glossy magazine page, and seeing the settings on a stove dial. Treatment for cataract is widely available and can eliminate vision loss due to the disease.

Age-Related Macular Degeneration

AMD is the leading cause of blindness in individuals older than age 65 years in the United States. More than 2 million Americans age 50 and older have late AMD.2

There are two forms of AMD: dry and wet. The most common symptom of dry AMD is blurred central vision that worsens slowly. Wet AMD can be severe and occur rapidly. A common symptom of wet AMD is that straight lines appear wavy, and central vision degrades quickly (Figure 4).

Macular degeneration is characterized by a central blind spot, resulting in distorted or absent vision in the central visual field. Other symptoms include impaired visual acuity, loss of detail vision, difficulty with daylight conditions, and need for increased lighting. Parts of letters and words may be distorted or missing when reading print. AMD blurs the sharp central vision needed for such straight-ahead activities as identifying faces, sewing, and driving.

Defining Vision Loss

Healthcare professionals should be familiar with the terminology associated with vision loss, as certain legal definitions and criteria are used to determine eligibility for government benefits or assistance, worker’s compensation, insurance disability benefits or other insurance coverage, special services, and driver’s licenses.

Healthcare professionals should be familiar with the terminology associated with vision loss, as certain legal definitions and criteria are used to determine eligibility for government benefits or assistance, worker’s compensation, insurance disability benefits or other insurance coverage, special services, and driver’s licenses.

Legal blindness is defined by law as visual acuity of 20/200 or less when wearing glasses or contact lenses or both, or if the field of vision for both eyes together is 20 degrees or less (tunnel vision).4 Confirmation of legal blindness is required for special consideration or disability services from the Internal Revenue Service, Social Security Administration, and other federal, state, and private organizations. The legal blindness criteria used to determine eligibility for government disability benefits do not necessarily indicate a person’s ability to function.

If persons cannot perform certain tasks because of their visual impairment, they are considered “visually disabled.” An exact rating or quantification of the disability is necessary to receive worker’s compensation, insurance disability benefits, legal claims, certain forms of government assistance, or assistance in educational settings. Visual disability is expressed in percentages to determine how much the whole person is disabled by his or her visual handicap. For example, total loss of vision in both eyes is a 100% disability of vision, but only an 85% disability of the whole person.5

Other vision terms are provided in the box on this page.6

Medication Safety Issues

There are many medication safety issues associated with vision loss. Access to prescription information, including medication labels and usage instructions, is essential for the correct taking of medication. However, many people with vision loss are unable to access important instructions for use and safety information; determine the color, shape, and markings distinguishing a medication; or see markings on measuring or testing devices. People with vision loss must rely on memory, use compensatory strategies or devices, or depend on someone else for help with their medications.

A 2002 study of 325 older persons (average age, 78 yr) reported that 39% were unable to read prescription labels, and 67% did not fully understand the information given to them; as a result, 45% were nonadherent with their medication regimen. These problems were especially prevalent in men and in people older than age 85 years.7 An earlier study found that 60% of older adults had difficulty reading their medication labels.8

Several studies have demonstrated the importance of label format—font type, point size, letter compression, line spacing—on readability, comprehensibility, and usefulness to consumers.9-12 One study noted significant improvements in comprehension and adherence among older adults when the prescription label was printed in 22-point Arial font,13 which is nearly three times the point size usually used on prescription labels. The findings of many of the studies suggest that older consumers may be unable to acquire information—such as product identification, instructions for use, and safety information—from prescription or product labels and various sources of consumer medication information (CMI). It is essential to ensure that the size of the print is large enough to enable information transmission from the label to the receiver.12

In a 2007 national poll conducted by the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB), 65% of those surveyed expressed concern about properly identifying medication.14 Further, a recent online survey conducted by AFB found that the inability to read medication labels and instructions has resulted in serious negative consequences for people with vision loss.15 The most commonly reported adverse outcomes due to inability to read drug labeling information are the following:

Taking the wrong medication

Taking an incorrect dosage of medication

Taking an expired medication

Inability to access the necessary information to refill medications on time Illness due to taking the wrong medication or incorrect dosage of medication

Emergency room visit or hospitalization

Additional expense

Increased anxiety

Inability to maintain confidentiality

Inability to detect pharmacy errors

Dependence on either trusted sighted companions or complete strangers to convey necessary drug information

These findings are of great concern, considering that most older people who lose their vision due to age-related eye disease are not aware of services that can help them cope with vision loss, or techniques and devices that can make medication-taking and performing activities of daily living (ADLs) easier and safer.16

Even though people of all ages with all degrees of vision loss are affected by the negative consequences of inaccessible medication information, there are currently no federal or state requirements for the format of information on prescription labels; and existing requirements for CMI provided by pharmacies are inadequate for persons with vision loss. Neither the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) nor the state boards of pharmacy have established any guidelines to assist pharmacies in making prescription labels accessible.

Guidelines for Prescription Labeling and Consumer Medication Information for Persons with Vision Loss

To promote medication safety and assist pharmacists in meeting the needs of their patients with vision loss, the American Society of Consultant Pharmacists Foundation and AFB developed Guidelines for Prescription Labeling and Consumer Medication Information for Persons with Vision Loss.17 In addition to specific format recommendations for prescription labeling and CMI, the guidelines also provide suggestions for making information accessible to people for whom larger print is not useful, recommendations for helping patients distinguish among prescription containers, and general information on assistive technology, resources, and services. The guidelines are available at https://www.ascpfoundation.org.

To promote medication safety and assist pharmacists in meeting the needs of their patients with vision loss, the American Society of Consultant Pharmacists Foundation and AFB developed Guidelines for Prescription Labeling and Consumer Medication Information for Persons with Vision Loss.17 In addition to specific format recommendations for prescription labeling and CMI, the guidelines also provide suggestions for making information accessible to people for whom larger print is not useful, recommendations for helping patients distinguish among prescription containers, and general information on assistive technology, resources, and services. The guidelines are available at https://www.ascpfoundation.org.

Medication Management Techniques and Tools

Persons with vision loss can use a variety of methods and tools to identify and distinguish between different medication containers; identify dosing frequency or dosing time of day; or track medication-taking. A combination of labeling methods—visual, tactile, visual/tactile, and audible—can be used with environmental modifications, such as organization of medications and use of adequate task lighting. Techniques may be as simple as placing a large-print, bold letter on the container or using an audible labeling system. A person with vision loss may require assistance in using these techniques and devices.

When determining the best method to distinguish between different medication containers, several factors should be taken into consideration.18 The most critical is the level of vision loss, including visual acuity, visual field, contrast sensitivity, and color discrimination. Additional patient-related factors are cognitive skills, hearing ability, manual strength, range of motion, fine motor coordination, tactile sensation, the number and type of medications and their storage and preparation requirements, the complexity of the patient’s medication regimen, and the availability and level of caregiver support. The availability and cost of labeling materials or devices and ease of use also should be considered.

Services and Resources for Information on Low Vision

Too often, people with low vision think that nothing more can be done to help them see better, so it is particularly important that they know what kind of help is available. Many clinicians are unaware of services that can help their patients cope with vision loss and reduce the disability associated with the condition.

Vision rehabilitation services can make the difference between living independently and losing independence. Vision rehabilitation is the umbrella term for the specialized training and counseling services that help people with vision loss develop the skills and strategies needed to accomplish their goals in all stages of life. While vision rehabilitation cannot restore normal vision, it can help people maximize their existing vision and equip them with devices and techniques to maintain an independent lifestyle. The purpose of vision rehabilitation is to overcome visual disability with vision-enhancing devices, adaptive technology, adaptive skills, and environmental modifications.19 Older adults who are well informed are more likely to seek out vision rehabilitation services when vision changes begin to affect their ability to perform day-to-day activities.

Information about medication management techniques, services available for those living with vision loss and how to locate them, environmental modifications to make living with vision loss easier, and specialty products is available on the AFB Senior Site® (www.afb.org/seniorsite).

Summary

Age-related eye diseases and physiologic changes in vision that occur with age, such as loss of near focus, reduced contrast sensitivity, and visual field impairment, contribute to a reduction in visual acuity, which can lead to medication safety problems. The inability to read medication labels and instructions has resulted in serious negative consequences for people with vision loss.

As the millions of baby boomers with vision loss continue to age, the numbers with vision loss will continue to grow substantially. In spite of this fact, there are currently no federal or state requirements for the format of information on prescription labels, and existing requirements for CMI provided by pharmacies are inadequate for persons with vision loss. Neither the FDA nor the state boards of pharmacy have established any guidelines to assist pharmacies in making prescription labels accessible.

The Guidelines for Prescription Labeling and Consumer Medication Information for Persons with Vision Loss provides specific format recommendations for prescription labeling and CMI, suggestions for making information accessible to people for whom larger print is not useful, recommendations for helping patients distinguish between different prescription containers, and general information on assistive technology, resources, and services.

Most older people who lose their vision due to age-related eye disease are not aware of services that can help them cope with vision loss, or with techniques and devices that can make medication-taking and performing ADL easier and safer. Clinicians can direct patients with low vision from any cause to resources designed to help enhance patient function and medication safety.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Dr. Feinberg is Research Director, American Society of Consultant Pharmacists Foundation, Alexandria, VA; Dr. Rogers is Senior Site Program Manager, American Foundation for the Blind Center on Vision Loss, Dallas, TX; and Ms. Sokol-McKay is a private practitioner and consultant in Low Vision Rehabilitation and Adaptive Diabetes Self-Management, Bethlehem, PA.