A Day in the Twilight of Life

“I’m tired. I don’t know what’s the matter with me.”

As usual, Grandma expected to be well. It was a weakness not to; she expected it even at 94, and when it eluded her, there was a taint of disgust in her voice.

I leaned over to speak into her ear. “I’ve come to see you, Grandma. It’s Kitty.”

“Kitty, why how wonderful. I haven’t seen you for such a long time.” Her voice was weak. She didn’t move, other than her shoulders laboring to aid her breathing. She continued to face the wall in her room in the nursing home, her knees pulled up to her frail body.

Enough had passed between us for me to be reassured that she knew who I was. It was just before 10:00 AM, and I had hoped her mind might be clearest early in the day. Reports were such that often she didn't recognize someone. And the memory of who had been there or called of late did not last. I thought it was likely that this would be the last time I would see her. It encouraged my heart that she could enjoy the fact that I’d come...even if it was only a momentary happiness.

She was alert and conversing more easily when her son Jake called. She launched into a rerun of a conversation that took its usual path, saying she was not good, not good at all, but better than yesterday, and how was the family? She smiled into the phone, almost laughing when he spoke of his first grandson, her newest great-grandchild. It was amazing how the energy rose in her body. Still, she kept the same position, right hand cradling her cheek, left hand holding the receiver to her ear. There was no earring. This was the first time I’d ever seen her without jewelry. She lifted the phone from her ear, her hand more slender than I remembered, but as always, her nails immaculately painted, thanks to the caring staff. I set the phone back in the cradle and drew nearer to her, my knees on the bed, leaning close to her, speaking by her ear to ease our conversation.

“How is the house?” She wanted to know how the home she had lived in so many years was being kept up.

“It’s beautiful.” I paused and she was silent. “Grandma, you are well taken care of here.”

“Yes, they are so good to me.” She paused, frowning. “The kids shouldn’t have brought me here so soon.”

“You always said your wish would be that you could die in your own bed.”

The energy returned to her voice. “Well, I ain’t dead yet.” Her lips formed a wry smile, and we both laughed.

The nurse was warm to me as I walked out to the nurse’s station. “I saw you on the bed with her, so I didn’t come in.”

“Oh, great,” I groaned. Inside I felt self-conscious about how that may have looked.

She laughed, “No, it was really sweet. Your grandmother is my favorite person in this place.” She meant it, and I understood why. There really is no one like my grandmother for spunk.

“She has the funniest remarks with her special way of saying them, and will walk past the nurses station and just be so appreciative for anything you do for her. She makes you feel so special.”

The other nurse laughed. “She’s one of a kind. She scares me though, when she heads down the back stairs.”

“Three years ago,” I told them, “when she couldn’t lower her new ironing board, she took it down stairs far narrower and steeper than those.” They believed me. “She’s like a mountain goat.” They laughed, having experienced her remarkable agility all too well.

The nurse went on. “She’s been particular up till now. So neat. Wanting her hair in place, her clothes just so.”

We talked about the fact that she was no longer eating much, and that she was down to 95 pounds, at least 60 pounds less than midlife. The nurse then mentioned that an appointment was scheduled to have the nodule that had grown on her thyroid gland checked.

“If something is wrong, do they plan to do anything about it?” I asked.

The nurse indicated that she was thinking the same thing and shook her head. “Perhaps you could let Uncle Jake know about this. It seems to be that perhaps things are a bit overdone.” We were both on the same wavelength, and she planned to call him. Lunch was to be served at 11:50, and I said I would be back.

* * *

The shades were drawn to the side, and the sunshine shone on her face. She had turned to face the light, legs still drawn up, and she wore a serene smile even as her eyes were closed and her face tipped towards the unusually bright February sunshine.

“Would you like to have lunch?”I asked. Her eyes opened.

“Yes, yes I would.” She smiled.

“Do you know who I am?”

“You are Kitty. I had to guess. Is that right?” She smiled, pleased with herself when I gave my assent. My heart leapt over the fact that she had remembered.

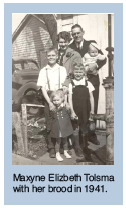

“Jeanette just called. She said she didn’t know that you were coming so soon.” The two youngest of her devoted brood were still living and called often. Of late, Grandma was not reaching the phone to answer it when it rang, and it was much more difficult to get through to her.

The nurse came in to take her to lunch and turned off her oxygen. Grandma took her arm and I put mine where she could grab hold of it as she moved to the wheelchair. I found some glasses on the night table and noted that they weren't bifocals. She had just been to the eye doctor and gotten new ones that were supposed to have bifocal lenses, so I asked the nurse about it and wheeled her to the dining room.

Her breathing was more labored. Fried chicken, mashed potatoes, and gravy, cauliflower ground with cheese and spice cake made for a nice meal. She reached for her glass of orange juice, and I quickly removed the plastic wrap. I undid the napkin, and she laid the silverware out on it. Her hands danced a bit on the silver, unsure which utensil to choose. She picked up the fork and missed the potatoes. Stabbing around, she missed the plate.

“I can’t see a thing.” I took her glasses off and cleaned them. She didn’t have the energy to eat, or speak much. I asked the aide to bring her oxygen. After it was back on, she perked up, and made another stab at the food. I encouraged her to pick up the chicken with her fingers. Twice she picked up the chicken by the larger drumstick end and bit the cartilage on the other end. She picked up the spoon and daintily removed the cartilage from her mouth. I’d hoped for protein to make it in.

“Turn it around, Grandma.” She did and took one bite of chicken, and she was done. Two bites of potatoes. She picked up the knife, but then set it back down. Too many options. She sat back and sighed.

“How’s it going with the boss?” she queried. “You have to work for it.”

I was stunned by her phrasing. Brilliance has little to do with what makes the majority of us truly successful in life. Early on I understood that I needed to “work for it.” Grandma drove that point home. She had completed the 8th grade and then helped work to support the family. She had raised five siblings and carried a baby on her hip beginning at age four. She had modeled a strong work ethic.

I was stunned by her phrasing. Brilliance has little to do with what makes the majority of us truly successful in life. Early on I understood that I needed to “work for it.” Grandma drove that point home. She had completed the 8th grade and then helped work to support the family. She had raised five siblings and carried a baby on her hip beginning at age four. She had modeled a strong work ethic.

She made another go at her food with her fork, but nothing came up on it.

“Would you like another bite of potatoes? I held out the spoon. She ate it and said it was enough. We chatted, and I offered a bite of spice cake. She took it followed by another sip of beverage, this time water, thickened to aid swallowing. She was finished.

“I have to go to the bathroom.” She stood up abruptly and left the wheelchair behind. I quickly turned off the oxygen and threaded the cord so she wouldn’t trip, and dragged the machine along as she took off at a clip.

Her shoe was untied, so I asked if I could tie it. “Is this my room?” she asked as we came to a halt.

“Not yet, Grandma.” We made it down the long hall and turned the corner. She was losing steam.

“Is this my room?”

“Almost there, Grandma.” Bed was a welcome place. She was tired and needed to rest. The glasses with the bifocals were now at her bedside stand, and the nutritional beverage that had spilled in the paper cup with the narrow base was gone.

Deciding to come back later, I slipped out the back entrance and thought about how close this was to her home she’d lived in for more than 40 years. I savored walking the streets and the many conversations we’d shared, arm in arm, underneath the canopy of elms.

* * *

“Hello, Grandma.” I had given her a few hours to rest and I was back.

“What,” she said flatly. She looked at me strangely. “I don’t want any.” She curled back into the fetal position.

“Have you had any visitors today?”

“No.”

“Has anyone called?”

“No.”

“Grandma, it’s Kitty.”

She paused. “Oh. Well.” She lay her head back down. I would be leaving the next day, and I knew in my heart now, this would be the last time I would see her.

“I want to rest a little while before I go home.”

“Okay, Grandma. You rest a bit.” Deciding I didn’t care what anyone might think, I took off my shoes and climbed up on the bed and lay down beside her. From here, I could speak into her ear, and gently massage her shoulders and back. I ran my hand over her hip that was now all bone.

Already knowing the answer full well, I asked, “Grandma, do you still have all your own teeth?”

“Every one.” As I tried to watch her face from behind, all I could see was the profile I knew so well. She set her teeth together the way she did when she was pleased, and her cheek rose and wrinkled a bit more. She was proud about having all of her teeth. What else would she remember? I reminded her of the goat that climbed up on the guest’s car out on the acreage.

“That goat did so many things,” she added. I traced through the old stories, to tap into the favorite neuronal pathways, searching for memory. “Remember Old Bess? Remember how she kicked the teacup up into the air?”

“Yes, it went way up in the air.”

“And there was Hank, with the long arms, holding the handle.” She laughed.

“Grandma, you taught me how to roast a chicken and how to bake bread. Remember how we sat on the back porch?”

“Yes, Eddie sure liked that back porch.” I didn’t say anything. It was built long after he was gone. Maybe she was talking about the acreage? It did not have a back porch, either. She was confabulating.

“Grandpa sure loved you.”

“Yes, and I loved him.” We talked of her love for her family. One by one, we talked about how they loved her, and she spoke of how she loved them.

“I go by two names. Katherine and Kitty. Which name do you like best?”

There was a pause, and she said softly, “Katherine. I love you, Katherine. When I breathe.” She struggled for the next breath. “With every breath in me.”

She remembered my birth. “I was right there, boy,” she was still adamant about the privilege of seeing my delivery. The memory was etched.

“Remember the time I got into the henhouse?”

Her cheek wrinkled up towards me again, and I detected that a smile had again crossed her face. “Nothing like an old hen sitting on her eggs. I’m a hen.”

“You were a wonderful mother, Grandma.” We talked about how she had felt when she held my father, her first baby.

“He was such a beautiful baby.” She was surprised to know I was the same age she was when she had become a grandmother.

“What does that make me? Old! I’m insulted.” Her shoulders shook a bit with laughter. She liked a good joke, especially if it were her own.

A half a dozen times when the conversation died, and I didn’t know what to say next, I would tell her I loved her, sometimes giving her a nibble on her ear, the way Grandpa had done. Her cheek would crinkle and I knew she was smiling with enjoyment. Tears started to flow. They were mine.

“You always loved Jesus, Grandma.”

“Yes, I did. I still do.”

“He will come for you soon. His arms will be there to hold you and take you to heaven.”

“That will be nice.”

What could I talk about that we had discussed so many times? Something that would jog her memory?

“I remember how you liked to put onion in your salad.”

“Oh yes, got to have onion. I like onion. I love onion. Onion in a cup.”

“Remember the onion container? The one you kept in the frig.” Her cheek wrinkled again, betraying a smile had again come to her face.

“Yes, she said delighted with the memory. Onion in a cup. I always liked it. I am going home now. I don’t remember the way. I’m tired.”

The tears flowed hot down my cheek. She nestled backwards into my hand as I stroked her back.

“Ummmm. That feels good.”

I got up after some time had quietly passed, and she did not notice. Looking at her face with respect, awe, sadness, I desired to say one more thing. I thought about the last words I would to say to her. I had already said them.

Quietly, I picked up my coat, choosing not to say goodbye. It was seven minutes to four. I let my eyes cherish what I held as last moments of this tender memory, allowing her fragile form to seal into my mind. I was at peace. I would see her in eternity. There I would again be able to say hello to her mind.

The author’s grandmother’s cognitive decline and medication mismanagement, which resulted in the nursing home placement, have been the inspiration for the author’s research on medication management assessment. Dr. Anderson is at Harding University, College of Pharmacy, Searcy, AR, and with Pharmacists International Consulting Specialists, Pullman, WA.