When Do Poor Outcomes Constitute Poor Care? Making the Case for Unpreventable Outcomes in Long-Term Care Residents

Affiliations: 1Director, Clinical Affairs and Industry Relations, AMDA – The Society for Post Acute and Long-Term Care, Columbia, MD 2School of Nursing, Louisiana State University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA 3Section of Geriatric Medicine, Department of Medicine, Louisiana State University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA

Abstract: Pressure ulcers, falls, altered nutritional status, and dehydration represent common clinical syndromes affecting the geriatric population who reside in long-term care settings. Appropriate assessment of these syndromes involves knowledge, an interdisciplinary approach to care, appropriate care plan development and implementation with updates, and proper documentation and communication with the resident and family. When poor outcomes occur, the initial reaction by residents, their families or other caregivers, or legal counsel is to assume that the event was a result of a poor level of care. However, poor care in the nursing home should be distinguished from unpreventable outcomes. This article explores the difference between these two important distinctions.

Key words: Unavoidable outcomes, unpreventable outcomes, pressure ulcers, falls, malnutrition, dehydration.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Pressure ulcers, falls, malnutrition, and dehydration are common syndromes in the frail, elderly nursing home population, and they deserve special attention relative to the training of nursing home staff, as well as the investment of extra time in a typical patient care visit. When poor outcomes occur, such as worsening pressure ulcers, altered nutritional status or unintended weight loss, a fall with injury (ie, fracture), or dehydration, the initial reaction by a resident, family members or other caregivers, or legal counsel is to assume that the event was a result of a poor level of care. However sweeping such assumptions, they are challenging to dispute without the support of well-documented steps toward prevention, management, and follow-up, as well as a record of ongoing communication with residents and families. There are, in fact, many instances in which these syndromes are not preventable. In order to determine whether an outcome is unavoidable depends upon adherence to a series of steps, often to be repeated throughout the course of an individual’s stay in the facility, upon readmission after a hospitalization, and in response to any change in the resident’s clinical status. The process always begins with the identification of risk factors for the syndrome, and assessment of the resident’s level of risk. From there, appropriate measures, including a tailored care plan, is necessary to address the individual’s specific circumstances and risk for an event. This care plan must be reviewed and updated regularly with ample documentation of any changes. This article explores circumstances in which negative outcomes are not avoidable, specifically with regard to pressure ulcers, falls, weight loss/malnutrition, and dehydration. A supplementary tip sheet offers an overview of the multidisciplinary approach to care in these four domains and provides guidance on the measures that providers should take to document the presence of certain resident factors that support an unpreventable outcome.

Pressure Ulcers

A pressure ulcer is a localized injury to the skin or underlying tissue that results from pressure combined with shear or friction, usually over a bony prominence (eg, hips, trochanter, buttocks, sacrum, heels).1 Pressure ulcers should be distinguished from other types of ulcers (eg, ischemic, venous); frequently residents of long-term care facilities are misdiagnosed with pressure ulcers when in fact the ulcer may be ischemic (eg, red and white, located on anterior legs, tips of toes, heels, lateral and medical feet) or venous (eg, dark blue, thickening of skin, located on lower legs and ankles). Patients who are bed bound or require extensive assistance with bed mobility are at high risk for pressure ulcers. A skin risk assessment tool (eg, Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk, Norton Scale) should be used to determine whether and to what degree the patient is at risk for a pressure ulcer.2,3 What should follow is an interdisciplinary care plan for the resident that addresses either the high risk for altered skin integrity or the existing pressure ulcer, if already present, and that outlines specific interventions to address prevention and treatment. Appropriate interventions that are part of a multidisciplinary care plan are listed in the supplementary tip sheet.1 When an ulcer is present, it is beneficial to use an appropriate monitoring tool such as the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing or other tool.4 However, accurate supervision of the wound (eg, dimension, wound bed, drainage, surrounding skin) on a weekly basis by a registered nurse is essential.

Relative to support surfaces, patients at risk for skin breakdown should be placed on a static (nonpowered) pressure redistribution surface such as an overlay, foam mattress, or seat cushion rather than a standard mattress. For a patient who cannot vary position easily without placing too much weight on the pressure ulcer, use of a dynamic (powered) low–air-loss or alternating pressure mattress can be helpful. This is also useful in cases of recalcitrant pressure ulcers for which treatable factors that might be delaying healing cannot be readily identified.5

When a significant change has occurred to the wound site, such as increased size or amount of drainage, change in the character of the drainage, or erythema, the care plan should be updated to reflect a new treatment plan. Risk factors for new pressure ulcer development or the nonhealing of an existing pressure ulcer should also be reevaluated, and reassessment would be handled in the same fashion. According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) guideline F-tag 314, such factors include: (1) comorbid conditions (eg, diabetes mellitus, end-stage renal disease, thyroid disease, immunodeficiency state); (2) drugs that may affect ulcer healing (eg, steroids); (3) exposure of skin to urinary or fecal incontinence, or history of a healed stage III or IV pressure ulcer at the same site; (4) impaired diffuse or localized blood flow (ie, general arteriosclerosis, lower-extremity arterial insufficiency); (5) impaired or decreased mobility and functional ability; (6) increase in friction or shear at the site; (7) moderate to severe cognitive impairment; (8) resident refusal of some aspects of care and treatment; and (9) undernutrition, malnutrition, and hydration deficits.6

Assuming the interdisciplinary care plan has been updated regularly, having allowed a reasonable period of time for healing (generally 6-8 weeks with each update), and with proper documentation of interventions, the wound may meet the definition of unavoidable if identifiable risk factors for unavoidability can be determined and documented. According to the same CMS guideline, an unavoidable pressure ulcer is one that develops even though a facility has done all of the following: (1) evaluated the patient’s clinical condition and risk factors; (2) defined and implemented interventions consistent with patient needs, goals, and recognized standards of practice; (3) monitored and evaluated the impact of these interventions; and (4) revised the approaches as appropriate.7 In addition to those conditions outlined in the CMS guideline, several other comorbidities or clinical states can increase the resident’s risk for an unavoidable pressure ulcer, including cachexia; metastatic cancer; multiple organ failure; sarcopenia; severe vascular compromise; and terminal illness.1 Documentation of these risk factors is critical.

Falls

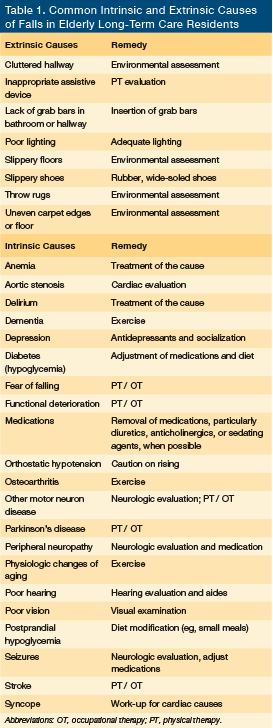

The accepted definition of a fall in an older person is the inability to maintain an appropriate lying, sitting, or standing position, resulting in sudden, unintentional relocation to the ground or contact with another object below the individual’s starting point.7 The percentage of long-term residents experiencing one or more falls with major injury is a CMS quality measure for nursing homes.8 Common risk factors for falls are either intrinsic or environmental/extrinsic, and they are listed in Table 1 along with suggested remedies for either type.9 Residents on admission/readmission should be assessed for fall risk using a valid and reliable fall risk quantitative scale. If the resident is determined to be at high risk for falls, a multifactorial and multidisciplinary care plan should be developed that identifies risk factors and implements appropriate risk interventions intended to prevent falls or fall-related injuries. Some risk factors may be modifiable whereas others may not. For instance, many times falls in frail older residents with multiple comorbid illnesses might not be preventable. Therefore, a realistic care plan might involve attempts to diminish the frequency or consequences of falls, rather than attempt to eliminate them.

The tip sheet lists appropriate multidisciplinary care plan interventions for falls.10,11 A bed and/or chair alarm may be useful for the long-term care resident with cognitive impairment who has experienced one or more falls in order to alert staff of their movement and remind the patient to seek assistance. However, their use is not evidence-based, and their efficacy is dependent upon variable factors, such as the timeliness of the staff’s response to the alarm.12 Bed and chair alarms also may be subject to malfunction, might become disengaged by the resident, or might frighten the resident, possibly leading to injury.7 Hip protectors can be useful for the prevention of injury in residents with recurrent falls.13 Wedge cushions can be provided by a physical therapist and are helpful when positioning a nonambulatory resident to prevent him or her from sliding out of the chair.7

The fall risk care plan should be tailored to the specific characteristics of the individual. For instance, a low bed and floor mat to prevent injury from falls out of bed may not be useful in a highly mobile resident with proximal muscle weakness, who frequently attempts to get out of bed from a low center of gravity, and who may be at risk for tripping over the mat. Formal physical or occupational therapy evaluation may provide little benefit if the resident is unable to follow commands. In such cases, restorative nursing in the form of regular exercise to maintain function may be the most logical intervention.14 Use of assistive devices requires evaluation by physical and occupational therapists, especially if the resident has significant cognitive dysfunction and poor safety awareness, since incorrect use may result in serious injury from trips and falls. Staff may be tempted to use other last-resort interventions for the frequent faller, such as a scoop mattress to prevent rolling out of bed, or a self-releasing lap belt or lap trap. These are considered to be restraints and should be avoided. After a fall, the care plan should be updated to take into account the specific circumstances of the event.

Documentation of the circumstances of a fall (when known) at the time of the incident is essential, with reporting to the practitioner and continuous monitoring for delayed injury from the fall. Assuming that a resident has been care planned accordingly for falls with appropriate updates and additional interventions implemented as necessary, and with appropriate documentation, the occurrence of a fall with or without serious injury may be determined to be unpreventable.

Weight Loss/Malnutrition

One CMS-recognized quality measure for long-stay residents of nursing homes (ie, residents whose cumulative days in the facility are at least 101 days) is the percentage of residents who have lost too much weight.8 Malnutrition may be present in 2% to 38% of nursing home residents and malnutrition risk may be present in 37% to 62% of residents.15 The Minimum Data Set collected on nursing home residents at admission and at regular intervals indicates that an intake of less than 75% of food provided should trigger a nutritional assessment.16

Malnutrition is associated with longer hospital stays and greater likelihood of rehospitalization, higher cost of hospitalization, and diminished survival, compared with well-nourished patients.17 Lim and associates17 found malnutrition to be a significant predictor of mortality (adjusted hazard ratio, 4.4; 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.3–6.0; P<.001), with mortality in malnourished versus well-nourished patients higher at 1 year (34% vs 4.1%), 2 years (42.6% vs 6.7%), and 3 years (48.5% vs 9.9%, respectively; P<.001).

Frail nursing home residents may be at risk for altered nutritional status and unintended weight loss due to comorbidities, such as AIDS, advanced dementia, cancer, chronic infections, inflammatory conditions (eg, pressure ulcers, chronic obstructive lung disease), depression, uncontrolled diabetes, hyperthyroidism, malabsorption syndromes, oral disease, Parkinson’s, polypharmacy, swallowing disorders, and therapeutic diets.18-20

Assessment of body mass index (BMI) should be performed regularly to monitor residents for high risk of malnutrition, and should be accompanied by appropriate interventions. A BMI of less than 18.5 kg/m2 indicates high nutritional risk. In addition, low serum albumin is used often in the nursing home setting as a risk indicator for morbidity and mortality. It lacks sensitivity and specificity as a nutritional risk indicator, likely representing instead a marker for injury, disease, or inflammation. A serum albumin level will generally reflect a 6- to 8-week average, whereas the prealbumin level has a shorter half-life of 24 to 28 hours and can yield a more immediate indication of nutritional status, though it has many of the same limitations as the serum albumin level.15

Residents at high risk for malnutrition should be identified on admission through a mini or other nutritional risk assessment that is validated and reliable and that indicates the level of risk (ie, low, medium, or high). High-risk residents should be care planned using a multidisciplinary approach, with regular updates and interventions in the presence of continuing weight loss, or upon readmission from the hospital.16

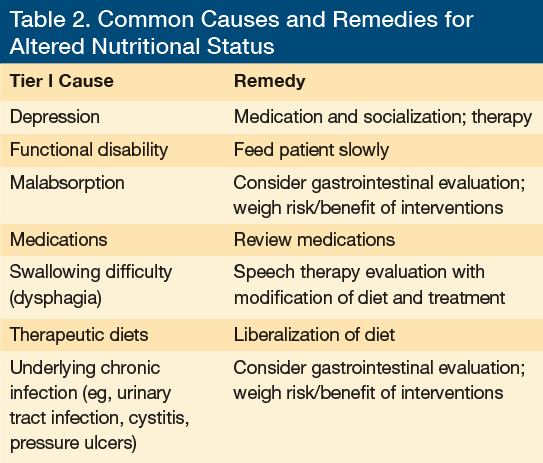

Depending on the particular individual and any present comorbid conditions, a tier I assessment should be performed to evaluate for common, treatable, or potentially reversible causes of altered nutritional status (Table 2). It should be followed by a patient-specific multidisciplinary care plan with specific interventions to address the issue/s identified (see tip sheet).18,21,22 This plan should be updated at 3-month intervals or more frequently, as well as after hospital readmission, depending on the success of the interventions.18,23

If the interventions outlined in the initial care plan or updates do not lead to improved weight, laboratory parameters, and cognitive and functional status, a tier II assessment may be in order at the discretion of the healthcare provider and multidisciplinary team. A tier II assessment should be used to identify other, more rare causes of weight loss for which treatment is not likely to reverse the process and for which further investigation may cause harm to the resident or is not in the resident’s best interest. Tier II–identified causes of weight loss might include cancer, progressive or terminal dementia, other degenerative neurologic conditions, and end-stage cardiac, hepatic, pulmonary, and renal illnesses.18 Appropriate intervention, based upon the tier II assessment, should be consistent with the individual’s expectations and wishes, and those of the family. Most important is a properly documented discussion with the family weighing the benefit and risk of further interventions; this is particularly relevance in making decisions regarding end-of-life care, such as using a feeding tube or pursuing potentially unnecessary, aggressive interventions in a resident with end-stage disease or terminal illness.18,24

Failure to prevent worsening nutritional status and weight loss despite sufficient care planning and updates spanning several months may be an indication that the weight loss is not preventable—but this conclusion should only be reached after a thorough search for treatable causes has been performed.18 When altered nutritional status is not preventable and weight loss occurs, more than likely a chronic inflammatory state, malignancy, or other inflammatory process is present (eg, cytokine-induced cachexia, malabsorption syndromes), resulting in depletion of nutritional stores.18,25

Dehydration

Long-term care facilities are reluctant to have practitioners make the diagnosis of dehydration because it is considered to be a sentinel event by CMS and implies a poor level of care or neglect.26,27 In fact, dehydration is an unreliable indicator of quality of care. Signs and symptoms of dehydration in nursing home residents (eg, dry mucous membranes, sunken eyes, dry axilla, capillary refill time, poor skin turgor, dark urine28) may not be specific or sensitive, and can therefore be misleading. Clinician reliance upon presentation of symptoms as opposed to laboratory values frequently results in misdiagnosis of dehydration in the nursing home setting. In addition, practitioners often use the term dehydration interchangeably with the term intravascular volume depletion.29 Complicating the issue is that there is no universally accepted definition of dehydration,28 and that nursing home residents may have a serum osmolality in the high-normal range without overt clinical evidence of dehydration, and an accompanying elevated sodium, or blood urea nitrogen/creatinine (BUN/Cr) ratio, indicating a different central osmolality setting.30

Dehydration refers to loss of total body water, producing hypertonicity, which now is the preferred term in lieu of dehydration; whereas volume depletion refers to a deficit in extracellular fluid volume. In particular, hypertonicity implies intracellular volume contraction, whereas volume depletion implies blood volume contraction.31 Hypertonic dehydration results in a loss of total body water, with or without salt, at a faster rate than the body can replace it. Said in another way, hypertonic dehydration implies intracellular water deficits stemming from hypertonicity and a disturbance in water metabolism. In contrast, volume depletion (extracellular fluid volume depletion) refers to a net loss of total body sodium and a reduction in intravascular volume. Both require evaluation of laboratory values to make the diagnosis.31 The diagnosis of dehydration is confirmed when the serum osmolality is greater than 295 mOsm/kg, while intravascular volume depletion is diagnosed when the ratio of BUN/Cr ratio is >20-to-1, or the serum sodium is >145 mg/dL, with osmolarity = 2 (Na+) + glucose/18 + urea/2.8.29,32

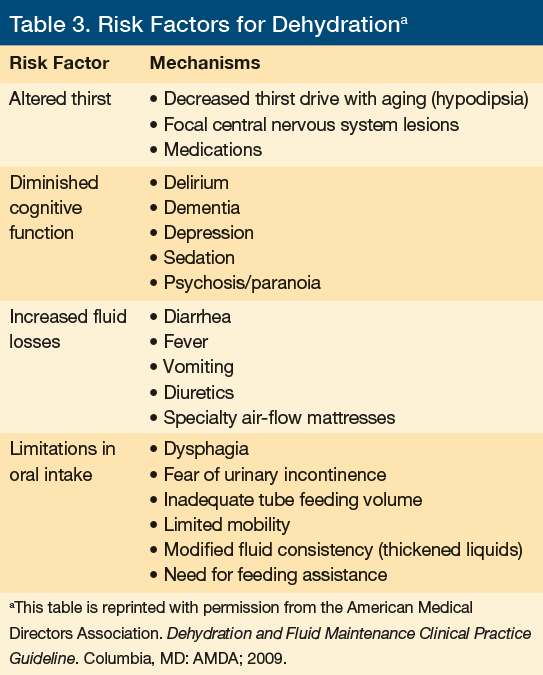

On admission, residents determined to be at risk for dehydration should have a multidisciplinary care plan developed (see tip sheet). Risk factors for dehydration are provided in Table 3. It is also important to know the medications that can increase the risk of dehydration28; angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers can prevent activation of pathway for compensatory sodium retention; caffeine, laxatives, lithium, diuretics, and theophylline preparations affect diuresis; tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors can cause hyponatremia and inappropriate antiduiretic hormone secretion (ie, SIADH); and products with vitamin D and calcium can cause hypercalcemia. Additionally, lack of familial support and insufficient staffing at the facility can also precipitate episodes of dehydration in the long-term care resident.33

The decision to treat dehydration in this setting depends on whether the resident is hemodynamically stable as well as on the severity of the dehydration. The wishes of the resident and/or family should be taken into consideration, with documented communication of the risks and benefits. Mild dehydration may be treated with an aggressive oral hydration protocol using fluid alternatives such as juices, broths, and flavored electrolyte solutions. Moderate dehydration in a hemodynamically stable individual can be treated with intravenous fluid or hypodermoclysis infusion.34 Severe dehydration associated with vascular compromise (hypotension and reduced urine output) should be treated with hospitalization.28 Attempts to treat dehydration in some residents may be inappropriate for ethical reasons (eg, in severe end-stage dementia, or when treatment with palliative measures only has been dictated by the family/legal guardian or by an advance directive).28

Measures for preventing dehydration in the nursing home setting involve the provision of fluids via oral, intravenous, or hypodermoclysis, sufficient to replace measurable losses with the recommended minimum total fluid intake being 1500 to 2000 mL/day. Fluid requirements can also be calculated by the following formula: 100 mL fluid/ kg of body weight for the first 10 kg of body weight; 50 mL fluid/kg for the next 10 kg of body weight, then 15 mL fluid/kg for each kg after 20 kg of body weight.28,34

In certain instances, prevention of dehydration may not be possible.28 Examples include dysphagia (where it may be impossible to give enough fluids due to the need to give only thickened liquids), chronic illness (eg, where provision of the recommended amount of fluid might precipitate recurrent congestive heart failure or worsening chronic renal failure), or in cases of cirrhosis. In addition, the need to treat hypertension or congestive heart failure with diuretics can also lead to dehydration.26 Lastly, dehydration may be difficult to prevent in a frail elderly resident without access to high-tech monitoring of fluid volume that is normally possible only in the hospital setting (ie, central line monitoring in the intensive care unit).

Frail elderly nursing home residents with multiple comorbid illnesses or terminal states (eg, severe dementia) who develop significant dehydration (ie, moderate to severe) despite appropriate monitoring and interventions with ongoing care plan revision may have dehydration that is unpreventable.35 Disease processes that cause fluid or electrolyte disturbances, or affect fluid intake by impairing consciousness (eg, delirium, urosepsis, pneumonia, or other acute illness), or physical condition (eg, illness that makes it too painful to drink) can undermine attempts to provide adequate hydration in at-risk residents. In such cases, dehydration might be viewed as a consequence of the dying process, rather than as a preventable condition that has resulted from poor care.27 In all cases, proper documentation of preventive interventions and communication with the resident and/or family are essential.27

In end-of-life situations, discussion with the resident/family (with appropriate documentation) about the option of not providing hydration therapy may be provide other palliative benefits for the resident.35 For example, purposeful dehydration helps diminish pulmonary secretions, which in turns reduces cough, congestion, and the need for suctioning, and decreases the production of gastrointestinal fluid, which in turns may reduce nausea, bloating, and regurgitation of gastric contents.

A full discussion of the benefits of purposeful dehydration during end-of-life palliation is beyond the scope of this review.

Conclusion

Pressure ulcers, falls, altered nutritional status and weight loss, and dehydration are challenging geriatric syndromes that deserve special attention in the nursing home setting. This involves the development of comprehensive and multidisciplinary care plans to identify risk factors, define, and implement appropriate interventions, update the plan when appropriate, communicate with the resident and/or family, and properly document all steps and communication. Inability to prevent these syndromes can only be determined after the above process has been exhausted.

Finally, it is important to note that an unavoidable pressure ulcer, altered nutritional status, dehydration, or a combination that is determined to be unpreventable may be a sign of failure to thrive. In such cases, and in taking into account specific characteristics of the patient, consideration should be given to changing the plan of care to a palliative approach or even to the consideration of hospice, in which unavoidable or unpreventable conditions are an expected outcome. Such a decision should come only after ample discussion and agreement with the patient and his or her caregivers.

References

1. AMDA. Pressure Ulcers In the Long-Term Care Setting: Clinical Practice Guideline. Columbia, MD: AMDA; 2012.

2. Kring DL. Reliability and validity of the Braden scale for predicting pressure ulcer risk. J Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurs. 2007;34(4):399-406.

3. Norton D. Calculating the risk: Reflections on the Norton scale.1989. Adv Wound Care. 1996;9(6):38-43.

4. Thomas DR, Rodeheaver GT, Bartolucci AA, et al. Pressure ulcer scale for healing: derivation and validation of the PUSH tool. The PUSH Task Force. Adv Wound Care. 1997;10(5):96-101.

5. Mclnnes E, Jammali-Blasi A, Bell-Syer SE, Dumville JC, Cullum N. Support surfaces for pressure ulcer prevention. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;13(4):CD001735.

6. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS Manual System, Pub.100- 07 State Operations, Provider Certification. Department Health and Human Services. Published November 12, 2004.

7. AMDA. Falls and Fall Risk: Clinical Practice Guideline. Columbia, MD: AMDA; 2011.

8. Nursing Home Quality Initiative: Quality Measures. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Updated March 28, 2014. Accessed September 4, 2014.

9. Levencron S, Kimyagarov S. Frequency and reasons for falling among residents of the geriatric center [In Hebrew]. Harefuah. 2007;146(8):589-593,647.

10. Tangalos E. Vitamin D and calcium recommendations: making sense of the hype and the reality. Annals of Long-Term Care. 2013;21(8):36-37. www.annalsoflongtermcare.com/article/vitamin-d-calcium-recommendations-hype-reality. Accessed September 4, 2014.

11. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

12. Resnick B, Tangalos E, Morley J. Best Possible Interdisciplinary Post-Acute Management of Falls, Nutrition, Pressure Ulcers and Hydration. Symposium presented at: American Geriatrics Society 2013 Annual Meeting; May 3, 2013; Grapevine, TX. Accessed September 4, 2014.

13. Neyens, JC, van Haastregt JC, Dijcks BP, et al. Effectiveness and implementation aspects of interventions for preventing falls in elderly people in long-term care facilities: a systematic review of RCTs. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(6):410-425.

14. Silva RB, Eslick GD, Duque G. Exercise for falls and fracture prevention in long term care facilities: a systemic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(9):685-689.

15. Durso S, Sullivan G. Geriatrics Review Syllabus. 8th ed. New York, NY: American Geriatrics Society; 2013.

16. Pauly L, Stehle P, Volkert D. Nutritional situation of elderly nursing home residents.

Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;40(1):3-12.

17. Lim SL, Ong KC, Chan YH, Loke WC, Ferguson M, Daniels L. Malnutrition and its impact on cost of hospitalization, length of stay, readmission and 3-year mortality.

Clin Nutr. 2012;31(3):345-350.

18. AMDA. Altered Nutritional Status in the Long-Term Care Setting. Columbia, MD: AMDA; 2010.

19. Van Lancker A, Verhaeghe S, Van Hecke A, Vanderwee K, Goossens J, Beeckman D. The association between malnutrition and oral health status in elderly in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(12):1568-1581.

20. Smoliner C, Norman K, Wagner KH, Hartig W, Lochs H, Pirlich M. Malnutrition and depression in the institutionalised elderly. Br J Nutr. 2009;102(11):1663-1667.

21. Pérez Llamas F, Moregó A, Tóbaruela M, García MD, Santo E, Zamora S. Prevalence of malnutrition and influence of oral nutritional supplementation on nutritional status in institutionalized elderly [In Spanish]. Nutr Hosp. 2011;26(5):1134-1140.

22. Thomas DR. Guidelines for the use of orexigenic drugs in long-term care. Nutr Clin Pract. 2006;21(1):82-87.

23. Lou MF, Dai YT, Huang GS, Yu PJ. Nutritional status and health outcomes for older people with dementia living in institutions. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60(5):470-477.

24. Teno JM, Gonzalo P, Mitchell SL, Kuo S, Fulton AT, Mor V. Feeding tubes and the prevention or healing of pressure ulcers. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(9):697-701.

25. Kuikka LK, Salminen S, Ouwehand A, et al. Inflammation markers and malnutrition as risk factors for infections and impaired health-related quality of life among older nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(5):348-353.

26. Thomas DR, Cote TR, Lawhorne L, et al. Understanding clinical dehydration and its treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9(5):292-301.

27. Collins KA, Presnell SE. Elder neglect and the pathophysiology of aging. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2007;28(2):157-162

28. AMDA. Dehydration and Fluid Maintenance: Clinical Practice Guideline. Columbia, MD: AMDA; 2009.

29. Thomas DR, Tariq SH, Makhdomm S, Haddad R, Moinuddin A. Physician misdiagnosis of dehydration in older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003;4(5):251-254.

30. Weinberg AD, Pals JK, McGlinchey-Berroth R, Minaker KL. Indices of dehydration among frail nursing home patients: highly variable but stable over time. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(10):1070-1073.

31. Bhave G, Neilson EG. Volume depletion versus dehydration: how understanding the difference can guide therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(2):302-309.

32. Mange K, Matsuura D, Cizman B, et al. Language guiding therapy: the case of dehydration versus volume depletion. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(9):848-853.

33. Kayser-Jones J, Schell ES, Porter C, Barbaccia JC, Shaw H. Factors contributing to dehydration in nursing homes: inadequate staffing and lack of professional supervision. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(10):1187-1194.

34. Walsh G. Hypodermoclysis: an alternative method for rehydration in long-term care. J Infus Nurs. 2005;28(2):123-129.

35. Koopmans RT, van der Sterren KJ, van der Steen JT. The ‘natural’ endpoint of dementia: death from cachexia or dehydration following palliative care? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(4):350-355.

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to: Charles A. Cefalu, MD, 1542 Tulane Avenue, Suite 423, New Orleans, LA 70112; ccefal@lsuhsc.edu