What Is Our Ethical Duty to Malingerers?

The number of older adults residing in long-term care (LTC) facilities is expected to increase considerably as the baby-boom generation reaches retirement age. Studies indicate that many psychiatric disorders are more prevalent in older LTC residents than in elders who are community-dwelling.1 With a potential explosion in the need for LTC services and more dependent adults requiring mental health services, healthcare providers may increasingly encounter challenging cases, such as of the elder who exhibits aggressive and abusive behaviors, leading providers to wonder how to handle such elders and what their ethical duties to such individuals are.

We present the challenging case of a 72-year-old man classified as having a personality disorder not otherwise specified (PDNOS), along with almost every feature of antisocial personality disorder. The patient demonstrated particularly aggressive drug-seeking behavior and was eventually admitted to a skilled nursing facility (SNF). At the facility, he attempted to gain access to opiates by continuing his practice of feigning illness and pain. Various treatment strategies were ineffective, and staff at the facility struggled with caring for this malingerer.

Our case scenario highlights the ethical dilemmas that arise in the professional–patient relationship when the patient is a malingerer. A literature search did not provide guidance, as we could not locate any cases of drug addiction and personality disorder among frail older adults, particularly cases of aggressive drug-seeking behavior in this population. With a paucity of information on such cases, it is unclear at what point the rights of a patient and the obligations of the practitioner break down when the patient acts in bad faith. Ethical discussions in medicine usually assume that healthcare providers have an obligation to help patients, but patients are also assumed to be both moral and in need. Questioning healthcare provider obligations, even when a patient’s moral integrity is lacking, can lead to healthcare providers being viewed as abusers of patients and in need of principles and rules to guide their moral behavior and preclude abuses. We examine the medical ethics concepts of patient autonomy, social and professional beneficence, nonmaleficence, and social reciprocity, and discuss how these concepts need to be adapted when the patient does not act in good faith. We also review the challenges of caring for psychiatric patients in dependent care settings, which are subject to regulations established by the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA).

Case Scenario

A 72-year-old man was admitted to the hospital after being treated in the emergency department for opioid and benzodiazepine dependence. A urine drug screen was positive for amphetamine, benzodiazepines, and methadone. The patient was well known to the admitting service for a protracted history of opioid, benzodiazepine, and amphetamine abuse, and opioid-induced depressive mood disorder. He had multiple hospital admissions over a 7-year period, with 22 at one facility and 23 at another, as well as uncounted emergency department visits and outpatient clinic encounters. These admissions were for acute intoxication or suspected overdose of multiple substances, and for suicidal gestures, suicidal threats, and suicidal ideation.

A retrospective review of his medical records revealed patterns that would not be evident by viewing each admission as a single event. We found that the patient’s “overdoses” were largely self-reported and although urine drug screens were positive for multiple substances, levels were not obtained or not documented and he required very little drug treatment for “detoxification.” The patient’s suicidal behavior, used to obtain hospital admission, vaporized shortly after his admissions, when his psychiatrists repeatedly determined that he had no suicidal risk. While at the hospital, the patient demanded opioid medication, and he left the hospital against medical advice on at least eight occasions, usually when he did not get the medication that he demanded. The patient consistently refused to cooperate with his treatment plan or to take the nonopiate pain medications prescribed for him, stating “Morphine is the only thing that works.” On all occasions, he reported his pain as a 10 on a 0–10 pain scale, but without naming a specific location on his body. His functional assessments showed no impairments due to physical pain.

Following his latest admission, once the detoxification protocol was completed and a clinical assessment showed no active suicidal or homicidal ideation, he was transferred to an SNF for social reasons, with specific transfer instructions for no opiates. Immediately upon arrival at the SNF, he began demanding opiates of every passing physician, nurse, and social worker. In pursuit of opiates, he would ambulate rapidly and without difficulty to persistently follow nurses into other patients’ rooms. He repeatedly refused his prescribed pain medications, demanding opiates instead, and on at least one occasion threatened suicide if his demands were not met. When encountering any new covering provider, he would display transiently impaired gait to demonstrate his need for opiates. When he was denied opiates, his gait would return to normal, with a normal, self-selected gait speed.

The patient would demand to be bathed, dressed, groomed, and fed despite being able to perform these tasks himself, as witnessed by his care team. Additionally, he gained >10 lb while in the facility despite not being fed by staff, indicating his ability to nourish himself. He unrelentingly cursed and verbally threatened his therapists and nurses, despite repeated admonitions about inappropriate behavior and the use of security intervention on several occasions. At an interdisciplinary team meeting, he was counseled that he could be discharged from the SNF or arrested if staff pressed legal charges for his threats and assaults. Finally, he conspired with the wife of another patient to abscond against medical advice and was driven to a city several states away, where he presented to another in-patient facility, which had him transported back to his home of record. On his return, he was accepted into a group home, but immediately ransacked the room, vomited copiously on the furnishings, and was brought back to our hospital, where he requested opiates for pain. When opiates were denied, he claimed suicidal ideation. Upon being readmitted to the hospital, his abusive behavior to staff immediately resumed.

Discussion

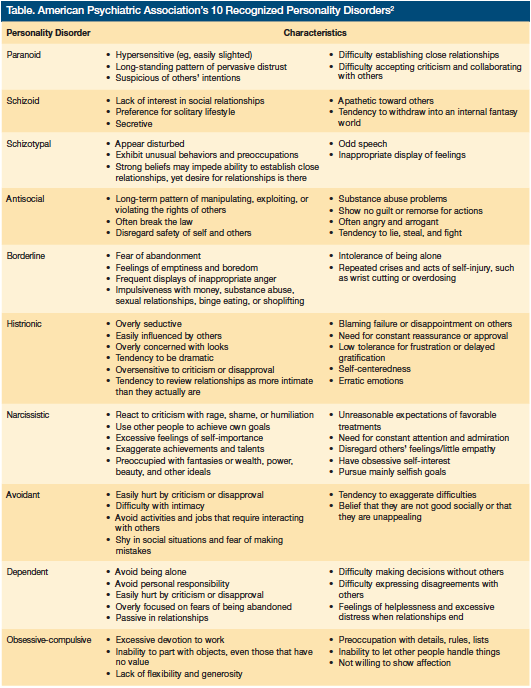

According to the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA’s) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV-TR, PDNOS can be used as a diagnosis when an individual exhibits enough features from more than one of the APA’s 10 recognized personality disorders (Table [click thumbnail for full view]), leading him or her to experience significant distress or impairment in one or more important areas of functioning.2 PDNOS can be diagnosed concomitantly with any of the 10 recognized personality disorders.3 The case patient has PDNOS and every feature of antisocial personality disorder, except that onset in adolescence, noted to be a diagnostic requirement by Sadock and Sadock,4 could not be documented. Despite >45 encounters with the healthcare system over a 7-year period, he has not been relieved of his polysubstance dependency and its emotional consequences, and every effort toward this objective has been ineffective. How do healthcare providers handle such challenging cases and at what point do a healthcare provider’s obligations dissipate?

Ethical discussions in medicine are almost always based on the presumptions that healthcare providers have an obligation to help patients, who for their part are assumed to be both moral and in need. Healthcare providers who question their responsibility to patients risk being viewed in a negative light. While ethical principles in medicine strive to improve patient care and the health of the public by examining and promoting physician professionalism, some of these principles can be impossible to apply when patients are manipulative and do not act in good faith.

Patient Autonomy

The concept of patient autonomy holds that a competent person is at liberty to decide what shall and shall not be done therapeutically.5 The individual may consent to treatment, refuse specific treatments or drugs, and may sign out against medical advice. While a patient has every right to ask his or her healthcare provider for a specific treatment, the healthcare provider is not required to yield to the patient’s requests—or demands—for a “therapy” that is known to be harmful (eg, opioids for a person with opioid-induced mood disorder) or to enroll the patient into a therapeutic program that he or she has no good faith intention of adhering to. Determining that a patient is acting in bad faith is difficult, especially because encounters tend to be handled as isolated, unique events and practitioners may be unfamiliar with a patient’s pattern of behavior. While the patient’s medical record can provide evidence of behavior patterns, it may be difficult to access and impossible to analyze before each new encounter. Even once it is determined that a patient is acting in bad faith, it is unclear if there is any point at which the medical system can be freed from treating him or her; however, at some point, demonstration of bad faith by the patient should liberate the medical system and its individual providers from having to pursue a course of futility.

Beneficence

The concept of beneficence indicates not merely that practitioners should help those with whom they have a professional–patient relationship but, under the related concept of paternalism, may be (at least conditionally) obliged to rescue a patient who is both in diminished capacity and at risk of harm.5 This idea is at least tacitly behind every admission for suicidal ideation. Our case patient’s suicidal ideation, however, was self-reported and ultimately found to be a means for him to manipulate the system. The professional–patient relationship should be a two-way obligation, but the professional–patient obligation always seems to be defined as rights (more recently as “entitlements”) for the patient and as obligations for the professional. Deception and abuse of the professional by the patient seems, for some reason, to be unthinkable to ethicists, and society appears to have no plan of action for those who would abuse healthcare entitlement.

Nonmaleficence

The concept of nonmaleficence is closely entwined with beneficence but serves to give emphasis to the ancient rule “first do no harm.” The rule certainly applies in an active sense; for example, not prescribing opiates to a patient with an opiate-dependent mood disorder. Adherence to this rule can put the practitioner in direct conflict with some patients, such as disingenuous drug-seeking malingerers. Practitioners are also in accord with this rule when they avoid creating risk for a patient through inaction. Therefore, practitioners are ethically obligated to take every threat of suicide seriously, even if it means entertaining every malingerer who utters the word “suicide.”

Social Reciprocity

Social reciprocity means that those who “receive the benefits of society…ought to promote its interests.”5 But what about the situation where social reciprocity breaks down, such as in the case of a patient who is an immoral, dissembling, and intimidating con artist who treats healthcare providers as marks or victims? What are the limits of our ethical responsibility to an abusive, manipulative, malingering patient? There is a need to define a proper balance between societal and professional beneficence and freeloading behavior.

Considerations in Long-Term Care

The case patient was admitted to an SNF for social reasons. Caring for such patients in an OBRA-defined environment is difficult as patient rights and autonomy are major tenets of this overarching law. OBRA, also called the Nursing Home Reform Law, notes that nursing homes are not primarily intended for the care and treatment of individuals with mental illnesses, such as those with personality disorders. OBRA considers an individual to be mentally ill if he or she has a serious mental illness and does not have a primary diagnosis of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease or a related disorder, or a diagnosis (other than a primary diagnosis) of dementia and a primary diagnosis that is not a serious mental illness.6 Some provisions of this law with respect to the treatment of the mentally ill in LTC facilities include6:

• [With certain exceptions] a nursing facility must not admit any new resident who is mentally ill [as defined in the law], unless the state mental health authority has determined (based on an independent physical and mental evaluation) prior to admission that, because of the physical and mental condition of the individual, he or she requires the level of services provided by a nursing facility, [as opposed to those of an institution for mental diseases providing medical assistance to individuals ≥65 years of age] and, if the individual requires [nursing facility] level of services, whether he or she requires specialized services for mental illness. This can prove to be a nice legal point for LTCs that essentially function as step-down units for acute care in-patient hospitals that include psychiatric units.

• A nursing facility must notify the state mental health authority promptly after a significant change in the physical or mental condition of a resident who is mentally ill.

• To the extent needed to fulfill all plans of care, a nursing facility must provide (or arrange for the provision of) treatment and services required by mentally ill residents not otherwise provided or arranged for (or required to be provided or arranged for) by the state.

• [Each] state must have in effect a preadmission screening program, for making determinations for mentally ill individuals who are admitted to nursing facilities.

Take-Home Message

Many geriatricians are unaccustomed to encountering the kind of behavior exhibited by the case patient. When a provider performs a pain assessment (the “fifth vital sign”) based on common guidelines for the management of pain in older adults, there is a general rule that we should always believe our patient’s subjective reporting of pain. Our patient’s case illustrates a need for skepticism and caution when a psychiatric comorbidity is present. Personality disorders often abate in age, but not uniformly nor absolutely; thus, the possibility of malingering is not excluded in the geriatric patient population.

Thought leaders promulgate an interdisciplinary team approach when caring for difficult patients. We used such an approach to care for the case patient. While this approach enabled us to properly assess his physical and mental condition, enact a unified policy regarding his therapeutic regimen, and place limits on his behavior while on the unit, it was not effective in treating his drug dependence or in altering his socially unacceptable behavior. Even effective interdisciplinary clinical teams function within one unit or facility and handle one patient encounter at a time. The case patient would require a large expansion of the concept of team-coordinated care—one that could stretch across multiple encounters and multiple institutions—to have any hope of impact.

Dr. Bishop is an advanced geriatric fellow, and Dr. Chau is program director, Geriatric Medicine Fellowship, University of Nevada School of Medicine, Reno, NV.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Seitz D, Purandare N, Conn D. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older adults in long-term care homes: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(7):1025-1039.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV-TR. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2000.

3. Strack S. Differentiating Normal and Abnormal Personality. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2006.

4. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

5. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 6th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008.

6. Cornell University Law School. Legal Information Institute Website. § 1396r. Requirements for nursing facilities. www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/42/1396r.html. Accessed October 18, 2011.