Trends of 30-Day Hospital Readmissions Among Patients Discharged to Skilled Nursing Facilities From an Academic Practice

Abstract: Patients discharged to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) are at increased risk for repeated hospitalizations. Health care providers are interested in reducing 30-day hospital readmission rates, particularly after the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was implemented. The authors investigated trends in 30-day hospital readmissions among patients discharged to SNFs before and after implementation of the ACA, using interrupted time trend analysis at a community practice of an academic tertiary care center. Thirty-day hospital readmission rates did not change significantly in the study population of patients discharged to SNFs despite implementation of the ACA. Further research is needed to explore the causes underlying these results.

Key words: skilled nursing facilities, hospital readmission, trends

The hospital readmission rate in Medicare beneficiaries is high (19.6%)1 and older adults are at increased risk for detrimental effects associated with hospitalization.2 These readmissions are also expensive and often considered avoidable.3 Studies have shown that discharge to a skilled nursing facility (SNF) is a risk factor for 30-day readmissions.4,5 One study also showed that rates of 30-day hospital readmission from SNFs increased from 18.2% in 2000 to 23.5% in 2006.6 An Office of Inspector General report found that 25% of Medicare SNF residents were hospitalized, and $14.3 billion were spent on readmissions from SNFs in 2011.7 Many of these hospitalizations from SNFs were also potentially avoidable.8-10

The Hospital Readmission Reduction Program, introduced by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), reduced payments to hospitals with excess readmissions, effective for discharges beginning October 1, 201211 As a result, health care providers seem to be more interested in identifying high-risk populations and adopting measures to decrease unplanned readmissions. For example, data from 3387 US hospitals suggests that readmission rates for targeted and nontargeted conditions have decreased from 2007 to 2015.12 Also, an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Health Care Cost and Utilization Project statistical brief indicated that Medicare-covered hospital readmission stays for acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and pneumonia decreased from 2009 to 2013.13 However, it is unclear if these reported improvements are mirrored in the 30-day readmission trends in the authors’ SNFs.

For this study, the authors hypothesized that, after implementation of the CMS program under ACA, the 30-day readmission rates would decrease for patients discharged to their SNFs. Authors analyzed patient data to determine the trend of 30-day hospital readmissions of those discharged to area SNFs from affiliated institutional hospitals. Depending on whether the 30-day readmission trends for these SNFs parallel the reported studies of general improvement, next steps for further improvement in SNF care, or further inquiry into why readmission trends have not improved, will be determined.

Methods

Study Design

An interrupted time series analysis was performed from January 2009 through June 2014 to study the trend in 30-day readmissions in patients who were discharged to an SNF before and after implementation of penalties under the ACA in October 2012.

The study was approved by Mayo Clinic Rochester’s Institutional Review Board.

Participants and Setting

The departments of Family Medicine and the Division of Primary Care Internal Medicine at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, provide post-acute care to patients dismissed from two institutional hospitals to area SNFs. An SNF is defined as having 24-hour nursing coverage and being licensed by the state. One nonprofit facility is affiliated with the parent institution. During the study period, two facilities with the same ownership merged and were treated as one for analysis.

Included patients were those discharged to 10 area SNFs from January 1, 2009, through June 30, 2014. Patients without research authorization and those with an SNF admission date different from the date of hospital dismissal were excluded.

Data Sources

The Mayo Clinic Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for Science of Health Care Delivery collected all data. Mayo Clinic Rochester maintains clinical records from outpatient, inpatient, and SNF provider visits using one electronic health record (EHR) system. Patient registration system data, flow sheets, and laboratory information systems data from the index hospitalization were obtained from the EHR. The International Classification of Diseases (9th revision) diagnosis codes were used to determine comorbid status from billing data. The primary discharge diagnoses were determined using Clinical Classification Software (CCS, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD). Hospitalization status was determined from the EHR and billing data. Mortality data was collected from patient registration system.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was 30-day hospital readmission following discharge from the hospital to an SNF. Hospital inpatient and outpatient billing encounters were cross matched with dismissal summary in the EHR to determine hospital stay. Participants who died prior to 30 days were treated as right-censored in the analysis; ie, death was not considered a readmission event unless readmission occurred prior to death.

Statistical Analysis

An analysis of an interrupted time series was conducted to study the trend in readmissions. The number of 30-day readmissions (y_t) by month since January 2009 was analyzed with the following log-linear, segmented regression model:14

Rt = the number of patient days at risk for our cohort, during the tth month;

t* = the time of intervention (October 2012, in this case);

I(t>t* )=1 if t>t* and 0 otherwise;

xj,t = time varying, confounding variables that authors want to control for (this study had two such variables: x1,t= [average age of the discharged patients during month t] and x2,t= [average severity-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index during month t]);

εt = a correlated error process.

For this analysis, a second-order autoregressive process15 was sufficient for εt.The number of patient days at risk during the tth month, Rt, is the sum of the number of days all patients in the cohort were at risk for a 30-day readmission during the tth month. For example, suppose a patient was discharged to a SNF on March 29. If she did not have a readmission or death within 30 days, then she would contribute 2 days of risk to March and 28 days of risk to April. However, if the patient was readmitted on April 3, then she would contribute 2 days of risk to March and 3 days of risk to April (and contribute to the yt count in April). The same would be true if the patient died on April 3 but would not contribute to the yt count in April. The above model assumes a Poisson response, which is appropriate as the readmissions are count data. The error process, εt allows for both correlation of the counts over time and overdispersion of the Poisson, if needed.16 Parameters in the above model were estimated using the rjags package17 in R.

Results

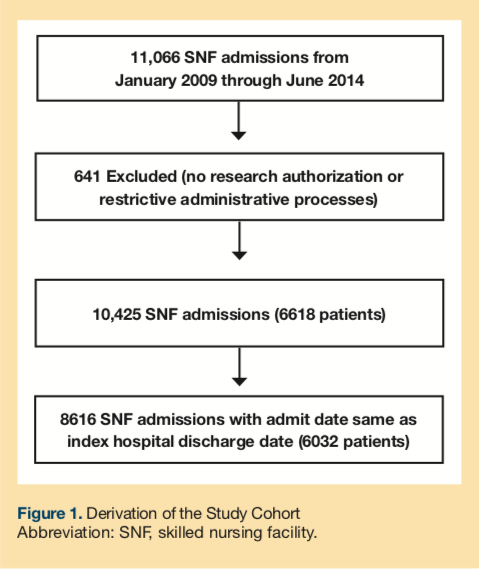

During the study period, 6999 patients were admitted 11,066 times to SNFs; after applying all exclusion criteria, 8616 admission records of 6032 patients were retained for analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the derivation of the study cohort.

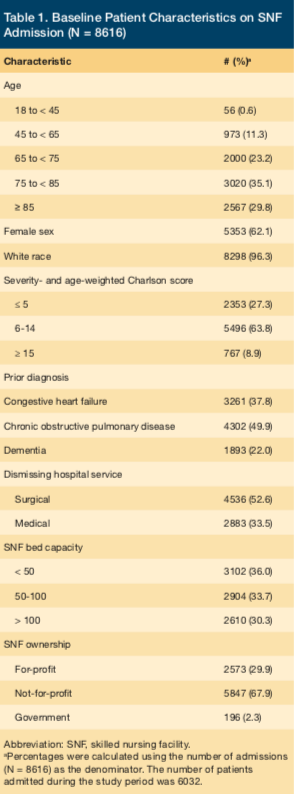

Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of the study population. The mean age was 78.14 years; 88% of the cohort was aged 65 years or older, and 30% were aged 85 years or older. The average age and comorbid status did not change appreciably during the study period and were controlled for as potential confounding variables in the time series analysis.

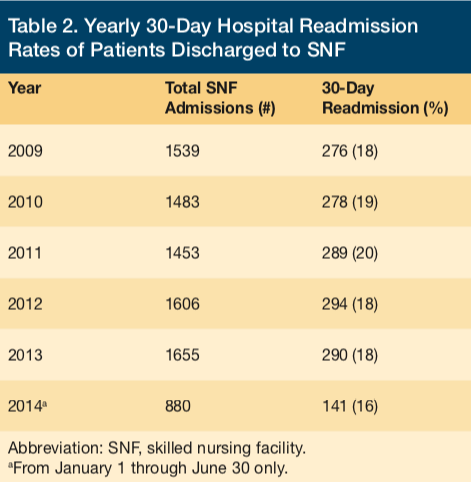

Yearly 30-day hospital readmission rates after discharge to the SNF are shown in Table 2. The overall 1-year mortality rate was 21%.

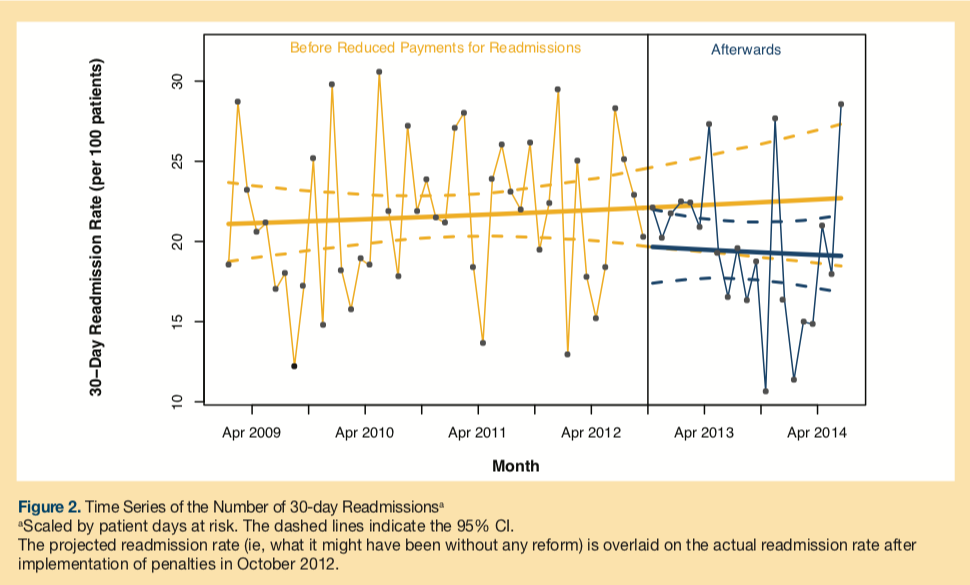

Figure 2 displays the fit of the log-linear, segmented regression model to the data showing 30-day readmission after discharge to a SNF. The estimated readmission rate (y_t) from the period before implementation of ACA penalties is plotted and projected through the end of the study period for perspective (ie, what the rate may have been without the reform). The estimated readmission rate after ACA implementation is also plotted. The change in γ, the 30-day readmission rate after discharge to a SNF immediately after ACA implementation (ie, the difference between curves in November 2012), is estimated to shift slightly downward, but it was not a statistically significant difference, even at an α level of 10%. The change in δ, the 30-day readmission trend (ie, the change in slope of log[λt] over time), also was not statistically significant at a 10% level of significance.

The estimated model indicates that patients discharged to SNFs are still being readmitted at a rate exceeding 19 of 100. The 95% CI indicates that the best rate that may have been achieved by the end of the study period was 17 of 100, and the worst might have been 22 of 100. The monthly observed readmission rates vary between 12% and 30% due to the modest sample sizes (140 discharges to SNF per month on average), and this variation is accounted for by the statistical model.

Discussion

No change was observed in the trend of 30-day hospital readmission rates in this cohort of patients discharged to SNFs from 2009 to June 2014 despite implementation of financial penalties under the ACA beginning October 2012 and despite the overall national trend toward reduced readmissions.12 Several patient, hospitalization, care process, and SNF factors may contribute to this finding, however, the specific reasons for this lack of change are unclear.

In terms of patient factors, patients admitted to SNFs tend to be older, with multimorbidity and functional dependence needs.18,19 Thus, they are at risk for repeated emergency department visits and hospitalizations.5,6 The complexity of patients discharged to SNFs for post-acute care varies, ranging from those with multiple comorbidities needing rehabilitation after surgical procedures to those with multiple end-stage diseases and a tenuous hold on homeostasis. Their care requires a multidisciplinary effort and additional monitoring and interventions compared with those not requiring SNF placement. A large proportion of patients in this study cohort was also discharged from surgical services. Among surgical patients, those determined to need SNF care are more likely to be older and medically complex, and to come with greater comorbid burden. In this cohort (N = 8616), the overall severity and age-weighted Charlson score20 was over 5 in 73% (n = 6263) and over 10 in 31% (n = 2663) of SNF admissions. However, there was no increase in comorbidity over the study period to account for the unchanging trend in 30-day readmissions.

With shorter hospital stays, patients with greater acute care needs are being admitted to SNFs.6 With early discharges, issues that led to patients’ initial hospitalization may not be fully resolved by the time they are admitted to the SNF. In the present study, 37% (n = 586) of the 30-day readmissions (N = 1568) occurred within 7 days of discharge. However, reducing length of hospital stays has not been shown to consistently increase rehospitalization from SNFs.21 Another study reported that readmission diagnosis was the same as index hospital diagnosis in less than half of readmissions from the SNFs, suggesting that the presence of multiple comorbidities in patients contributed to this outcome.22

Care processes, such as transition interventions to reduce readmissions, may need to be modified for patients that are discharged to SNFs. Currently, measures implemented within care processes to prevent readmissions sometimes target specific conditions that require active engagement by the patient and frequently involve multidisciplinary outpatient primary care or care transitions teams. Such measures may not always be practical, as patients discharged to SNFs can have multiple active conditions and may be unable to fully participate in self-care strategies, and some facilities may lack multidisciplinary care teams. Interventions to reduce readmissions by the post-acute practice in this study have not specifically targeted SNF patients, and it is unclear if the intensity of transition management was the same as outpatient care transition interventions. Results from this study suggest that care transition interventions to reduce readmissions may need to be modified for patients that are discharged to SNFs; further research is needed.

Discharging units of hospitals may be unfamiliar with the nuances of the SNF environment, staffing, and capabilities and may assume more clinical surveillance than exists. These SNF factors contribute to the risks involved when older adults are discharged and transition to an SNF. For example, the hand-off may not include pertinent, and sometimes critical, clinical information. Acceptance of patients by SNFs may be initially coordinated by social workers, and, because of inadequate communication between clinical teams and lack of access to medical records, SNFs may accept patients whose needs they cannot meet. Shorter hospital stays translate into SNFs admitting patients with greater acute care requirements, yet staffing and regulatory visit requirements have not changed to accommodate this situation.23 Clinical assessment, medication reconciliation, review of acute and chronic active conditions, and discussions about goals of care with a physician may not occur until the initial comprehensive visit several days after admission to the SNF, even for patients who received intensive critical care during hospitalization. Health care providers have explored interventions such as frequent visits by providers and their greater onsite availability, goals-of-care discussions, access to hospital medical records, and enhanced communication with the hospital and facility staff to reduce 30-day readmissions from SNFs.24 Further research is needed to confirm whether similar interventions are effective in other health systems and geographic locations.

SNFs vary considerably regarding factors such as ownership, culture, quality, and services offered. Workforce issues with regard to staffing levels and staff turnover may influence outcomes25-28 and contribute to the transition risks mentioned above. The associations between facility quality and readmission rates have been studied with varying results. In one study on fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries discharged to SNFs after acute hospitalization, available SNF performance measures were not associated with differences in adjusted risk of readmission consistently,29 while another study reported that patients receiving care in nursing homes with higher staffing levels and lower deficiency scores were less likely to be rehospitalized.30 Another issue is the lack of alignment of incentives for reducing hospital readmissions. To address this concern, CMS added 30-day hospital readmission to quality metrics for certified SNFs, and, under the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program, they introduced performance-based financial consequences for SNFs.31,32 These changes may provide impetus for SNFs to be more engaged in measures to avoid readmissions. Currently, though, it is unclear if these changes will affect the 30-day hospital readmission rates in patients discharged to SNFs. There is now some national data, available as quality measure benchmarks, on the risk-adjusted rate of all-cause, unplanned hospital readmissions within 30 days for accountable care organizations assigned beneficiaries who were admitted to SNFs after discharge from their proximal hospitalization.33

Cumulatively, the results of this study have many practical implications for other institutions and providers. They suggest a need to continue to evaluate trends of unplanned health care utilization in patients discharged to SNFs. Results also suggest that care transition interventions for complex older patients may need to be modified for those that are discharged to SNFs. Further research is needed to determine factors that increase risk of hospital readmission in patients discharged to SNFs and to determine effective interventions to reduce this outcome.

This study has potential limitations as a retrospective analysis and with its use of administrative data. Patients were assessed from a single teaching institution, serving a small number of SNFs with a largely white population. These factors limit the generalizability of the study findings. In addition, it was not easy to clearly distinguish the short-term SNF residents (with expectations of dismissal) from the long-term residents; only patients whose SNF admission was linked to an index hospitalization at one of the institutional hospitals were included, so all SNF admissions were “post-acute.” Some outcome events were also potentially lost if they occurred at another facility. An additional limitation is that a floor effect on readmission rates could not be ruled out, as it was not known whether the readmissions were avoidable and the extent to which unavoidable readmissions contributed to the unchanging trend. Finally, although providers have been aware of the implications of ACA prior to its implementation in October 2012, it is possible that this analysis was conducted too soon following its implementation to capture a significant change in trend. Follow up after more time has passed may be needed.

Conclusion

No significant change was observed in 30-day hospital readmission rates for patients discharged to SNFs for post-acute care from January 2009 to June 2014 in the study population despite implementation of ACA in October 2012. In-depth research is needed to explore the causes underlying these results—which may be mirrored at other facilities—that do not line up with research reporting general improvement nationally. Continued research from other institutions and geographic areas is needed to determine whether the ACA mandates and penalties have influenced the trends in 30-day readmission rates for patients discharged to SNFs.

To read more articles in this issue, visit the 2017 November/December issue page

To read more ALTC expert commentary and news, visit the homepage

References

1. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428.

2. Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(3):219-223.

3. Segal M, Rollins E, Hodges K, Roozeboom M. Medicare-Medicaid eligible beneficiaries and potentially avoidable hospitalizations. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(1). pii: mmrr.004.01.b01. doi:10.5600/mmrr.004.01.b01

4. Silverstein MD, Qin H, Mercer SQ, Fong J, Haydar Z. Risk factors for 30-day hospital readmission in patients ≥65 years of age. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2008;21(4):363-372.

5. Bogaisky M, Dezieck L. Early hospital readmission of nursing home residents and community-dwelling elderly adults discharged from the geriatrics service of an urban teaching hospital: patterns and risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(3):548-552.

6. Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(1):57-64.

7. US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG). Medicare nursing home resident hospitalization rates merit additional monitoring. HHS OIG website. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-06-11-00040.pdf. Published November 2013. Accessed November 1, 2017.

8. Walsh EG, Wiener JM, Haber S, Bragg A, Freiman M, Ouslander JG. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations of dually eligible Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries from nursing facility and Home- and Community-Based Services waiver programs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(5):821-829.

9. Ouslander JG, Naharci I, Engstrom G, et al. Hospital transfers of skilled nursing facility (SNF) patients within 48 hours and 30 days after SNF admission. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(9):839-845.

10. Ouslander JG, Naharci I, Engstrom G, et al. Root cause analyses of transfers of skilled nursing facility patients to acute hospitals: lessons learned for reducing unnecessary hospitalizations. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(3):256-262.

11. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Readmissions reduction program (HRRP) CMS website. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Updated April 18, 2016. Accessed November 1, 2017.

12. Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital readmissions reduction program. New Engl J Med. 2016;374:1543-1551.

13. Fingar K, Washington R. Trends in Hospital Readmissions for Four High-Volume Conditions, 2009–2013. HCUP Statistical Brief #196. Published November 2015. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb196-Readmissions-Trends-High-Volume-Conditions.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2017.

14. Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299-309.

15. Brockwell PJ, Davis RA. Time Series: Theory and Methods. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2006.

16. Zeger SL. A regression model for time series of counts. Biometrika. 1988;75(4):621-629.

17. Plummer M. JAGS: a program for analysis of Bayesian graphical models using Gibbs sampling. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Distributed Statistical Computing; 2003.

18. Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, et al. Long-term care providers and services users in the United States: data from the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers, 2013-2014. Vital Health Stat 3. 2016;(38):x-xii; 1-105.

19. Messinger-Rapport BJ, Gammack JK, Little MO, Morley JE. Clinical update on nursing home medicine: 2014. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(11):786-801.

20. Singh B, Singh A, Ahmed A, et al. Derivation and validation of automated electronic search strategies to extract Charlson comorbidities from electronic medical records. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(9):817-824.

21. Unruh MA, Trivedi AN, Grabowski DC, Mor V. Does reducing length of stay increase rehospitalization of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries discharged to skilled nursing facilities? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(9):1443-1448.

22. Ouslander JG, Diaz S, Hain D, Tappen R. Frequency and diagnoses associated with 7- and 30-day readmission of skilled nursing facility patients to a nonteaching community hospital. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(3):195-203.

23. US Government Publishing Office, Electronic code of Federal Regulations (ECFR). §483.40 Behavioral health services. ECFR website. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=2518cbf6ef84a10509807fff25db8de8&mc=true&node=se42.5.483_140&rgn=div8. Published October 4, 2016. Updated October 30, 2017. Accessed November 1, 2017.

24. Kim LD, Kou L, Hu B, Gorodeski EZ, Rothberg MB. Impact of a connected care model on 30-day readmission rates from skilled nursing facilities. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(4):238-244.

25. Harrington C, Schnelle JF, McGregor M, Simmons SF. The need for higher minimum staffing standards in U.S. nursing homes. Health Serv Insights. 2016;9:13-19.

26. Bostick JE, Rantz MJ, Flesner MK, Riggs CJ. Systematic review of studies of staffing and quality in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7(6):366-376.

27. Castle NG, Engberg J, Men A. Nursing home staff turnover: impact on nursing home compare quality measures. Gerontologist. 2007;47(5):650-661.

28. Thomas KS, Mor V, Tyler DA, Hyer K. The relationships among licensed nurse turnover, retention, and rehospitalization of nursing home residents. Gerontologist. 2013;53(2):211-221.

29. Neuman MD, Wirtalla C, Werner RM. Association between skilled nursing facility quality indicators and hospital readmissions. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1542-1551.

30. Thomas KS, Rahman M, Mor V, Intrator O. Influence of hospital and nursing home quality on hospital readmissions. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(11):e523-e531.

31. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The skilled nursing facility value-based purchasing program (SNFVBP). CMS website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Other-VBPs/SNF-VBP.html. Updated September 28, 2017. Accessed November 1, 2017.

32. National Archives and Records Administration, Federal Register. Medicare program; prospective payment system and consolidated billing for skilled nursing facilities proposed rule for FY 2017, SNF value-based purchasing program, SNF quality report program, and SNF payment models research. Federal Register website. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/04/25/2016-09399/medicare-program-prospective-payment-system-and-consolidated-billing-for-skilled-nursing-facilities. Published April 25, 2016. Accessed November 1, 2017.

33. Accountable Care Organization 2015 Program Analysis Quality Performance Standards Narrative Measure Specifications, Reference Section 2.2.2 regarding ACO 35: Skilled Nursing Facility 30-Day All-Cause Readmission. Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/2017-Reporting-Year-Narrative-Specifications.pdf. Published January 5, 2017. Accessed November 20, 2017.