Transitioning Nursing Home Patients with Dementia to Hospice Care: Basics, Benefits, and Barriers

Despite the increasing elderly population, growing nursing home use, and the prevalent diagnosis of dementia among deceased residents, hospice remains an underused option for elderly nursing home residents with a primary diagnosis of dementia. The authors explore the potential benefits of transitioning these patients to hospice care, and review the criteria for initiating hospice, examine barriers that preclude hospice admission, and offer suggestions to overcome these barriers.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

In 2010, there were 40 million elderly individuals residing in the United States, and this number is anticipated to grow to 55 million by 2020.1 As a result of this growth, an increasing number of older adults will require long-term care (LTC) services. Because most nursing home residents have multiple chronic conditions,2 it is common for these individuals to live the last phase of their lives in LTC facilities, and is estimated that 2 out of 5 Americans will die in a nursing home by 20203. More than half of nursing home residents have a dementia diagnosis prior to their death.4 Studies have shown hospice care to be the ultimate treatment modality for these patients, but this is not a widely used alternative.5,6 Because dementia is a life-limiting illness and hospice services are centered on caring for patients with such illnesses, we explore the potential benefits of transitioning elderly nursing home residents with a primary diagnosis of dementia to hospice care. This article examines the criteria for initiating hospice in these patients, providing 2 short case scenarios that put these criteria into perspective; assess barriers that preclude hospice admission; and offer suggestions to overcome these barriers.

Case Scenarios

Mr. R is an 80-year-old nursing home resident with a long-standing history of Alzheimer’s disease. Over the past 5 months, his food intake has decreased, despite taking an appetite stimulant and being fed by the staff. He was admitted to a nearby hospital 2 months earlier for aspiration pneumonia and currently has a stage III sacral ulcer. He does not speak any intelligible words, stays in bed most of the time, and tolerates sitting in a wheelchair for less than an hour on some days.

Ms. S is an 85-year-old resident who lives in the same nursing home and also has Alzheimer’s disease. Over the past 6 months, she has been treated for recurrent lower urinary tract infections (UTIs). Occasionally, she is found wandering in the hallways, and she has frequent periods of agitated behavior in the early evenings. Her spoken words are limited to “yes” and “no.” She is totally dependent on the nursing home staff with regard to feeding, and her weight has dropped from 148 lb to 137 lb over the past 3 months.

Which of these patients qualifies for the Medicare Hospice Benefit? How soon should hospice care be initiated?

Hospice in America

Hospice is a model of care centered on patients with life-limiting illnesses. Physical, psychological, social, and spiritual aspects of suffering are thoroughly managed by an interdisciplinary team, which typically comprises a physician, registered nurse, medical social worker, chaplain, nursing aides, and volunteers. Patients with malignancies led other patients as the most frequent beneficiaries of hospice care when the movement took off in America in the 1970s. In recent years, however, only 38.3% of hospice admissions were for a primary diagnosis of cancer.7 A report by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization in 2008 revealed that 61.7% of individuals admitted to hospice had diseases other than cancer, with debility unspecified, heart disease, and dementia being the top 3 diagnoses.7

Medicare Coverage

In 1983, the Medicare Hospice Benefit was established for patients with illnesses that reduce their life expectancy to 6 months or less if the illness runs its normal course.8 It provides for nursing care, medical social services, physicians’ services, counseling services, short-term inpatient care, medical appliances and supplies, and physical, occupational, and speech therapy. Special services that are also covered include continuous home care, bereavement counseling, and special treatment modalities (eg, chemotherapy, radiation therapy).

To receive full coverage, an individual must be entitled to Medicare Part A, must waive all rights to other Medicare payments for the duration of hospice care, and must be certified as being terminally ill by 2 physicians. Upon enrollment, an initial 90-day period is given. If the patient survives and is deemed to still fulfill the appropriate criteria, another 90-day period is accorded, and the patient becomes eligible for an unlimited number of 60-day periods thereafter.

The Medicare Hospice Benefit was originally created to serve community-dwelling individuals. This changed in 1986 when the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 extended the hospice benefit to Medicare beneficiaries living in nursing homes.9 Residents deemed terminally ill were made eligible to receive hospice care from Medicare-approved hospice providers that partnered with nursing homes. As a result, hospice admissions in the nursing home setting have gradually increased. A study assessing hospice services administered at home versus in nursing homes found that nursing home hospice patients are more likely to have a primary noncancer discharge diagnosis, such as dementia or heart disease, than individuals receiving hospice care at home.10

Criteria for Admission

The criteria for initiating hospice care in patients with dementia, including end-stage Alzheimer’s disease, were defined by Stuart and associates11 and subsequently implemented by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization in 1995. Reisberg’s dementia-specific staging system, the Functional Assessment Staging (FAST; Table 1)12 served as the backbone of the criteria, with a score of 7C considered as hospice admissible. Other important accompanying conditions that support the aforementioned criteria were a diagnosis in the past 3 to 6 months of aspiration pneumonia, pyelonephritis, or upper UTI; septicemia; multiple decubitus ulcers (stage III or IV); recurrent fever even after the use of antibiotics; and nutritional issues (eg, difficulty swallowing or refusal to eat such that sufficient fluid or caloric intake cannot be maintained; patient refusal of artificial nutrition; evidence of an impaired nutritional status, as demonstrated by a loss of body weight of 10% or morein a patient receiving artificial nutritional support).13

Benefits of Hospice

Several studies have shown hospice to be a favorable option in the care of terminally ill nursing home residents. Surveys involving families of patients enrolled in hospice have consistently demonstrated increased satisfaction in terms of improved care, decreased hospitalizations, and fewer days spent in an acute care setting.14-16Closely associated with the benefit of reduced hospitalizations is substantial savings for the government. Gozalo and associates17 found that both Medicare and Medicaid expenditures decreased, especially among short-stay patients who were dying.

Patients who are terminally ill are provided with more intense and comprehensive palliative care interventions through hospice.18-20Assistance with basic facets of care is also better facilitated by trained hospice staff. Support with all of these essential services come at a time when family members and nursing home staff alike are challenged with all the pressing needs related to the dying process.

Another area where hospice care excels is family support.21,22 Teno and colleagues22 concluded that a large number of patients dying in institutions have unmet needs for symptom amelioration, physician communication, emotional support, and being treated with respect. The investigators found that bereaved family members of patients who benefited from hospice care had higher satisfaction rates, as there were fewer unmet needs or concerns regarding care.

Barriers to Initiating Hospice

Several barriers to initiating hospice care for residents with dementia have been identified. These barriers may stem from factors related to healthcare professionals, institutions, finances, and patients and families.

Health Professionals–Centered

Late referral is the main health professionals–centered barrier to initiating hospice for residents with dementia.19,20,23 This barrier might stem from difficulty predicting survival time, poor recognition of terminal illness, and failure or difficulty in eliciting hospice preferences from patients or their families. The principals involved in patient care, especially the attending physician, might lack knowledge about the admission criteria and enrollment procedures, and misunderstandings about the role and scope of hospice are fairly common. In addition, the lack of the do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders in the admission process often creates considerable confusion.

The challenge of discussing hospice with patients and families is widely recognized.24 Physicians may be hesitant to have frank discussions with patients and their families when prognosis is poor and treatment options are diminished.

In some cases, the FAST score–centered hospice admission criteria alone might keep a patient from being admitted. An important study by Luchins and associates25 that examined the FAST 7C enrollment cutoff revealed that 41% of the nursing home residents in the study could not be accurately scored. This finding represents a dilemma for patients who do not follow the precise progression of features described in the scale, which may inhibit hospice initiation.

Institution-Centered

A significant barrier to hospice is facility reluctance.26 This barrier may come from nursing home administrators, who may regard the initiation of hospice care by a partnered hospice provider as an admission of their own facility’s inadequate end-of-life care. Sharing this lack of enthusiasm may be the nursing staff and physicians, who are focused on restorative strategies in the nursing home setting, especially because regulatory standards emphasize rehabilitation.

Finance-Centered

With current Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement regulations, nursing homes face financial disincentives to promote hospice over skilled nursing care.26 Medicare prohibits simultaneous use of Part A for skilled nursing facility (SNF) stay and the Medicare Hospice Benefit. SNF patients with private coverage are required to pay privately for room and board while receiving hospice care. For patients with both Medicare and Medicaid, the nursing home is paid by the hospice provider for room and board at a much lower rate. This might affect hospitalized patients who are eligible for both benefits and are getting ready for transfer to a facility with both capabilities, as well as for SNF patients who may qualify for hospice transition.

An additional financial deterrent is the uniformity of payment offered by Medicare. This raises the possibility of a potential nonproportional relationship between the intensity of care provided by nursing homes and the resulting Medicare reimbursement. In addition, suspicions of fraudulent practices with aims of financial gain have been raised, but will not be discussed in this article.

Patient- and Family-Centered

A survey among primary care physicians cited patient and family readiness as the major barrier to earlier hospice referrals.27 Primary factors contributing to the reluctance of family members are insufficient knowledge and misconceptions about hospice care.28 The notion that hospice is employed only when the patient is in the last stages of dying is certainly pervasive. Another common misconception is that being under hospice care is tantamount to “giving up.” In addition, many caregivers believe that their optimistic goals are extinguished by initiating hospice.

Overcoming the Barriers

Barriers to initiating hospice care for residents with dementia can be overcome. We outline steps that can be taken in each case to help ensure dementia patients requiring hospice receive this care.

Health Professionals–Centered

We strongly believe that knowledge is the main driving force in increasing the number of nursing home residents with dementia who are transitioned to hospice care. Casarett and colleagues29 state that targeted educational efforts are necessary to encourage early referral. The criteria adopted by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization are recognized by all hospice providers and should be made known to all administrative, medical, and nursing staff, along with the nature, function, and goals of hospice care.

Of equal importance is providing hospice education to family members and even nursing home residents who are still cognitively intact. A study by Casarett and colleagues15 showed that a simple communication intervention identified patients who preferred hospice care, and this led to increased hospice referral rates and increased satisfaction with end-of-life care among families. Health professionals are encouraged to discuss hospice with patients and their families so that their preference can be determined early on.

Each resident’s legal representative should be made known to the nursing home staff. This would avert any form of delay in starting hospice care for a patient who is unable to verbalize his or her wishes. Although many patients receiving hospice care have DNR status, it should be clear to all involved health professionals that this is not a requisite for admission. Medicare disallows hospice agencies from requiring patients to have a DNR order in place prior to enrollment.

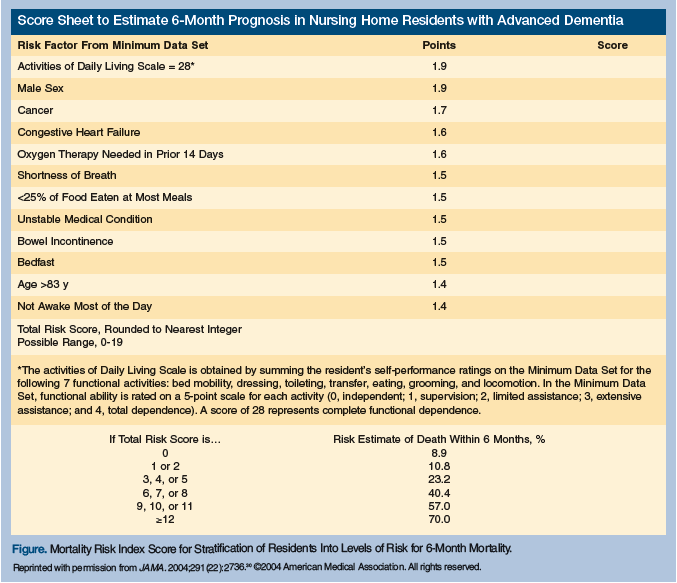

An alternate tool to estimate prognosis may be used by health professionals to help gauge hospice appropriateness. One such instrument that predicts 6-month mortality risk was developed by Mitchell and associates30 for nursing home patients with advanced dementia. Using data from the Minimum Data Set (MDS) of each subject, 12 variables were identified and factored into a mortality risk score (Figure) that was found to be more accurate than using a FAST 7C cutoff. This valuable prognostic index may play an important role in advocating hospice initiation, especially for patients who do not follow the FAST sequence.

Institution- and Finance-Centered

Successful policy changes are vital in overcoming the previously mentioned financial obstructions and unsupportive attitudes toward hospice.31 State surveyors can scrutinize decedents from nursing homes and identify deficits in end-of-life care. Medicare may look into granting coverage of hospice benefits, including room and board, without potential penalties for patients and nursing homes. It may also examine making reimbursements more congruent with the intensity of services provided to the terminally ill. State Medicaid programs also should be encouraged to institute their own palliative care or hospice benefit.

Recognizing the issues involved in skilled nursing and hospice care, we propose several measures that might ease transition to hospice. As part of hospital discharge planning, attending physicians and case managers should facilitate the transfer of financially qualified patients with advanced dementia and no foreseen rehabilitation potential to long-term care instead of SNF. If this is not possible, SNF patients may be given a reasonable trial of rehabilitation, and once this fails, hospice should be strongly considered. In connection with this, both physicians and nursing home leadership can implement a program reflecting the hospice admission criteria, as well as the mortality risk index, aimed at actively monitoring SNF patients for hospice readiness. Finally, the SNF nursing staff should be trained to provide basic hospice care to patients until they are fully transitioned to hospice.

Patient- and Family-Centered

Nursing home staff, especially physicians, must have effective communication skills. In addition to conveying prognosis to family members with clarity and empathy, it is also important to address their concerns, apprehensions, and misconceptions about hospice. Family members and caregivers, especially the chief decision maker, should be encouraged to establish a relationship with the hospice team earlier in the course of treatment so as to allow ample time for them, the patient, and the hospice team to develop a meaningful partnership.

A huge hurdle that must be overcome is the common misperception that hospice is the equivalent of abandoning care. The physician must stress that discontinuation of all existing medications and other treatment methods is not a prerequisite to starting hospice care, and that hospice entitles the patient to a wide array of interventions aimed at ensuring comfort.

With regard to the sensitive topic of hope, Russell and LeGrand28 recommended that hope may be refocused on more realistic goals. This might be accomplished by telling the caregivers and family members that instead of hoping for a cure, they should hope for diminished pain and suffering and for good quality time spent with the patient, as these are more realistic and appropriate goals at this point. Table 2 provides a summary of the barriers to initiating hospice care along with the appropriate recommendations for overcoming them.

Resolution of Case Scenarios

Because Mr. R is unable to speak any intelligible words and ambulate independently, he is at least at FAST stage 7C. He also has several comorbid conditions, such as a stage III decubitus ulcer, recent aspiration pneumonia, and altered nutritional status. As a result, he qualifies for the Medicare Hospice Benefit, and needs to be transitioned at the soonest possible opportunity. On the other hand, Ms. S is probably at FAST stage 7A (speech ability limited to about a half-dozen intelligible words), which does not meet the hospice criteria. Using the mortality risk index, the patient’s score is 1.4 (age >83 years), conferring a 10.8% risk of dying within the next 6 months. Efforts should be made to optimize her current level of care, including fall precautions, continued nutritional support, and appropriate treatment for wandering, sundowning, and frequent UTIs. The basics, benefits, and provisions of hospice care, as well as the patient’s prognosis, should be clearly communicated to her family members, and their preference for hospice care should be made known to all healthcare providers. All of these tasks need to be accomplished to guarantee a seamless transition when the time is appropriate.

Conclusion

Despite the increasing elderly population, use of LTC services, and prevalence of dementia diagnoses among deceased LTC residents, hospice continues to be anunderutilized treatment option for LTC patients with dementia. Initiating hospice care has been shown to be beneficial to these patients and their families, and even results in economic gains; thus, LTC facilities should make every effort to ensure that all residents with dementia who qualify for hospice care receive this valuable care option.

Dr. Samala is a clinical fellow, Dr. Galindo is staff, and Dr. Ciocon is chairman, Department of Geriatrics, Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston.

References

1. Administration on Aging, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. A Profile of Older Americans: 2005. www.aoa.gov/AoAroot/Aging_Statistics/Profile/Index.aspx. Accessed August 14, 2010.

2. Harrington C, Carillo H, Wellin V. Nursing Facilities, Staffing, Residents and Facility Deficiencies, 1994-2000. San Francisco: Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, University of California; 2000.

3. Brock D, Foley D. Demography and epidemiology of dying in the U.S. with emphasis on deaths of older persons. Hosp J. 1998;13(1-2):49-60.

4. Travis SS, Loving G, McClanahan L, Bernard M. Hospitalization patterns and palliation in the last year of life among residents in long-term care. Gerontologist. 2001;41(2):153-160.

5. Stevenson D, Bramson J. Hospice care in the nursing home setting: a review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(3):440-451.

6. Han B, Tiggle R, Remsburg R. Characteristics of Patients Receiving Hospice Care at Home Versus in Nursing Homes: results from the National Home and Hospice Care Survey and the National Nursing Home Survey. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2008; 24(6):479-486.

7. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America, 2009 Edition. Accessed November 19, 2010.

8. Medicare Benefit Policy Manual. Chapter 9-Coverage of Hospice Services Under Hospital Insurance. www.cms.gov/manuals/Downloads/bp102c09.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2010.

9. Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (Cobra-85), (P.L. 99-72). www.ssa.gov. Accessed November 19, 2010.

10. Han B, Tiggle RB, Remsburg RE. Characteristics of patients receiving hospice care at home versus in nursing homes: results from the National Home and Hospice Care Survey and the National Nursing Home Survey. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2007;24(6):479-486.

11. Stuart B, Herbst L, Kinsbrunner B, et al. Medical Guidelines for Determining Prognosis in Selected Non-Cancer Diseases. 1st ed. Arlington, VA: National Hospice Organization; 1995.

12. Reisberg B. Functional Assessment Staging (FAST). Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24(4):653-659.

13. Kinzbrunner B, Weinreb N, Policzer JS, Weiss BD, eds. 20 Common Problems: End-of-Life Care. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2002.

14. Baer WM, Hanson LC. Families’ perception of the added value of hospice in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(8):879-882.

15. Casarett D, Karlawish J, Morales K, et al. Improving the use of hospice services in nursing homes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294(2):211-217.

16. Gozalo PL, Miller SC. Hospice enrollment and evaluation of its causal effect on hospitalization of dying nursing home patients. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):587-610.

17. Gozalo PL, Miller SC, Intrator O, et al. Hospice effect on government expenditures among nursing home residents. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(1 Pt 1):134-153.

18. Keay TJ, Schonwetter RS. Hospice care in the nursing home. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57(3):491-494.

19. Miller SC, Teno JM, Mor V. Hospice and palliative care in nursing homes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2004;20(4):717-734.

20. Munn JC, Hanson LC, Zimmerman S, et al. Is hospice associated with improved end-of-life care in nursing homes and assisted living facilities? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(3):490-495.

21. Murphy K, Hanrahan P, Luchins D. A survey of grief and bereavement in nursing homes: the importance of hospice grief and bereavement for the end-stage Alzheimer’s disease patient and family. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(9):1104-1107.

22. Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291(1):88-93.

23. Wetle T, Shield R, Teno J, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care experiences in nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2005;45(5):642-650.

24. Casarett DJ, Quill TE. “I’m not ready for hospice”: strategies for timely and effective hospice discussions. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(6):443-449.

25. Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P, Murphy K. Criteria for enrolling dementia patients in hospice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(9):1054-1059.

26. Stevenson DG, Bramson JS. Hospice care in the nursing home setting: areview of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(3):440-451.

27. Ogle K, Mavis B, Wang T. Hospice and primary care physicians: attitudes, knowledge and barriers. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2003;20(1):41-51.

28. Russell KM, LeGrand SB. ‘I’m not that sick!’ Overcoming the barriers to hospice discussions. Cleve Clin J Med. 2006;73(6):517-524.

29. Casarett DJ, Hirschman KB, Henry MR. Does hospice have a role in nursing home care at the end-of-life? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(11):1493-1498.

30. Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB, et al. Estimating prognosis for nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2734-2740.

31. Zerzan J, Stearns S, Hanson L. Access to palliative care and hospice in nursing homes. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2489-2494.