Top 10 Patient Safety Concerns, 2018

ECRI Institute and Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging (ALTC) have joined in collaboration to bring ALTC readers periodic articles on topics in risk management, quality assurance and performance improvement (QAPI), and safety for persons served throughout the aging services continuum. ECRI Institute is an independent nonprofit that researches the best approaches to improving health care.

Health care is striving to become an industry of high-reliability organizations,1 and part of being in the high-reliability industry means staying vigilant and identifying problems proactively.2 ECRI Institute’s annual Top 10 list of patient safety concerns helps organizations around the world and across the continuum of care identify looming patient safety challenges and offers suggestions and resources for addressing them.

How We Identify Concerns

Since 2009, the ECRI Institute Patient Safety Organization (PSO) and our partner PSOs have received more than 2 million event reports. Event reports include adverse events, incidents, near misses, root-cause analyses, and organizational assessment recommendations, all of which provide excellent sources of data to help increase safety, reduce risk, and improve quality for all stakeholders across health care. That means that the 10 patient safety concerns on this list are very real, and they are causing harm—often serious harm—to real people. In selecting this year’s patient safety concerns list,3 ECRI Institute relied not only on data regarding events and safety concerns but also on expert judgment from the ECRI Institute PSO Expert Advisory Panel, ECRI Institute analysts, and other subject matter experts who offered their input on which hazards were most impactful and in need of attention.

But this is not an exercise in simple tabulation; the list does not necessarily represent the issues that occur most frequently or are most severe. Most organizations already know what their high-frequency, high-severity challenges are. Rather, this list identifies concerns that might be high priorities for other reasons, such as new risks, existing concerns that are changing because of new technology or care delivery models, and persistent issues that need focused attention or pose new opportunities for intervention.

In this column, we present a detailed look at workarounds, the fourth item on this year’s list. Workarounds are present across all care settings, including aging services. Even though workarounds can lead to most other kinds of hazards on the list, they can be difficult to detect; compounding this harm, when workarounds become “the way we do things here,” they can mask systems flaws and make it harder for organizations to become safer.

Some of the other items that made the list are also highlighted briefly below, as they are of particular interest in aging services organizations. For the full list of patient safety concerns, see Table 1.

Workarounds

Workarounds are pervasive in health care.3 They occur when staff bend work rules to circumvent or temporarily fix a real or perceived barrier or system flaw. Sometimes, staff resort to workarounds when they are dealing with exceptional patient care circumstances.4

A workaround is “something that the clinician does to make the process easier,” explained Kelly C Graham, RN, patient safety analyst and consultant, ECRI Institute. The staff member’s intent is to help the patient, she said, as numerous events submitted to ECRI Institute PSO’s database illustrate. In 1 case, a nurse overrode an automated medication dispensing cabinet to retrieve medications for severe agitation and anxiety to be administered to a patient who was exhibiting dangerous behaviors but was not yet admitted to the organization. An override of an automated dispensing cabinet enables a staff member to bypass pharmacy screening and verification of a patient’s medication order. Because the patient was not yet registered in the computer system, the pharmacy would not have been able to verify the order. Pharmacy review, which can include most “stat” orders, typically occurs before a drug is removed from a dispensing cabinet. Although this workaround circumvented the organization’s medication-use policy, the outcome was positive because the patient became less anxious. But, in general, the use of overrides can lead to harm if staff obtain a medication before a pharmacist has verified that the patient does not have a contraindication, such as a documented allergy to the medication, said Ms Graham.

ECRI Institute PSO has received numerous reports of dispensing cabinet overrides as well as other workarounds involving technology, such as bar-code medication administration systems, electronic health record systems, and computerized provider order entry systems.

Other event reports describe workarounds with routine processes, such as failing to use 2 patient identifiers or to label a specimen container in the patient’s presence. For example, some events describe staff printing several patient labels at one time to eliminate multiple trips to a printer, but this workaround increases the risk of specimen mislabeling.

As workarounds become entrenched in unit-level work, they are difficult to detect. The incorrect procedure gets passed from one staff member to another. “We hear, ‘It’s the way we do things here.’ That’s not good,” said Ms Graham. Instead of alerting someone to the problem underlying the behavior, staff may permit the unsafe conditions to continue until someone is harmed.

Fortunately, Ms Graham said that organizations can adopt strategies to minimize reliance on workarounds. She provided the following recommendations.

Talk to Staff

Often, workarounds are viewed as violations because the provider is deviating from a policy or process. Ms Graham suggested taking a different approach. “If I were an organization looking at these events, I might not want to look at them from the perspective of what is the clinician doing wrong, but rather ask what is the system or workflow issue that is unsafe or not functioning for the benefit of the patient?”

Organizations should encourage staff to speak up about workarounds. “Frontline staff, more than anyone, may have answers to help fix or make the process better,” noted Ms Graham. To foster information sharing by staff, the organization must promote an open, nonpunitive environment where staff feel at ease talking about workarounds, she said.

Staff may not even be aware that they are using workarounds if the incorrect procedures have become the norm. “Talk about why it’s important to bring workarounds to someone’s attention to improve processes and to ensure patient safety,” advised Ms Graham. Additionally, remind staff to use the organization’s event-reporting system to identify workarounds. “If the organization doesn’t know about them, it cannot investigate them.”

Conduct a Gap Analysis

For processes susceptible to workarounds, “conduct a gap analysis to look at policies and processes as they are scripted, and compare them to what is really occurring,” suggested Ms Graham. The analysis should be multidisciplinary, involving the various stakeholders in the process. “Often, you’ll find that the process doesn’t match workflow,” said Ms Graham. The goal is to understand why the gaps exist and how best to match processes and workflow.

Match Policy and Practice

With any policy or practice, take it for a test run before adopting it. “That may sound obvious, but it’s not always done,” said Ms Graham. By doing a “hands-on walkthrough of the process,” the organization can seek staff input to determine whether the approach is feasible and, if not, what needs to be done to eliminate barriers. When workarounds occur with an already tested policy or process, staff may benefit from additional training. Staff should understand why a practice is in place and how it will improve safety.

Maintain Technology

Given that workarounds can occur with technology, organizations should ensure that an ongoing maintenance plan is in place for the technology to perform reliably. Staff are less likely to resort to workarounds with a well-maintained system.

The organization should also implement a process to conduct periodic reviews of reports provided by a system, such as overrides of dispensing cabinets. The reports can uncover workflow inefficiencies as well as opportunities to reinforce training in important practices.

Additional Patient Safety Focus Areas for Aging Services

Of course, aging services organizations face challenges from many of the other hazards on this list besides workarounds—and many more beyond the scope of the Top 10 report. Below we provide brief guidance on 4 more of the identified 2018 patient safety concerns that have specific relevance for potential harm within aging services provider organizations.

Internal Care Coordination

Poorly coordinated care puts patients at risk for safety events such as medication errors, lack of necessary follow-up care, and diagnostic delays. Like so many preventable errors in health care, these risks come down to a failure to communicate. Providers, including multiple specialists, must inform one another at every step in the care process of the patient’s condition, medication regimen, and medical history.

“Many handoff tools are available to ensure that vital information is communicated and the process is standardized,” said Elizabeth A Drozd, MS, MT (ASCP) SBB, CPPS, senior patient safety analyst, ECRI Institute.

Additional tools such as checklists and safety huddles can help ensure providers communicate effectively at every stage of the patient’s care. Communication training and leadership support are also essential. Whenever multiple providers and specialists are responsible for a patient’s treatment, care coordination will continue to be an issue that must be addressed.

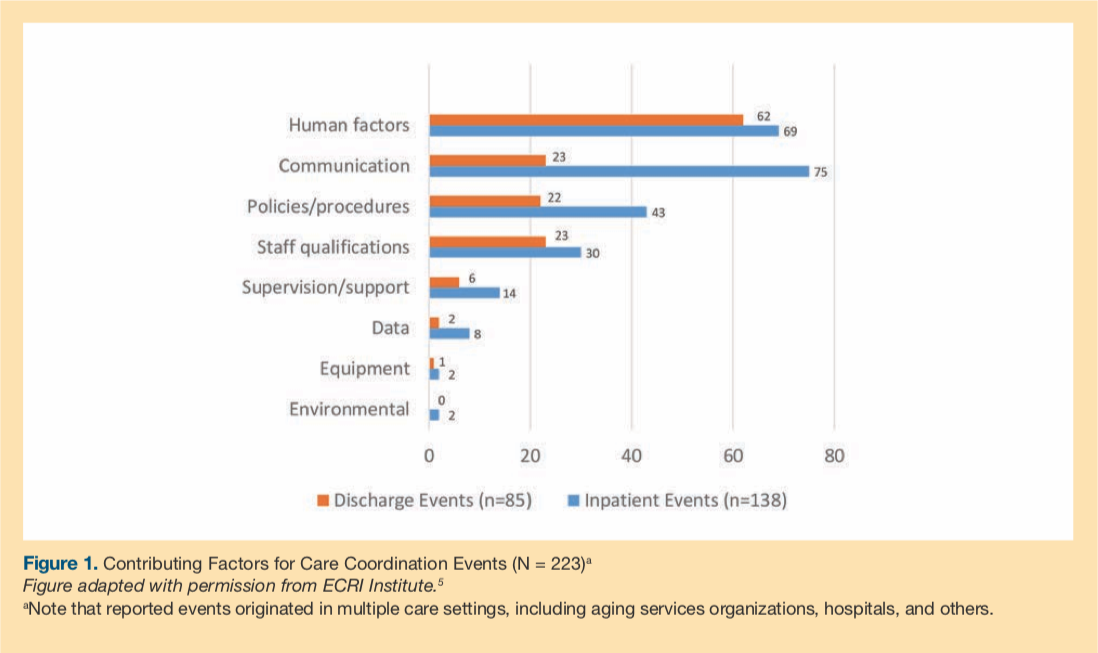

In ECRI Institute PSO Deep Dive: Care Coordination,5 ECRI Institute PSO examined contributing factors to more than 220 care coordination events (Figure 1).

Incorporating Health IT Into Patient Safety Programs

A health information technology (IT) safety program can play a pivotal role in improving the safety and quality of health care, but its success depends on the ability of users to recognize, react to, and report health-IT-related events for analysis and action. If staff fail to recognize health IT issues when they emerge, then they may not know how to intervene.

When health IT systems are poorly designed or when the organization’s culture fails to embrace health IT safety, patients can suffer. “It is not only how we use it in daily workflow, but also how we use it effectively by optimizing the benefits and reducing the risks,” said Robert C Giannini, NHA, CHTS-IM/CP, patient safety analyst and consultant, ECRI Institute.

Facilities should focus on integrating health IT safety into the existing safety program, collaborating with stakeholders, and embedding health IT safety into the organization’s culture.

All-Hazards Emergency Preparedness

The year 2017 saw major hurricanes, wildfires, mass shootings, and ransomware attacks. Each of these emergencies brought a host of challenges for health care facilities. Some resulted in mass casualties; others led to power outages or computer shutdowns, which forced organizations to alter their day-to-day operations. Facilities that were prepared for these disasters fared better than those that were not.

“I don’t know that there’s any way to prevent any future natural disasters, or even most intentional disasters,” said Patricia Neumann, MS, RN, MT (ASCP), HEM, senior patient safety analyst/consultant, ECRI Institute. “Obviously preparing is a whole lot better than having to recover.”

Leadership Engagement in Patient Safety

Leadership engagement in patient safety efforts is essential to their success. Engagement of leadership must be on both an intellectual and an emotional level. “The c-suite and the board, as a result of your persuasion, have to be willing to listen to what you’re saying,” explained Carol Clark, BSN, RN, MJ, patient safety analyst, ECRI Institute. “It all starts with emotional and intellectual engagement.” Without leadership investment, options for patient safety initiatives are limited.

To build support, the patient safety, risk, or quality manager should recruit champions across the organization who can support the cause both up and down the chain of leadership. Then, once the risk manager has achieved champion buy-in, “you have to take this with your champions to the c-suite and board of trustees. You have to engage them intellectually and emotionally. You present crisp, on-target data that demonstrate the need,” said Ms Clark.

Conclusion

Armed with this list, leaders can begin discussions about their own organizations’ safety risks and opportunities for improvements. Beyond the hazards and concerns listed here, this discussion should identify other, organization- or location-specific concerns that leaders may not have raised otherwise.

As a next step, risk managers and other administrators should investigate whether and to what extent these problems are occurring in their own organizations and whether systems and processes are in place to address them. The strategies listed here are a starting point for putting in place broader quality assurance and performance improvement programs that can make care safer.

To download the full Executive Brief, go to www.ecri.org/PatientSafetyTop10.

References

1. Transforming into a high reliability organization in health care. Modern Healthcare website. https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20170727/SPONSORED/170729919. Accessed March 20, 2018.

2. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Patient Safety Network (PSnet). Patient safety primer, high reliability. PSnet website. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/31/high-reliability. Updated November 2017. Accessed March 20, 2018.

3. ECRI Institute. Top 10 patient safety concerns for healthcare organizations: 2018. ECRI Institute website. https://www.ecri.org/PatientSafetyTop10. Published March 12, 2018. Accessed March 20, 2018.

4. Tucker AL. Workarounds and resiliency on the front lines of health care. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Patient Safety Network (PSnet). PSnet website. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/perspectives/perspective/78/workarounds-and-resiliency-on-the-front-lines-of-health-care. Published August 2009. Accessed March 20, 2018.

5. ECRI Institute PSO. Care Coordination: Executive Summary. ECRI Institute website. https://www.ecri.org/EmailResources/PSRQ/PSO/Deep%20Dive%20Exec%20Summary%202015_final.pdf. Published September 2015. Accessed March 20, 2018.

To read more ALTC expert commentary and news, visit the homepage