“There’s a Monster Under My Bed”: Hearing Aids and Dementia in Long-Term Care Settings

Sensory deficits in patients with dementia decrease their quality of life, increase their risk of delirium and falls, and pose a higher risk of poor outcomes. In nursing home settings, evaluation and management of patients with dual disabilities of cognition and sensory impairments poses a challenge due to multiple barriers. The authors report the case of a legally blind and severely hearing-impaired elderly nursing home resident with Alzheimer’s disease who became agitated, confused, and reported having been assaulted. A thorough investigation revealed that her hearing aid was not functioning properly. Once this was addressed, her confusion resolved until another issue with her hearing aid occurred. After this issue was remedied and her care plan was fine-tuned to prevent subsequent problems, no other episodes of agitation and confusion occurred. This clinical experience report shows that sensory deprivation can lead to agitated delirium in patients with dementia and demonstrates the diagnostic value of exploring the nature of specific hallucinations in these persons. It also reviews the barriers to appropriate care for long-term care residents with hearing aids and emphasizes the importance of clinical interventions that address sensory deficits in patients with dementia, such as routine hearing screenings and assessments of listening devices for persons with hearing impairments.

Key words: Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, delirium, hallucinations, hearing aids, hearing screenings, sensory deficits.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Hearing loss has been reported to be the third most prevalent chronic condition in older adults.1 Studies have shown that between 25% and 40% of individuals aged 65 years or older are hearing impaired2-4 and that the prevalence increases with age.5-7 The impact of hearing loss is considerable, as this condition may lead to social isolation, poor self-esteem, and functional disability.8,9 Hearing aids are often prescribed to improve hearing deficits, but compliance with their use has traditionally not been very encouraging.1 Economic and social factors have been reported to be important determinants of regular hearing aid use; however, because poor cognition is a recognized barrier to evaluation of common and treatable problems like hearing impairment, it may prevent hearing aids from even being prescribed.10

Evaluation of cognitively impaired elderly persons in ambulatory settings is challenging, but this task becomes even more difficult when accompanied by hearing impairment. When cognitively impaired persons with sensory deficits are encountered in long-term care (LTC) facilities, the challenges of evaluation are amplified due to the high prevalence of advanced cognitive impairment and other comorbidities in this population, leading to a high incidence of behavioral issues, delirium, depression, and falls. In addition, standard practice tools for hearing assessments, such as the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE),11 are rendered less practical and more difficult to validate in cognitively impaired elders.

Because hearing-related problems have far reaching psychosocial, economic, and functional implications on elders’ wellbeing,8,9,12-14 a focused screening strategy for identification of treatable hearing conditions may help these individuals maintain their cognitive and functional status.15,16 The challenging task of screening for hearing impairment and testing for hearing aid malfunction in the presence of a multitude of barriers requires a focused, targeted assessment. A basic knowledge of common hearing aids, how they function, and strategies for troubleshooting issues can prove invaluable when assessing elders with hearing problems, particularly those with cognitive impairments. In this article, we provide an overview of these issues, but first present a case scenario that puts them in context.

Case Scenario

We evaluated a 91-year-old black woman for an incident of agitated behavior, which she stated resulted from having been sexually assaulted the night before. The patient resided in the nursing home for the past 4 months, but had been living in a wing for cognitively impaired residents for the past 2 months. She was dependent in her activities of daily living and had a history of falls. The patient’s medical history included osteoarthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, glaucoma, hemorrhoids, degenerative arthritis of the spine, legal blindness, prolapsed bladder, recurrent urinary tract infections, and a severe hearing impairment. She wore a hearing aid in her left ear, as hearing from her right ear was completely lost many years earlier. She also had an indwelling catheter for her prolapsed bladder, but her family contemplated having a suprapubic catheter placed to improve her quality of life. The patient’s medications included acetaminophen 500 mg twice daily, aspirin 81 mg daily, dorzolamide hydrochloride eye drops once daily, and a stool softener once daily.

In consulting with the patient’s family regarding her report of sexual assault, they noted that she had made such claims before, likely due to her probable history of being a rape victim, and noted that her agitation may have stemmed from the anxiety over her move to the new wing of the facility. A thorough investigation of the incident was undertaken, which included a hospital visit and an examination for assault. Staff interviews revealed that she had intermittent bouts of confusion, particularly at night, over the week that preceded her accusation of sexual assault. During these episodes, the staff noted that she yanked on her catheter and yelled, “Why are you doing this to me?” They also reported that she did not listen to them during these events and that her behavior was not redirectable, but that she was eventually consoled after being brought to the nursing desk in her wheelchair. The interview with the patient was inconclusive because of her inability to recall the incident. In addition, she was unable to answer questions until spoken to in a well-lit area with the speaker’s face very close to her eyes, enabling her to read lips. When spoken to in this manner, however, she demonstrated the ability to follow simple commands and could verbalize her concerns.

Records showed that she was compliant with all of her medications on the night of the event, no falls or disruption in bowel function were reported, and no signs of pain were observed. Her vital signs were normal and she was pleasant and cooperative during the clinical assessment. A urinalysis, basic metabolic panel, and complete blood count were normal. None of the physical examination findings changed from her previous examination. The patient’s vision was very limited. She had poor color perception and was only capable of seeing shadows and outlines in bright light. A Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) could not be performed due to her limited attention span and sensory deficits, but her most recent score was noted to be 12 out of 30. A hearing assessment was conducted.

Hearing Assessment and Interventions

To test if her hearing aid was functioning properly, a 512-Hz tuning fork was struck against the palm of the hand and held from 1 inch up to 12 inches away from her left ear. She was only able to hear the vibrations from the tuning fork at the onset of the vibrations when it was held at a distance of up to 3 inches from her left ear. After repeated testing to confirm the audible distance, the hearing aid was removed. During removal, no whistling or beeping was heard (these sounds are often heard during the process of wearing or removing a hearing aid), indicating a depleted battery. An examination of the patient’s ear canal and eardrum showed no abnormalities. The tuning fork was used again in a similar fashion to assess the patient’s hearing without the hearing aid in place. Her hearing remained unchanged, with audible vibration reported at 3 inches, confirming that the hearing aid was not functioning.

After the battery in the patient’s hearing aid was replaced, she could hear the vibrations from the tuning fork at a distance of approximately 12 inches from her left ear, and her bouts of agitation and confusion resolved. The patient’s care plan was reviewed with her family and the following new measures were implemented: (1) keep her room well lit during the night; (2) have her family replace her hearing aid batteries on a regular basis; and (3) make an appointment with a urologist to have her indwelling catheter replaced with a suprapubic catheter to reduce her discomfort and the risk of infection.

(Continued on next page)

Recurrence Evaluation and Management

Eight weeks later, the patient started to experience visual hallucinations again at night. The nursing staff reported that she became agitated during these episodes and yelled, “There is a monster or man under my bed.” During these events, the patient was consoled by the presence of a caregiver or by being close to the nursing desk. She also responded to an additional dose of lorazepam. Her daughter was contacted about the incident, and she demanded that something be done immediately.

A clinical assessment was undertaken, which was normal. The patient was pleasant but seemed slightly anxious. Poor vision and hearing were noted. She was only able to recognize the presence of persons when they were in very close proximity to her face, and she could only follow commands and answer questions when they were spoken directly into her left ear, despite the hearing aid being in place. When the hearing device was removed from her left ear, no whistling or beeping noises were audible. The patient’s ability to hear spoken words remained unchanged after removal of the device. Her ear examination was normal. These findings indicated a problem with the hearing aid’s battery. Her family reported that the battery had been changed 3 weeks earlier. After the battery was replaced and testing was repeated with the tuning fork, she was able to hear the vibrations at onset from a distance of approximately 12 inches while wearing her hearing aid, and from 3 inches without her hearing aid. The battery change had promptly restored her hearing to her baseline level.

Further discussions with the patient’s family revealed that the scheduled battery change, which was usually done by her daughter, did not occur as had been previously stated. In addition, an inspection of her room revealed that the light in her bathroom that was being kept on at night to illuminate the room was casting shadows capable of causing illusionary perception, particularly in persons with sensory impairments. Based on these findings, the patient’s care plan was fine-tuned as follows: (1) the light in her room was adjusted to improve sensory perception while avoiding shadows being cast at night; (2) her hearing aid battery was scheduled to be changed promptly every third week to prevent any further episodes of sensory deprivation; and (3) regular follow-up by the care team was scheduled to ensure compliance with the care plan.

A family meeting was arranged to review the care plan and discuss the interventions, which were successfully implemented. On follow-up examinations, no further episodes of agitation and visual hallucinations were reported. The sensory ambiance in the patient’s room continues to be monitored and her hearing aid batteries are being replaced as scheduled.

Discussion

Nearly one-third of all nursing home residents have difficulty seeing or hearing, 46% have some form of dementia, and 30% to 84% of residents with dementia show some form of agitation.17 Our case report highlights a rather unique scenario, demonstrating how cognitive impairment in combination with profound sensory deficits, particularly hearing impairment, can lead to agitation. In the medical literature, agitation has been reported as a symptom of an unmet medical need or psychiatric distress in cognitively impaired elders.18,19 One study that examined the unmet needs of LTC residents with dementia found that their needs were often unmet with regard to their vision and hearing problems.20 There are a variety of reasons for why vision and hearing needs may go unmet, as clinicians face many barriers to identifying and treating these problems in the LTC setting; however, they should make every effort to overcome these barriers, as nursing home residents who do not receive appropriate care for these issues may experience social isolation, cognitive decline, decreased mobility, and numerous other problems.8,9,12-14

In a 2006 review by Cohen-Mansfield and Infeld,21 which examined the use of hearing aids in nursing homes and the financial coverage available for these devices, the authors reported that a major barrier to their use is the cost of the equipment. They report that cost has led to sparse use of hearing aids in the nursing home population, and they note that there is a need for future policy development to improve both the quality of hearing aids and the financial mechanisms that would enable nursing home residents to use them. However, it has been shown that even when financial barriers are overcome, compliance with use of hearing aids is poor among elders.1 Compliance issues are likely exacerbated in cognitively impaired nursing homes residents, as there are additional barriers to contend with in this patient group.

Although there is ample literature stressing the importance of screening for hearing impairment in elderly nursing home residents, we could find no formal position statement or clinical protocol in the medical literature outlining assessment and treatment measures for this population, particularly those with cognitive impairment and agitation, behavioral issues, and falls. We used a tuning fork to evaluate our patient’s hearing. Although tuning forks are not traditionally used for hearing assessments, they can be useful for clinical scenarios that require an innovative clinical approach. We found some supporting evidence for this approach in a study by Uhlmann and colleagues,22 which examined the reliability of hearing tests in demented versus nondemented patients. The authors found that use of a 512-Hz tuning fork, finger rub test (ie, fingers are rubbed together), and whispered voice test performed well as auditory screening tools in patients with dementia, demonstrating high sensitivities and specificities.In another study,23 the whispered voice test was found to be a good screening tool to determine whether additional hearing screening, such as with a tuning fork, is required.23 What follows is some information on conducting hearing assessments with a tuning fork, which can be a quick and reliable way to determine hearing status when an impairment is suspected. We also review hearing aid types and battery life, which are important considerations for cognitively impaired persons, as they are less likely to be able to communicate problems with their hearing aid, such as a depleted battery. Finally, we outline methods for troubleshooting commonly encountered hearing aid problems that may lead to noncompliance, such as sounds that come and go.

(Continued on next page)

Performing a Tuning Fork Test

Hearing tests can be performed numerous ways with tuning forks, including the Rinne, Weber, Bing, and Schwabach methods; however, these have limitations and are too complex to use in cognitively impaired adults, as they often require more detailed feedback than these patient are capable of giving. Based on our experience, we think that the best method is also the simplest. We advocate having the examiner hold the tuning fork firmly by its stem and striking the tines lightly (to prevent overtones) against the heel of his or her hand, moving the tuning fork briefly next to his or her own ear to ensure it was properly struck, and then placing the tuning fork 1 inch from the patient’s external auditory canal, from which it is then withdrawn at a rate of 1 foot per second. The patient is instructed to report when he or she can no longer discern the tone, which is a task most patients with mild to moderate cognitive impairment are capable of.

Tuning forks come in different frequencies. When used for hearing assessments, frequencies of 256 to 1024 Hz have been employed; however, higher pitched forks, such as the 512-Hz fork, are generally recommended.24 If a tuning fork is not accessible, clinicians can consider performing the finger rub test or the watch tick test at 6 inches from the ear, which have been shown to accurately detect hearing loss greater than 25 dB.25 Although these tests have demonstrated efficacy, we recommend using a tuning fork whenever possible, as the sound emitted from a tuning fork is more consistent compared with rubbing of the fingers or the tick of someone’s analog watch.

Hearing Aid Types and Battery Life

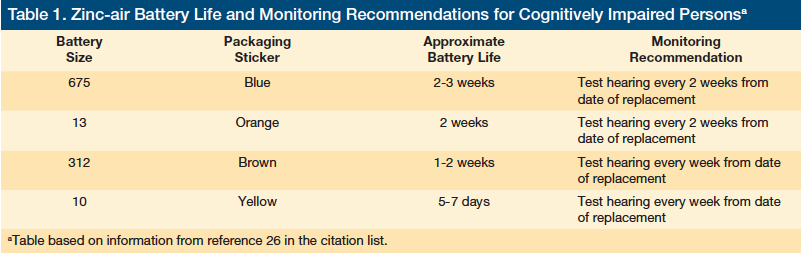

The average life of a digital hearing aid is about 5 years, but the battery life of these devices is variable. As with other appliances, numerous factors impact the battery life of hearing aids, including usage time, complexity of functions (eg, programmability), battery type and size, and degree of hearing loss.26 Zinc-air batteries, which are not rechargeable, are the most commonly used batteries for hearing aids. These batteries come in four main sizes: 675, 13, 312, and 10 (Table 1). With average use, a size 675 battery lasts 2 to 3 weeks, a size 13 battery lasts 2 weeks, a size 312 battery lasts 1 to 2 weeks, and a size 10 battery lasts 5 to 7 days; battery longevity is indicated by a colored sticker on the packaging.26 Because numerous factors can shorten the lifespan of these batteries, as previously noted, batteries should be routinely checked. Although some people think that a battery tester can be used to monitor the strength of zinc-air batteries, these testers can only show when these batteries have been depleted.27 Therefore, healthcare providers will have to test hearing, rather than the battery itself, to determine if a battery replacement is necessary. To ensure that such monitoring does not get overlooked, nursing homes should consider implementing a battery change policy for each of their residents with hearing aids to ensure that these individuals have functional devices.

Several hearing aid models are available that accept nickel-metal hydride (NiMH) batteries, which are rechargeable batteries that are designed to replace zinc-air batteries. NiMH batteries require a charger, and various options are available, including portable varieties. Depending on the charger used, charging time ranges from around 2.5 hours to 5 hours.28 According to the manufacturers, these batteries can be charged as many as 600 times.28 While rechargeable batteries may seem preferable to nonrechargeable varieties, they are not practical for patients with cognitive impairment because adequate maintenance demands daily charging and battery changes.

Extended-wear disposable hearing aids, which require no battery changes, are available. These hearing aids can last from 90 to 120 days, but they are not widely used. Disposable hearing aids are preprogrammed in the factory and are designed using a one-size-fits-all approach; thus, they cannot be adjusted or reprogrammed for a custom fit. Use of disposable hearing device should be determined based upon each individual’s unique clinical scenario and demands; however, they are likely best reserved for patients with minimal cognitive impairment who have mild to moderate hearing loss, are aware of their hearing deficit, and are likely to be compliant with using their hearing aid.

Troubleshooting Hearing Aid Problems

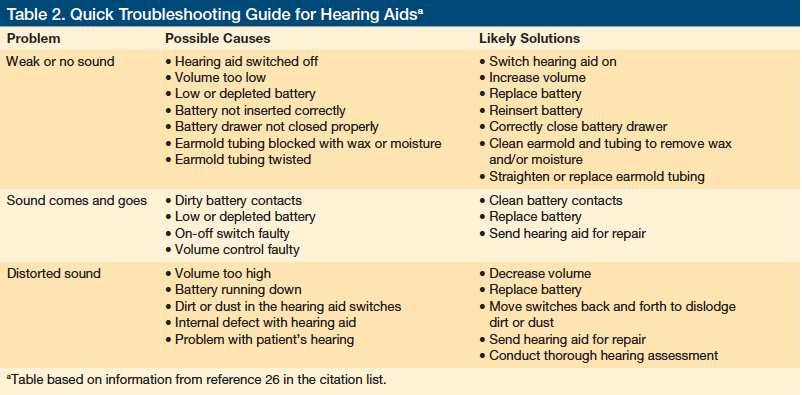

Several common problems are associated with hearing aids, including weak or no sound, sound that comes and goes, and distorted sound. All of these issues can be frustrating for elders and can lead to noncompliance with hearing aid use. The good news is that these problems are both avoidable and easily resolved when caregivers understand the basic functioning of hearing aids (Table 2).

When the problem is weak or no sound, caregivers should check to see if the hearing aid is switched off, set to a low volume, has working batteries, has incorrectly inserted batteries, or has an improperly closed battery drawer. If none of these are found to be the cause, the earmold tubing could be twisted or blocked from moisture or earwax, making the device nonfunctional. These issues can be remedied by straightening or replacing the tubing and removing the earwax from the earmold. A pipe cleaner can be used to remove moisture from the tubing, and the battery door can be opened at night to dry out any additional moisture in the device.29

If the sound comes and goes, the battery contacts may be dirty, the battery may be depleting, or the on-off switch or volume controls may be faulty. In these cases, repair may be required. With regard to issues of distorted sounds, caregivers should check to see if the volume is turned up too high, if the battery is drained, or if there is any dirt in the hearing aid switches. For the latter issue, moving the switches back and forth can dislodge any grime. If this does not work, the patient may need to have another hearing assessment, as their hearing may have worsened. An internal defect with the hearing aid is also possible, and repair or replacement may be warranted. Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for a defect when the hearing aid is 5 years old or older, as that is the general life expectancy of these devices.

In general, caregivers should routinely replace hearing aid batteries and check that they are installed properly, particularly for patients with cognitive impairment, as these patients may not be able to communicate that they are experiencing any issues with their hearing aid. Taking such proactive measures can both improve compliance and prevent confusion and agitation, as occurred with our patient.

Another important measure to take is to ensure that LTC patients with cognitive deficits do not lose or misplace their hearing aids, as this is another commonly encountered problem. To avoid such incidents, staff at LTC facilities should account for the location of each hearing aid at night. In addition, a tether attached to the hearing aid with the other end pinned to clothing is an option for individuals who are prone to removing their hearing aids during the day.

Conclusion

Hearing impairments in patients with dementia can cause significant psychosocial distress and poor health outcomes. Although it is important to screen these patients for hearing impairment, this can be a particularly challenging endeavor. The paucity of evidence-based clinical strategies and tools focusing on the cognitively impaired patient with hearing impairment underscores this problem. We recommend routine screening for both hearing impairments and hearing aid functionality in nursing home residents, making these measures a part of the care plan of all patients. Increasing awareness among staff and family members about hearing impairment and its related behavioral manifestations if left untreated can also help these problems be quickly identified and corrected.

(Continues on next page)

References

1. Yueh B, Shapiro N, MacLean CH, Shekelle PG. Screening and management of adult hearing loss in primary care: scientific review. JAMA. 2003;289(15):1976-1985.

2. US Department of Commerce. Statistical Abstract of the United States. 117th ed. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 1997.

3. Gates GA, Cooper JC Jr, Kannel WB, Miller NJ. Hearing in the elderly: the Framingham cohort, 1983-1985; part I: basic audiometric test results. Ear Hear. 1990;11(4):247-256.

4. Rueben DB, Walsh K, Moore AA, Damesyn M, Greendale GA. Hearing loss in community-dwelling older persons: national prevalence data and identification using simple questions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(8):1008-1011.

5. Parving A, Philip B. Use and benefit of hearing aids in the tenth decade and beyond. Audiology. 1991;30(2):61-69.

6. Rahko T, Kallio V, Kataja M, Fagerstrom K, Karma P. Prevalence of handicapping hearing loss in an aging population. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1985;94(2 pt 1):140-144.

7. Ciurlia-Guy E, Cashman M, Lewsen B. Identifying hearing loss and hearing handicap among chronic care elderly people. Gerontologist. 1993;33(5):644-649.

8. Kay DW, Roth M, Beamish P. Old age mental disorders in Newcastle upon Tyne; II: a study of possible social and medical causes. Br J Psychol. 1964; 110:668-682.

9. Herbst KG, Humphrey C. Hearing impairment and mental state in the elderly living at home. BMJ. 1980;281:903-905.

10. Elsawy B, Higgins KE. The geriatric assessment. Am Fam Physician. 2011; 83(1):48-56.

11. Ventry IM, Weinstein BE. The hearing handicap inventory for the elderly: a new tool. Ear Hear. 1982;3(3):128-134.

12. Carabellese C, Appollonio I, Rozzini R, et al. Sensory impairment and quality of life in a community elderly population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(4):401-407.

13. Appollonio I, Carabellese C, Frattola L, Trabucchi M. Effects of sensory aids on the quality of life and mortality of elderly people: a multivariate analysis. Age Ageing. 1996;25(2):89-96.

14. Mulrow CD, Aguilar C, Endicott JE, et al. Association between hearing impairment and the quality of life of elderly individuals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(1):45-50.

15. US Department of Health and Human Services, US Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics. Healthy People 2000 Review, 1995-96. Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics; 1997.

16. Kochkin S, MarkeTrak IV. What is the viable market for hearing aids? Hearing J. 1997;50:31-39.

17. Burkhalter CL, Allen RS, Skaar DC, Crittenden J, Burgio LD. Examining the effectiveness of traditional audiological assessments for nursing home residents with dementia-related behaviors. J Am Acad Audiol. 2009;20(9):529-538.

18. Cohen-Mansfield J, Billig N, Lipson S, Rosenthal AS, Pawlson LG. Medical correlates of agitation in nursing home residents. Gerontology. 1990;36(3):150-158.

19. Ishii S, Streim JE, Saliba D. Potentially reversible resident factors associated with rejection of care behaviors. Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(9):1693-1700.

20. Orrell M, Hancock GA, Liyanage KC, Woods B, Challis D, Hoe J. The needs of people with dementia in care homes: the perspectives of users, staff and family caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20(5):941-951.

21. Cohen-Mansfield J, Infeld DL. Hearing aids for nursing home residents: current policy and future needs. Health Policy. 2006;79(1):49-56.

22. Uhlmann RF, Rees TS, Psaty BM, Duckert LG. Validity and reliability of auditory screening tests in demented and non-demented older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(2):90-96.

23. Bagai A, Thavendiranathan P, Detsky AS. Does this patient have hearing impairment? JAMA. 2006;295(4):416-428.

24. Hain TC. Hearing testing. www.dizziness-and-balance.com/testing/hearing/hearing_test.htm. Modified December 13, 2011. Accessed July 26, 2012.

25. Boatman DF, Miglioretti DL, Eberwein C, Alidoost M, Reich SG. How accurate are bedside hearing tests? Neurology. 2007;68(16):1311-1314.

26. Cleveland Hearing & Speech Center. Be a savvy shopper. Tips for success when buying hearing aids. https://bit.ly/Q6a8mo. Accessed July 30, 2012.

27. Du Brey L. What hearing instrument users need to know about their batteries. www.hearingoffice.com/download/BatteryFAQ.pdf. Updated December 8, 2009. Accessed July 26, 2012.

28. Microbattery.com. Rechargeable batteries & chargers. https://shopping.micro

battery.com/Rechargeable-Hearing-Aid-Batteries-Chargers. Accessed July 30, 2012.

29. Family Support Connection. Troubleshooting your hearing aid. www.familysupportconnection.org/html/HATroubleshoot2.htm. Accessed July 30, 2012.

Disclosures:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to:

Raza Haque, MD

B111 w Clinical Center

East Lansing, MI 48824-1313

raza.haque@hc.msu.edu