Therapeutic Benefits of Implementing an Aging Film Series in a Long-Term Care Facility

Inspired by calls for culture change in long-term care (LTC) and by traditional self-management approaches to health (eg, bibliotherapy), the authors conducted a pilot study aimed at improving resident quality of life and staff morale on an inpatient geriatric rehabilitation unit. Feasibility of an innovative program to host monthly film showings was tested in the community living center (CLC) of the Oklahoma City VA Medical Center. In an attempt to stimulate reflection and reduce feelings of isolation, the authors joined residents and their providers in viewing films encapsulating health-related aspects of the aging process and discussing them in an environment of informal interaction and camaraderie. The program appeared to enhance resident-directed care and quality of life by stimulating empathy and fostering a therapeutic sense of community. The film series was cited as evidence of cultural transformation during an independent evaluation of quality improvement and compliance review at the center. This program may be easily modified to fit other LTC environments serving older adults.

Key words: behavioral health, psychosocial medicine, patient self-management, cultural transformation, quality improvement, quality of life

Abstract: Inspired by calls for culture change in long-term care (LTC) and by traditional self-management approaches to health (eg, bibliotherapy), the authors conducted a pilot study aimed at improving resident quality of life and staff morale on an inpatient geriatric rehabilitation unit. Feasibility of an innovative program to host monthly film showings was tested in the community living center (CLC) of the Oklahoma City VA Medical Center. In an attempt to stimulate reflection and reduce feelings of isolation, the authors joined residents and their providers in viewing films encapsulating health-related aspects of the aging process and discussing them in an environment of informal interaction and camaraderie. The program appeared to enhance resident-directed care and quality of life by stimulating empathy and fostering a therapeutic sense of community. The film series was cited as evidence of cultural transformation during an independent evaluation of quality improvement and compliance review at the center. This program may be easily modified to fit other LTC environments serving older adults.

Key words: behavioral health, psychosocial medicine, patient self-management, cultural transformation, quality improvement, quality of life

Citation: Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging. 2015;23(8):33-39.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

For decades, physicians have highlighted the importance of meeting the psychosocial needs of older patients in long-term care (LTC).1-4 However, the extent to which these and other non-biomedical needs are routinely met within geriatric care remains unclear and varies by institution.5 This issue could not be more timely, as the nation’s life expectancy and incidence of chronic illness continue to grow,6 the supply of geriatricians diminishes, an emphasis on inter-professional collaboration and team-based care is renewed, and the healthcare system becomes predominantly private with services being guided by cost containment.

It has been well documented that older adults have an increased risk for nursing home admission or death following acute hospital stays, yet tailored geriatric rehabilitation services are not standard practice.7 Limited resources must be balanced with the increased demand for care. Well-publicized concerns about LTC environments, such as skilled nursing facilities and rehabilitation units, often focus on staffing challenges, citing low morale and high turnover, especially among nurses and nurse aides.8 These concerns are particularly important since staff-patient relationships have long been a cornerstone of evaluating and determining quality of care.9,10 Following a 2001 report on LTC quality by the Institute of Medicine, studies evaluating interventions targeting residents’ psychological health and quality of life11,12 have called for a change in LTC culture that emphasizes coordinated, team-based communication13 and a person-directed rather than institutional approach.14,15

Effective disease self-management, an increasingly popular concept, can enhance life quality by increasing patients’ sense of independence. Patients may feel empowered by control of their own care, which, with appropriate support, can provide the necessary motivation to engage and persist in health-promoting behavior. As demonstrated by the robust literature supporting self-efficacy, when patients experience success at managing their own health, their confidence in continuing such behavior is enhanced, and a “feedback loop” ensues, resulting in consistent, beneficial health outcomes.16–26

Bibliotherapy, the therapeutic use of books or literature, is one self-management modality shown to enhance skills of daily living, including problem-solving and communication.32 First described in The Atlantic Monthly nearly a century ago,33 this “self-help” approach has also been effective in reducing substance use34 and, in some studies, depression and anxiety, although the results regarding the latter conditions have been mixed.35-40 Although cost-effective, traditional bibliotherapy does require a level of cognitive function and literacy that some older patients (eg, those recovering from acute medical events, living with mild visual and/or cognitive impairment, or limited in formal education) may not possess. In contrast, film is a more universally accessible option that may offer similar benefits to books or literature for disease self-management.

Implementation of the Aging Film Series

Globally, film is a common source of entertainment, but little is known about its therapeutic utility. Movies are enjoyable for multiple reasons, including the ability to identify and empathize with characters and storylines as well as the opportunity to “escape” that is inherent to the cinematic experience. Awareness of a film’s fictitious quality, a priori, allows people to conceptualize movie-viewing as an opportunity to shift focus and “tune out” everyday life, at least briefly. This respite may be therapeutic in itself, but in some cases, the film’s impact may endure. What’s more, by enabling viewers to empathize and perceive commonalities with characters and storylines, feelings of isolation are diminished.

To investigate the potential therapeutic value of film, the Aging Film Series was introduced with a heterogeneous group of older veterans receiving care in the community living center (CLC) of the Oklahoma City VA Medical Center. Consistent with the VA’s national priorities of person-directed care and cultural transformation, the series was designed to provide an informal forum where residents and staff could address aging-specific challenges and model various coping strategies. This research protocol was deemed a quality improvement intervention by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center.

Setting

The CLC is a “short-stay” integrated care unit providing time-limited rehabilitative services to veterans who have deconditioned as a result of surgery or medical event. The center has 21 beds, and the average length of stay is 28 days. The inter-professional staff includes nurses, geriatricians, psychologists, social workers, rehabilitation specialists, nutritionists, and a consulting psychiatrist. Utilization of this interdisciplinary team ensures a holistic approach to care, especially important for older patients who often face multimorbidity41 that includes both physical and mental health conditions.41,42 From admission to discharge, resident progress is continually monitored and evaluated, functional ability and quality of life are prioritized, and independence is fostered whenever possible. In the CLC, as in most rehabilitation settings, there are several logistical challenges to addressing the psychosocial impact of medical illness. Many residents must share their living space with a roommate, a curtain acting as the only partition between the two. This limits privacy and complicates formal counseling opportunities. Designated timeframes where resident concentration can be sustained and interruption minimized are generally unclear and unpredictable; ongoing monitoring and frequent visits by multiple providers are often unannounced; medications are administered; blood glucose levels are checked; vital signs are recorded; and pain is assessed throughout the day. As a result, opportunities to engage residents more deeply, particularly regarding behavioral and emotional aspects of illness, require extensive planning and flexibility.

Film Selection and Showings

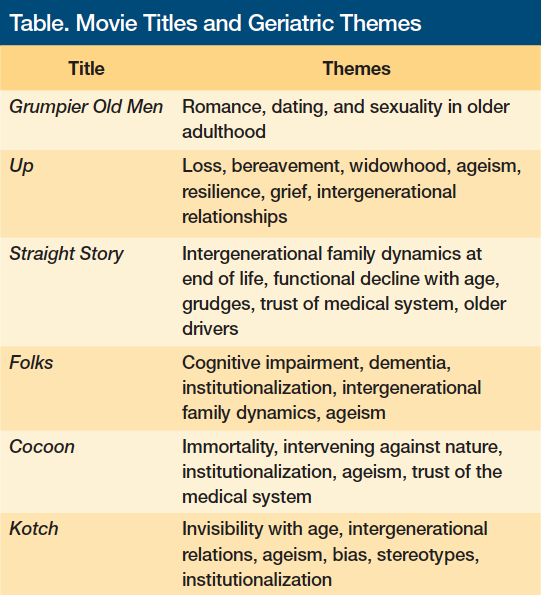

The idea for a film series was first introduced to residents at a CLC resident council meeting, during which residents were provided the opportunity to discuss and plan unit programming and express their care preferences. The monthly meeting’s goal was to create a sense of community and allow residents to maximally shape their rehabilitation environment. Residents expressed a preference for comedy and Western films. War-related material was to be avoided, an understandable preference given the prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder within this population.43 Resident feedback was shared with providers from different disciplines (ie, geriatric medicine, occupational therapy, geropsychology), and a consensus emerged that a monthly series was most feasible. All films addressed themes relevant to older adulthood and were selected based on resident and provider input (Table).

Each month, a film showing was scheduled from 3:00 pm to 5:00 pm, generally on a Friday. This time slot was chosen for two reasons. First, providers’ schedules were often more flexible on Friday afternoons, so this facilitated provider attendance. As providers and residents viewed films together, focus on illness was deemphasized in favor of informal interaction. Portable devices were utilized to measure blood sugar, subtly, without disrupting the viewing experience. Second, late afternoon showtimes allowed film endings to occur just prior to dinner service. The shared viewing experience provided residents instant conversation material for group reflection and discussion during their meal.

To accommodate substantial variability in resident mobility, films were advertised to begin at 2:30 pm, allowing residents time to ambulate to the dining room where the showings occurred. Films were shown on a large-screen TV in the dining area to maximize comfort and convenience for those with limited mobility. Popcorn and beverages were served upon request. This deinstitutionalized the environment and simulated an actual cinematic experience.

Clinical Observation

BB, a clinical geropsychologist, was present for all films and viewed each in its entirety. As time permitted, SQ, the hospital’s chief of geriatrics, also viewed the films alongside residents and other staff. During each screening, BB positioned himself at an angle where both film and attendees were visible at all times. This allowed for direct observation of resident reactions to the film, their providers, and each other, as well as discrete recording of behavioral data.

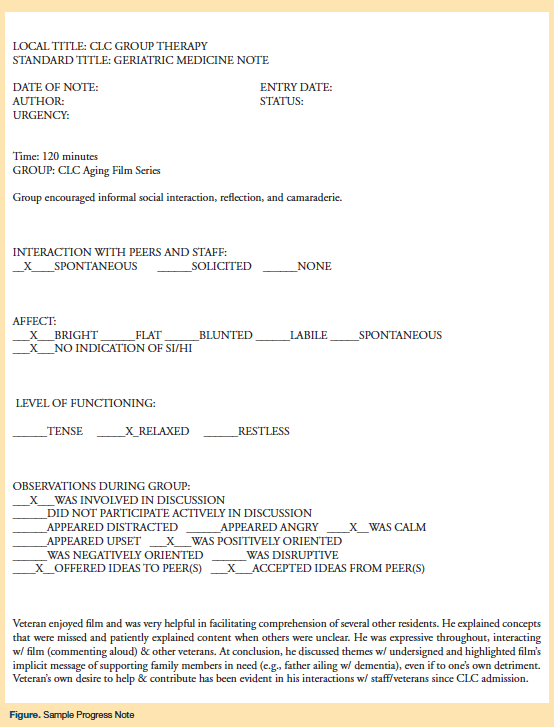

At the conclusion of the film, the authors directly solicited residents’ opinions about the film and engaged in related discussion. This often extended into mealtime conversations. The two authors later debriefed and discussed their own assessment of the film’s impact on residents, and they later transferred their joint observations into group therapy note templates (Figure) to be included in attendees’ electronic medical records.

Resident Feedback

While viewing the films, residents expressed differing responses to the films. Given their military background, many maintained a stoic stance with regard to their health conditions and rehabilitation. Although some movies elicited stronger personal reactions than others, all of the films shown seemed to resonate with those in attendance. Residents frequently communicated and interacted with the characters on screen, uttering reflections out loud such as “that’s for sure” or “ain’t that the truth.” Others had difficulty comprehending the films and relied on their peers for real-time explanations of what was happening. Some displayed unwavering focus on the screen, whereas others were easily distracted or had trouble staying awake.

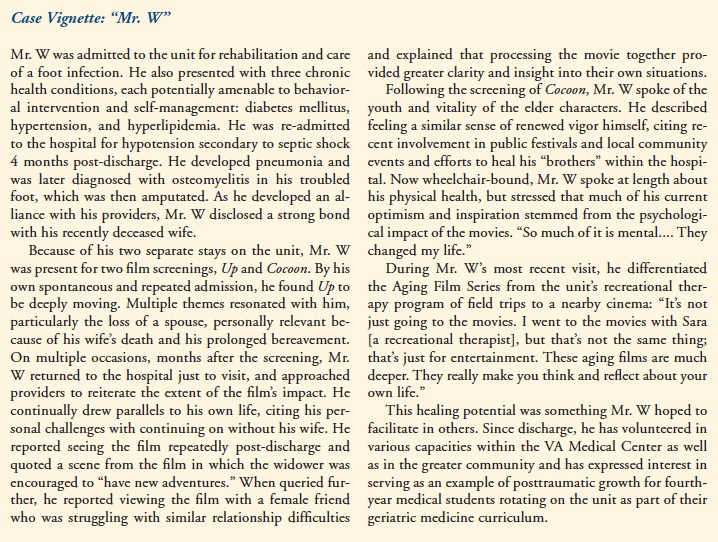

When directly queried about their opinions at film’s end, many veterans remained engaged, commonly responding, “That could’ve been me.” The clearest example of this was the film Up. Though animated, the film offered a vividly detailed depiction of growing old and highlighted a common source of grief among the aged: bereavement. Months after Up was shown, at least two veterans, who were discharged and now receiving outpatient services, continued to reference it as “life-changing.” Like the film’s main character, both residents were widowers, and both cited a particular scene in which the dying wife gave permission for the protagonist to continue enjoying his life, even after she was gone, as having affected them. This message, the residents reported, was applicable to their own situations but difficult to achieve as they faced the life-altering, physical challenge of lower-extremity amputation.

In another instance, a generally quiet and somewhat withdrawn resident who had attended the screening stopped providers to express appreciation for the movie choice. He later disclosed he was related to one of the film’s producers. This interaction quickly evolved into a 30-minute “update” on the resident’s rehabilitation progress and coping ability. In this case, the film opened the door for dialogue and information gathering that may not have otherwise occurred. It also provided an opportunity for enhanced rapport and an outlet for the resident to share with providers his identity as an individual, including deep pride related to his Hollywood connection.

Residents’ ability to identify with film themes was not always pleasant for them. In one example, a film addressing dementia greatly disturbed a resident who had placed his wife, stricken with Alzheimer’s disease, in a nursing home several years prior. The resident expressed his displeasure, and providers followed up the next day to process and debrief further. Though initially unsettling for the resident, the evocative power of the film led him to reveal more specific concerns he had only alluded to previously. After more detailed discussion, he expressed appreciation for getting it “off my chest.” Many examples of similar resident outcomes stood out, including the one described in the Case Vignette.

Discussion

Increased Reflection and Reduced Isolation

Overall, the film series provided a unique and cost-free opportunity for residents and staff to jointly reflect on the health-related impact of aging. Because routine care largely focuses on symptom management, limited time is available for residents to process the experience and implications of their illness. The films—chosen for their evocative potential and aging-themed content and guided by veteran preferences—offered an opportunity for residents and providers to engage with each other and experience the healing power of empathy. Although each resident responded uniquely to the films, most could identify with the aging process, a central and recurring theme in all the films. The perceived commonalities between the movie characters’ circumstances and those of the residents seemed to reduce residents’ feelings of isolation, which is prevalent among older adults and a known risk factor for abuse,44 depression,45 hospital readmissions,46 time spent in LTC,47 and death.48

Although not every veteran reported the same level of impact as Mr. W, his intense and ongoing reaction clearly illustrated film’s capacity to engage, inspire, motivate, and aid recovery. In addition to serving as a springboard for reflection and discussion, the series allowed for clinical observation of resident behaviors that approximated how they might handle similar scenarios upon discharge, thus providing important data about their progress, health status, and capacity for self-management. Fidgeting or agitated eating suggested possible anxiety. Poor comprehension or attention might be due to cognitive impairment, delirium, or sleep difficulty, any of which might signal a need for follow-up evaluation and medication reconciliation. Resident disengagement could indicate affective or mood-related concerns such as depression.

Cultural Transformation

Beyond individual outcomes, the film series aimed to enrich provider experiences and enhance the therapeutic culture of the unit as a whole, especially relevant in light of well-documented challenges related to job satisfaction among LTC staff.49

To this end, SQ made a point of attending all films to the extent possible. His presence left a positive impression on several residents and served as a model to other providers on the team. During these more informal encounters, conversation strayed from illness and moved toward getting to know one another, allowing for everyone present to see that the unit’s chief physician was approachable and interested in residents as people, not merely in their diseases. This subtle yet powerful distinction has become a point of emphasis within medical training.51 Such interactions can build trust, a component linked to effective care for nearly a century51–54 and most directly influenced by physician personality and behavior.55 At the individual level, residents can adopt an identity other than that of patients and occupy a role other than as a dependent, while affording providers an opportunity to demonstrate the nonprofessional sides of their personalities, thereby strengthening the therapeutic relationship.56 By encouraging both resident and provider engagement, with content applicable to all team members and residents, the film series appeared to help shape a healing rehabilitation environment conducive to recovery. In fact, The Long Term Care Institute,57 the agency contracted by the hospital to evaluate and assess quality assurance, review, and measurement, formally identified the series as evidence of cultural transformation—one of two national VA initiatives.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study was that outcomes were measured and recorded solely via resident comments and author observation at one time point (during and immediately following films), without formal follow-up. Therefore, all of the outcomes reported are qualitative. Furthermore, most of the follow-up conversations described here were spontaneously initiated by the residents themselves, and therefore may not be representative of all of the responses residents had to viewing the films. Though more formal outcome assessments are desirable, therapeutic use of film in LTC is rare, and standardized measures do not currently exist.

Future research should include more structured program evaluation and measures of attendee feedback, ideally recorded by audio or video, and followed by an independent process of thematic analysis. Notwithstanding these methodological limitations, staff and resident feedback suggest the Aging Film Series provided benefit to both and merits further investigation.

Conclusions

Continued growth of the geriatric patient population and shifts from acute to chronic illness will certainly increase the need for long-term biopsychosocial management of multimorbidity.58 Based on the preliminary results of the Aging Film Series, creative and innovative attempts to confront these challenges show excellent potential for bolstering resident and staff morale, and establishing a therapeutic, rehabilitative culture. Future research on film use should more rigorously measure resident outcomes, perhaps utilizing short surveys to assess attendee reaction after each movie. Screenings might be followed by formally structured group discussions, during which residents collectively reflect on and process the films’ impact. The program described here was cost-effective and required limited time commitments. It can serve as a prototype for other facilities and can be modified in accordance with implementation strategies most appropriate for a particular setting and patient population.

References

1. Ouslander JG. Medical care in the nursing home. JAMA. 1989;262(18):2582-2590.

2. Besdine RW, Rubenstein LZ, Cassel C. Nursing home residents need physicians’ services. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(7):616-618. https://annals.org/article.aspx?articleid=707284. Accessed July 24, 2015.

3. Gawande A. Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books; 2014.

4. Morley JE, Flaherty JH. Putting the “home” back in nursing home. J of Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(7):M419-M421. https://biomedgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/content/57/7/M419.full. Accessed July 21, 2015.

5. Tolson D, Morley JE, Rolland Y, Vellas B. Improving nursing home practice: an international concern. Nurs Older People. 2011;23(9):20-21.

6. Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy Aging: Helping People to Live Long and Productive Lives and Enjoy a Good Quality of Life. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/6114/. Accessed July 2, 2013.

7. Bachmann S, Finger C, Huss A, Egger M, Stuck AE, Clough-Gorr KM. Inpatient rehabilitation specifically designed for geriatric patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c1718.

8. Castle NG, Engberg J. Staff turnover and quality of care in nursing homes. Med Care. 2005;43(6):616-626.

9. Bowers BJ, Esmond S, Jacobson N. The relationship between staffing and quality in long-term care facilities: exploring the views of nurse aides. J Nurs Care Qual. 2000;14(4):55-64.

10. Jones CS. Person-centered care. The heart of culture change. J Gerontol Nurs. 2011;37(6):18-23.

11. Van Malderen L, Mets T, Gorus E. Interventions to enhance the Quality of Life of older people in residential long-term care: A systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(1):141-150.

12. Kane RA. Long-term care and a good quality of life: bringing them closer together. Gerontologist. 2001;41(3):293-304.

13. Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Tappen R, et al. Interventions to reduce hospitalizations from nursing homes: evaluation of the INTERACT II collaborative quality improvement project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):745-753.

14. Tyler DA, Parker VA. Nursing home culture, teamwork, and culture change. J Res Nurs. 2011;16(1):37-49. Published online ahead of print April 26, 2010.

15. Koren MJ. Person-centered care for nursing home residents: the culture-change movement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(2):312-317.

16. Bower P, Kennedy A, Reeves D, et al. A cluster randomised controlled trial of the clinical and cost-effectiveness of a ‘whole systems’ model of self-management support for the management of long- term conditions in primary care: trial protocol. Implement Sci. 2012;7(7):1-13.

17. Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1985.

18. Bandura A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman & Company; 1997.

19. Resnick B. Efficacy beliefs in geriatric rehabilitation. J Gerontol Nurs. 1998;24(7):34-44.

20. Resnick B. Testing a model of exercise behavior in older adults. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(2):83-92.

21. Resnick B. Functional performance and exercise of older adults in long-term care settings. J Gerontol Nurs. 2000;26(3):7-16.

22. Resnick B, Gruber-Baldini AL, Zimmerman S, et al. Nursing home resident outcomes from the Res-Care intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(7):1156-1165.

23. Michael KM, Shaughnessy M, Resnick B. People Reducing Risk And Improving Strength through Exercise, Diet, and Drug adherence (PRAISEDD): a case report on long-term single site adoption. Translational Behav Med. 2012;2(2):236-240.

24. Sarkar U, Ali S, Whooley MA. Self-efficacy as a marker of cardiac function and predictor of heart failure hospitalization and mortality in patients with stable coronary heart disease: findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Health Psychol. 2009;28(2):166-173.

25. Sarkar U, Fisher L, Schillinger D. Is self-efficacy associated with diabetes self-management across race/ethnicity and health literacy? Diabetes Care. 2006;29(4):823-829.

26. King DK, Glasgow RE, Toobert DJ, et al. Self-efficacy, problem solving, and social-environmental support are associated with diabetes self-management behaviors. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(4):751-753.

27. Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2469-2475.

28. Holman H, Lorig K. Patient self-management: a key to effectiveness and efficiency in care of chronic disease. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(3):239-243. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1497631/. Accessed July 23, 2015.

29. Hoenig H, Nusbaum N, Brummel-Smith K. Geriatric rehabilitation: state of the art. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45(11):1371-1381.

30. Chen Q, Kane RL, Finch MD. The cost effectiveness of post-acute care for elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Inquiry. 2000-2001;37(4):359-375.

31. Brusco NK, Taylor NF, Watts JJ, Shields N. Economic evaluation of adult rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in a variety of settings. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(1):94-116. Published ahead of print April 3, 2013.

32. Pehrsson DE, McMillen PS. Bibliotherapy: A review of the research and applications. American Counseling Association Digest (Charter Series). Alexandra, VA: American Counseling Association; 2007.

33. Crothers SM. A Literary Clinic. Atlantic Monthly. 1916;118:291-301. www.unz.org/Pub/AtlanticMonthly-1916sep-00291. Accessed July 25, 2015.

34. Apodaca TR, Miller WR. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of bibliotherapy for alcohol problems. J of Clin Psychol. 2003;59(3):289-304.

35. Joling KJ, van Hout HP, van’t Veer-Tazelaar PJ, et al. How effective is bibliotherapy for very old adults with subthreshold depression? A randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(3):256-265.

36. Floyd M. Bibliotherapy as an adjunct to psychotherapy for depression in older adults. J Clin Psychol. 2003;59(2):187-195.

37. Gregory RJ, Schwer Canning S, Lee TW, Wise JC. Cognitive Bibliotherapy for Depression: A Meta-Analysis. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2004;35(3):275-280.

38. Scogin F, Jamison C, Gochneaur K. Comparative efficacy of cognitive and behavioral bibliotherapy for mildly and moderately depressed older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57(3):403-407.

39. Scogin F, Hamblin D, Beutler L. Bibliotherapy for depressed older adults: a self-help alternative. Gerontologist. 1987;27(3):383-387.

40. Moss K, Scogin F, Di Napoli E, Presnell A. A self-help behavioral activation treatment for geriatric depressive symptoms. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16(5):625-635.

41. Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(4):430-439.

42. Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37-43.

43. Friedman MJ. Acknowledging the psychiatric cost of war. New Engl J Med. 2004;

351(1):75-77. www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMe048129. Accessed July 23, 2015.

44. Sharma B. Elderly abuse: An emerging public health problem. Health Prospect. 2012;11:57-60. www.nepjol.info/index.php/HPROSPECT/article/download/7438/6033. Accessed July 23, 2015.

45. Bartels SJ, Naslund JA. The Underside of the Silver Tsunami—Older Adults and Mental Health Care. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):493-496. www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmp1211456. Accessed July 23, 2015.

46. Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Level CL, Freedland KE, Carney RM. A Multidisciplinary Intervention to Prevent the Readmission of Elderly Patients with Congestive Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1190-1195.

47. Dans PE, Kerr MR. Gerontology and Geriatrics in Medical Education. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:228-232.

48. Perissinotto CM, Stijacic Cenzer I, Covinsky KE. Loneliness in older persons: a predictor of functional decline and death. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1078-1083.

49. Moyle W, Skinner J, Rowe G, Gork C. Views of job satisfaction and dissatisfaction in Australian long-term care. J Clin Nurs 2003;12(2):168-176.

50. A Word From the President: MCAT 2015: An Open Letter to Pre-Med Students. Association of American Medical Colleges Website. www.aamc.org/newsroom/reporter/march2012/276772/word.html. Published March 2012; accessed July 24, 2015.

51. Peabody FW. The care of the patient. JAMA. 1927;88(12):877-882.

52. Parsons T. The Social System. Glencoe, IL: Free Press/Macmillan;1964.

53. Pennebaker JW. Opening up: The Healing Power of Confiding in Others. New York, NY: William Morrow & Co; 1990.

54. Rhodes R, Strain JJ. Trust and Transforming Medical Institutions. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2000;9(2):205-217.

55. Hall MA, Dugan E, Zheng B, Mishra AK. Trust in physicians and medical institutions: what is it, can it be measured, and does it matter? Milbank Q. 2001;79(4):613-639.

56. Street RL Jr, Makoul G, Arora NK, Epstein RM. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(3):295-301.

57. Long Term Care Institute Inc. Website. www.ltciorg.org/. Accessed July 24, 2015.

58. Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(4):430-439.