Surviving Post-COVID: Reducing Avoidable Emergency Department Visits and Hospital Admissions

Unnecessary emergency department (ED) use by older adults is of concern from both a clinical and financial perspective. For skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) to recover financially post-pandemic, they will need to keep their facilities full, which will in no small part be dependent on their ability to reduce avoidable ED/hospital use. This will not only improve financial outcomes but also, most importantly, clinical outcomes, for an increasingly frail SNF population. There are multiple areas of opportunity that providers/facilities can direct their energies to improve facility performance.

Avoidable ED utilization continues to be an issue for SNF providers. Despite a drop in SNF ED admissions due to COVID-19 concerns and overall decrease in SNF occupants, this remains an area of opportunity for greater efficiency and enhanced processes.

Unnecessary ED use by older adults is of concern from both a clinical and financial perspective. Clinically, there is increased risk for an iatrogenic event, such as a nosocomial infection or adverse drug reaction. Hospital-acquired infections typically occur in the form of urinary tract infections, nosocomial pneumonias, and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, which are most often preventable.1 Financially, SNF payment is increasingly being tied to how well a SNF performs in caring for its SNF residents, calculated by using ED use and hospitalizations as Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Quality Measures (QMs). Specifically, these QMs include the volume of long-stay residents with either ED visits or hospitalizations. This information is being utilized by hospitals in their decisions on whether or not to accept nursing homes (NHs) into their preferred networks, which is critical for securing a steady flow of patients into an SNF, ie, the financial health of an SNF.

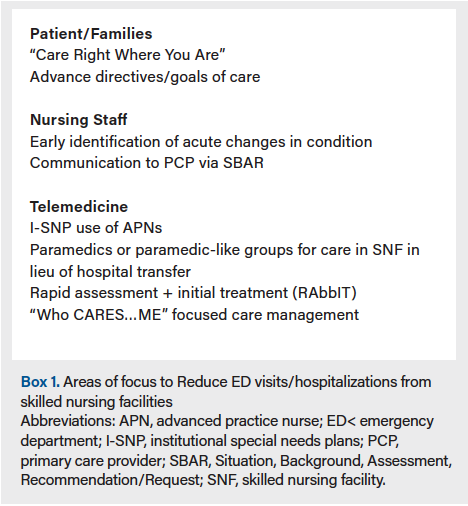

Thus, for clinical and financial reasons, reducing avoidable ED and hospital use remains a key focus for SNFs. There are multiple areas of focus (Box 1) that providers/facilities can direct their energies to improve facility performance in these measures. Strategies in these areas will involve several key SNF stakeholders and will require review of various SNF processes—from admission to discharge procedures—with downstream outcomes in mind.

Patient/Family Preparation

Reduction of avoidable ED use starts well ahead of the question being raised to send an SNF resident to the ED. The process begins at the time of admission to the SNF. Many proactive SNFs are starting to educate patients and their families of the benefits and scope of services available at the SNF during the initial admission process. This strategy has been formalized under the campaign called “Care Right Where You Are.”2 There is a double meaning within this phrase—“right” care refers to the correct care as well as care that is provided “right” where an SNF resident is at, ie, the facility, instead of being transferred elsewhere. For many patients and families, this is a novel concept, as most believe the safest environment for an older adult is the ED or hospital. Of course, for most, nothing could be further from the truth, as demonstrated by the high percentage of iatrogenic illness plaguing older adults

in the ED/hospital environment. This fact should be communicated to older adults and their families at time of admission.

Also at the time of admission, providers should have a discussion with each patient and family to gain an understanding of their goals of care. The federal requirement under the 1990 Patient Self Determination Act3 mandated that all health care facilities receiving federal aid, such as SNFs, inform their patients of their right to make decisions about their medical care, including the right to refuse treatment and right-to-die options. Unfortunately, in practice, this mandate has devolved to facilities simply asking patients if they have an advance directive and, if not, do they want information to complete one. Instead, providers should take this opportunity to have a robust discussion and to not only complete an advanced directive but also to document a clear understanding of each patient’s goals of care. This information is critical to ensure that patients wanting care provided in the SNF are not inappropriately transferred to the ED for care they neither want nor need.

Primary Care Provider Access

Goals-of-care discussions are the starting point for how SNFs will plan appropriate care for residents. Management of patients’ care goals relies heavily on the availability of primary care providers (PCPs). Increasing PCP access through telemedicine is one tool that can be utilized to assist in this endeavor. Telemedicine expansion was accelerated by COVID-19 but was been shown to be beneficial even prior.4,5 Specifically, one study in a 365-bed SNF in March 2015 examined the potential clinical and financial impact of an after-hours physician coverage service enabled by technology, TripleCare, to prevent avoidable hospitalizations.6 The study demonstrated that, of the 313 patients cared for by the telemedicine-enabled physicians during the year of service, 259 (83%) were treated on site (including 91 who avoided hospitalizations as verified by a third party), and 54 were transferred to the hospital. This reduction in ED use was estimated to save Medicare and other payers in excess of $1.55 million, approximately $500,000 of which went to a managed care Medicare payer in this single SNF. For an average 120-bed SNF, this would result in an annual savings of $500,000 to Medicare, or $4167 per bed. These data show how use of a dedicated virtual after-hours physician coverage service in an SNF can result in significant reduction in avoidable hospitalizations and cost savings.

Beyond the use of telemedicine PCP services, savings have been realized for some time by institutional special needs plans (I-SNP) that utilize dedicated advanced practice nurses (APNs) within an SNF. As an example, SNPs like UnitedHealth Group’s Optum program (previously Evercare) was shown to reduce ED/hospitalizations. In a study assessing this program, findings demonstrated that, in comparison with fee-for-service institutionalized Medicare beneficiaries, I-SNP members had 51% lower ED use, 38% fewer hospitalizations, and 45% fewer readmissions, whereas their subacute use was 112% higher.7

Increasing access to PCPs can also be achieved through alternative methods like the use of paramedics or paramedic-like mobile care organizations, such as DispatchHealth. DispatchHealth provides mobile APN and medical assistants who can go directly to patients’ homes upon patient requests, but they also directly contract with SNFs to decrease ED visits for patients with acute needs in facilities.8 DispatchHealth states that they are able to perform a number of procedures that would otherwise result in a trip to the ED. These same services can also be provided by paramedic groups, but all aim to treat individuals right where they are so as to avoid an ED visit.9

Of course, despite these advances, there are times that the scope of services needed for a comprehensive assessment and initiation of treatment are not readily available within an SNF or other partner organization. In these situations, a hospital admission can still be avoided through the application of a rapid assessment and initial treatment process (RAPT, also sometimes referred to as RAbbIT).10

RAbbIT can be utilized within an ED or an urgent care center to avoid an ED visit. In such situations, an SNF resident should be sent with the specific understanding by all that the purpose is for a rapid assessment of the issue and, when appropriate, initial treatment where the initial treatment can be provided with follow-up treatment provided in the SNF (eg, care for a deep venous thrombus or pneumonia).

In advance of the need for an acute PCP assessment, there are of course opportunities for the PCP to proactively focus on prevention. This can be accomplished by enhanced focus on the components described through the acronym “WHO CARES…ME”: Wellness (ie, vaccinations), Coordinated care, Acute care, Rx management, End of life, Social determinants of health, and MEntal health. Focusing on better care in these areas is essential for proactive prevention of unnecessary hospital/ED visits. Many of these elements, such as vaccination and coordination of care with a specialist, is often missed, resulting in progression of a chronic condition that requires acute care. In each of these areas, the importance of other members on the care team should be noted, such as consultant pharmacists who can assist in medication management, thus preventing the occurrence of an adverse event.

Nursing on the Frontline

Perhaps one of the most critical members of the care team are the nursing staff that stand firmly on the frontline. Nursing staff present 24/7 in the SNF are best positioned to identify concerns early. Such concerns need to be clearly articulated to available PCPs via the SBAR method, ie, Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation/Request.11 AMDA–The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care (PALTC) has developed several clinical practice guidelines that can assist in reducing ED/hospital use. One in particular, the Acute Change in Condition Clinical Practice Guideline, is focused on identifying acute change of conditions (ACOC) to enable nursing staff to evaluate and manage a patient within the SNF. To achieve this goal, the facility’s nursing staff are educated to recognize an ACOC, identifying its etiology, severity, and cause(s).12 The approach to recognition, assessment, treatment, and monitoring of ACOCs proposed in this guideline is aimed at improving management, thus reducing ED/hospital use.

The findings of an ACOC can be communicated by the SNF nursing lead to the PCP via SBAR or, in some cases, to the ED physician who can act as a guide for directing the care within the SNF, thus again avoiding a trip to the ED. This process is very much dependent on the skill of the nursing staff and their ability to communicate their findings to a PCP who then provides appropriate direction.

Improvement Is a Process

Implementing strategies to reduce unnecessary hospitalizations is not, of course, a one and done process but rather requires a consistent team effort. One tool to help in this way is INTERACT. INTERACT is “a publicly available quality improvement program that focuses on improving the identification, evaluation, and management of acute changes in condition of SNF residents.”13 Studies have demonstrated that effective implementation of INTERACT is associated with substantial reductions in hospitalization of SNF residents.13 In addition, INTERACT implementation can assist SNFs in meeting CMS Quality Assurance & Performance Improvement requirement.

SNFs should not only be focused on care within their four walls but also beyond into the community. Historically, like hospitals, care facilities have focused solely on the care in their buildings. This has shifted now to where hospitals are required to focus on successful transitions of care into the community to avoid readmissions. For SNFs to hold them accountable for successful transitions to the community, there are two CMS QMs that focus on how well a SNF does in transitioning its patients from a subacute stay back to the community (Box 2). These measures include the rate of potentially preventable hospital readmissions 30 days after discharge from an SNF and the percentage of short-stay residents who are rehospitalized after a NH admission. For SNFs to recover financially post-pandemic, they will need to keep their facilities full, which will in no small part be dependent on their ability to reduce avoidable ED/hospital use. This will not only improve financial outcomes but also, most importantly, clinical outcomes, for an increasingly frail SNF population.

References

1. Riedinger JL, Robbins LJ. Prevention of iatrogenic illness: adverse drug reactions and nosocomial infections in hospitalized older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 1998;14(4):681-698.

2. Manzi J, Saffel D. Care right where you are: treating in place to avoid an emergency department visit or hospitalization. Caring Ages. 2020;21(4):8. doi:10.1016/j.carage.2020.04.005

3. Patient Self Determination Act of 1990, HR 4449, 101st Cong (1989-1990). Accessed January 25, 2021. https://www.congress.gov/bill/101st-congress/house-bill/4449

4. Driessen J, Castle NG, Handler SM. Perceived benefits, barriers, and drivers of telemedicine from the perspective of skilled nursing facility administrative staff stakeholders. J Appl Gerontol. 2018;37(1):110-120. doi:10.1177/0733464816651884

5. Driessen J, Bonhomme A, Chang W, et al. Nursing home provider perceptions of telemedicine for reducing potentially avoidable hospitalizations. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(6):519-524. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2016.02.004

6. Chess D, Whitman JJ, Croll D, Stefanacci RG. Impact of after-hours telemedicine on hospitalizations in a skilled nursing facility. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(8):385-388.

7. McGarry BE, Grabowski DC. Managed care for long-stay nursing home residents: an evaluation of institutional special needs plans. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(9):438-443.

8. How it works. Dispatch Health. Accessed January 25, 2021. https://www.dispatchhealth.com/how-it-works/

9. DeCherrie L. Community paramedicine is at the forefront of homecare medicine. American Academy of Home Care Medicine. Accessed January 25, 2021. https://www.aahcm.org/page/cp#

10. Cronin JG, Wright J. Rapid assessment and initial patient treatment team--a way forward for emergency care. Accid Emerg Nurs. 2005;13(2):87-92. doi:10.1016/j.aaen.2004.12.002

11. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. SBAR tool: situation-background-assessment-recommendation. Accessed January 25, 2021. https://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/SBARToolkit.aspx

12. State of Michigan, Licensing and Regulatory Affairs. Clinical process guideline: acute change of condition (ACOC). Accessed January 25, 2021. https://www.michigan.gov/lara/0,4601,7-154-89334_63294_27655_31223_35790-108902--,00.html

13. Ouslander JG, Bonner A, Herndon L, Shutes J. The INTERACT quality improvement program: an overview for medical directors and primary care clinicians in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(3):162-170. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2013.12.005