Strategies for Managing Individuals With Behavioral Health Needs in Aging Services

ECRI Institute and Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging (ALTC) have joined in collaboration to bring ALTC readers periodic articles on topics in risk management, quality assurance and performance improvement (QAPI), and safety for persons served throughout the aging services continuum. ECRI Institute is an independent nonprofit that researches the best approaches to improving health care.

While the concept of “behavioral health” emerged over 40 years ago, the meaning of this phrase has evolved. Today, many people think of behavioral health as synonymous with mental health, but there is a subtle difference between the 2 terms.1 Mental health, as defined by the World Health Organization, is a “state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community” and can include disorders like bipolar disorder, depression, and anxiety disorder.2 Behavioral health disorders, on the other hand, stem from “maladaptive behaviors that negatively impact” an individual’s physical or mental condition such as gambling, addition, and substance abuse.1

Past approaches to meeting individuals’ behavioral health care needs in aging services settings have focused on particular needs, specific settings, or some other single component of the issue. Those approaches are important and may be necessary at times. However, aging services leaders and champions for individuals with behavioral health needs should consider analyzing the big picture and developing an overarching vision and plan for meeting these particular health needs throughout the continuum of care. Such efforts can help set a course for the organization and inform the selection of more specific goals.

Gain Leadership Support and Form a Strategic Team

To be effective, an initiative to better meet individuals’ behavioral health needs requires the support of leaders and frontline staff, as well as any committees that need to approve or monitor the progress of the initiative. Framing the initiative in a strategic, mission-focused manner may help earn leadership support. Formal or informal discussions or surveys can help establish the initial landscape of attitudes, concerns, and ideas about how to improve.

Even with leadership support in place, improving the care of individuals with behavioral health needs is often approached with “tunnel vision,” focusing on one particular issue in one particular setting. Again, such focus may be helpful and necessary at times, but, given the frequency with which persons served in aging services have behavioral health needs and given their transitions from care setting to care setting, leadership should consider examining the issue from a broader perspective.

To that end, forming a strategic team with leader support may be helpful in evaluating current strengths and gaps in meeting behavioral health needs and in developing a vision and goals for the future. The strategic team should include both organizational leaders and direct care staff. To better identify gaps in processes and service, the organization should also consider involving a resident and family member. Departments and disciplines that should be represented may include the following:

- Administrative and clinical leaders

- Resident safety, quality improvement, and risk management

- Behavioral health and social services

- Specific care units

- Security

Once the strategic team has been formed and has identified goals and projects, the team may want to complete the work itself or assign it to other groups or individuals, depending on the resources and structure of the organization and the attendant work. Some projects may be largely focused within one department; others may cross multiple disciplines. Depending on the project, individuals or departments that may carry out the work include those that could serve on the strategic team, as well as any of the following that are applicable:

- Legal affairs, the ethics committee, and accreditation

- Finance and billing, insurance, utilization management, and public relations

- Health information management, information privacy and security officers, and informatics

- Human resources, medical staff coordinator, occupational health, staff education, and teaching programs

- Diagnostic imaging and phlebotomy

- Pharmacy

- Facilities and building management

Evaluate Strengths and Gaps

To evaluate strengths and gaps, the strategic team may need to collect and analyze data, review current policies and other documents, identify existing resources and tools, and talk with stakeholders. Much of the information collected at baseline may form the basis for monitoring of continued improvement efforts as the initiative progresses.

A variety of means may be used to collect information. Community health needs assessments should specifically consider needs and existing resources related to behavioral health. Other potential sources include analysis of departmental logs or reports (eg, incident reports, administrative data, risk management data), manual or electronic chart review, observation, and surveys of providers or patients. Some events may call for more in-depth review instead of or in addition to quantitative tracking. Periodic group discussions, walkarounds, and informal discussions with stakeholders, including residents and families, may provide qualitative information that would not otherwise be captured.

Results of proactive or reactive analyses may provide valuable insights. One method, failure mode and effects analysis, is a proactive, systematic method of identifying and addressing ways in which processes can go wrong.3 Lean Six Sigma methodologies may also facilitate a proactive approach.4 Reactive analyses, which are performed after an event, may yield important insights into opportunities for improvement. For example, root-cause analyses may be conducted for adverse events related to behavioral health issues. The Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety model can be used both proactively and reactively. The model includes the work system, processes, and outcomes. It conceptualizes the work system as encompassing the person (eg, provider, patient, nonclinical staff member), the physical environment, organizational conditions, tasks, and technology and tools—all of which interact with one another.5

When evaluating strengths and gaps, the team may seek quantitative and qualitative information in several domains. In assessing quality of care for this population, the team may consider aspects such as how timely and effectively individuals’ behavioral health symptoms are managed and what impact the care encounter has on the individual after discharge or transfer to another care level. The National Quality Forum has endorsed many measures related to behavioral health.6 To assess safety, the team may examine self-harm, medication-related issues (eg, medication interactions, unintended discontinuation of psychiatric medications), restraint usage, elopement, and common medical safety events.

Measures of participation in or resistance to care and involvement of family members (if the resident desires) may be other areas for investigation, along with resident satisfaction and complaints. Staff-related measures may address issues such as workplace violence (including verbally aggressive behaviors and near misses), injuries and workers’ compensation claims, recruiting and retention, attitudes and stigma, and employee satisfaction. The team should also consider how the care of residents with behavioral health needs affects other individuals who do not have such needs; for instance, other residents may wait longer for medical care because of problems with throughput. Risk management, security, and legal concerns may include lawsuits, informed consent and health care decision making, health information privacy, interactions with law enforcement, frequency and types of security response, and presence or use of prohibited materials (eg, alcohol or other substances, weapons) on campus.

These are only examples. The strategic team should identify metrics important to the facility’s specific resident population and to the organization. Finally, a comprehensive examination of the business case may consider how this issue affects costs and revenue.

Formulate a Vision

Informed by the analysis of strengths and gaps, the strategic team should formulate a vision for meeting individuals’ behavioral health needs. This vision can, in turn, support the development of other strategic statements, such as specific goals.

For many organizations, a major hurdle is the dearth of behavioral health providers in their region. However, organizations can embed behavioral health resources into care settings, and they can collaborate with other health care providers, government agencies, payers, advocacy groups, and other stakeholders to improve access to behavioral health resources in their region. The process of formulating a vision may inform both actions that can be taken within the organization as well as opportunities to collaborate with other stakeholders.

Support is growing for the integration of behavioral health and medical care. Although the movement for behavioral health integration often focuses on integration of behavioral health into primary care, aging services organizations should consider whether such integration is in line with their broader mission, vision, and goals.

Developing an overarching plan can help turn the vision and other strategic statements into reality. Organizational leaders will need to maintain a behavioral health plan based on identified needs and resources. Because community needs and resources change, the organization should periodically reevaluate strengths and gaps and update the plan as needed.

Article continues below figure.

Advocate for Broader Change

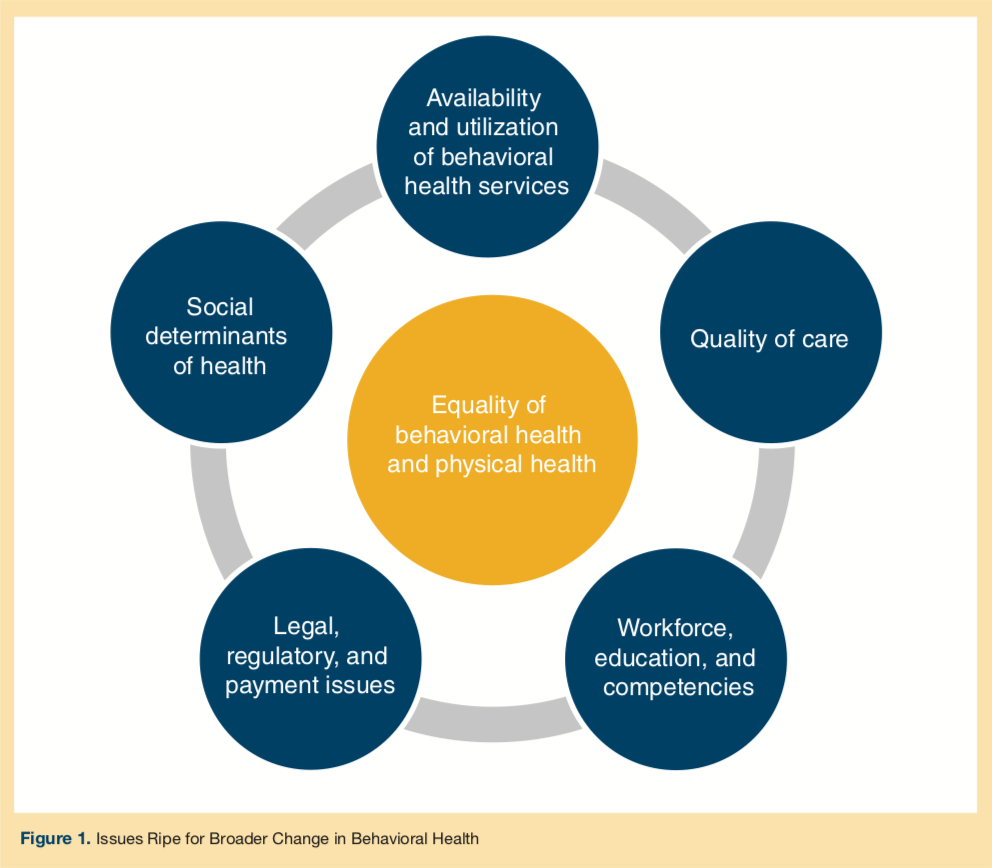

Many of the challenges that organizations face in meeting individuals’ behavioral health needs have roots in the ways society views and provides treatment for behavioral health. Along with their parent organizations and partners, leadership or health care professionals working in aging services settings may advocate for change at the regional, state, or federal level. See Figure 1 for domains in which health systems and their partners may engage. Below are examples of potential focus areas under each domain:

Equality of behavioral health and medical health. As discussed in the section “Formulate a Vision,” health systems may consider integrating medical and behavioral health. Organizations may help spread positive messages about behavioral health and seek to reduce stigma. Parity in insurance coverage is still sometimes an issue, as not all health plans are subject to parity laws.

Availability and utilization of behavioral health services. A community is likely to need access to a range of behavioral health services and supports beyond outpatient counseling and inpatient beds. Organizations may wish to identify mismatches between availability—in terms of services, capacity, and hours of availability—and need. Analysis of utilization patterns may help identify other barriers to appropriate utilization. Such efforts can help communities identify strategies.

Quality of care. Gaps in the quality and timeliness of behavioral health interventions can affect individuals with and without behavioral health needs. In addition to measuring quality within their own settings, aging services organizations may seek evidence-based guidelines on specific topics and help identify gaps in the evidence.

Workforce, education, and competencies. Aging services organizations may, for example, help spur interest in behavioral health professions by collaborating with media outlets, K-12 schools, community colleges, and 4-year institutions. They may also work with health professions schools to identify behavioral health competencies for both medical and behavioral health care workers. Loan repayment programs may help attract providers.

Legal, regulatory, and payment issues. Organizations may consider lobbying for changes to laws and regulations or working with payers to address concerns. Topics may include reimbursement levels and restrictions, insurance authorization, licensing and credentialing, emergency psychiatric holds and involuntary commitments, and telehealth requirements. Leadership may also consider developing collaborative relationships and protocols with law enforcement, emergency medical services (EMS), and other first responders.

Social determinants of health. Health literacy and access to health care, particularly primary care, are among the social determinants of health.7 Other determinants include housing, public safety, social context (eg, discrimination, incarceration), healthy foods, education, literacy and language, culture, employment, transportation, and even recreational activities.

Along with their parent health systems and behavioral health partners, leadership may consider engaging or partnering with groups such as the following:

- People with behavioral health needs, their families, and advocacy groups

- Government agencies, legislators, and payers

- Law enforcement and the justice system

- Behavioral health, public health, and social services

- Organizations that address social determinants of health (eg, housing, transportation, employment)

- Other providers across the care continuum (eg, acute care, primary care, EMS)

- Health care and policy researchers

- Health professions schools and professional societies

- K-12 schools, community colleges, and 4-year institutions

- Media outlets

Conclusion

Aging services providers encounter individuals with behavioral health needs in all of their care settings. Residents may be admitted with these needs or may develop them over time; as providers take on short-stay patients and others with higher acuity, they may be even more likely to encounter behavioral health needs. By developing a comprehensive strategy with leadership support, they can be prepared to promote the best possible outcomes.

A free download of the Executive Brief and more information about the full report, ECRI Institute PSO Deep Dive™: Meeting Patients’ Behavioral Health Needs in Acute Care, is available at https://www.ecri.org/behavioralhealth.

References

1. API Alvarado Parkway Institute Behavioral Health System (APIBHS). The difference between mental and behavioral health [blog]. apibhs.com website. https://www.apibhs.com/blog/2018/5/17/the-difference-between-mental-and-behavioral-health. Published May 10, 2018. Accessed November 15, 2018.

2. World Health Organization (WHO). Mental health: a state of well-being. who.int website. https://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/. Updated August 2014. Accessed November 15, 2018.

3. Failure mode and effects analysis. A hands-on guide for healthcare facilities. Health Devices. 2004;33(7):233-243.

4. American Society for Quality (ASQ). Lean Six Sigma in healthcare. asq.org website. https://asq.org/healthcaresixsigma/lean-six-sigma.html. Accessed November 15, 2018.

5. Carayon P, Schoofs Hundt A, Karsh BT, et al. Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(suppl 1):i50-i58.

6. National Quality Forum. Behavioral health measures. qualityforum.org website. https://www.qualityforum.org/Behavioral_Health_Endorsement_Maintenance.aspx. Accessed November 15, 2018.

7 US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Social determinants of health. healthypeople.gov website. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Accessed November 15, 2018.