Standardization of Standing Orders in Long-Term Care

Standing orders (SOs) are widely used in long-term care facilities (LTCFs) to improve efficiency. SO content varies across facilities and frequently lacks an evidence base, raising concerns from a quality and safety perspective. The aim of this project was to create a consensus-based SO set grounded in high-quality evidence, clinical practice guidelines (CPGs), and expert opinion for approval and use by multiple practices/providers across multiple facilities. A purposive sample of SOs from 13 diverse Minnesota NHs was compiled into one SO document. Revisions were based on a coalition of geriatric experts’ opinions and achieved content validity when they were satisfied with the contents.

Key words: standing orders, clinical protocols, long-term care, nursing home, culture change, organizational innovation

Wide individual variation of clinical care is a contributor to poor-quality patient care and is driven by provider reliance on individual clinical autonomy. This is especially true in the field of geriatrics, where care is often consensus-driven due to lack of representation of older adult patients in high-quality clinical research. Lack of standardization in care provided is often cited as one of the reasons health care performances are far below acceptable levels of quality.1 Continued efforts to adopt standardized practice approaches, using existing high-quality evidence and literature, are crucial to informing practice.

According to Martin,2 standing orders (SOs) are based on a state’s practice acts for physicians and nurses, allowing physicians to “delegate certain duties, tasks and responsibilities to licensed individuals whose license, training, education or experience qualifies them to perform the duties. The delegated acts or functions thus are technically deemed to fall within the scope of the physician’s professional practice.” She further defines SOs as “written instructions or procedures prepared by a physician and designed for a patient population with specific diseases, disorders, health problems or symptoms. Such instructions delineate under what conditions and circumstances action or treatment should be instituted.” Because SOs represent a delegated medical function, a physician or the medical director of a facility must approve the use of these orders, and nurses using these orders should verify that the orders fall within their state’s Board of Nursing scope of practice.2

SOs are widely used in long-term care facilities (LTCFs) to improve the efficiency of nursing care. SOs are written in the form of a non-resident specific protocol that is approved and signed by an authorized provider. These orders allow nurses and other qualified staff to carry out medical orders per a practice-approved protocol without the authorized clinician’s examination or requirement for individual approval.3 Nursing home (NH) staff rely heavily on SOs to treat their patients, and, despite broad use in LTC settings, SO content varies across NH venues and frequently lacks an evidence-based approach, often reflecting the individual medical director’s experience and desires. It is common for clinicians working in LTC to practice in many different facilities. Variations in individual facility SOs are left to the interpretation of the clinician, who can be at a disadvantage in determining how that variation may impact their approach to patient care in a given facility. This inconsistency creates issues regarding cost containment, time management, a lack of data-driven decision-making, limited or no reimbursement for some services, and unnecessary notification of providers regarding certain orders that could be implemented based on a SO (In a conversation with A Romstad, DNP, APRN, C-GNP, March 21, 2014). A standardized approach to SOs in LTC represents an initiative to foster best practices and a signal to geriatric clinicians to move away from unwanted variations in practice.

The focus of this quality improvement (QI) project was to create a standardized SO protocol, based on high-quality evidence, clinical practice guidelines (CPGs), and expert opinions, which can be utilized across multiple LTCFs in Minnesota and endorsed by multiple provider groups working in those settings. A Minnesota-state based interdisciplinary group of geriatric primary care providers, who serve LTC residents, transitional care, assisted-living, and other senior living communities, identified the need for this QI project and served as the expert coalition. The main focus of this coalition group was to develop consensus on best clinical practice for patient care in geriatric care settings. The goal was to decrease unwarranted practice variation whenever possible and, by doing so, decrease the burden, inefficiencies, and risk of multiple different requirements and approaches to care by the various clinical practices.

The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that planned activities for this QI project did not meet the regulatory definition of research with human subjects, was not a systematic investigation, and was not designed to contribute to generalizable knowledge. Therefore, this project did not need IRB approval and was monitored by the faculty advisor associated with this QI project. All participants selected to participate in this QI project were given full verbal or written consent though all QI activities involved no risk to participants beyond that associated with their baseline normal working conditions.

Methods

Coalition Members

The coalition is composed of a consortium of Minnesota health care professionals including geriatric physician leaders, practice managers, nurse practitioners, and academics. The physician leaders have a long history of working in nursing facilities and some have also served as NH medical directors with American Medical Directors Association (AMDA) certification. All physician leaders within the coalition belong to large integrated medical systems or are employed by stand-alone organizations providing care exclusively to patients in LTC settings; they collectively represent 12 major health care organizations and approximately 345 geriatric providers. The coalition also includes participation from the regional Medicare Quality Improvement Organization (QIO), Stratis Health, as well as participation from Care Choice, a large cooperative of non-profit LTC organizations.

Since its inception, the coalition has focused on the development of best practice standards and consensus approaches to geriatric care including standardized protocols for anticoagulation monitoring, Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatments (POLST), as well as antibiotic and antipsychotic stewardship. In 2013, the coalition was able to successfully pool and redesign competing organizational SOs and transitional care SOs into one standardized and universally applicable SO protocol for transitional care facilities across Minnesota. This evidence-based protocol has now been implemented statewide. Coalition members and nursing staff noted after implementing those standardized transitional care unit (TCU) SOs that providers were no longer unnecessarily informed regarding issues that were now incorporated in the new standardized document. In addition, nurses were making full use of their clinical skills. It was after TCU SO standardization that the variation in NH facility SO documents became even more apparent to the coalition. Coalition members discussed and identified the need for a standardized approach to SOs in NHs and the enhanced potential for optimization and prioritization of nursing care delivery (In a conversation with A Romstad, DNP, APRN, C-GNP, March 21, 2014). They felt that creating a similar standardized, practice-approved, and evidence-based approach to commonly used protocols in NHs had the potential to improve the overall quality of care.

Needs Assessment

A needs assessment, employing structured telephone surveys and face-to-face interviews with the coalition members, helped capture the experiences of directors of nursing (DONs), nurse practitioners (NPs), and organizational leadership regarding SO use in the LTC setting. Questions posed to the coalition respondents are detailed in Figure 1.

Clinician Time Analysis

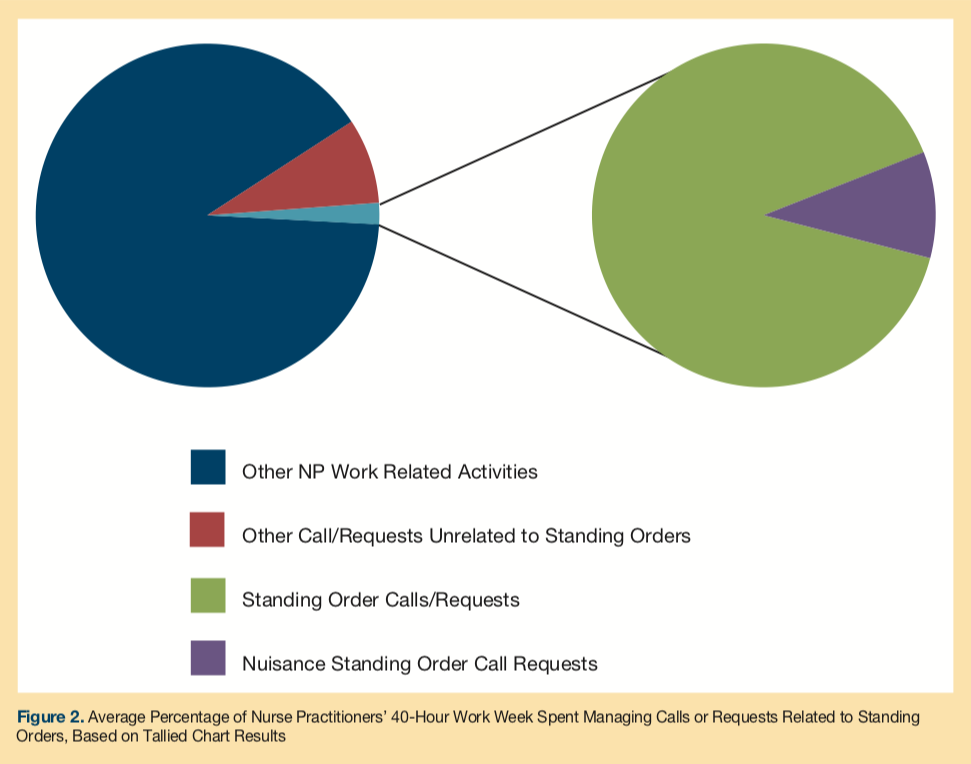

To determine the cost of the existing SO system in terms of provider time prior to standardization, a tally chart was distributed to a convenience sample of 9 willing coalition-affiliated authorizing providers that work in LTC to quantitatively evaluate and understand the time and effort undertaken to ensure appropriate delivery of current NH SO protocols over a five-day period. Providers were asked to report the average amount of time spent on calls or requests related to SOs, indicating whether or not the call was perceived as a nuisance. This tally chart allowed for a baseline quantitative evaluation of the frequency and amount of time spent on calls or requests related to SOs.

Development of the SO Document

Organizational learning theory was deemed the most appropriate framework applicable to the translation of knowledge into clinical practice. The integration of knowledge from high-quality evidence, care guidelines, organizational contextual factors, and relevant clinical experience was expected to enhance the dissemination and implementation of the standardized SO protocol in practice, making it more likely to positively impact the quality of resident care.4

To assess the current status of SOs, a purposive sampling technique was used to obtain a representative sample of 20 SOs from a variety of NHs. NHs were sampled based on Minnesota region, licensure, ownership, and size. Expert opinion was sought by an LTC expert from the Minnesota Department of Health to assist the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) student in identifying the most representative sample of NHs possible. The goal was to obtain a range of 12-20 different SO documents in order to better identify commonalities and outliers within the SOs. From the initial list of 20 NHs, the DNP student contacted the DON or individual responsible for ensuring that a SO document was in place in that facility. They were invited to participate in this QI project and, if in agreement, shared the facility’s SO document with the DNP student.

The facilities that were selected excluded SOs from transitional care or long-term acute care, rehabilitation units, assisted living, and psychiatric units. A total of 13 SOs were obtained from coalition-affiliated NHs for comparison. The final NH sample from which SOs were obtained was 62% urban and 38% rural, with a mean number of beds of 97.2 (median: 98; minimum: 40; maximum: 179). In terms of ownership, 62% were non-profit corporations owned by or affiliated with a religious organization, 15% were considered a proprietary “S” corporation (a private company that does not pay federal income tax and income and losses are divided between shareholders), 15% were considered a proprietary publicly held corporation (a private company with publicly traded stock), and 1% were considered a proprietary, closely held corporation (a private company owned by shareholders with no publicly traded stock).

In order to fully evaluate any variations in care, the diverse sample of SOs was compared and pooled into one homogeneous document. An integral part of the intervention phase of the project was a thorough literature search; this was completed in order to identify relevant evidence on geriatric preventive care and chronic disease management for the SO protocol. A substantial amount of literature was reviewed through a specific search of electronic databases for CPGs and English language studies. A guideline search was conducted using the National Guideline Clearinghouse, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and ClinicalKey. Additional search engines used included OVID Medline, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Google Scholar when relevant guidelines or systematic reviews were unavailable or more studies were needed for reference. Additional information from the Dynamed database, clinical textbooks, drug index systems, manufacturer recommendations, and national government websites were also referenced when appropriate. A total of 70 articles were included in the literature review that was used to guide rationale for the standardized SO document. Editorials and articles greater than ten years old were excluded from use, with most relevant citations found to be less than five years old. Exceptions were made when selected studies or guidelines were found that were essential to the topic under review.

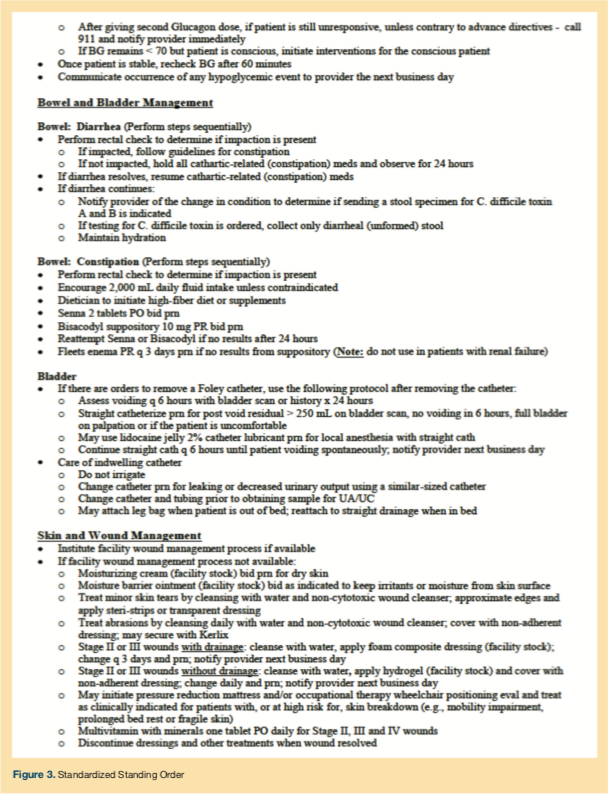

Draft revision of the standardized SO protocol took place at coalition quarterly meetings where all coalition members were encouraged to provide suggestions for modification to the first draft of the redesigned SO document. Any additional revisions were based on the coalition’s expert opinion and consensus among the providers of the coalition. This type of roundtable discussion provided an excellent venue for vetting the proposed SOs and engaging in in-depth discussions regarding SO content. After revising the document based on initial coalition feedback, the standardized protocol was distributed to the willing NH DONs. DON feedback allowed for revisions to the standardized protocol based on NH contextual factors. The second draft, inclusive of the DONs’ suggestions for revision, was presented to the coalition again in December 2014, where a similarly flexible and participative roundtable discussion took place. The new document achieved content validity by allowing the coalition to review and revise the document until they were satisfied with the contents. With coalition revisions and consensus on the document, coalition members were then charged with engaging NH facilities to adopt the standardized SO document. Refer to the final draft of the standardized LTC SO protocol in Figure 2.

In addition to the development of a standardized SO protocol, a separate rationale document was provided to the coalition with an evaluation of the standards, care practices, and CPGs used to govern each individual order. It is not within the scope of this article to speak to the individual evidence that guided the SOs. While the literature search was relatively comprehensive, it was not intended to be a systematic review and some relevant studies may have been missed.

Continued on next page

Results

Needs Assessment

The general consensus was that, while widespread and long-term adoption of a statewide SO protocol would be challenging in LTCFs, the development of an evidence-based, standardized, and practice-approved SO protocol would be an effective way to improve preventive care and chronic disease management in LTCFs. Results of the needs assessment suggested that, in order to enhance the likelihood of adoption, implementation, dissemination, and sustainability of the standardized protocol, care should be taken to integrate the relevant clinical care experiences of involved stakeholders with high-quality evidence. In addition, allowing opportunities for all parties to familiarize themselves with the protocol and its rationale would enhance the impact and uptake of the standardized SO protocol.

Clinician Time Analysis

Results of tally charts indicated that a seemingly insignificant amount of time in a full-time provider’s workweek was spent dealing with calls or requests regarding SOs. However, when this time was extrapolated into dollars, it was apparent that developing SOs provided an opportunity to improve provider productivity and contain costs. On average, among 8 full-time authorizing providers, roughly 1% of a full-time (40-hour) workweek is spent dealing with calls or requests regarding SOs, and 0.13% of that time is considered to be a nuisance (Figure 2). When extrapolating this time into dollars, based on a NP hourly wage of $46.12,5 $1,032.90 is spent per year per NP on calls or requests related to SOs. Of this amount, $120.10 is spent per year per NP on nuisance calls or requests related to SOs.

This dollar amount becomes quite substantial in terms of provider productivity when considering that organizations may employ hundreds of providers in LTCFs. The coalition represents 345 geriatric providers; over 200 are advanced practice providers (eg, NP, physician’s assistant). For example, when interpreting this data and accounting for only advanced practice nurses represented by the coalition, over $206,400 in time-dollars is spent per year on calls or requests related to SOs. Of this amount, $24,020 is spent per year on nuisance calls or requests related to SOs. In addition, the dollar amount may become more sizeable when considered for a physician or physician’s assistant salary, which was not evaluated in the needs assessment. Since this data was used to evaluate the current use of SO protocols prior to standardization, this data was not linked to any outcome data, but rather reinforced the need for this QI project.

Standing Order Document

The final SO document is depicted in Figure 3. A number of areas were determined to be of importance by the coalition members, including admission orders, immunizations, dietary guidelines, and disease/symptom management. The coalition expects that there will be additional revision to the orders once implementation in facilities takes place. However, the new SOs are more comprehensive than the multiple versions of the original SOs and are based on evidence grade, CPGs, consensus from medical directors in the coalition, as well as the practice managers (most of whom are NPs) representing their individual systems or practices. The accompanying guideline also allows for an improved revision process, as the original rationale is contained in that document.

Continued on next page

Discussion

Internationally, the literature on the efficacy and sustainability of preventive service and chronic disease-specific SOs unrelated to immunization services was found to be poorly reported.3 Existing literature on SOs based on practice guideline recommendations showed that SOs promote patient satisfaction, are cost-effective, and are a safe way to increase patient access to medical treatment through the optimal use of primary-care-based nursing skills.3, 6, 7 As we reviewed the literature, we did not find any robust analysis or evaluation of NH SOs, despite the fact that they are so commonplace throughout facilities in our community and the country. The authors were aware that there are vendors that have proprietary content regarding NH SOs and procedural protocols. However, since that content is not freely available, we felt that having community expert opinion and consensus based on community standards was a valid approach to this problem. Therefore, we feel the creation of common orders built on expert opinion and wide consensus is an important contribution to both literature and practice.

Evidence-based protocol formats are endorsed by numerous professional organizations including the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS),8 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),9 the Institute of Medicine,10 and AMDA.11 Unfortunately, the uptake and impact of care standards and guidelines into clinical practice is slow, particularly in LTC.12 Despite broad use of policies and protocols in daily NH practice, their basis in high-quality evidence is uncommon.13-14 The complex interactions between contextual, social, environmental, and organizational factors in LTC can contribute to stagnant care practices and resistance to practice innovations in this setting.13

Medicare or Medicaid imposing a regulatory emphasis on performance often drives practice change initiatives in LTC. Any outside QI initiatives can disrupt the internal organizational structure of an NH and threaten performance failure and termination of government funding.14-15 The majority of LTCFs do not engage in QI initiatives.16 Facilities that do engage in QI initiatives are often supported with funding outside of their government reimbursement income, are larger, chain-owned, for-profit or government-operated, in an urban location, and have the internal staffing capabilities and an autocratic leadership structure to buffer practice disturbances. 17-18

The integration of care standards and CPGs with knowledge about organizational contextual factors in LTC is critical to organizational success and quality patient outcomes and represent a solution to inconsistencies and variations in care.17-18 By integrating relevant clinical care knowledge in LTC, the ability to successfully disseminate, adopt, implement, and sustain any practice change is enhanced.12, 14

Our project contributes to national efforts to standardize care through the development and practice approval of a standardized, relevant, and evidence-based SO protocol for LTCFs. The project demonstrated that a broad coalition of providers from competing health care organizations, in conjunction with willing LTC administrators and medical directors, were able to work collaboratively to develop a mutually acceptable document that is expected to enhance the delivery of care in NHs by translating high-quality evidence into clinical practice. This project provides a template that can be implemented in other facilities, therefore enhancing the scarce literature regarding SO protocols.3

The most notable strength of this QI project was the actual development and approval of a relevant evidence-based standardized SO document that received endorsement from a Minnesota-based interdisciplinary coalition of geriatric primary care providers and a willing group of LTCFs. Prior to the development of these standardized SOs, there were no opportunities for continuity across NH venues in terms of chronic care and preventive disease management protocols. The development of standardized SOs was based on a needs assessment that included not only providers but end users of the product. Perceived wisdom used in the development of previous protocols was replaced by orders based on the best current evidence. The document with the supporting evidence is flexible enough to be revised as new evidence accrues. It is expected that the standardized SO protocol will play a vital role in assisting NH staff to improve patient safety, quality of care, clinical outcomes, and also contribute to national efforts to standardize care.

In addition to being consensus-driven and evidence-based, the SOs benefited from the direct involvement and expert opinion of relevant stakeholders in evaluating the usefulness of the protocol based on NH contextual factors and patient needs. The integration of NH management, practice managers, medical directors, and provider perspectives was also essential to the identification of barriers and facilitators to the successful implementation and dissemination of the standardized SO protocol. The meaningful participation of stakeholders helped to integrate the academic and clinical environments, which made the development and endorsement of a practical, patient-centered standardized SO protocol possible.

The results of this project support the contention derived from the organizational learning theory such that care guidelines, regulations, high-quality evidence, and relevant clinical knowledge and experiences of NH administrators and organizational leadership were translated into a relevant clinical protocol. These contextual factors are anticipated to enhance the dissemination and implementation of the standardized SO protocol in practice, making it more likely to positively impact the quality of resident care. Also consistent with organizational learning theory is that this standardized protocol will require ongoing review and updating as the protocol will continually be affected by complex and multidimensional interactions between the patient, environment, organization’s needs and experiences, and changes in evidence base.4 A conscious awareness of these interactions will contribute to the successful adoption and sustainability of the standardized protocol in practice.

In many ways, evidence-based care approaches and attempts to standardized care are strategies intended to improve care quality. Undeniably, the evidence-based methods employed in this QI project are a way to standardize, and not individualize, patient care in order to reduce clinical variances. Efforts were made to integrate individual clinician and patient experiences, situations, and preferences into the SO protocol where appropriate. The incorporation of relevant clinical knowledge with the high-quality data strengthens this protocol and can lessen some fears of clinical stereotyping.

The meaningful input, collaboration, participation, and enthusiasm of involved stakeholders from the 12 major health care organizations in the state of Minnesota and willing LTC administrators regarding the final content in the standardized SO protocol helped to account for real-world contextual NH factors and are likely to enhance the successful dissemination, adoption, implementation, and sustainability of this document in NHs. 3, 17 The collaboration and approval from involved stakeholders will help to minimize resistance to adoption of the SOs. Dissemination and implementation of this standardized SO protocol is intended to result in statewide and systematic execution across a large swath of LTCFs in Minnesota affiliated with the coalition.

Critics of this project may suggest that it dissuades patient-centered care and instead promotes a “cookbook” approach to care, rather than representing individual patient needs. The SO protocol is intended to be merged with relevant clinical knowledge and patient preferences in order to guide decision-making for authorizing providers and direct nursing staff. It is our opinion that, when properly applied to resident care, it will encourage more patient-centered care by clearly delineating appropriate treatment options from which the patient and provider may select. The final SO document is intended to allow for both provider discretion and patient preference to help drive assessments and interventions that bring about high-quality care. Critical review of the revised SO document may promote critique as to the wording of orders and what treatment options are considered acceptable. This is when the art of patient care should be employed, where treatment choices depend on patient preference as well as the best clinical evidence.

Several limitations arose throughout the course of the project that influenced project findings. The most significant study limitation was that the scope and timeframe of this project did not allow for addressing the implementation of the standardized SO protocol in individual NHs nor an evaluation of the influence and impact of standardized SOs on the quality of resident care. Additionally, the analysis of clinician time does not provide a compelling analysis of possible clinician errors or care mishaps that may occur as a result of poor execution of SOs or SOs that are poorly designed.

The process of streamlining and facilitating long-term adoption of the standardized SO document in LTC is predicted to be a great challenge that was not fully addressed in this QI project. Changes to any existing system can be difficult to execute and can be met with resistance. LTCFs may be asked to look at their care practices from a different perspective. The process of this change will create additional questions and concerns on the part of all providers and administrators, which will likely impede the process.

Agreement, alignment, adoption, and sustainability of the standardized protocol across NHs will be a difficult journey. Uptake of the standardized SO protocol will be impacted by limited NH resources (eg, financial, staffing), management and medical directors preferences, staff resistance, individual NH culture, and experience with culture and practice change. The relative ease of adherence and participation will not be equal across all NHs and the effort and enthusiasm of providers will not be sufficient to successfully implement this practice change in light of such barriers. Significant educational and structural efforts will be required in order to facilitate long-term adoption of the standardized SO document across LTCFs.

Once implemented, additional revision is likely to take place to improve clarity of the orders based on feedback from direct care nursing staff. After implementation, individual LTCFs may choose to use their own house nomenclature for certain orders on the standardized protocol and/or make addendums to the standardized document while still affording the coalition the exclusive rights to its use and distribution. However, changes would likely move away from the intent of standardization.

Conclusion

This project represents an opportunity to align recommendations from numerous professional societies and organizations such as CMS,8 the Institute of Medicine,10 and AMDA regarding the development and practical use of high-quality evidence in protocol formats with current practice. By decreasing unwarranted variability in care through the standardization of SOs across NHs, the quality, safety, consistency, and reliability of geriatric care may be improved through an evidence-based, coordinated, and collaborative approach to care. A more harmonized approach to preventive care and chronic disease management also has the potential to improve reimbursement, care coordination, and collaboration among interdisciplinary teams of health care. Through wide adoption of the standardized SO document, LTC practices can better meet the expected increased demand for high-quality, professional, and evidence-based geriatric care. This project is an attempt to standardize care given to LTC residents, so further evaluation and research is needed to determine whether standardizing orders helps improve patient, caregiver, and provider satisfaction, as well as patient outcomes. Future implications for research include disseminating and piloting the standardized protocol in selected LTCFs to better establish its efficacy. It is suggested that, prior to implementation, baseline data be collected and compared to post-implementation data in the select facilities where the SOs will be implemented. Alternatively, outcomes in facilities implementing the orders could be compared to outcomes in comparable facilities still operating under their current orders. Satisfaction of caregivers and patients could be evaluated in this manner as well. Finally, a business case for cost savings needs to be studied.

1. Reinertsen JL. Zen and the art of physician autonomy maintenance. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(12):992-995.

2. Martin RH. Standing orders: a much-utilized tool. Advance Healthcare Network Web site. Published June 11, 2001. Accessed February 1, 2016.

3. Nemeth LS, Orenstein SM, Jenkins RG, Wessell AM, Nietert, PJ. Implementing and evaluating electronic standing orders in primary care practice: a PPRNet Study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(5):594-604.

4. Argote L, Miron-Spektor E. Organizational learning: from experience to knowledge. Organ Sci. 2011;22(5):1123-1137.

5. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. 2011 AANP NP compensation survey: Recent graduate compensation. AANP Web site. http://www.aanp.org/education/student-resource-center/starting-your career/1059-2011-np-compensation-survey. Updated 2011. Accessed August 2014.

6. Mold JW, Aspy CA, Nagykaldi Z. Implementation of evidence-based preventive services delivery processes in primary care: an Oklahoma Physicians Resource/Research Network (OKPRN) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(4):334-344.

7. Scott-Jones J, Young F, Keir D, Lawrenson R. Standing orders extend rural nursing practice and patient access. Nurse N Z. 2009;15(3):14-15.

8. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Spotlight: Reform of hospital and critical access hospital conditions of participation: CMS-3244-F. CMS Web site. http://www.cms.gov. Updated January 1, 2015. Accessed June, 2014.

9. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Recommendations regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. Am J Prev Med. 2000; 18(supp 1):92-96.

10. Institute of Medicine. To Err is Human: Building a safer health system. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Web site. Updated November 29,1999. Accessed June 2014.

11. American Medical Directors Association. Health maintenance in the long term care setting. Columbia, MD: American Medical Directors Association; 2012.

12. Bostrom AM, Slaughter SE, Chojecki D, Estabrooks CA. What do we know about knowledge translation in the care of older adults? A scoping review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(3):210-219.

13. Colon-Emeric CS, Lekan D, Utley-Emith Q, et al. Barriers and facilitators of clinical practice guideline use in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(9):1404-1409.

14. Liu JY, Pang PC, Lo, SK. Development and implementation of an observational pain assessment protocol in a nursing home. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(11-12):1789-1793.

15. Banaszak-Holl J, Castle NG, Lin M, Spreitzer G. An assessment of cultural values and resident-centered culture change in U.S. nursing facilities. Health Care Manage Rev. 2013;38(4):295-305.

16. Zinn J, Mor V, Feng Z, Intrator O. Determinants of performance failure in the nursing home industry. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(5):933-940.

17. Berta W, Teare GF, Gilbart E, et al. Spanning the know-do gap: understanding knowledge application and capacity in long-term care homes. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(9):1326-1334.

18. Berta W, Ginsburg L, Gilbart E, Lemieux-Charles L, Davis D. What, why, and how care protocols are implemented in Ontario nursing homes. Can J Aging. 2013;32(1):73-85.