The Role of Directors of Nursing in Cultivating Nurse Empowerment

Affiliations: 1 Department of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania Health System, Philadelphia, PA 2 School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

Abstract: In nursing homes, directors of nursing (DONs) are responsible for cultivating nurse empowerment, yet they are often ill-equipped to do so. In this article, the authors explain the accountability–preparation gap, which affects the ability of DONs to create empowering work environments. The authors expand upon the results of a previous integrative literature review that elucidates how nurse empowerment is crucial to improving resident outcomes, particularly because empowerment can reduce staff turnover. The authors also identify three major barriers to empowerment: self-perception, lack of time, and lack of professional preparation. Practical implications of their review are discussed.

Key words: Quality of care, nurse leadership, nurse outcomes, resident outcomes, empowerment.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Many studies conducted within and outside of the nursing field have shown that positive practices by managers enhance employee empowerment.1-6 In nursing homes, directors of nursing (DONs) are the leaders responsible for such positive practices. A substantial body of the nursing literature suggests that when clinical nurses perceive themselves as empowered—able to take action, engage in decision-making, and take accountability for their practice1,7-10—both patient and staff outcomes are improved.8,11 In nursing homes, where issues of high staff turnover and poor quality of care continue to be pervasive, a clear need exists to empower nurses and improve outcomes for both staff and residents. Providing stable leadership aimed at cultivating clinical nurse empowerment is, therefore, an important aspect of the DON’s role.

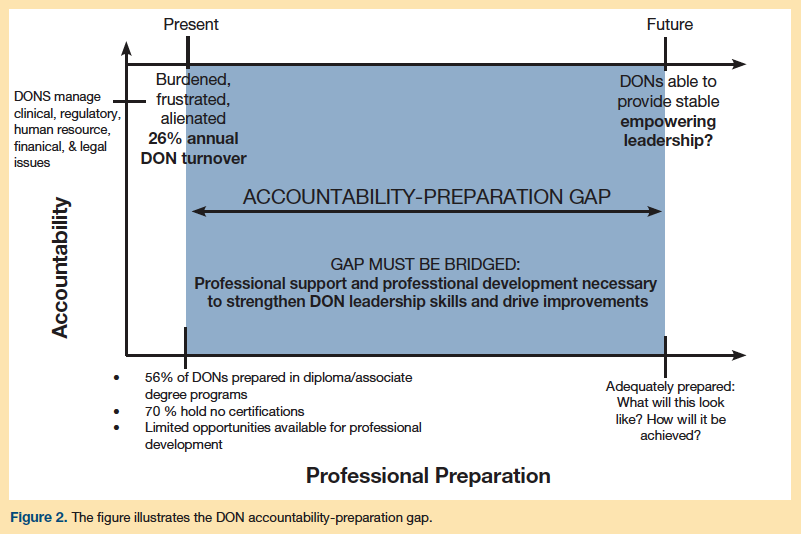

Yet, DONs are often ill-equipped to meet this need. In their roles, DONs are accountable for an overwhelming array of responsibilities they may not be prepared to assume. By virtue of the gap that exists between DONs’ high levels of accountability and low levels of professional preparation, both their own individual capacity for empowerment and their ability to cultivate healthy work environments in which clinical nurses feel empowered are diminished. This article briefly explains the concept of empowerment, followed by a review of the literature that describes the crucial role DONs should play in creating empowering work environments. It also elucidates the accountability-preparation gap that hampers their ability to do so. Empowering clinical nurses in nursing homes will likely benefit both nurses and residents, but without strengthening DON leadership effectiveness, these benefits are unlikely to be achieved.

This paper builds on a previous literature synthesis that broadly characterized the concept of empowerment through a search of multiple databases.7 A total of 44 publications were included in the study. In this paper, we explain the results of our search and offer several practical insights for long-term care providers.

Antecedents and Outcomes of Nurse Empowerment

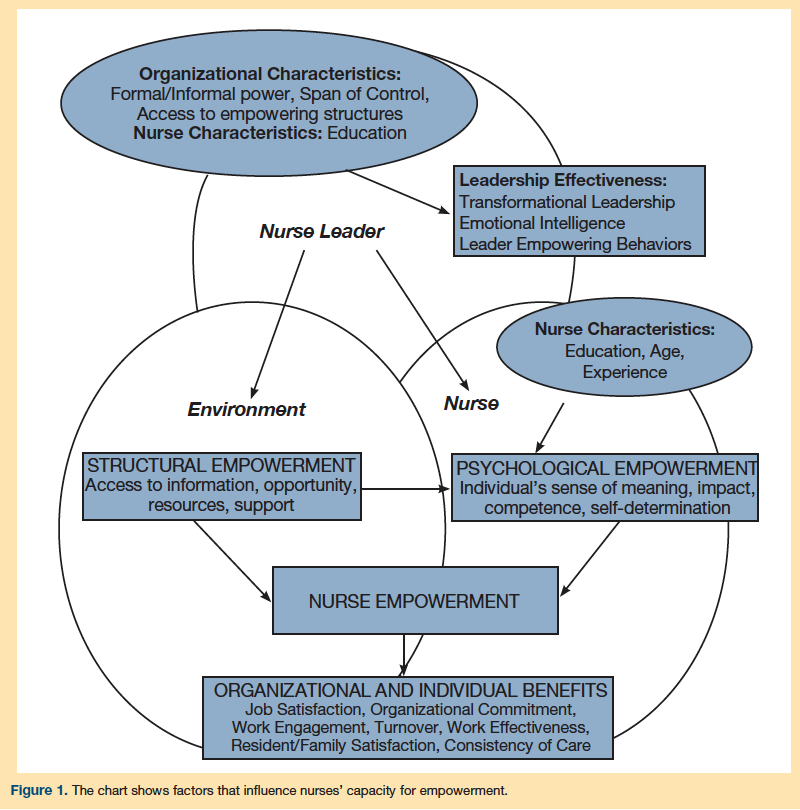

The literature characterizes nurse empowerment as a dynamic concept influenced by an interaction between organizational and individual-level factors.7,8,12,13 Organizational antecedents to nurse empowerment include the opportunities for mobility and growth and access to resources, support, and information provided within the nurse’s work environment.14,15 Concurrently, individual antecedents to empowerment include the nurse’s intrinsic motivation (ie, the nurse’s sense of meaning, competence, self-determination, impact16-18), educational preparation, and position within the organization (Figure 1).5,10,19

When empowered, nurses demonstrate increased participation in decision-making, increased autonomy over their practice,2 and a greater sense of organizational trust.20 Empowered nurses tend to be more satisfied with their jobs,15,21,22 and they experience an increased sense of organizational commitment,23 and quality of work life.2,6 They, in turn, experience less burnout and job stress and are less likely to leave their jobs or the profession all together.6,13 Further, when nursing turnover is decreased, empowerment is associated with improved care consistency and patient outcomes.22,24 In nursing homes, specifically, empowering practice environments—where nurses are meaningful partners in organizational decision-making, are supported by leadership and interprofessional colleagues, and have sufficient access to the resources needed to deliver care—are associated with reduced percentages of residents with pressure ulcers, fewer deficiency citations for noncompliance with regulations,25 and higher consumer satisfaction levels (Figure 1).19,21,22 Conversely, disempowering work environments—where nurses lack access to resources and leadership support and are not engaged in decision-making—contribute to adverse nurse outcomes, including burnout and turnover, the detrimental effects of which can contribute to the erosion of care standards.

The Role of Nurse Leaders

Nurse leaders cultivate empowerment through their leadership practices and influence in the work environment.2,5,6,26,27 Participative leadership practices employing shared decision-making strategies3,6,14 and transformational or emotionally intelligent leadership styles, in which leaders clearly articulate a vision for the organization and engage employees in achieving this vision by aligning their strengths with opportunities, giving them ownership of their work, and role modeling exemplary behaviors,2-5 are associated with increased nurse empowerment.2 Further, nurse leaders shape many of the organizational-level antecedents needed to cultivate nurse empowerment (Figure 1). They control access to opportunity and information and are responsible for allocating resources and providing support.5,26,28 To achieve the improved outcomes associated with nurse empowerment in nursing homes, DONs must provide leadership that engages clinical nurses as decision-making partners, coach and support them to grow professionally, and provide them with the resources and information they need to provide high-quality care.

The DON Accountability–Preparation Gap

Many of the studies investigating the antecedents and outcomes of nurse empowerment have been conducted in acute care settings focused on registered nurses (RNs). These studies demonstrate a clear association between empowerment and a number of positive outcomes. Acute care settings vary greatly from nursing homes, however, particularly with respect to the professional preparation of nursing staff members. Exploring these differences and the influence they have over the individual- and organization-level antecedents to empowerment suggests that cultivating empowerment in the nursing home setting presents unique challenges, which contribute to the gap (Figure 2). In the next sections, we will explore these challenges and offer several strategies to enhance the role of DONs and ultimately bridge this gap (Table).

DON Education and Issues of Self-Perception

Studies exploring the relationship between nurses’ levels of education and perceptions of empowerment demonstrate that nurses with bachelor’s degrees (BSNs) perceive themselves as more empowered than RNs with lower education levels,29 and nurses with master’s degrees or higher perceive themselves as more empowered than nurses with BSNs.19 The nursing home workforce is comprised primarily of licensed practical nurses, paraprofessionals, and RNs prepared in diploma or associate degree programs.22,30 As a result of these nurses’ relatively low levels of education, they have a reduced capacity for empowerment. They are, therefore, heavily reliant on DON leadership to create empowering work environments. Yet, DONs, too, have relatively low education levels. As such, their capacity for empowerment and ability to provide empowering leadership are diminished. Ultimately, DONs struggle to cultivate empowerment among nursing home nurses because they are overburdened with responsibility, underprepared, if not unprepared, to meet the demands associated with their roles, and disempowered themselves.

DON Responsibilities and Issues of Time

In their roles, DONs are accountable for both executive- and managerial-level responsibilities. Several professional organizations related specifically to long-term care and generally to nursing, have published largely congruent descriptions of DONs’ four core responsibilities and the knowledge and skills needed to fulfill them31:

1. DONs are responsible for overseeing the delivery of high-quality care for their residents. To do so, DONs must be able to apply geriatric and nursing knowledge to drive quality improvement initiatives and ensure that nursing practice in their facilities is evidence-based.

2. DONs have administrative responsibilities for designing systems that help their facilities and corporations meet established strategic goals. To provide this direction, DONs must be skilled critical thinkers, problem-solvers, and leaders able to implement quality assurance and improvement programs, coordinate efforts with other disciplines, maximize reimbursements while controlling costs, and ensure compliance with regulatory standards.31,32

3. DONs are responsible for human resource management, a responsibility that relates closely to their ability to create healthy work environments and empower staff. They must establish standards for conduct and hold their staff accountable to these standards, ensure their staff’s competency through oversight of professional development and education programs, provide support, manage conflict, and act as role models.

4. DONs are responsible for promoting a positive image of long-term care nursing by developing professional partnerships outside their corporations and reaching out to their communities.31

These high-level responsibilities elevate the role of the DON to a professional position beyond that which DONs often enact in practice. When surveyed about the activities in which they are most involved, DONs report that most of their time is spent on regulatory issues, staffing and scheduling, attending to conflicts, overseeing nursing care, and managing costs.32,33 One-third of their time is devoted to addressing resident and family concerns. Notably, they are least involved in high-level planning, staff development, community outreach, nursing research, and collaboration with nurse colleagues in other areas and organizations.32,33 Cultivating empowering work environments is only one of many key accountabilities assigned to DONs and, despite its importance, DONs have little time to devote to creating these structures.

DON Professional Preparation

The American Nurses Association recommended that nurses holding any administrative positions at the managerial level or above be minimally prepared with a master’s degree.34 This recommendation reflects the fact that prelicensure nursing curricula are focused mainly on clinical content, not leadership or management; to practice in an administrative role, nurses need to obtain adequate knowledge of management principles in an advanced-degree program.31 Yet, the 2004 National Nursing Home Survey reports that the majority (56%) of nursing home DONs were prepared in diploma or associate’s degree nursing programs.35 It also showed that 43% of DONs had some type of bachelor’s degree, but only 30% of DONs had bachelor’s degrees in nursing, and only 5% had master’s level preparation in nursing.31

These statistics suggest that DONs are formally educated at levels well below those needed to function most effectively in their leadership roles. Additionally troubling is the fact that DONs also have limited exposure to informal professional development opportunities, such as associations with professional organizations or achievement of specialty certifications, that would supplement their formal training.36,37 Involvement in such professional development activities connects nurses to external organizations, professionally significant information, and assistance that can enhance performance.36,37 Yet, only slightly more than 30% of DONs hold some form of professional certification, and only 12% of them are certified in nursing administration in long-term care.35 Further, less than 50% of these DONs belong to any of the professional organizations dedicated specifically to the professional development of nursing home DONs (eg, the American Association of Nurse Assessment Coordinators, the National Association Directors of Nursing Administration/Long Term Care, and the American Association for Long Term Care Nursing31). DONs’ limited professional preparation taken together with their high level of accountability creates the accountability–preparation gap (Figure 2). As a result of this gap, DONs have a low capacity for empowerment and are largely unable to address the various high-level accountabilities associated with their roles, including cultivating an empowering work environment.

DON Organizational Position

A DON’s position in the hierarchical corporate structure may further limit his or her capacity for empowerment at the individual level.38 DONs, particularly in for-profit organizations, report feeling disempowered with respect to autonomy,39 a finding echoed by frontline and middle managers in acute care settings who describe themselves as powerless and subordinate, believe they lack the resources necessary to achieve unit goals and support innovative programs, report limited decision-making power, and often feel forced to implement policies and programs they have not developed.40 Within individual nursing homes, DONs are geographically segregated from their DON peers and often operate alone as the nurse leader at the top of their facility’s management team. At the same time, they forfeit a great deal of autonomy because they are contained by the bureaucracy of the larger corporation. DONs are paradoxically positioned in a role with high accountability but low decision-making latitude.37,41-46 This constrained corporate position taken together with the burden DONs experience in their roles as a result of the accountability–preparation gap highlight the inherent difficulties DONs face in attempting to provide stable, empowering leadership to their clinical nurses.

Practical Implications and Solutions

There is clear consensus in the literature that nurse leaders are responsible for cultivating nurse empowerment and that nurse empowerment contributes to improved outcomes. The instability of a work environment with high turnover contributes to pervasive care quality issues: remaining staff members are burdened and overwhelmed; resident care consistency is jeopardized; and nurses and DONs are faced with a near constant uphill battle to deliver high quality care despite these everyday challenges.44 As a result, DONs struggle to create environments in which clinical nurses have access to opportunity, information, resources, and support. The Table summarizes several strategies to enhance the DON’s role.

Both the Advancing Excellence in America’s Nursing Homes campaign (www.nhqualitycampaign.org) and Medicare’s Quality Improvement Organization Program (https://bit.ly/CMS_QI) provide resources to address these complex challenges.47 These programs focus on improving care quality and strengthening the nursing home workforce. They create networks that support information exchange, provide tools to help leaders engage in quality improvement initiatives, and offer educational resources to build capacity among frontline staff and leaders. Many of these resources are freely available online. For example, a 200-page document titled Implementing Change in Long-Term Care: A Practical Guide to Transformation can be found on the Advancing Excellence campaign website.48 This document contains evidence-based information about leadership, teams, staff development, and change management along with organizational assessments that can be used to guide efforts, These resources have led to measurable improvements in nursing homes, and are therefore, valuable tools for DONs to explore.47 For DONs to be successful in applying these resources to their practice environments, however, they must have support from their colleagues, senior leaders, educators, and researchers.

Conclusion

The benefits of nurse empowerment and the role that DONs must play in cultivating empowerment are well defined in current literature; however, less attention has been devoted to uncovering barriers to DON leadership effectiveness. Before DONs can successfully empower their clinical nurses and drive much needed efforts to improve outcomes in nursing homes, the accountability–preparation gap must be bridged. Researchers must investigate how to strengthen DON leadership; industry leaders must invest resources in these vital leaders to strengthen their skills and provide the support needed to enhance their effectiveness; and educators must ensure that nurses early in their career are given the training needed to prepare them to function as leaders, not just in acute care settings, but in nursing homes, as well.

References

1. Seibert SE, Silver SR, Randolph WA. Taking empowerment to the next level: a multiple-level model of empowerment, performance, and satisfaction. Acad Manag J.

2004;47(3):332-349.

2. Lucas V, Laschinger HKS, Wong CA. The impact of emotional intelligent leadership on staff nurse empowerment: the moderating effect of span of control.

J Nurs Manag. 2008;16(8):964-973.

3. Laschinger HK, Wong C, McMahon L, Kaufmann C. Leader behavior impact on staff nurse empowerment, job tension, and work effectiveness. J Nurs Adm. 1999;29(5):28-39.

4. Doran D, McCutcheon A, Evans M, et al. Impact of the Manager’s Span of Control on Leadership and Performance. Toronto, ON: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; 2004:i–30.

5. Force MV. The relationship between effective nurse managers and nursing retention. J Nurs Adm. 2005;35(7-8):336-341.

6. Greco P, Laschinger HKS, Wong C. Leader empowering behaviours, staff nurse empowerment, and work engagement/burnout. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont). 2006;19(4):41-56.

7. Rao A. The contemporary construction of nurse empowerment. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2012;44(4):396-402.

8. Manojlovich M. Power and empowerment in nursing: looking backward to inform the future. Online J Issues Nurs. 2007;12(1):2.

9. Laschinger HKS, Wong CA, Greco P. The impact of staff nurse empowerment on person-job fit and work engagement/burnout. Nurs Adm Q. 2006;30(4):358-367.

10. Ellefsen B, Hamilton G. Empowered nurses? Nurses in Norway and the USA compared. Int Nurs Rev. 2000;47(2):106-120.

11. Anderson R, Issel LM, McDaniel Jr RR. Nursing homes as complex adaptive systems: relationship between management practice and resident outcomes. Nurs Res. 2003;52(1):12-21.

12. Laschinger HK, Finegan J, Shamian J, Wilk P. Impact of structural and psychological empowerment on job strain in nursing work settings: expanding Kanter’s model. J Nurs Adm. 2001;31(5):260-272.

13. Kluska KM, Laschinger HKS, Kerr MS. Staff nurse empowerment and effort-reward imbalance. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont). 2004;17(1):112-128.

14. Kanter RM. Men and Women of the Corporation. New York: Basic Books; 1977.

15. Ning S, Zhong H, Libo W, Qiujie L. The impact of nurse empowerment on job satisfaction. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(12):2642–2648.

16. Spreitzer GM. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad Manag J. 1995;38(5):1442-1465.

17. Thomas KW, Velthouse BA. Cognitive elements of empowerment: an “interpretive” model of intrinsic task motivation. Acad Manag Rev. 1990;15(4):666-681.

18. Spreitzer GM. A dimensional analysis of the relationship between psychological empowerment and effectiveness satisfaction, and strain. J Manage. 1997;23(5):679-704.

19. Donahue MO, Piazza IM, Griffin MQ, Dykes PC, Fitzpatrick JJ. The relationship between nurses’ perceptions of empowerment and patient satisfaction. Appl Nurs Res. 2008;21(1):2-7.

20. Laschinger HK, Finegan J, Shamian J, Casier S. Organizational trust and empowerment in restructured healthcare settings. Effects on staff nurse commitment.

J Nurs Adm. 2000;30(9):413-425.

21. Rondeau K V, Wagar TH. Nurse and resident satisfaction in magnet long-term care organizations: do high involvement approaches matter? J Nurs Manag. 2006;14(3):244-250.

22. Hostvedt KK. Nursing Homes as Organization: The Effect of Organizational System Characteristics on Resident and Nurse Outcomes [dissertation]. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania; 2008. https://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI3328579.

23. Kuokkanen L, Leino-Kilpi H, Katajisto J. Nurse empowerment, job-related satisfaction, and organizational commitment. J Nurs Care Qual. 2003;18(3):184-192.

24. Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET, Cheney T. Effects of hospital care environment on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2008;38(5):223-229.

25. Flynn L, Liang Y, Dickson GL, Aiken LH. Effects of nursing practice environments on quality outcomes in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(12):2401-2406.

26. Farrell D, Brady C, Frank B. Meeting the Leadership Challenge in Long-Term Care: What You Do Matters. Baltimore, MD: Health Professions Press; 2011.

27. Matthews S, Spence Laschinger HK, Johnstone L. Staff nurse empowerment in line and staff organizational structures for chief nurse executives. J Nurs Adm. 2006;36(11):526-533.

28. Bogue RJ, Joseph ML, Sieloff CL. Shared governance as vertical alignment of nursing group power and nurse practice council effectiveness. J Nurs Manag. 2009;17(1):4-14.

29. Morgan DG, Stewart NJ, D’Arcy C, Cammer AL. Creating and sustaining dementia special care units in rural nursing homes: the critical role of nursing leadership. Can J Nurs Leadersh. 2005;18:74-99.

30. DON certification exam. NADONA/LTC Online. www.nadona.org. Accessed February 20, 2015.

31. STTI. Sigma Theta Tau Leadership Institute. 2014. www.nursingsociety.org. Accessed February 20, 2015.

32. Suominen T, Savikko N, Kiviniemi K, Doran DI, Leino-Kilpi H. Work empowerment as experienced by nurses in elderly care. J Prof Nurs. 2008;24(1):42-45.

33. Committee on Improving Quality in Long-Term Care, Institute of Medicine, Division of Health Care Services. Improving the Quality of Long-Term Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2000.

34. Siegel EO, Mueller C, Anderson KL, Dellefield ME. The pivotal role of the director of nursing in nursing homes. Nurs Adm Q. 2010;34(2):110-121.

35. Aroian JF, Patsdaughter CA, Wyszynski ME. DONs in long-term care facilities: contemporary roles, current credentials, and educational needs. Nurs Econ. 2000;18(3):149-156.

36. Mueller CH. LTC directors of nursing define educational needs: long-term-care DONs want specialized education for their varied roles. Nurs Manage. 1998;29(11):39-43.

37. American Nurses Association. Nursing Administration: Scope and Standards of Practice. Silver Spring, MD: Nursesbooks.org; 2009.

38. Jones AL, Dwyer LL, Bercovitz AR, Strahan GW. The National Nursing Home Survey: 2004 overview. Vital Health Stat 13. 2009;(167):1-155.

39. Castle NG, Fogel BS. Professional association membership by nursing facility administrators and quality of care. Health Care Manage Rev. 2002;27(2):7-17.

40. Corazzini KN, Anderson RA, Mueller C, Thorpe JM, McConnell ES. Jurisdiction over nursing care systems in nursing homes: latent class analysis. Nurs Res. 2012;61(1):28-38.

41. Han S-K. Structuring relations in on-the-job networks. Soc Networks. 1996;18(1):47-67.

42. Kash BA, Naufal GS, Dagher RK, Johnson CE. Individual factors associated with intentions to leave among directors of nursing in nursing homes. Health Care Manage Rev. 2010;35(3):246-255.

43. Goddard MB, Laschinger HK. Nurse managers’ perceptions of power and opportunity. Can J Nurs Adm. 1997;10(2):40–66.

44. Dellve L, Wikström EWA. Managing complex workplace stress in health care organizations: leaders’ perceived legitimacy conflicts. J Nurs Manag. 2009;17(8):931-941.

45. Pousette A. Feedback and Stress in Human Service Organizations [doctoral thesis]. Sweden: University of Gothenburg; 2001.

46. Skagert K, Dellve L, Eklöf M, Pousette A, Ahlborg Jr G. Leaders’ strategies for dealing with own and their subordinates’ stress in public human service organisations. Appl Ergon. 2008;39(6):803-811.

47. Shih A, Dewar DM, Hartman T. Medicare’s quality improvement organization program value in nursing homes. Health Care Financ Rev. 2007;28(3):109-116.

48. Bowers B, Nolet K, Roberts T, Esmond S. Implementing change in long-term care: a practical guide to transformation. Advancing Excellence website. www.nhqualitycampaign.org. Accessed March 19, 2015.

Disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Address correspondence to: Aditi R. Rao, PhD, RN, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, 3400 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104; aditi.rao@uphs.upenn.edu

Acknowledgments: This work was supported by funding from the John A. Hartford Foundation’s Building Academic Geriatric Nursing Capacity pre-doctoral scholarship.