Reducing International Normalized Ratio-Related After-Hours Calls for Warfarin Monitoring

Skilled nursing facility (SNF) staff make many after-hours calls regarding international normalized ratio (INR) measurements for monitoring patients on warfarin. The volume of these calls is disproportionately high at various times, which can congest phone lines, disrupt continuity of care, and reduce quality of care. In a quality improvement initiative with OptumCare in 60 SNFs with 30 nurse practitioners, we sought to reduce INR-related after-hours calls by asking NPs to: use an evidence-based warfarin dosing protocol for adjusting warfarin and ordering follow-up INRs; use the CHA2S2-VASc to determine appropriateness of warfarin therapy; and order routine INRs for set days early in the week, so that NPs can order follow-up INRs before the weekend if needed. There was a statistically significant reduction in INR calls 1-month postintervention (P = .00013) and 9 months postintervention (P = .04) as well as a statistically significant reduction in facilities that called with INR-related calls (P = .04). Results suggest that NPs can reduce after-hours INR call volume through implementation of evidence-based dosing protocols and time management measures, potentially improving care quality and continuity of care.

Key words: INR, after-hours, reduction, call, international normalized ratio, call reduction

Many skilled nursing facility (SNF) residents receive warfarin to reduce the risk of cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs) associated with atrial fibrillation, valvular heart disease, or other coagulopathies, including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or previous CVAs. Warfarin has a narrow therapeutic index, requiring routine international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring with a goal range of 2.0 to 3.0, except in the presence of a mechanical heart valve in the mitral position, when the goal range is 2.5 to 3.5.1

At 60 OptumCare SNFs in Washington State, primary care physicians perform visits to SNF residents per Medicare requirements, but the OptumCare nurse practitioners (NPs) independently provide the majority of primary care services, including warfarin management, to SNF residents in partial fulfillment of Medicare Advantage Plan benefits. OptumCare employs NPs separate from the primary physician; thus, NPs and physicians work as colleagues in this model rather than in a supervisory relationship. This model of care focuses on providing frequent primary care visits with the goal of preventing unnecessary hospitalizations and establishing resident-specific goals of care.

Each NP cares for approximately 80 long-term and post-acute residents, usually in multiple SNFs. During nonbusiness hours, however, one after-hours NP covers all 60 SNFs. Communication of INR results is often done via fax or telephone. After-hours health care providers receive many calls from SNF staff reporting INR results, which congests after-hours lines. Line congestion has the potential to lead to unnecessary delays in care or hospitalizations if nursing staff are unable to reach after-hours providers with urgent patient concerns. Additionally, after-hours warfarin management has the potential to reduce continuity of care by unnecessarily involving multiple providers who may have differing methods for managing warfarin.

The aim of this study was to improve warfarin management in Washington State OptumCare SNFs by first collecting and evaluating baseline data and then implementing practice changes based on this evaluation. The goal of this quality improvement project was to reduce the volume of after-hours, INR-related calls in order to reduce after-hours line congestion, diminish delays in care, improve continuity of care, and improve the quality of warfarin management for SNF residents to potentially avoid unnecessary hospitalizations.

Methods

Setting and Participants

The study included 60 SNFs and the 30 OptumCare NPs that work in these SNFs. Each NP cares for approximately 80 long-term and post-acute residents, usually in multiple SNFs. One after-hours NP covers all 60 SNFs each day during nonbusiness hours.

Practice Evaluation

All calls received by the after-hours NP for the OptumCare SNF system were logged in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet that was kept on a shared drive to which all Washington NPs have access. Call log data from the month of December 2014 was used to detect trends and potential areas to address during practice change implementation. This information was only collected once in December of 2014.

Calls were initially sorted by the calling SNF and the day of the week after-hours INR calls were received. Data were then analyzed to determine: (1) the total number of after-hours calls that came in; (2) the proportion of the total number of after-hours calls that were INR monitoring-related; and (3) trends in the number of INR monitoring calls that came in during each day of the week to compare weekdays with weekend days.

In December 2014, there were 378 after-hours calls, and 59 were INR related (15.34% of the call volume). A disproportionate number of INR calls came in on the weekend (30 on weekdays and 29 INR on weekends). This was due to the NPs ordering INRs for the weekends. We identified this issue as a modifiable practice to target for quality improvement.

Additionally, the team’s 30 NPs were consulted as to what type of INR monitoring each SNF used. There are two methods for monitoring INRs in LTC. The point-of-care (POC) method involves a finger stick and subsequent collection of a single drop of blood into a test strip that is then read by a handheld meter in the facility. This provides rapid results for the nurse to report to NPs, so that orders can be written in a timely manner. In contrast, the lab-based method involves a phlebotomist coming into the LTCF, drawing blood, and taking it back to a lab for analysis. This process takes hours and often results in after-hours calls.

There is evidence of more time spent at a therapeutic INR with the POC INR-monitoring method when used with a standard dosing protocol.1-4 Additionally, lab monitoring may cause lag time between blood draws and reporting INR results.

The team’s NPs reported that, of the 60 SNFs, 56% were using lab-based monitoring, 36% used the POC method, and 8% used both methods. For the SNFs using POC testing, we identified the possibility of NPs asking nursing staff to check and communicate INRs earlier, so that providers can address results before the end of the business day, as a practice for quality improvement. However, there is little ability to control how long labs take to return INR results, so this factor is less modifiable. Facilities were not asked to change their method of monitoring as that had financial implications for the building. Instead, we asked the NPs to order POC INRs for day shift where available to reduce the number of calls from those buildings.

Practice Change Implementation

In February 2015, NPs received training on warfarin management improvement at the clinical staff meeting. NPs were asked to use an evidence-based dosing protocol (Figure 1) for ordering warfarin doses and follow-up INRs.5 The rationale was that an evidence-based protocol would improve INR stability, thus allowing longer INR-monitoring intervals and reducing the total number of INRs ordered.NPs were also asked to install applications on their company-provided smart phones that include guidelines for warfarin dosing and the CHA2DS2-VASc to determine patients who were appropriate candidates for warfarin therapy.6,7 The reasoning behind the mobile-phone applications was that all participating NPs were mobile, ie, providing care in multiple SNFs; thus, these applications were an easy way for them to access evidence-based guidelines and implement them without the need to carry paper-based protocols to each facility. The goal was to improve compliance through ease of accessibility and portability. Use of this protocol was not tracked or enforced, but management encouraged its use periodically throughout the intervention phase.

To address the issue of NPs ordering INRs for the weekends, we implemented an INR ordering schedule. NPs were asked to order routine INRs early on a set “INR day” (Tuesday or Wednesday), avoiding holidays and scheduled days off. We hypothesized that establishing an INR day early in the week would give NPs the ability to follow-up later in the work week as needed, thus avoiding scheduling follow-up INRs on weekends. The set INR day was also intended to establish a routine for nurses to follow up with NPs regarding INR results.

For the SNFs using POC testing, we identified the possibility of NPs asking nursing staff to check and communicate INRs earlier as a practice for quality improvement. NPs were asked to encourage nurses to obtain INRs and new orders on the INR day and early in the NP’s shift, so that the NP assigned to the SNF could have the opportunity to address results during business hours, rather than having them reported to after-hours providers. NPs were also asked to call their facilities at the end of the day to ensure that available INRs had been addressed. The goal of this practice change was to eliminate most after-hours INR calls on the weekdays.

In emails every 2 weeks through the month of March, NPs received refreshers and reminders on the content. NPs received refreshers on proposed practice changes including preferred set INR days (Tuesday and Wednesday), follow-up on out of range INRs by Friday, use of standard dosing protocols, use of the CHADS2-VASC tool to ensure appropriateness of anticoagulation, and ordering INRs to be done early in the day for buildings using the POC method.

Data Collection and Analysis

To evaluate the impact of the practice change on the volume of after-hours INR-related calls, we again evaluated data from the electronic call logs at two additional time points after the practice change was implemented: March 2015 (1 month after practice change) and November 2015 (9 months after practice change).

In addition to evaluating the total number of after-hours calls that came in, the proportion of the total number of after-hours calls that were INR related, and trends in the number of INR calls that came in during each day of the week, we also determined the total number of SNFs from which calls were received and evaluated whether there were differences in the number of calls received from SNFs that used lab-based monitoring vs those that used POC monitoring.

Microsoft Excel data analysis tools were used to analyze data from the call logs, and t-tests were used to determine statistically significant differences for the comparisons between December 2014 and the other two time points.

Results

Comparing call logs from March 2015 and December 2014 showed a statistically significant reduction in the number and percentage of INR-related after-hours calls between the 2 months (P = .00013; Table 1). Whereas INR-related calls represented 15.34% of the overall call volume before the practice change, only 7.48% of the calls 1 month after the practice change were INR related. This represents a 51.24% reduction in the proportion of after-hours INR-related calls. In November 2015, the number and percentage of INR-related calls increased (Table 1). However, the percentage of INR-related calls still represented a statistically significant reduction vs December 2014 (P = .04).

In December 2014, 25 of the 60 SNFs (42%) called after-hours regarding INRs (Table 1). Of those 25 SNFs, 12 only called with one INR result for the month, meaning that the majority of calls came from just 13 SNFs. In comparison, in March 2015, only 16 of the 60 SNFs (27%) called with INR results. This represents a statistically significant reduction in the number of SNFs making after-hours INR-related calls (P = .001). This was not sustained in November 2015, however; the number of SNFs that made after-hours INR calls increased to 27 (45%). This call increase in November was partially due to the large number of calls that came in over Thanksgiving and Black Friday, which comprised 34% (22 of 65 calls) of the total INR-related after-hours calls for the month.

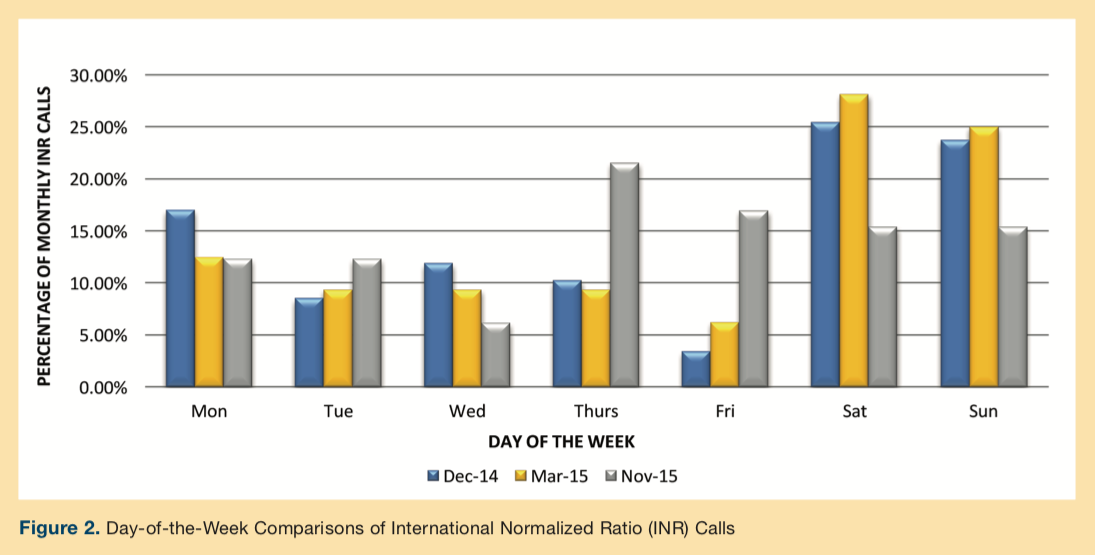

In December 2014 and in March 2015, a disproportionate number of INR calls came in on weekend days vs weekdays (Figure 2). In November 2015, the number of calls made on weekend days was similar to the number of calls made on weekdays; however, there was no statistically significant change in the number of INR-related calls on the weekends compared with those coming in on the weekdays across the three time points.

There was no statistically significant change in the number of calls coming in from SNFs using POC monitoring compared with those using lab-based monitoring. There was no statistically significant reduction in the number of INR calls received from buildings using the POC testing compared with those using lab-based testing in March 2015, P = .58, and in November 2015, P = .29.

Discussion

The congestion of after-hours phone lines due to excessive after-hours INR-related calls poses a potential problem, as it may prevent more urgent calls from being addressed quickly and efficiently. This study evaluated whether this problem can be lessened by implementing an evidence-based protocol for ordering warfarin doses and follow-up INR calls and establishing set days for routine INRs in order to reduce the number of INR-related calls made after hours.

Our findings suggested that our practice change was associated with an initial reduction in the volume of after-hours INR calls. There is still room for improvement, though, as weekends and holidays still received disproportionate amounts of INR-related after-hours calls. In regards to the increased percentage of INR-related calls in November (11.75%), which was partially due to the large number of calls that came in over Thanksgiving and Black Friday, this represents a need to reinforce the use of set days, such as Tuesday and Wednesday, as preferred days for routine INR testing.

The ordering of INR monitoring early on Tuesday or Wednesday, along with the standard dosing protocol, shows promise for reducing after-hours provider involvement in warfarin management. Reducing calls for routine INRs lessens line congestion, so providers can address urgent issues expediently, especially as the overall call volume continually increased throughout this study. Reducing line congestion may minimize delays in care and unnecessary hospitalizations. Indeed, unnecessary hospitalization were reduced during this project, but, as there were many initiatives aimed at this outcome simultaneously, it is impossible to know if this project had a direct impact. Future research, in a larger study, is needed to determine long-term patient outcomes to see if improvement is sustained and to see if there is any correlation with reduction in hospitalizations.

The use of an evidence-based dosing protocol likely helped to maintain continuity of care when INR calls came in, as both providers should be adjusting warfarin the same way. Future studies are needed to determine whether an evidence-based dosing protocol and greater continuity of care results in longer intervals between INRs.

Interestingly, several of the after-hours providers voiced improved job satisfaction as they felt that they were managing urgent concerns more effectively when they had fewer INR-related calls. This was not an outcome measured in this project; the effects of such initiatives on after-hours providers’ job satisfaction should be investigated in future studies.

Whether the reduction in INR-related calls was the result of the evidence-based protocol implementation, the INR-monitoring schedule, or both cannot be determined. Future studies should include measures to solidify the relationships between these practice changes and the number of INR calls coming in and to identify further areas for improvement.

Limitations of this study were that it did not directly address patient outcomes, and there was no control group. Additionally, as there is evidence of seasonal variation, future studies should include a longer baseline sampling to eliminate the effects of this variable on postintervention data. Also, NP compliance with requested practice changes was not specifically measured or enforced. Still, our results should have wide application due to the relatively large diverse sample of SNFs and NPs and due to the length of follow-up.

Conclusion

By implementing an evidence-based protocol for warfarin dosing and INR ordering, we were able to reduce both the number of INR calls and the number of facilities making a disproportionate number of INR-related calls, potentially improving continuity of care. Future projects should investigate ways to mitigate other sources of after-hours line congestion (eg, routine controlled-substance refills) to improve providers’ ability to attend to more urgent matters. These studies should include a larger baseline sample and a control group.

1. Rossiter J, Soor G, Telner D, Aliazadeh B, Lake J. A pharmacist-led point-of

care INR clinic: optimizing care in a family health team setting. Int J Fam Med. 2013;2013:691454.

2. Franke CA, Dickerson LM, Carek PJ. Improving anticoagulation therapy using point-of-care testing and a standardized protocol. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(supp 1):S28-S32.

3. Bluestein D, Brantley C, Barnes-Eley M, Gravenstein S, Basta S. Measuring international normalized ratios in long-term care: a comparison of commercial laboratory and point-of-care device results. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8(6):404-408.

4. Health Quality Ontario. Point-of-care international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring devices for patients on long-term oral anticoagulation therapy: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2009;9(12):1-114.

5. Ebell MH. A systematic approach to managing warfarin doses. Fam Pract Manag. 2015;12(5):77-80, 83.

6. Medical Services Commission. Warfarin therapy management. National Guidelines Clearinghouse website. Accessed April 16, 2015.

7. de Jong J. CHA2DS2-VASc/HAS-BLED/EHRA atrial fibrillation risk score calculator. chadsvasc.org website. http://www.chadsvasc.org/. Accessed April 16, 2015.