Reducing Antipsychotic Use Through Culture Change: An Interdisciplinary Effort

Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) represent the most common off-label use for antipsychotic medications. We implemented a quality improvement program using principles of culture change transformation for the staff and residents of a nursing home dementia unit with a goal of transitioning to a person-centered model and reducing the proportion of residents receiving antipsychotic medications with off-label indications. Staff members’ perceptions regarding the effects of the interventions were assessed through surveys. Of 39 residents living on the unit during the intervention and evaluation period, 94% (n=37) were women, 54% white, and 46% black. The mean age was 85.6 years. All residents had a diagnosis of dementia with BPSD documented in 62% (n=24). The proportion of residents receiving antipsychotic medication use was reduced from 18% to 5% (P = .009) with a concomitant reduction in sedative and anxiolytic use in the 3 months following implementation. Staff perceived a significant improvement in residents’ sleep quality and level of interaction. Certified nurse assistants reported they had a more significant role in the care of the residents.

Key words: antipsychotics, culture change, dementia, person-centered care model, staff satisfaction

Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) remain the most common reasons for off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the nursing home.1 Despite a black box warning by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2005 and efforts by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to reduce off-label prescribing, the prevalence of antipsychotic medication use remains high.2 The likelihood of a resident receiving an antipsychotic medication is related to the regional culture of dementia care and facility-level antipsychotic prescribing rates.3

One aim of the CMS National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes is to promote nonpharmacologic, person-centered approaches to dementia care, which are often instituted as part of a “culture change transformation”.4 White-Chu and colleagues5 describe the culture change revolution in long-term care (LTC) facilities by comparing the Traditional Medical Model vs the Culture Change Model through the following juxtapositions: staff providing treatments to patients vs nurturing the human spirit; being driven by facility routine vs following residents’ routines; staff having “floating” assignments vs permanent staff assignments; staff deciding for patients vs resident self-determination or staff decisions based upon nonverbal cues from residents; structured activities vs spontaneous activities; and viewing residents as patients with diagnoses vs residents as people.5

In this report, we describe a quality improvement (QI) initiative in which we implemented a staffing model with evidence-based protocols informed by the culture change model to promote person-centered care and create a sustainable person-centered environment in a LTC dementia unit. Through this QI program, the team’s ultimate goal was to reduce antipsychotic medication use.

Intervention Site and Participants

We targeted the dementia care unit of a not-for-profit nursing home with 48 beds. Planning regarding the program started during the second week of January 2014.

All residents on the unit, (N = 43) were included. Four residents died over the 6 weeks of planning before implementation, and five new residents were admitted after implementation and thus were not included in the evaluation of outcomes, which were collected 3 months after the intervention. Therefore, the total sample size for analysis was 39 residents. The residents were primarily women (94%; n = 37), 54% white, and 46% black. The mean age was 85.6 years. All residents had a documented diagnosis of dementia, with 62% (n = 24) having an additional documented diagnosis of BPSD. The most common comorbid conditions were hypertension (77%; n = 30) and diabetes (20%; n = 8). With regard to functional status, the residents had a high degree of dependence with a mean activities of daily living (ADL) score of 10.3 (range, 1-16, with 16 being totally dependent in all ADLs). Residents on average had been in the unit for 34.5 (range, 1-115) months at the time of the intervention.

Staff participants were the certified nurse assistants (CNA; N = 18) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs; N = 10) directly involved in the residents’ care. Staff members who worked on the unit temporarily (floating) were not included. As a QI program, the project was exempt from institutional review board review.

Planning and Implementation

The project involved all disciplines related to the care of the residents. The administrative team included the facility administrator, medical director, director of nursing, human resources, clinical nurse educator, and the scheduler. The disciplines with direct patient interaction were five clinicians (three doctors, one nurse practitioner, and one hospice nurse practitioner), a unit nurse manager, an activity director with her two assistants, and LPNs and CNAs on the unit. The team used a five-step strategy in the planning and implementation of the changes.

Gaining Buy-in

With the highly regulated nursing home environment, negotiating with facility administration to change existing practices that comply with state and federal regulations was anticipated to be a challenge. We conducted informal discussions with the direct patient care staff, individually and in small groups, asking for their thoughts regarding the residents’ routines. For example: Why do the residents have to dress early in the morning? Why are the residents sleepy? What strategies have been used previously to reduce antipsychotic use? What were the barriers to those changes?

The weekly behavioral meeting was also attended regularly to learn what strategies staff were using and what made their work difficult. During this meeting, the physician champion (PC) shared an article demonstrating that the probability of a resident being prescribed an antipsychotic depended on the facility’s prescription pattern, with Georgia being one of the worst states.2 Additionally, the provider shared that another nursing home on the same campus had recently achieved zero off-label antipsychotic medication use through a simple strategy of education and gradual dose reduction of these medications. These statistics garnered the attention of the team, from administrative staff to CNAs. Subsequently, an in-service was organized for each group. The administrator and clinical nurse educator received literature in addition to a one-on-one talk. The LPNs, the wound care nurse, social worker, and CNAs received a didactic presentation tailored to their distinct roles in the residents’ care. Topics included: symptoms and progression of dementia; creating a person-centered environment for residents; improving sleep quality; effective communication; appropriate activities for residents with dementia; creating opportunities for residents to give back to their community through resident-led activities; harnessing spontaneity and creativity; and enhancing coping skills. The didactic presentations also provided an opportunity to present the impact of the proposed QI program, including staff changes and the anticipated impact on their work burden and work flow.

Chart Review

The PC reviewed both paper and electronic medical records of all the residents. Residents on antipsychotic medications were identified. The indications for their use, and appropriate monitoring were also noted. Resident behavioral patterns, medication administration pattern, and timing were also reviewed.

Identifying Key Partners

Building an effective implementation team is necessary for on the ground support, leadership support, and implementation sustainability. The administrator, activity director, and unit nurse manager were identified as key interdisciplinary partners.

Developing the Work Plan and Staffing Model

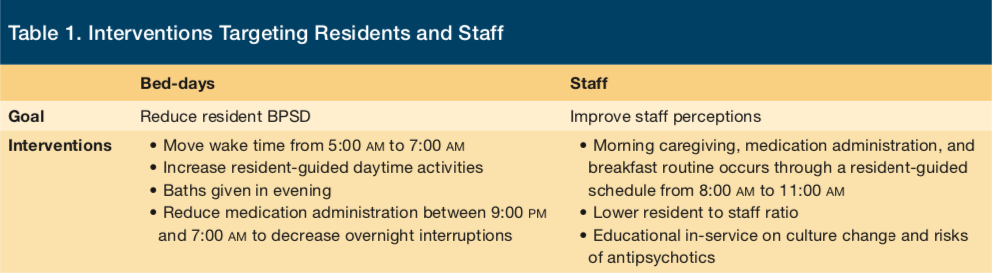

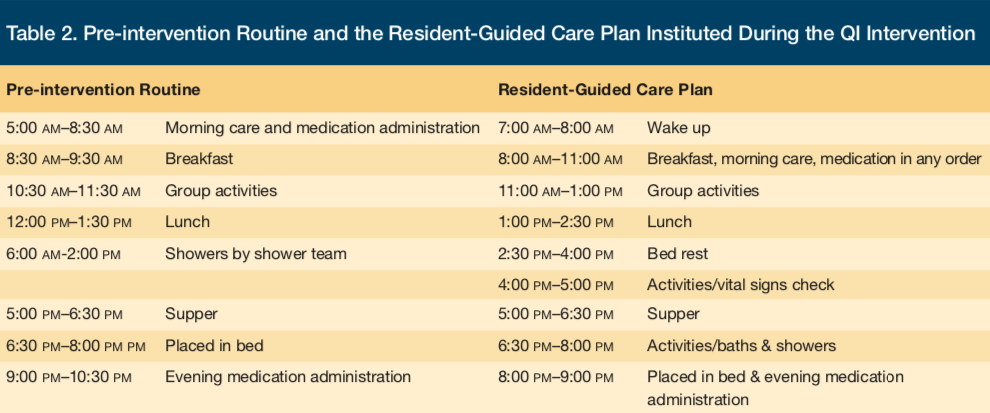

Six weeks prior to implementation, the PC worked with the implementation team, including the administrator, activity director, and unit nurse manager, to develop a set of interventions that would facilitate a resident-centered living experience and were feasible within current staffing models. See Table 1 for a summary of the aims and interventions of the QI project. We designed a guided daily routine with flexibility for the nursing staff (Table 2).

We assessed appropriate staffing ratios for the proposed changes and worked within the approved facility budget for staffing over a 24-hour period. Prior to implementation, there were two LPNs assigned for each 8-hour shift. We proposed moving one LPN from the night shift to the day shift in order to support the aims of the QI project. Prior to implementation, there were five CNA positions budgeted for the morning shift and two additional CNA positions assigned to assist with residents’ showers in the morning. The shower team had no Minimum Data Set (MDS) charting responsibility. We proposed adding these two CNAs to the morning staff and shifting one CNA from the night shift to provide a total of eight CNAs for the 7:00 AM–3:00 PM shift. We maintained the five CNAs for 3:00 PM–11:00 PM shift. The night team was reduced to three CNAs after moving one CNA to the morning team. Additionally, CNAs were given permanent resident assignments by dividing the residents according to their care burden. A resident assignment plan was created for a staffing model with eight CNAs and also for seven CNAs if a staff member was unable to report for work.

The first four steps occurred over a 6-week period. Before the changes were implemented, a new medication chart was obtained for the additional LPN for the morning shift and the scheduler was briefed on the new plan in order to provide the appropriate staffing needed per each shift. Prior to implementation, we conducted another in-service with all LPNs and CNAs to discuss the new work schedule on the dementia care unit.

Implementation

Implementation of the QI program occurred over a 2-week period. In the first week, we instituted the additional morning LPN with a new medication chart. The addition of one LPN to the morning team through a reduction in LPN staffing during the night shift led to the nurse-resident ratio from 1:24 to 1:16.

We removed the tasks that the direct patient care team had identified as not consistent with patient-centered LTC resident care such as frequent vital signs monitoring. Blood pressure monitoring was changed from 3 to 4 times per day to weekly for residents with hypertension and monthly for those without hypertension. Default parameters in the electronic medical record that required a resident’s blood pressure to be entered before medication administration were removed and only allowed for up to a week after the introduction of an antihypertensive drug. These changes created room for new tasks to be introduced without the team feeling overwhelmed.

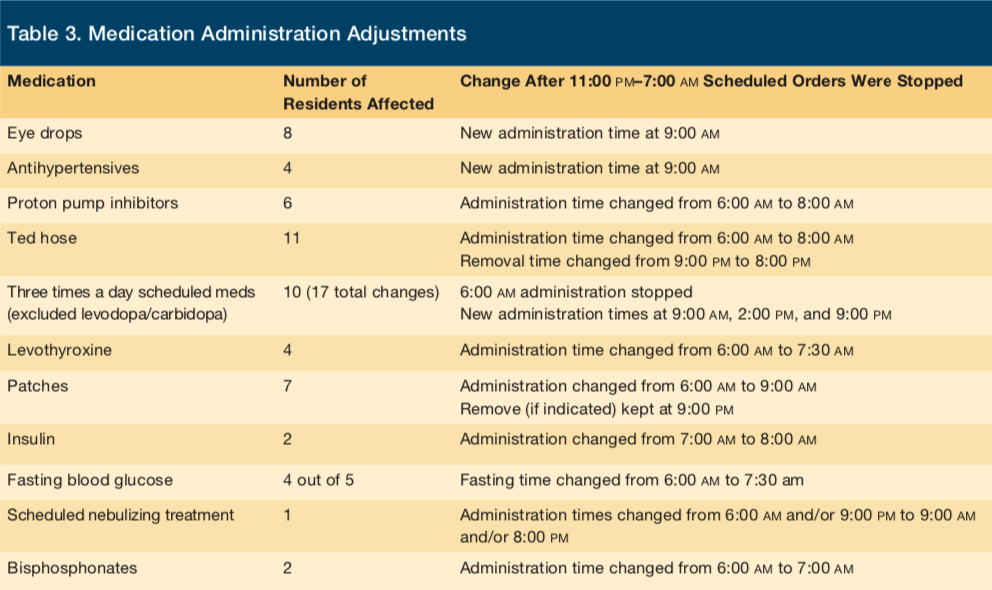

All scheduled medications times were changed to occur between 8:00 AM and 9:00 PM with the exception of a few medications that needed to be administered before breakfast such as proton pump inhibitors and bisphosphonates; in consultation with the facility pharmacy service, these medications were administered at 7:00 AM (Table 3). The implementation team provided support with frequent visits to identify any unanticipated challenges and create solutions in order to rectify them. The three LPNs were able to administer the morning medications beginning at 8:00 AM at a manageable pace.

No resident was awakened before 7:00 AM and once awake, residents were quietly taken care of without disturbing the rest of the unit. Previously, facility leadership and staff had believed that residents had to be dressed in day clothes before breakfast, in order to demonstrate respect for resident dignity. This practice led to residents awakening at 5:00 AM to take a bath and change into day clothes. In order to address leadership concerns that the facility could receive a citation related to the changes in resident apparel at mealtimes, the team thoroughly researched state guidelines. The team convinced facility leadership that residents could be awaken at 7:00 AM, dressed in a robe for breakfast, and delay a full shower or bath until later in the day.

Residents were more awake mid-morning to enjoy the activities, which now involved some of the CNAs assisting the Activity Team. Activities oriented toward women, such as manicures, hair styling, and dancing, were introduced as appropriate with the help of the Activity Team. CNAs were also able to integrate their own hobbies and interests into the daily activity program. Morning and afternoon activities lead by CNAs included cooking, crocheting, singing, exercising, and storytelling. Another activity period was introduced after supper in order to keep residents engaged until after evening medications were administered. Evening activities lead by nursing staff included puzzles, bible study, sing-alongs, and reminiscing in small groups. Some residents were offered baths during this evening time.

Residents were assigned to the same CNAs for their care, and the overall CNA-resident ratio during the day improved from 1:8 to 1:6. After staffing changes for CNAs were implemented, MDS charting, which occurred during the 7:00 AM to 3:00 PM shift, was reduced from 12 (four CNAs for 48 beds) to six (eight CNAs for 48 beds) per CNA. With the initiation of routine resident assignments, charting was less stressful, as staff members were more familiar with the residents and interacted with them more frequently during the day.

A work plan was created for the night staff. The only night LPN had no scheduled medications to administer and therefore had more time to attend to the needs of the residents and support other staff members. Thus, the LPN’s main function was to make frequent quiet rounds on the residents to make sure they were comfortable and provide additional support for CNAs working with residents in need or who had a tendency to wander at night. All staff were encouraged to work in a quiet environment so as not to wake the residents unnecessarily.

Lastly, after discussions with attending physicians and the resident’s psychiatrist, the clinician providers implemented gradual dose reduction for patients receiving off-label antipsychotic medications. These dose reductions were achieved over a 4-week period.

Challenges Encountered

In order to address any family concerns regarding changes proposed as part of the QI program, a family meeting was organized by the Activity Director and attended by the unit clinicians, including the facility medical director. The topic of the meeting was to discuss BPSD and the facility’s goal of using nonpharmacologic strategies for initial management. In the course of the interventions, only one family member declined a change in the timing of blood glucose monitoring and discontinuation of her family member’s off-label antipsychotic medication.

Previous research suggests the psychosocial networks (staff relationships and staff-resident interactions) involved in care for residents living with dementia may be one of the most critical components to reduce BPSD.6 Initially, rumors regarding the staffing changes spread to the extent that some night shift workers were afraid of losing their jobs. Within 2 days of becoming aware of these rumors, an in-service was conducted for all staff to allow them to share concerns and receive answers directly from the implementation team. The team also worked closely with the human resource manager to hire CNAs who were eager to embrace the concepts of culture change. Hiring and scheduling challenges occurred weeks before the implementation, and a close relationship and involvement with human resources was instrumental in the implementation process.

Program Evaluation and Outcomes

At baseline and 3 months after the QI intervention was implemented, the team conducted a review of paper and electronic medical records to evaluate for vital sign measurement, sedative and antipsychotic medication administration, and night medication administration. The change in mean number of blood pressure assessments per month was evaluated with a paired t-test. The mean number of blood pressure assessments per resident per month was significantly reduced in the month following the QI intervention, from a mean (SD) of 56.5 (34.7) assessments per resident per month to a post-intervention average of 6.9 (8.1) assessments per resident (P < .0001).

Because of the small sample size, change in the proportion of residents receiving antipsychotics was evaluated using Mantel-Haenszel chi-square analysis. The proportion of residents receiving antipsychotic medications was significantly reduced, from 18% to 5%, at 3 months after the QI intervention (P = .009). This decrease was not associated with any increase in the use of sedatives or anxiolytics; on the contrary there were more sedatives or anxiolytics reduced or stopped than those started or increased.

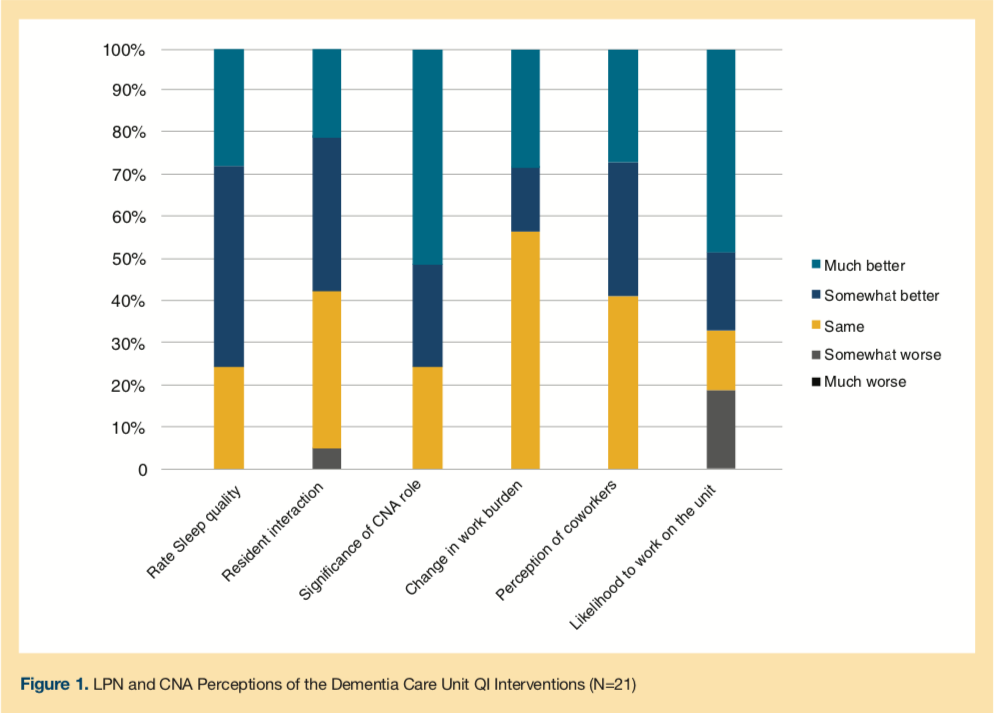

Unit nurses’ perceptions regarding the effects of the interventions were assessed at 3 months following the intervention period using a questionnaire. Responses were generally positive (Figure 1), with nearly 70% of staff reporting resident sleep quality was better or much better. More than half of the LPNs and CNAs felt that they had a much more significant role in the care of the residents. No staff member reported feeling that his or her role was less significant. Though 60% reported their job burden had not changed, the rest felt it was better or much better. Three-quarters of the nursing staff reported being more likely to work on the dementia care unit after implementation.

Discussion

This QI initiative, which involved an interdisciplinary approach to provide patient-centered care in a dementia care unit, was associated with a reduction in the proportion of residents receiving a prescription for antipsychotic medications for BPSD. Engaging staff in the process, strong facility and physician leadership, and reconfiguring staffing models and processes to promote elements of the culture change model for LTC were key components.

Because LTC residents living with dementia may lack the ability to clearly communicate preferences for care, it is more challenging to measure their satisfaction related to culture change initiatives. Indeed, there are limited data with respect to the impact of culture change as it relates to LTC dementia residents.7-9 The Restorative Care Intervention for the Cognitively Impaired, a program that operationalized principles of culture change as applied to ADLs in residents with moderate to severe dementia, did not yield any significant effect on disruptive behavior and had modest effect on agitation.10 Because validated measures for agitation and disruptive behavior are lacking in the LTC setting, some have suggested that a reduction in antipsychotic medication administration is a clinically relevant proxy to assess a program’s effectiveness.7,11

A subsequent qualitative study examined the experiences of nursing assistants that were involved with the Restorative Care study and identified the following barriers to implementation: resident factors (learned dependency, attention seeking through caregiving, severity of dementia); staff factors (lack of realization of residents’ abilities, lack of support from nursing supervisors); and family pressure to provide more care.12 In addition to these factors, which are common among LTC facilities, culture change implementation has been limited by the need for financial investment on the part of the facilities.13

There are limitations to this report. The intervention was developed in a single institution; however, the step-wise description of implementation and evaluation as well as challenges and solutions is intended to facilitate replication and adaptation for other facilities. It is possible that the change in proportion of antipsychotics prescribed after implementation of the QI program could be due to other factors beyond the QI program; however, the proximity of the observed changes to program implementation supports causality. Previous research suggests less extensive interventions focused solely on deprescribing also result in significant reduction in antipsychotic drug use.14,15

Conclusion

We present an approach to create a sustainable, patient-centered environment in a LTC dementia unit. Up to 3 months after implementation of the QI program, the proportion of residents receiving antipsychotic medications was significantly reduced. Additionally, nursing staff felt more satisfied with their jobs and reported reduced job burden, improved perception of their coworkers, and greater likelihood to work on the unit as a result of the changes. Strong facility leadership support and a PC with an engaged interdisciplinary team are factors that impact successful implementation and sustainability.

1. Maher A, Maglione M, Bagley S, et al. Efficacy and comparative effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic medications for off-label uses in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;306(12):1359-1369.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes. 2015. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/National-Partnership-to-Improve-Dementia-Care-in-Nursing-Homes.html. Accessed October 30, 2016.

3. Briesacher BA, Tjia J, Field T, Peterson D, Gurwitz JH. Antipsychotic use among nursing home residents. JAMA. 2013;309(5):440-442.

4. The Pioneer Network. What is Culture Change? 2015. Accessed October 30, 2016.

5. White-Chu EF, Graves WJ, Godfrey SM, Bonner A, Sloane P. Beyond the medical model: the culture change revolution in long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(6):370-378.

6. Mitchell JI, Long JC, Braithwaite J, Brodaty H. Social-professional networks in long-term care settings with people with dementia: an approach to better care? A systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(2):183.e117-183.e127.

7. Volicer L. Culture change for residents with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9(7):459.

8. Karel MJ, Teri L, McConnell E, Visnic S, Karlin BE. Effectiveness of expanded implementation of STAR-VA for managing dementia-related behaviors among veterans. The Gerontologist. 2016;56(1):126-134.

9. Richter T, Meyer G, Möhler R, Köpke S. Psychosocial interventions for reducing antipsychotic medication in care home residents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD008634. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008634.pub2.

10. Galik EM, Resnick B, Gruber-Baldini A, Nahm E-S, Pearson K, Pretzer-Aboff I. Pilot testing of the restorative care intervention for the cognitively impaired. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9(7):516-522.

11. Volicer L, Bass EA, Luther SL. Agitation and resistiveness to care are two separate behavioral syndromes of dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8(8):527-532.

12. Resnick B, Petzer-Aboff I, Galik E, et al. Barriers and benefits to implementing a restorative care intervention in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9(2):102-108.

13. Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ. 2015;350:h369.

14. van Reekum R, Clarke D, Conn D, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the discontinuation of long-term antipsychotics in dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(2):197-210.

15. Declercq T, Petrovic M, Azermai M, et al. Withdrawal versus continuation of chronic antipsychotic drugs for behavioural and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD007726. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007726.pub2.