A Quality Improvement Project with the Aim of Improving Suicide Prevention in Long-Term Care

Rates of suicide in long-term care (LTC) are high. To address this serious issue, a quality improvement project to improve suicide prevention in LTC was designed. The quality improvement project included two elements: an evidence-based suicide prevention gatekeeper training program for personnel, and a depression and suicide risk screening instrument for newly admitted residents. A pilot study to test the quality improvement strategy was done at one LTC facility in Montana, a state with a suicide rate that is among the highest in the United States. Nursing and allied health personnel (N = 43) completed the gatekeeper training program. Self-evaluative survey data suggested personnel benefited from the training. Of 89 newly admitted residents that completed the depression and suicide-risk screening assessment, 37 were identified as at risk for suicide and received follow-up services. Clinical leadership reported that the screening instrument was helpful for identifying residents who may be at higher risk of suicide and for initiating conversation with these residents. Lessons from the pilot project have implications for applying the quality improvement approach on a larger scale to reduce the high suicide rate among aging adults.

Key words: suicide prevention, gatekeeper training, evidence-based practice, quality improvement

Suicide is an international, public health problem that is only worsening. In the last 45 years, international rates of death due to suicide have increased to a current rate of 11.4 per 100,000 persons.1 In the United States, suicide is the 10th leading cause of death.2 In addition, US rates of suicide in long-term care (LTC) facilities can range anywhere from 16.5% to 34.8%.3,4 Obtaining accurate suicide statistics in LTC remains a challenge given manifestations of indirect self-destructive behaviors, such as refusals to eat or drink and medication non-compliance.5-7 It has been suggested that inclusion of indirect behaviors increases the suicide rate substantially to 94.9 per 100,000 persons.7,8 Of particular significance are members of the “baby boomer” generation, which had higher rates of suicide than other generations in their adolescent years.9,10

Close observation remains a central approach to caring for acutely suicidal patients in medical settings,11 psychiatric units,12 and LTC settings.4 Yet, up to 18% of those under close observation in psychiatric units commit suicide.12 Another intervention, the no-harm contract, lacks supporting evidence in preventing suicide; yet, it continues to be utilized in medical settings.7,12,13 Therefore, better strategies for managing LTC residents at risk for suicide are needed.

A quality improvement project was implemented to improve strategies for suicide prevention used at one LTC facility in central Montana. Incidentally, as of 2013, the State of Montana had the highest suicide rate in the United States at 23.7%.2 To design the approach for the quality improvement project, available evidence on suicide and suicide prevention strategies for LTC residents was examined through the Concordia University Wisconsin online library utilizing The Summon Service (ProQuest; Ann Arbor, MI). Using the search terms “suicide prevention” and “nursing homes” yielded 287 scholarly articles, which were examined as the basis for this quality improvement project.

Barriers to Managing Suicide Risk Among LTC Residents

The literature search revealed two primary barriers to managing suicide risk among LTC residents. The first is problematic attitudes, lack of knowledge, and insufficient skill among clinicians in identification and management of suicidal patients.11,14,15 In their descriptive study, Neville and Roan11 identified negative attitudes among medical-surgical nurses toward suicidal patients using the Attitudes Toward Attempted Suicide Questionnaire (ATAS-Q). The authors concluded further education on suicide risk assessment and remediation of attitudes were necessary for safe and effective care. Saunders and colleagues, in a systematic review of studies conducted in Australia, Brazil, Canada, Finland, Ireland, Malta, Norway, Sweden New Zealand, Zimbabwe, and the United States, identified hostility, frustration, helplessness, irritation, anger, and intolerance among clinicians toward suicidal patients.16 Similar findings regarding problematic attitudes, lack of knowledge, and perceived skill have been reported elsewhere in international literature.16-21 Additionally, it was found that nurses may fear litigation from saying something inappropriate or believe that talking about suicide causes a suicide.11 Nurses may defer suicide risk assessment due to perceived lack of skill11 or by believing that legal responsibility belongs to mental health specialists.11,12

The second major barrier to managing suicide risk among LTC residents is challenges in the identification and management of suicide risk among older adults7 and, in particular, LTC residents, for whom research has been limited.4 Depression is the most frequently reported psychiatric disorder in LTC6,22 and has been reported as a significant correlate of suicide in LTC. Yet, depression remains under-recognized and under-treated,23 and there is limited research regarding depression in LTC settings.6,24,25 As of 2010, fewer than 25% of depressed residents in LTC had been accurately identified.23 Hoover and colleagues,26 in their review of the Minimum Data Set of more than 600,000 residents admitted from 1999 to 2005 in 4216 facilities, concluded that the first 8 months of admission to a LTC facility are a particularly vulnerable time for residents.

Quality Improvement Strategy

Based on the two major barriers to suicide prevention in LTC that were identified in the literature search, a quality improvement strategy was designed that included two approaches. The first was an evidence-based suicide prevention gatekeeper training program for nursing and allied health personnel employed by the setting, and the second was the implementation of a depression and suicide-risk screening instrument for newly admitted residents.

Question-Persuade-Refer (QPR) Suicide Prevention Gatekeeper Training Program

Gatekeeper training is a brief, structured education program found to be effective for improving attitudes, knowledge, and skill among clinicians caring for suicidal patients. The term “gatekeeper” refers to those in front-line positions who encounter suicidal persons. Gatekeeper training has been implemented as stand-alone interventions and integrated into larger suicide prevention strategies. Many have proposed that it be instituted in health care settings.11,15-17, 27-35

The Question-Persuade-Refer (QPR) Suicide Prevention Gatekeeper Training is a three-step program on how to ask about suicidal thoughts and feelings, how to persuade the person to seek help, and how to refer to appropriate resources (www.qprinstitute.com).36 The program is 1 of 15 evidence-based suicide prevention programs listed online at the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices (NREPP).37 QPR was adopted by the State of Montana as part of a larger suicide prevention strategy.

Quality improvement projects or research studies utilizing evidence-based suicide prevention gatekeeper training as an intervention in LTC have not been previously reported. One US study did include LTC personnel among primary care physicians, nurses, counselors, and social workers (N = 446) in a quasi-experiment examining effects of suicide risk training and identified improved attitudes, knowledge, and confidence upon completion of training after four months.31 Another study explored the effects of an educational program on suicide among emergency department personnel in a Georgia hospital. The researchers used a convenience sample of 54 clinicians, including nurses and social workers. Pre- and post-test measures showed an increase in knowledge scores (from 7.9 to 13.6, P < .001) and self-efficacy scores (from 24.0 to 32.3, P < .001) on management of suicidal patients.15

An additional study involved the US Air Force’s incorporation of gatekeeper training in a multifaceted suicide prevention strategy. In the study, Knox and colleagues32 examined effects of the program on more than 5 million personnel between 1997 and 2002. A 33% relative risk reduction in suicide was identified after the intervention compared to previous years (P < 0.001 95% CI 0.57 to 0.80). Knox and researchers33 also re-examined findings from the previous cohort study,32 suggesting such training be incorporated into a community-based strategy. Gatekeeper training has been found to be effective in other settings as well, including crisis hotlines,38 health departments,39 colleges, and universities.40

In Taiwan, a randomized-controlled study of gatekeeper training was implemented for generalist and psychiatric nurses (N = 195).35 Researchers found improved attitudes toward suicidal persons, increased awareness and understanding of risk factors, and confidence in making referrals among those receiving gatekeeper training. Similar findings of brief training on suicide risk and suicide prevention were found in studies conducted in Brazil27,28 and the United Kingdom.29 England adopted STORM®, a nationwide skills-based suicide prevention program, found to improve attitudes, knowledge, and skill in identification and management of those at risk.30

Depression and Suicide-Risk Screening Instrument for Newly Admitted Residents

Older adults typically do not directly verbalize depressive symptoms or suicidal thoughts and feelings; therefore, additional approaches, such as use of screening instruments, are necessary.5,41 One of the most popular suicide screening tools for older adults is the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15),5 which allows personnel to determine which patients are at risk or have risk factors for depression. The GDS-15 is constructed in a “yes” or “no” format. On the GDS-15, a score > 5 is suggestive of depression and warrants follow-up assessment. A score of ≥ 10 is almost always indicative of depression.

There has been a limited amount of research examining use of the GDS-15 in LTC.42 Harris and Cooper43 examined depression among those on acute rehabilitation units in LTC. In their retrospective design, researchers utilized a random sample of 137,000 Medicare enrollees aged 65 and older. The question, “In the past year, have you felt sad or depressed much of the time?” was found to most closely correlate to a diagnosis of depression and recommended as a useful screening tool.43

Mitchell and colleagues42 examined 69 studies in a meta-analysis exploring diagnostic accuracy of the 30-item GDS, the 15-item GDS, and the ultra-short version of the GDS (4/5 items) in medical settings including LTC. The studies measured diagnostic validity of the GDS against semi-structured psychiatric interviews. The authors recommended the GDS-15 for use in LTC (sensitivity and specificity were 86.6% [95% CI, 76.1–94.4] and 72.3% [95% CI, 50.6–89.6], respectively).42

Heisel and colleagues44 found the GDS-15 a useful screen for older adults at risk for suicide in a sample of 105 of those 65 years of age and older recruited from LTC settings, community-based seniors’ programs, and medical and psychiatric inpatient and outpatient practices. The GDS-15 has been used to identify those in LTC who retain a sense of hopelessness, a key feature of older adults at risk for suicide.7,42 The GDS-15 includes five items assessing suicide ideation: (1) “Do you feel that your life is empty?; (2) Do you feel happy most of the time?; (3) Do you think it is wonderful to be alive?; (4) Do you feel pretty worthless the way you are now?; and (5) Do you feel that your situation is hopeless? Heisel and colleagues41 found that the GDS-15 with its 5-item suicide ideation subscale accurately identified older adults with suicide ideation among 626 older adults in primary care. Cheng and colleagues45 also found the GDS-15 version an acceptable tool for detecting suicide ideation in their sample of older adults.

Based on these studies, the screening instrument used in this quality improvement project primarily consisted of the GDS-15.36 However, a major risk factor for suicide identified in our literature search that is not addressed in the GDS-15 is being a “suicide survivor,” defined as one who has experienced the loss of a significant other to suicide.46,47 Suicide is said to create a “heavy load” of guilt and grief for those left behind.46 A family history of suicide has been found to increase the risk of suicide attempts and completed suicide.46,47 McMenamy and colleagues47 reported depression, anxiety, sleep problems, anger, and irritability among 63 adult suicide survivors. The authors asserted that talking about their experiences is necessary for survivors’ recovery.47 Crosby and Sacks48 revealed that 342 of 5238 respondents whose loved one committed suicide within the preceding 12 months were more likely to report suicidal thoughts, plans, and attempts as compared to those who had not experienced such a loss, concluding that exposure to suicide may be an important question to pose as part of any suicide risk assessment. The National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action echoes these findings, delineating suicide survivors as a high-risk group in need of identification and remediation.49

Based on these findings, two additional items were added to the screening instrument: (1) “In the past year, have you felt sad or depressed much of the time?”;43 and (2) “Has a family member or close friend completed suicide?”46

Pilot Study of the Quality Improvement Approach

The objective of the pilot study for the quality improvement project was to examine staff feedback following the implementation of the gatekeeping training and the screening tool to determine the success of these suicide prevention strategies in an LTC setting.

Setting

From February 2014 to September 2014, the pilot project was conducted over a 6-month period in a for-profit, 150-bed LTC facility with one acute rehabilitation unit and three LTC units, located in central Montana, the state which, incidentally, as of 2013, has the highest suicide rate in the United States at 23.7%.2 Approximately 92% of residents were white, and the remainder were of other ethnicities, including Native Americans and African Americans. The setting was chosen because of the intention of leadership to offer training on suicide prevention and because the topic of suicide prevention training was identified to be of interest to personnel. Personnel reportedly asked for factual information on suicide and expressed a desire for greater comfort and confidence in asking residents about suicidal thoughts and feelings. The project received institutional review board approval from Concordia University Wisconsin, where the author was a student completing a DNP program at the time of the study, because the LTC setting did not have an institutional review board.

QPR Suicide Prevention Gatekeeper Training

The QPR Suicide Prevention Gatekeeper Training was implemented without incurring any costs to personnel or to the setting. The accompanying QPR booklets were donated by the state’s Office of the Suicide Prevention Coordinator. The setting’s stakeholders were aware QPR Suicide Prevention Gatekeeper Training was available without cost through a local suicide prevention coalition comprised of nurses, counselors, and social workers who are volunteer-certified QPR instructors.

The leadership announced in staff meetings QPR training would be available for the convenience of personnel (before and after shifts), and those who chose to participate could receive gatekeeper certification. No personnel employed by the setting were excluded from the training sessions. Inclusion criteria for participation in the gatekeeper training program were those in the nursing field and other personnel who were either part- or full-time employees at the LTC facilities.

Prior to the beginning of each QPR, participants were reminded that training was voluntary and they could leave at any time. The training was provided face-to-face by one volunteer, a certified QPR instructor from the county suicide prevention coalition who is a geriatric nurse practitioner known to the setting. The training required a minimum 2-hour time commitment. Sixteen QPR sessions were scheduled during the 6-month project timeframe upon recommendation of the director of nursing based upon personnel convenience.

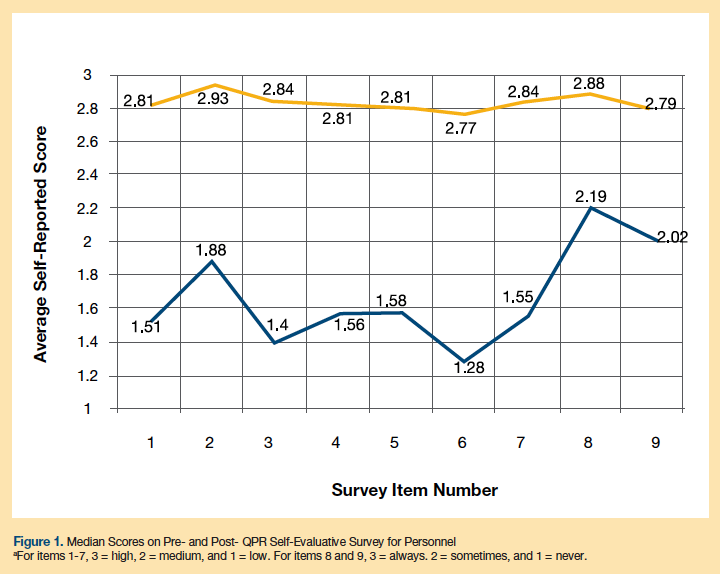

Accompanying the QPR instructional materials was a 9-item self-evaluative survey. The first 7 items were: 1) facts concerning suicide prevention, 2) warning signs of suicide, 3) how to ask someone about suicide, 4) persuading someone to get help, 5) how to get help for someone, 6) information about local resources, and 7) level of understanding. Participants are asked to complete surveys anonymously at pre- and post-training, evaluating themselves (“low,” “medium,” or “high”) on the first 7 items. The survey asks participants 2 additional questions: “How often do you feel that asking someone about suicide is appropriate?” and “How often do you feel likely to ask someone if they are thinking of suicide?” The response options were “always,” “sometimes,” or “never.” The demographic portion of the pre- and post-training survey was adapted with permission. All participants completed the 9-item survey at pre- and post-training. Each participant’s pre-training responses were compared to post-training responses. Analysis of quantitative data was completed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 22.

Participants were also asked to complete the anonymous Attitudes Toward Suicide Prevention Scale (ATSPS),18 a 14-item, self-rated, 5-point Likert scale, from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” prior to the QPR training. Participants were asked to reflect upon their responses to the ATSPS and invited to discuss them at the end of the project timeframe at an open forum to provide feedback about the project experience and how their own attitudes about suicide prevention may or may not have changed. The ATSPS had acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha, .77) and high test re-test reliability, with a correlation coefficient of .85 (P < .001).18 Participants were invited to retain completed instruments. Permission for use was obtained from the author.

Of the 16 scheduled sessions, 11 were attended. Of 85 personnel eligible to participate, 43 (51%) attended. Among the 43 participants, 4 (9%) were male and 39 (91%) female. Ages ranged from 22 years to 72 years (mean age, 44.8 years). Of the participants, 38 were white (88%), 3 were Hispanic (7%), 1 was Asian American (2%), and 1 was Native American (2%). Among occupations, 65% of participants were in nursing. There were 8 registered nurses, 10 licensed practical nurses, 10 certified nursing assistants, 2 social workers, 2 physical therapists, 1 occupational therapist, 1 speech therapist, and 2 therapy aides. There were 7 participants who indicated “other” occupations, some of whom identified themselves as nutritionists or in human resources. Participants’ work experiences varied: 11 (25%) had less than 5 years of experience; 4 (9%) had 5 to 10 years of experience; 6 (14%) had 10 to 15 years of experience; 5 (12%) had 15 to 20 years of experience; and 17 (40%) had more than 20 years of experience.

Depression and Suicide-Risk Screening Instrument for Newly Admitted Residents

The lead social worker at the study site volunteered to incorporate the depression and suicide-risk screening instrument, consisting of the GDS-15 plus the two additional questions, into the new resident admission process. The criteria for use of the GDS-15, as established by its authors,36 were followed. Primary care physicians were notified of those residents who scored 10 or more on the GDS. A “yes” response to either of the 2 additional items warranted follow-up assessment. Follow-up assessments were provided by the master’s prepared social worker, with results presented at treatment team meetings, facilitating further follow-up by nursing personnel on the units. Nursing and other personnel trained in QPR were encouraged by clinical leadership to provide ongoing follow-up assessment and therapeutic dialogue.

Pilot Study Outcomes: QPR Survey Responses

Each participant’s pre-training responses were compared to post-training responses. A median difference in pre- and post-training scores was determined for each item indicating higher scores at post-training (Figure 1). Among participants, 32 (74%) evaluated the training as excellent, 6 (14%) as very good, 5 (12%) did not respond, and 100% recommended the training.

The self-reports of an improved fund of knowledge in identification of those at risk for suicide following the QPR training was consistent with studies utilizing educational interventions.15,27,29-31,33,35,38-40 Participants reported that the QPR training increased their awareness regarding the higher risk status of those newly admitted to LTC. Similar findings have been reported.6,26,27,29,31,33,35,43

Twenty-one participants completed the comment section at post-training. General comments of QPR being informative and helpful emerged. Three participants commented they felt more “comfortable” about asking patients about being at risk for suicide. Another participant stated the training increased “confidence” in asking residents about suicidal thoughts or feelings.

Pilot Study Outcomes: Suicide Risk Screening

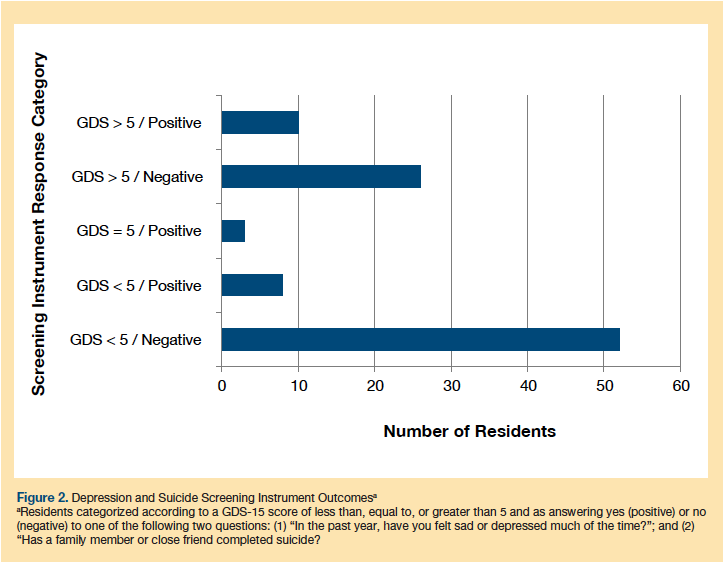

Upon admission to LTC, 89 out of 91 residents completed the screening instrument (Figure 2). Among them, 52 residents scored less than 5 on the GDS-15 and did not endorse having a depressed mood or a significant other who committed suicide. Their scores suggested no further follow-up was indicated. The remaining 37 residents had scores of 5, < 5, or > 5 on the GDS-15, and/or endorsed the remaining two items regarding feeling sad or depressed or having a significant other who committed suicide, suggesting further follow-up was indicated. A total of 26 residents scored > 5 on the GDS. Of these, 16 residents did not endorse having a depressed mood or significant other who committed suicide. Seven residents indicated they had a depressed mood, 2 residents reported significant others who committed suicide, and 1 resident endorsed both depressed mood and having a significant other who committed suicide. A total of 3 residents scored 5 on the GDS. All 3 endorsed having a depressed mood or a significant other who committed suicide. A total of 8 residents scored < 5; of those, 2 residents indicated having a depressed mood much of the time, and the other 6 endorsed having a significant other who committed suicide. The 37 residents received further follow-up assessment by the lead social worker during admission and later by social workers and nursing staff on the units. All 37 residents were offered appointments with either a primary care physician or psychiatrist by the lead social worker, and only 2 accepted those appointments.

Pilot Study Outcomes: Open Forum to Invite Participant Feedback

Concluding the project was an open forum for participants to discuss possible changes in self-reported attitudes, knowledge, or skill regarding suicide prevention. Fifteen individuals who completed training attended and discussed their experience of the training and screening tool.

It has been suggested that attitudes may adversely impact a clinician’s ability to properly assess suicidal individuals.18 Participants at the open forum made reflective comments with regard to item two of the ATSPS: “Suicide prevention is not my responsibility.” Participants stated they now felt identifying and managing those at risk for suicide was within their domain of professional responsibility. This was consistent with previous findings that clinicians may believe the domain of responsibility for suicide assessment resides elsewhere.11,12,18 Self-reported participant responses indicate a change in their comfort level, as reflected by item 11 on the ATSPS: “I don’t feel comfortable assessing someone for suicide risk.” Participants stated they developed an increased comfort level asking about suicide risk, consistent with previous findings.18,27-30,35,39,40 These responses suggest that completing the ATSPS may have increased participants’ self-awareness of attitudes that prevented adequate management of residents at risk of suicide.

The LTC setting’s leaders reported that the pilot quality improvement project addressed an expressed knowledge and skill need among personnel. It was their opinion that the QPR training and the screening instrument helped increase both comfort and confidence among personnel asking residents about suicidal thoughts and feelings. They observed nursing personnel who completed the QPR sessions engaged in more frequent therapeutic communication with residents about their lived experiences with depression or suicide.

The lead social worker found that during routine admission procedures, the GDS-15, plus the two additional items, facilitated dialogue with residents about their lived experiences with depression or suicide and that this dialogue continued on the units with nursing personnel. The lead social worker also reported that the last question regarding the loss of a significant other to suicide, in one case, led to a 2-hour conversation with a resident who reported to have never previously talked about the family member’s suicide. Allowing residents to talk about thoughts and feelings has been deemed necessary to move suicidal individuals from a “death-oriented” position to a “life-oriented” position, as discussed by Cutcliffe and Stevenson.12

Limitations

There were limitations to this pilot quality improvement project. First, outcomes of a project should be generalized with caution. Second, approximately half of the setting’s personnel have not completed QPR training. It has been suggested that provision of continuing education units, or paid attendance, would ensure greater numbers of participants. Third, no pre-intervention data were collected. Finally, it was not determined whether the training, the screening instrument, or the combination of the two affected the identification and management of residents at risk for suicide.

Conclusion

The proposed quality improvement strategy to improve suicide prevention in a LTC setting encompassed two elements. First was the provision of QPR, an evidence-based suicide prevention gatekeeper training program for personnel. Second was administration of a 17-item screening instrument (GDS-15 plus 2 additional items) for newly admitted residents. In a pilot study to test the quality improvement approach, participant self-evaluations stated that they benefited from the program, and, of the 89 residents who completed the suicide risk screening, 37 (42%) were identified as at risk of suicide and received follow-up by personnel for suicide risk. Overall, outcomes suggested that the pilot quality improvement project mirrored previous positive results with the gatekeeper training program, but in an LTC setting.

Implementation of the project generated interest among personnel, including administrative and clinical leadership, from the beginning. The setting’s leadership reported the project appeared to increase dialogue about suicide prevention among personnel who participated in the training as observed in treatment team reports and on units. In turn, this generated therapeutic communication with residents about their own lived experiences with depression or suicide. It was their assessment that such a project may increase clinician comfort and confidence when asking residents about suicide, thereby normalizing such questions in an assessment. These findings could pave the way for examination of such interventions as a practice change initiative.

Replication of the pilot quality improvement project depends partly on organizational needs, interest on the part of personnel, including administrative and clinical leadership, and suitability of an educational program for the chosen setting. A starting place might begin with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website (www.samhsa.gov). Promoting Emotional Health and Preventing Suicide: A Toolkit for Senior Living Communities is available free, and includes helpful information including risk factors, warning signs, and case studies. Another is the NREPP website for various suicide prevention programs and practices which differ in target audience, cost, and time commitment. The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention website provides state chapter listings and suicide prevention resources which are helpful in considering a similar project. And lastly, an invaluable resource is 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action published by the Department of Health and Human Services available without cost (www.samhsa.gov/nssp).

1. World Health Organization. Mental health suicide prevention SUPRE. WHO Web site. http://www.who.int/gho/mental_health/suicide_rates/en/. Accessed July 20, 2014.

2. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Facts and Figures. AFSP Web site. https://www.afsp.org/understanding-suicide/facts-and-figures. Accessed July 20, 2014.

3. Mezuk B, Prescott, MR, Tardiff, K, Vlahov D, Galea S. Suicide in older adults in long-term care: 1990-2005. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(11):2107-2111.

4. O’Riley A, Nadorff MR, Conwell, Y, Edelstein B. Challenges associated with managing suicide risk in long-term care facilities. Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging. 2013;21(6):28-34.

5. Fitzpatrick JJ. Signs of silent suicide among depressed hospitalized geriatric patients. J Am Psychiatr Assoc. 2005;11(5):290-292.

6. Podgorski, CA, Langford L, Pearson, JL, Conwell Y. Suicide prevention for older adults in residential communities: implications for policy and practice. PLoS Medicine. 2010;7(5):e1000254. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000254

7. Szanto, K, Gildengers A, Mulsant BH, Brown G, Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF III. Identification of suicidal ideation and prevention of suicidal behaviour in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2002;19(1):1-24.

8. Osgood N, Brant B. Suicidal behavior in long-term care facilities. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1990;20(2):113-122.

9. Conwell Y, Van Orden K, Caine ED. Suicide in older adults. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011;34(2):451-468.

10. Phillips JA, Robin AV, Nugent CN, Idler EL. Understanding recent changes in suicide rates among the middle-aged: period or cohort effects? Public Health Rep. 2010;125(5): 680-688.

11. Neville K, Roan NM. Suicide in hospitalized medical-surgical patients exploring nurses’ attitudes. J Psychosoc Nurs. 2013;51(1):35-43.

12. Cutcliffe JR, Stevenson C. Feeling our way in the dark: The psychiatric nursing care of suicidal people-a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(6):942-953.

13. Lynch MA, Howard PB, El-Mallakh P, Matthews JM. Assessment and management of hospitalized suicidal patients. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2008;46(7):45-52.

14. Bern-Klug M, Kramer KW, Sharr P. Depression screening in nursing homes: involvement of social services departments. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(3):266-275.

15. Shim RS, Compton MT. Pilot testing and preliminary evaluation of a suicide prevention education program for emergency department personnel. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46(6):585-590.

16. Saunders KE, Hawton K, Fortune S, Farrell S. Attitudes and knowledge of clinical staff regarding people who self-harm: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012;139(3):205-216.

17. Brunero S, Smith J, Bates E, Fairbrother G. Health professionals’ attitudes towards suicide prevention initiatives. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008;15(7):588-594.

18. Herron J, Tigehurst H, Appleby L, Perry A, Cordingley L. Attitudes toward suicide prevention in front-line health staff. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;31(3):342-347.

19. Keogh B, Doyle L, Morrissey J. Suicidal behavior: a study of emergency nurses’ educational needs when caring for this patient group. Emerg Nurs. 2007;15(3):30-35.

20. Kishi Y, Kurosawa H, Morimura H, Hatta K, Thurber S. Attitudes of Japanese nursing personnel toward patient who have attempted suicide. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(4):393-397.

21. Osafo J, Knizek BL, Akotia CS, Hjelmeland H. Attitudes of psychologists and nurses toward suicide and suicide prevention in Ghana: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(6):691-700.

22. Huang Y, Carpenter I. Identifying elder depression using the Depression Rating Scale as part of a comprehensive standardized care assessment in nursing homes. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(8):1045-1051.

23. Snowdon J. Depression in nursing homes. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(7):1143-1148.

24. Mezuk B, Rock A, Lohman MC, Choi M. Suicide risk in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29:1198-1211.

25. Suominen K, Henriksson M, Isometsä E, Conwell Y, Heilä H, Lönnqvist J. Nursing home suicides-a psychological autopsy. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(12):1095-1101.

26. Hoover DR, Siegel M, Lucas J, et al. Depression in the first year of stay for elderly long-term nursing home residents in the USA. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(7):1161-1171.

27. Berlim MT, Perizzolo J, Lejderman F, Fleck MP, Joiner TE. Does a brief training on suicide prevention among general hospital personnel impact their baseline attitudes towards suicidal behavior? J Affect Disord. 2007;100(1-3):233-239.

28. Botega NJ, Silva SV, Reginato DG, et al. Maintained attitudinal changes in nursing personnel after a brief training on suicide prevention. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2007;32(2):145-153.

29. Fenwick CD, Vassilas CA, Carter H, Haque MS. Training health professionals in the recognition, assessment and management of suicide risk. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2004;8(2):117-121.

30. Green G, Gask L. The development, research and implementation of STORM (Skills-based Training on Risk Management). Primary Care Ment Health. 2005;3(3):207-213.

31. Jacobson JM, Osteen P, Jones A, Berman A. Evaluation of the recognizing and responding to suicide risk training. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2012;42(5):471-485.

32. Knox KL, Littis DA, Talcott GW, Feig JC, Caine ED. Risk of suicide and related adverse outcomes after exposure to a suicide prevention programme in the US Air Force: Cohort study. BMJ. 2003;372(7428):1376-1380.

33. Knox KL, Pflanz S, Talcott GW, et al. The US Air Force Suicide Prevention Program: Implications for public health policy. Am J Pub Health. 2010;100(12):2457-2463.

34. Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review. JAMA. 2005;294(16):2064-2074.

35. Tsai W-P, Lin L-Y, Chang H-C, Yu LS, Chou MC. The effects of gatekeeper suicide- awareness program for nursing personnel. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2011;47(3):117-125.

36. Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5(1-2):165-174.

37. Quinnett P. Question, persuade, refer for suicide prevention: Certified QPR gatekeeper instruction manual. Spokane, WA: QPR Institute; 1995.

38. Gould MS, Cross W, Pisani AR, Munfakh JL, Kleinman M. Impact of Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training on the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2013;43(6):676-691.

39. Keller DP, Schut L, Pruddy RW et al. Tennessee lives count: Statewide prevention training for youth suicide prevention. Professional Psychol Res Pract. 2009;40(2):126-133.

40. Cross W, Matthieu MM, Lezine D, Knox KL. Does a brief suicide prevention gatekeeper training program enhance observed skills? J Crisis Intervention Suicide Prev. 2010;31(3):149-159.

41. Heisel MJ, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM, Feldman MD. Screening for suicidal ideation among older primary care patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(2):260-269.

42. Mitchell AJ, Bird V, Rizzo M, Meader N. Which version of the Geriatric Depression Scale is most useful in medical settings and nursing homes? Diagnostic validity meta-analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(12):1066-1077.

43. Harris Y, Cooper JK. Depressive symptoms in older people predict nursing home admission. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(4):593-597.

44. Heisel MJ, Flett GL, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM. Does the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) distinguish between older adults with high versus low levels of suicidal ideation? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(10):876-883.

45. Cheng ST, Yu EC, Lee SY, et al. The geriatric depression scale as a screening tool for depression and suicidal ideation: a replication and extention. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(3):256-265.

46. Krysinska KE. Loss by suicide a risk factor for suicidal behavior. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2003;41(7):34-41.

47. McMenamy JM, Jordan JR, Mitchell A. What do suicide survivors tell us they need? Results of a pilot study. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38(4):375-389.

48. Crosby AE, Sacks JJ. Exposure to suicide: Incidence and association with suicidal ideation and behavior: United States 1994. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2002;32(3):321-328.

49. US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: Goals and Objectives for Action. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2012.