Providing Palliative Care Across the Continuum to Reduce Readmissions From Community Settings

Abstract: Patients at the end of life often experience unwanted transitions of care. We describe a pilot project aimed at improving transitions of care and reducing hospital readmissions for patients receiving an inpatient palliative care consult at one hospital. A transition team was created to track each patient’s discharge disposition over the course of 12 months, from January 1, 2016 to December 31, 2016, and any hospital readmission within 30 days of discharge. Frequent readmissions were identified for all patients, but special attention was paid to those discharged to a skilled nursing facility. Partnering with our health system’s community palliative care team allowed us to extend palliative care into partner facilities via a palliative nurse trained in communication skills to facilitate the transition of patients to hospice or community-based palliative care services as appropriate. Over the course of this yearlong project, readmission rates for all palliative care patients decreased from 22% to 16%. In particular, readmission rates of patients being discharged to partner facilities decreased from 26% to 10%. This pilot project demonstrates an opportunity for collaboration between inpatient palliative care teams and community partners in order to improve care transitions and reduce hospital readmissions in this subset of patients.

Key words: Quality improvement, transitions of care, palliative care

As we move into the era of value-based medicine, providing efficient, patient-centered care across the continuum of health care is becoming more important, not only from a quality perspective, but also from a financial perspective.1 While all patients can benefit from improved transitions of care, older patients with frailty and serious illness stand to gain the most.2,3 The current health care system is fragmented,2 often resulting in increased numbers of care transitions as patients approach the end of their lives.4

It is imperative that patients’ medical treatment aligns with their goals. Engaging with patients about what matters most can lead to higher-quality health care. Studies have demonstrated that patients who are seen by an inpatient palliative care team have a reduced number of readmissions5,6 and that palliative care consultations in nursing homes can reduce the chance of hospitalization in the last 30 days of life.7,8 One likely reason for this decrease in both settings is early appropriate transition to hospice as a result of a clear understanding of a patient’s goals.7

As part of the 2016 Practice Change Leaders for Aging and Health program, with grant funding provided by the John A. Hartford Foundation and the Atlantic Philanthropies, we undertook a project that facilitated closer collaboration between a hospital and its community partners with the use of an inpatient palliative care team. The ultimate aim was to improve transitions of care for all patients receiving palliative care after discharge from the hospital, with a focus on those discharged to an skilled nursing facility (SNF).

Care Settings and Intervention Teams

The project was conducted from January 1, 2016 through December 31, 2016 at Kent Hospital and four preferred SNFs within the Care New England Health System in Warwick, RI. The Care New England palliative care program consists of multidisciplinary inpatient consult services at four acute care facilities, a hospice team, and a variety of community based palliative care offerings, including collaborative management of complex medical patients within our health system’s accountable care organization (ACO).

The inpatient team consists of physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), and palliative care-trained and hospice-trained nurses who are proficient in conversation skills and are referred to as conversation nurses.9 The conversation nurses are employed by our community-based palliative care and hospice team but are housed in the inpatient setting. They are hospice trained nurses who have received additional education in communication skills to have conversations about goals of care. It is through this partnership with our system’s community-based palliative programs that we are able to provide care across care settings and sustain this position.

In addition to the inpatient team, the community-based palliative care services include complex patient case conferencing, a palliative care team, and an NP home-visit program. During case conferencing, the cases of patients with complex needs are discussed in a formal conference between the primary home care nurse and a palliative care NP: the NP trains the nurse in palliative care skills and identifies whether patients could benefit from more intense palliative care intervention. The palliative care team is either for patients who are hospice-appropriate but who are still receiving treatment-focused care, or for patients with an anticipated decline who will be appropriate for hospice within 8 weeks. The nurses who care for this group of patients are trained in palliative care and hospice care. The NP home-visit program provides complex medical management to patients with advanced illness who are frail with chronic comorbidities and who require symptom management and ongoing conversations about goals of care.

Preliminary data obtained from October to December 2015, prior to the start of this project, indicated that, for some patients, a palliative care consult while at the hospital resulted in a reduction in the number of readmissions. Data obtained from the Crimson data analytics tool, which categorizes severity of illness, identified patients with a diagnosis-related group-based risk score listed as “severe illness.” The data showed a 14% readmission rate for patients seen by palliative care compared with a 19% readmission rate for similar patients who were not seen by palliative care. Given the proprietary nature of the analytics tool, we were not able to examine these data more closely to determine which interventions might be leading to a reduction in readmissions. However, we suspected that palliative care was effectively linking patients with serious illness to community-based palliative services and referring them to hospice when appropriate. Based on this information, we designed a project to track all patients seen by the inpatient palliative care team for 30 days after discharge and to work with community-based partners to ensure a smoother transition of patients to postacute services.

Project Design and Implementation

In an effort to improve communication between SNF providers and community providers, a transition team led by an NP certified in palliative care was established. Weekly meetings were scheduled and consisted of inpatient and community-based clinicians, including a palliative care physician, NPs, and nurses. The case of each patient seen by the inpatient palliative care team at Kent Hospital during the yearlong project was tracked.

Data collection on each patient included demographics; admission date and discharge date; diagnosis; discharge location; community services provided; medical orders for life-sustaining treatment (MOLST); and readmission rates for each patient within 30 days of discharge. Much of the data needed to be collected manually, since the inpatient electronic medical record (EMR) and the community EMR did not communicate. In an early review of the preliminary data (October-December 2015) and first-quarter data (January-March 2016), a number of significant gaps were identified. Inconsistencies were found between patients’ discharge location documented in the inpatient EMR and the actual discharge location. For example, a patient might be listed as having gone home with palliative care services, but poor communication during the transition meant that the patient had been referred to traditional home health care instead. The transition team reviewed the discharge disposition for each patient to ensure that the patient transitioned to the appropriate level of care with the appropriate resources. In addition, patients at high risk for uncontrolled symptoms were identified, and next-day home health visits by a nurse or an NP were coordinated.

Additionally, to ensure that patients’ health care wishes were documented and communicated across care settings, collaboration with our informatics department was essential. We developed a new process to label palliative care notes for easier identification and retrieval. SNF palliative care visits were documented in the inpatient EMR so that if a patient were readmitted, clinicians would have access to the most recent conversations about goals of care. Routine meetings with the care management department led to improved documentation by identifying patients seen by palliative care within the discharge narrative, which then linked patients to community-based palliative care programs more efficiently. Palliative care consult and progress notes were shared with every discharge location by way of view-only access to the inpatient EMR. We worked closely with our medical records department to have completed MOLST forms scanned and uploaded into the EMR in real time. In addition, we established a new process with our system’s home-health agency to send biweekly discharge emails to identified members of the intake and palliative care departments with the most up-to-date patient discharge data to ensure timely home visits, and to share documentation of most recent goals-of-care conversations and symptom management regimens for the home care admission nurse.

In Quarter 1 (January-March 2016), 53% of patients seen by palliative care were discharged to an SNF for skilled services and readmitted within 30 days. Given the high number of patients in this group, we decided that the development of a specialized intervention would be appropriate. It became clear that the facilities needed additional resources in palliative care to support them in caring for complex patient cases. In collaboration with our regional quality improvement organization, Healthcentric Advisors, we approached the four local SNFs with the aim of developing a collaborative partnership and developed an additional intervention extending the conversation nurse into the SNF to continue goals-of-care conversations with patients discharged from Kent Hospital after receiving a palliative care consult. These nurses had only been used in inpatient facilities prior to this project; however, an opportunity was identified to expand this model into the community.

The conversation nurse (one conversation nurse responsible for all four SNFs) started seeing patients at SNFs on April 1, 2016. The conversation nurse was notified by a member of the transition team when any patient was discharged to one of the four partner facilities. As an active member of our inpatient palliative care team, the conversation nurse was familiar with the patients based on interdisciplinary rounds and had full access to the EMR and to the clinicians who treated the patient in the inpatient setting. The four partner facilities agreed to facilitate the conversation nurse in seeing any patient who had been seen by the inpatient team as a continuation of palliative care without requiring a separate physician order once the patient had reached the SNF. The conversation nurse would see patients at the SNF within 1 week of discharge.

After her initial visit, the conversation nurse would see the patients as often as clinically indicated, usually 1 to 3 times over the next 30 days. She notified the transition team if a MOLST had been filled out for a patient, or if that patient had transitioned to home-based palliative care or hospice services. Each patient’s EMR was reviewed to see whether the patient had been readmitted, transitioned to another level of care, or died during that 30-day period. This information was tracked in a spreadsheet and communicated to all members of the transition team. In addition to her responsibilities working with the inpatient palliative care team, the conversation nurse saw patients in the partner SNFs 2 days a week from April 2016 to October 2016.

Results

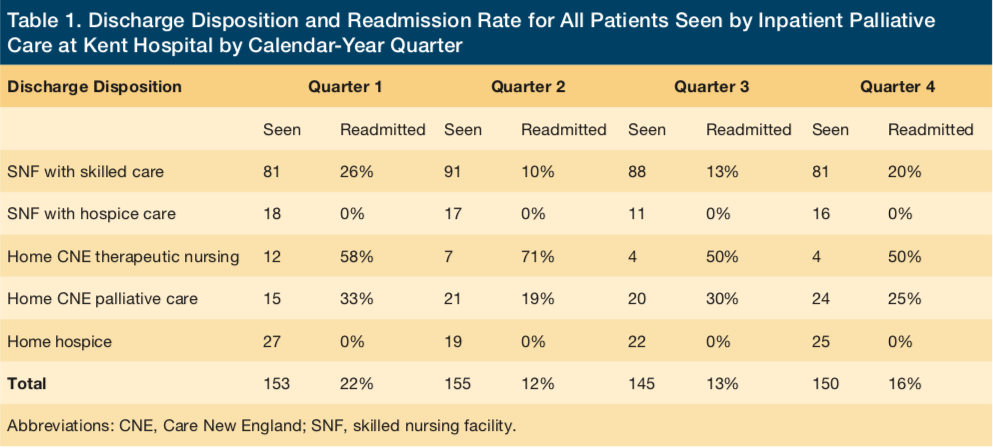

Over the course of this study, 896 patients were discharged and tracked after consultation by inpatient palliative care. Table 1 shows the discharge location and readmission rate for all patients, divided into 3-month quarters. During the first quarter, the transition team model was developed and provided baseline data. During the second and third quarters, the conversation nurse was introduced. During the fourth quarter, the transition team continued to function, but the conversation nurse was only available to see limited patients in November and December.

Discharge data were collected on all patients who received a palliative care consult (N = 896). Table 1 does not include discharge dispositions to home with no services, to home with home care agencies outside our health system, or hospital transfers, due to the fact that we did not provide any postacute intervention to this population. Readmission rates decreased for patients discharged to any location after the implementation of the transition team. Over the course of the project, we intentionally shifted patient referrals to more appropriate palliative care services, creating a decrease in the number of patients referred to therapeutic visiting nurse services and an increase in the number of patients referred to home-based palliative care.

Article continues on page 2

Review of the records of patients seen by the inpatient palliative care consult service and discharged from Kent Hospital during quarter 1 indicated that all patients discharged to nonhospice services had a high risk of being readmitted within 30 days. Analysis of first-quarter data found that of the patients discharged to a SNF for skilled services, 26% had been readmitted to the hospital. None of the patients discharged to an SNF for hospice services had been readmitted.

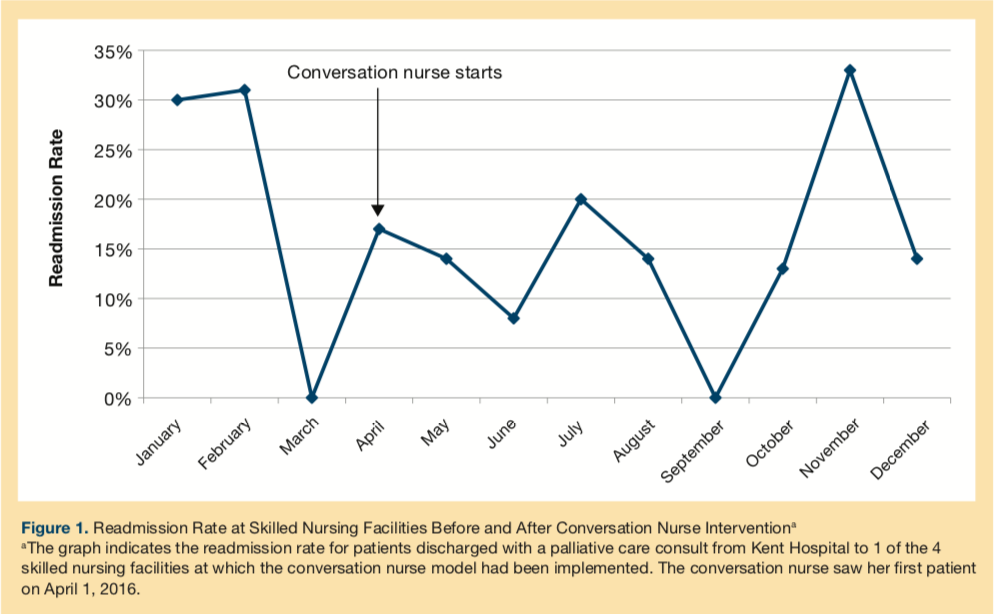

At the beginning of quarter 2, the conversation nurse started seeing patients in the SNFs. Figure 1 shows the readmission rate of patients seen by inpatient palliative care at Kent Hospital and discharged to one of the four partner facilities. There was a sustained decrease in readmissions after the conversation nurse began seeing patients—to 10% and 13% in quarters 2 and 3, respectively. Based on the value to the system that these data have revealed, the transition team continues to date. The eventual increase in readmission rate, seen in Figure 1, was correlated with the conflicting clinical responsibilities of the conversation nurse, which limited her ability to follow patients consistently after discharge in the months of November and December 2016.

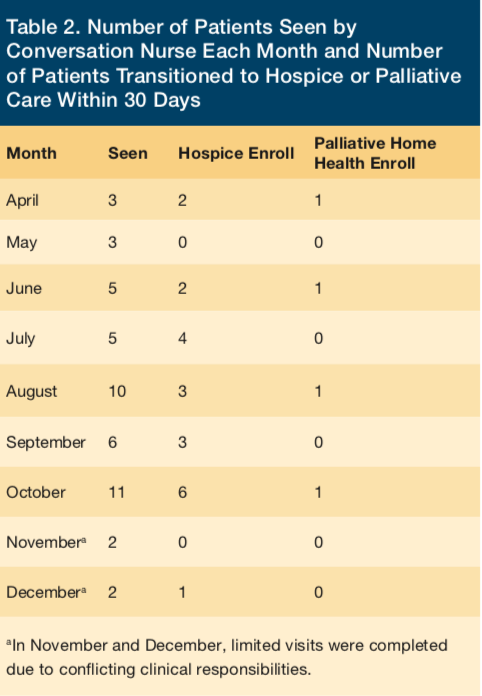

The number of patients seen by the conversation nurse each month, as well as the number of patients who transitioned to hospice or home-based palliative care, are shown in Table 2. The number of patients seen by the conversation nurse each month increased over the course of this initiative. Initially, we did not have the conversation nurse seeing patients followed by our health system’s ACO; however, after we demonstrated a reduction in readmissions, the ACO team asked us to follow their patients’ cases as well. Over the course of this project, the conversation nurse saw 47 patients, 45% of whom enrolled in hospice and an additional 9% of whom enrolled in palliative home services. Finally, 50% of these patients completed a MOLST form as a result of conversations about their treatment wishes at the end of life.

Discussion

In order to improve transitions of care for patients seen by the inpatient palliative care team at a community-based hospital, a process was developed to track all patients from the inpatient setting into the community setting and enhance communication between inpatient providers and community-based providers. In addition, we developed processes to ensure appropriate referral and placement of palliative care patients onto home-based palliative care services. We identified patients at high risk for symptom management needs and re-hospitalization, and we coordinated next-day visits, case conferencing, and NP management of symptom needs and complex goals of care. Through our weekly transition team meeting, we better aligned patients’ level of services to support their goals of care. As a result, we identified a decrease in readmission rates for all patients seen by the inpatient palliative care team.

Discharges to the home setting were identified as being to home with therapeutic nursing, to home with palliative care, and to home with hospice care. Through the transition team intervention, patients who were appropriate for palliative home care were realigned to the palliative care team, resulting in a reduction in the number of patients being discharged home with therapeutic nursing services. A high percentage (58%) of patients being sent home with therapeutic nursing services were readmitted. Readmission rates for this population seemed to be related to the complex needs of the patients who had progressive illnesses with changing health care needs and to the therapeutic nurses’ lack of specialized training in goals-of-care conversations and symptom management. The transition team reviewed every readmission to identify the cause. Most common causes for readmission were symptom management needs in the setting of advanced illness and unclear goals of care. Therapeutic nurses did not have the skill set to manage the complexities of this patient population, identifying the need for specialized palliative care services. This is clearly an area that needs further exploration and quality improvement as we seek to provide high-quality postacute care for the older, frailer population.7

In addition to enhancing communication with our health system’s community-based teams, we focused on improving relationships with the four partner SNFs. It was hypothesized that extending the role of the conversation nurse into the SNF would decrease readmissions and increase referrals to hospice as a result of continued goals-of-care conversations. Given these preliminary positive results, the health system funded a full-time position dedicated to this role.

Like many other palliative care teams, the Care New England palliative care team is multidisciplinary and could have utilized a social worker, NP, physician, or nurse to see patients in the postacute facilities. We chose to use a conversation nurse because of the effective communication skills required for this role, their strong knowledge of the principles of hospice and palliative medicine, and the need for full symptom assessment, since so many of our patients had high symptom burdens.9 Nurses are well qualified to talk with patients about their goals for care and to complete the clinical assessments that are required to develop an appropriate care plan for effective symptom control and clinical management of patients with serious illness. In addition, communication is a core competency of nursing, and nurses have a responsibility in the care of the dying to educate patients and families about end-of-life issues and to encourage discussions about life preferences.10

Many of the patients (53%) seen by the conversation nurse eventually transitioned into hospice or home-based palliative care. Review of patients’ EMRs indicated that many of the patients seen by palliative care and transitioned to an SNF had met the clinical criteria for hospice but, for a variety of reasons, had not chosen hospice. A benefit of hospice care is the development of a clear care plan that allows for the management of symptoms in a patient’s residence without requiring an unwanted hospitalization. It was suspected that lower readmission rates for patients in hospice at the SNF was related to clear goals of care as well as a thorough care plan to meet the patients’ needs outside of the hospital.

The strengths of this project include the development of collaborative relationships with our community partners, which we felt was essential to the success of this pilot. The four partner facilities we worked with were very open to the addition of a palliative care nurse and were helpful during the integration process at their facilities. We observed that using a staff member with conversation skills and care transitions experience in the role of conversation nurse was an asset that contributed to the success of this initiative. Our collaboration with SNFs allowed the clinicians there to help us monitor patients, to identify those who were not responding well to various skilled services, and to help patients and family members understand the prognosis and the treatment options. A detailed review of patients’ cases and the development of coordinated processes with our home health agency seemed to improve the transition of patients into community palliative care services. Alignment with our regional quality improvement organization, Healthcentric Advisors, enhanced our community partnerships for this patient population and helped to stimulate conversation with our community partners about collaborative ideas to improve transitions of care.

Weaknesses of this project include the fact that it was a pilot project studying a small number of patients served by one community hospital. While this project was funded in part by a Practice Change Leader grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation and the Atlantic Philanthropies, the role of the conversation nurse did not receive separate funding, and we had to halt that part of the project early due to conflicting clinical responsibilities. (Starting in February 2017, the system’s home health agency hired a full-time nurse dedicated to developing and expanding this role.) Other limitations include the fact that while the four partner SNFs welcomed this form of intervention in their facilities, other facilities may not be as flexible. When patients at a facility come into hospice from skilled services, the facility receives a lower level of financial reimbursement, which may be a barrier to some facilities engaging in such a partnership.

Conclusion

A changing payment landscape might incentivize quality of care over quantity of care and may encourage health care providers to work together in novel ways.11 Financial benefits such as decreased readmission rates are the by-products of providing optimized medical and patient-centered care.12,13 While most inpatient acute care facilities now have palliative care programs, there is a need to bring that specialized care into the SNF and home-based services and a need for improved communication about what matters most to patients as they approach the end of their lives.14

References

1. Smith G, Bernacki R, Block SD. The role of palliative care in population management and accountable care organizations. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(6):486-494.

2. Meier DE. Focusing together on the needs of the sickest 5%, who drive half of all healthcare spending. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(10):1970-1972.

3. Pacala JT. Is palliative care the “new” geriatrics? Wrong question—we’re better together. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(10):1968-1970.

4. Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JPW, et al. Change in end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries: site of death, place of care, and health care transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. JAMA. 2013;309(5):470-477.

5. O’Connor NR, Moyer ME, Behta M, Casarett DJ. The impact of inpatient palliative care consultations on 30-day hospital readmissions. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(11):956-961.

6. Bharadwaj P, Helfen KM, Deleon LJ, et al. Making the case for palliative care at the system level: outcomes data. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(3):255-258.

7. Miller SC, Dahal R, Lima JC, et al. Palliative care consultations in nursing homes and end-of-life hospitalizations. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(6):878-883.

8. Rochon T, Barzilai K, Hall C, Teno JM. Meeting the needs of long term care: initial development and evaluation of a nurse practitioner palliative care consult service. Poster presented at: 21st National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Management and Leadership Conference; September 11-13, 2006; New York, NY.

9. Lally K, Rochon T, Roberts N, Adams KM. The “conversation nurse” model: an innovation to increase palliative care capacity. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2016;18(6):556-563.

10. American Nurses Association. Position statement: nurses’ roles and responsibilities in providing care and support at the end of life. https://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/EthicsStandards/Resources/Ethics-Position-Statements/EndofLife-PositionStatement.pdf. Effective 2016. Accessed January 2, 2018.

11. Patel K, Masi D. Palliative care in the era of health care reform. Clin Geriatr Med. 2015;31(2):265-270.

12. Kerr CW, Donohue KA, Tangeman JC, et al. Cost savings and enhanced hospice enrollment with a home-based palliative care program implemented as a hospice–private payer partnership. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(12):1328-1335.

13. Lustbader D, Mudra M, Romano C, et al. The impact of a home-based palliative care program in an accountable care organization. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(1):23-28.

14. JM Teno, BR Clarridge, V Casey, et al. Family Perspectives on End-of-Life Care at the last place of care. In: Meier DE, Isaacs SL, Hughes RG, eds. Palliative Care: Transforming the Care of Serious Illness. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010;235-250.