Promoting Access to Quality Palliative Care in Care Facilities

ECRI Institute and Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging (ALTC) have joined in collaboration to bring ALTC readers periodic articles on topics in risk management, quality assurance and performance improvement (QAPI), and safety for persons served throughout the aging services continuum. ECRI Institute is an independent nonprofit that researches the best approaches to improving health care.

Although many long-term residents in nursing facilities suffer from multiple chronic, debilitating conditions, including dementia, less than half of nursing homes (NHs) in the United States have a framework or protocol for offering comprehensive palliative care.1-3 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) defines palliative care as “patient and family-centered care that optimizes quality of life by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering. Palliative care throughout the continuum of illness involves addressing physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual needs and to facilitate patient autonomy, access to information, and choice.”4

Ideally, palliative care is initiated at the request of an individual’s treating physician soon after receiving a diagnosis of a life-threatening or chronic debilitating illness.5 Oftentimes, however, NH residents are not offered palliative care until they have been diagnosed with terminal illness with a life expectancy of less than 6 months, making them eligible for the Medicare/Medicaid hospice benefit. This happens despite studies indicating that quality of care and survival is better for NH residents who receive palliative care.6,7

Palliative care is typically provided through a team approach that includes comprehensive, coordinated pain and symptom control, care of psychological and spiritual needs, family support, and assistance in making transitions throughout the continuum of care. Teams include professionals from medicine, nursing, and social work, with support from chaplaincy, nutrition, rehabilitation, and pharmacy, and in collaboration with other health care providers as needed.

As NH residents often transition between care settings, the need for comprehensive palliative care across the continuum of care is pressing. Transitions between care settings can be severely disruptive and disorienting, and fraught with risk for adverse events. Even when a NH provides comprehensive palliative care, its care plan for the resident can be frustrated by discontinuity when a resident is transferred to a hospital that lacks a palliative care program or when the hospital’s palliative care team is not involved in the resident’s inpatient care. In order to close this gap, some nursing facilities partner with palliative care teams moving between hospitals and nursing facilities.8

In an effort to optimize their care, some nursing facilities are joining learning collaboratives designed to help them develop and improve palliative care infrastructures. For example, the Nursing Home Palliative Care Collaborative of Rhode Island, funded by CMS, provides education, best practices, and interfacility discussion, focusing efforts on the following domains of care: identifying proxy decision makers and engaging in advance care planning; talking with residents about their prognosis; conducting care conferences that discuss goals for care; implementing procedures for pain assessment; and assessing the need for and access to spiritual care.9

In the 2014 report, Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life, the Institute of Medicine identified 12 core components of comprehensive, quality end-of-life care and concluded that the provision of palliative care remains the greatest challenge.10 Although no formal quality reporting program exists for palliative care, most health care settings where palliative care is provided participate in federal quality initiatives.

Facilitating Access to Palliative Care

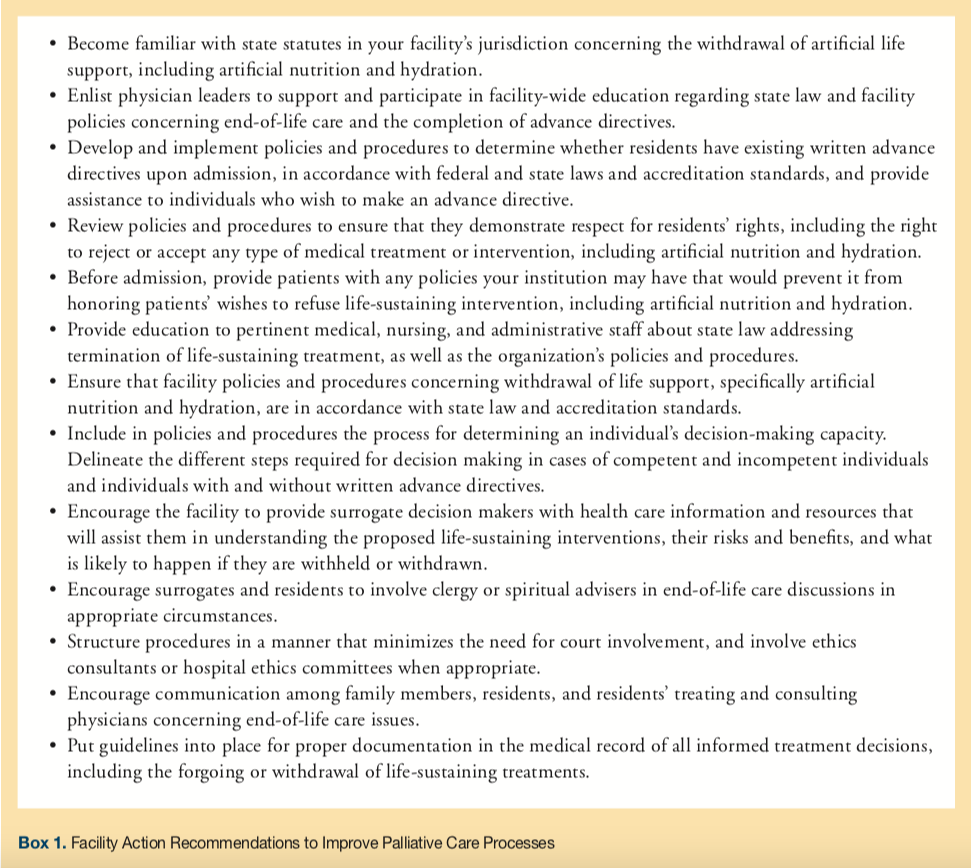

A breakdown of practical steps facilities can take to promote access to palliative care is found in Box 1. Information about palliative care should be offered as often as necessary to ensure that the resident has the information they need at each stage of illness to appropriately ameliorate any distressing symptoms and improve the quality of life. As the resident’s condition changes, the resident and their family or surrogate decision maker may need to reevaluate the treatment or care plan, facilitating timely access to palliative care consultation and services consistent with the resident’s needs, preferences, and goals of care. Providers should also ensure that policies and procedures are in place regarding preparation of advance directives (if desired) by deciding upon advance directives and identifying the resident’s legally authorized health care decision maker. In the event the resident lacks decision-making capacity, care professionals should provide the resident’s authorized decision maker with information and counseling about palliative care. Facilities in states that have enacted patient “right to know” laws requiring providers to provide information about end-of-life and palliative care to individuals and facilitate access to it should ensure that written facility policy incorporates all such legal and regulatory requirements as may be appropriate.

As geographic location may determine access to palliative care services, nursing facilities considering making an arrangement with a hospital palliative care program should be aware that palliative care is more limited in hospitals in southern states and in smaller rural hospitals. Facilities in geographic areas that generally lack access to trained and credentialed palliative care providers might consider the use of telemedicine to facilitate access to palliative care consultation. A study of palliative care consultations provided by telemedicine for small rural hospitals in northeastern states found that limiting factors were ensuring adequate technical assistance at the hospitals and adequate coverage for conducting the conferences.11 Nursing facilities considering implementing a telemedicine program for palliative care can find information and technical assistance for organizing a telemedicine palliative care initiative from the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC).12

Individuals who are members of racial or ethnic minorities may lack equal access to palliative care for numerous reasons and may reject palliative care because of unfamiliarity or misconceptions about it.13,14 A high percentage of African American respondents (71%) to a national survey about palliative care reported their concerns that palliative care could interfere with doing “whatever it takes” to extend a patient’s life.15 To ensure that all populations have equal access to palliative care, risk managers may wish to track the use of palliative care services among ethnic and racial minority residents in their facilities. The availability of palliative care services should be discussed in admission brochures, on facility websites, and in foreign languages appropriate for the resident population.

Article continues on page 2

Surrogate Decision Making

It is clearly established in the United States that patients who are legally competent and who have the mental capacity to make decisions about their health care have the right to refuse treatment even when such refusal is likely to result in death. Physician’s clinical judgments are usually considered sufficient for determining whether patients have the capacity to make informed health care decisions. Patients who have been adjudicated as mentally incompetent or who lack the capacity to make health care decisions must have their rights exercised by a family member or an appointed surrogate. The Patient Self-Determination Act provides competent individuals the right to designate a surrogate to make health care and treatment decisions for them in the event that they lose the capacity to make such decisions for themselves. For individuals who do not designate a surrogate, many states provide for the appointment of a next-of-kin surrogate. Surrogate decision makers are typically instructed to use the “substituted judgment” standard—that is, to make the treatment decisions that the individual would have made if she or he had the capacity to decide. States also establish the legal standard of proof required to show what the resident’s wishes would have been.

Surrogate decision makers experience significant moral, emotional, and cognitive demands in carrying out their responsibilities. There is also concern that surrogates frequently make inaccurate decisions that do not reflect what the incapacitated individual would have wanted. Researchers have examined this issue by analyzing studies that used hypothetical scenarios to assess surrogate accuracy and the degree to which patients and their surrogates agreed. Patients were asked whether, under specific scenarios, they would want to receive specified medical interventions. The patients’ surrogates were then independently asked to predict what choices the patients would make in the same hypothetical scenarios, 90% of which involved life-sustaining interventions. The analysis16 of more than 19,500 patient-surrogate paired responses concluded that surrogates predicted patients’ treatment preferences with 68% accuracy. Patient-designated surrogates predicted patients’ treatment preferences with 69% accuracy, whereas legally assigned surrogates predicted patients’ treatment preferences with 68% accuracy. Patient-designated and next-of-kin surrogates incorrectly predicted patients’ end-of-life treatment preferences in one-third of cases. Despite their shortcomings, surrogates were found to be more accurate than physicians at predicting patients’ treatment preferences. The report’s authors concluded that reliance on surrogates may be defended as the best available method for implementing the substituted judgment standard.

Another study17 that involved structured interviews with 246 surrogate decision makers found that many would have preferred greater physician participation in decisions about feeding tube placement, and many reported that their information needs were not completely met. Eighty percent of surrogates reported discussing the benefits of feeding tube placement, whereas only 72% of surrogates reported discussing the risks of feeding tube placement with treating physicians. Approximately 66% of surrogates reported discussing what life would be like with and without the feeding tube. Additionally, approximately 41% reported wanting more information about these issues. The study’s author comments that physicians may be justified in taking a more active role in feeding tube decisions with surrogates and that many surrogates desire more information than may be required by general standards of informed decision making.

Based on the above findings and others, surrogates need more information from physicians. They should be informed about the nature of the dying process and what changes they can expect as the patient proceeds toward death and, ultimately, dies. In addition, surrogates should be reminded that physicians cannot accurately predict when patients will die.18 When communicating with surrogates and family members of patients who are on ventilators, physicians should also discuss how the ventilator will be withdrawn18 and respond to any questions concerning how death is clinically determined.

Risk managers should encourage their facilities to provide support to surrogate decision makers by ensuring that they are given timely and appropriate access to health care information and education resources that may assist them in understanding the risks and benefits of proposed treatments and in communicating their concerns to treating physicians.

Measuring and Improving Quality

The provision of palliative care entails familiar and unique quality, patient safety, regulatory, and litigation risks. Expert advisors on performance measure coordination for quality palliative care suggest an approach that emphasizes clinically focused quality measures but also expands to include measures that follow the patient and the patient’s full set of experiences.20

Each organization must decide its priorities for performance improvement, aligning them with its strategic goals, and then select measures to monitor those areas. The organization’s priorities are outlined in its quality and patient safety plan, which provides the organization with a roadmap for its quality and safety initiatives.

For many organizations, including performance benchmarks used by regulators and accreditors in their quality and patient safety plans is essential to ensure compliance with the Medicare program and access to federal funds. The findings from previous accreditation surveys and state inspections may also drive priorities and measure selection, particularly if an area was previously found deficient.

Additionally, the risk management and quality improvement departments may select certain measures to monitor the effectiveness of projects to improve patient safety and quality. The projects may address areas of risk to the organization based on information from multiple sources, including event reports and investigations, feedback from staff and patients, financial and operational documents, internal and external reports, and direct observation.

Seven care practices have been identified as potential process measures for tracking palliative care improvement in nursing facilities (Box 2).19 Each practice should be completed and documented within 14 days of admission or within 14 days of change in diagnosis/prognosis indicating a significant decline in overall health except for pain assessment, for which a different time frame is indicated. To obtain baseline data, facility teams would conduct random chart reviews, focusing on documentation at admission or most recent change in diagnosis/prognosis. Facilities may need to work incrementally to achieve a 100% completion rate for each of the 7 practices. Elements of varying preferred practices associated with each of seven practices and their rationale are discussed in greater detail in the Nursing Home Palliative Care Toolkit.19

In 2012, the National Quality Forum endorsed 14 quality measures for palliative and end-of-life care. Stated generally, the measures include pain screening and assessment; dyspnea screening and treatment; documentation of patient care preferences, including documentation of discussion of the patient’s spiritual and religious concerns or documentation that the patient/caregiver does not want to discuss such matters; percentage of patients who die expectantly in the hospital without deactivation of an implanted cardioverter defibrillator; family evaluation of end-of life care; and bereavement care.20

CAPC provides performance measures for measuring the quality and impact of palliative care programs and identifies 4 categories of measurement: operational data (eg, volume and type of referrals, date of admission/consultation); clinical data (eg, pain and symptom control); customer data (eg, patient, family, and health care provider satisfaction surveys); and financial data (eg, billing revenues, cost per day, length of stay).21

Although developed for hospitals, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) quality measures to evaluate palliative care teams in VA hospitals may also be useful for nursing facilities, as the measures assess the incidence of discussion about goals, chaplain visits, and advance directives. 22,23

Conclusion

Establishing a facility-based palliative care program is a complex task that requires careful consideration of a variety of factors that are unique to each facility. Leaders in facilities considering implementing facility-based palliative care programs should be aware of resources that can help determine if their facilities have the capacity to provide palliative care, as well as tools and resources to guide the development and implementation of a palliative care program. The palliative care program should be designed to reflect the facility’s unique mission, needs, and resident population, in light of facility constraints.

Once palliative care programs are established, NHs can use the strategies described here to promote access, ensure appropriate involvement of surrogate decision-makers, and monitor quality based on established measures.

References

1. Lester PE, Stefanacci RG, Feuerman M. Prevalence and description of palliative care in US nursing homes: a description study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33(2):171-177.

2. Javier NS. Palliative care for the nursing home resident with dementia. Med Health R.I. 2010;93(12):379-81.

3. Meier D, Lim B, Carlson MD, Raising the standard: palliative care in nursing homes. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(1):136-40.

4. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). F tag 309—quality of care-advance copy [memorandum to state survey agency directors online]. Ref S&C 12-48-NH. 2012 Sep 27 [cited 2014 Nov 5]. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/Downloads/Survey-and-Cert-Letter-12-48.pdf

5. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (NCP). Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. 3rd ed. https://www.nationalconsensusproject.org/guidelines_download2.aspx. Published March 2013. Accessed January 22, 2018.

6. Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Eng J Med 2009;361(16):1529-1538.

7. Kurella TM, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, et al. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 2009;361(16):1539-1547.

8. Corcoran A, Lim B, Hanson L. Hospice and non-hospice models of palliative care delivery in long-term care. Presented at: Long-Term Care SIG Symposium AAHPM-HPNA Annual Assembly; March 4, 2010; Boston, MA.

9. Miller SC. Nursing home/hospice partnerships: a model for collaborative success—through collaborative solutions. https://www.nhpco.orghttps://s3.amazonaws.com/HMP/hmp_ln/imported/public/nhhp-final-report.pdf. Published February 2007. Accessed January 22, 2018.

10. Institute of Medicine (IOM). Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. https://www.iom.edu/Reports/2014/Dying-In-America-Improving-Quality-and-Honoring-Individual-Preferences-Near-the-End-of-Life.aspx. Published September 17, 2014. Accessed January 22, 2018.

11. Menon PR, Ramsay A, Stapleton RD. Telemedicine as a medical intensive care unit/palliative care tool to improve rural health care [abstract online]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2011.183.1_MeetingAbstracts.A1670. Accessed January 22, 2018.

12. Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC): Organizing a telemedicine palliative care initiative: a technical assistance monograph from the IPAL-OP project [online]. Published 2012. Accessed January 22, 2018.

13. Hauser J, Sileo M, Araneta N, et al. Navigation and palliative care. Cancer. 2011;117(suppl 15):3585-3591.

14. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742.

15. Regence Foundation. Americans choose quality over quantity at the end of life, crave deeper public discussion of care options. https://www.cambiahealthfoundation.org/media/release/07062011njeol.html. Published March 8, 2011. Accessed January 22, 2018.

16. Shalowitz DI, Garrett-Mayer EM, Wendler D. The accuracy of surrogate decision makers: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(5):493-497.

17. Lewis CL, Hanson LC, Golin C, et al. Surrogates’ perceptions about feeding tube placement decisions. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61(2):246-252.

18. Luce JM, Alpers A. End-of-life care: what do the American courts say? Crit Care Med. 2001;(suppl 2):N40-N45.

19. Healthcentric Advisors. Nursing home palliative care toolkit. https://healthcentricadvisors.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/NH-Palliative-Care-Toolkit_2014.pdf. Published June 2014. Accessed January 22, 2018.

20. National Quality Forum (NQF). Palliative care and end-of-life care—a consensus report. https://www.qualityforum.org/Projects/Palliative_Care_and_End-of-Life_Care.aspx. Published April 2012. Accessed January 22, 2018.

21. Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC): Metrics and measurement in palliative care. https://www.capc.org/topics/metrics-and-measurement-palliative-care. Accessed January 22, 2018.

22. Lu H, Trancik E, Bailey FA, et al. Families’ perceptions of end-of-life care in Veterans Affairs versus non-Veterans Affairs facilities. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(8):991-996.

23. Casarett D, Pickard A, Baily FA, et al. A nationwide VA palliative care quality measure: the family asses