Prevention of Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis in Nursing Home Residents

Incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD) is an inflammatory skin condition that occurs when the skin is exposed to urine or stool.1 IAD is also known as perineal dermatitis or diaper rash, but incontinence-associated dermatitis is the preferred term because it more precisely identifies the cause of the dermatitis, acknowledges that the condition may affect more than the perineum, and because diaper rash is considered to be a demeaning term when used for adults.2,3 More recently, the term moisture–maceration injury has been used. This broader new term is the most useful, as it acknowledges that skin injury can occur not only from the skin’s exposure to urine or stool, but also from perspiration, wound exudates, or other body fluids.4

Although incontinence has been considered a normal part of aging, it can be attributed to factors beyond aging, including changes in medications or hormone levels, infections, or dementia; thus, IAD should not be dismissed as merely a consequence of a condition associated with aging. It is imperative to identify the etiology of IAD, especially when new-onset incontinence occurs, because incontinence can be transient, manageable, or reversible.5 Prevention of IAD is crucial, as it is a major risk factor for pressure ulcers, which can easily become infected and lead to loss of life. Furthermore, caring for a patient with skin breakdown or pressure ulcers is time-consuming and increases the cost of providing care.3

As the population of elders in the United States increases, IAD is becoming a growing concern, especially because it is also a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) quality-of-care indicator. This review aims to identify the evidence-based practices that might be used to prevent IAD in nursing home residents.

Methods

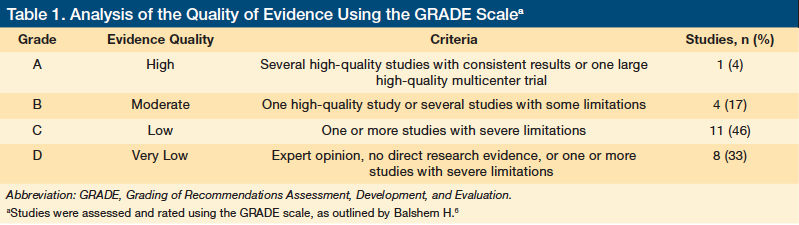

This literature review included searches of the University of Cincinnati Search Summons, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), and PubMed/MEDLINE databases using the following key words: incontinence-associated dermatitis, perineal dermatitis, and moisture–maceration injury. The search yielded more than 1100 results. Inclusion criteria were journal articles with full text online and those related to the prevention of IAD in nursing home residents. Excluded studies were those conducted in facilities other than nursing homes and those evaluating the consequences of IAD rather than prevention strategies. Articles were analyzed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for rating the quality of evidence.6 According to this approach, articles were graded from A to D, with A being of the highest quality and D being of the lowest quality.

Results

Twenty-four articles met the inclusion criteria. Almost half were expert opinions or systematic reviews. Many of the articles discussing trials or program interventions had conflict-of-interest limitations. Table 1 depicts the number of articles and their GRADE ratings.6

Rates and Risk Factors

The literature review showed that, although urine or fecal incontinence may be common in nursing home residents, the documented rate of IAD varies considerably. Junkin and

Selekof7 found bowel and bladder incontinence rates as high as 78% in nursing home residents, with about 43% having some form of IAD. In contrast, a study by Bliss and colleagues8 that reviewed the records of 10,215 residents found IAD in only 5.7%, with 48% of those having both urine and fecal incontinence.

Risk factors for IAD were consistent throughout the literature and included advanced age, chemical irritation, infection, length of exposure to moisture, and mechanical stresses. As people age, their skin becomes more susceptible to IAD because of a thinning epidermis and dermis, reduced blood supply, and increased moisture loss.9,10 In addition, cell turnover slows, which means healing takes longer once IAD develops. Gray9 identified chemical irritation (from urine or stool), pathogen overgrowth or infection (such as yeast or Staphylococcus), and mechanical damage (such as friction and shear) as contributing factors to IAD development. The normal protective acid mantle on the skin is lost when exposed to the alkalinity of feces or urine.11 Ammonia in urine is caustic, making the skin susceptible to breakdown, and fecal contact with broken skin can cause infection and deeper skin damage. In one study, Gray and associates4 found that the duration of urine and fecal exposure to the skin was the major contributing factor to IAD. In another study, Gray12 identified poor nutrition and decreased mobility as risk factors. Langemo and colleagues13 found that being a woman or cognitively impaired also conferred risk.

Once IAD occurs, there is a high risk for pressure ulcer development. Junkin and Selekof7 reported a 37.5% greater risk of developing pressure ulcers as well as an increased risk of infection and morbidity among patients with incontinence. Nix and colleagues14 also identified IAD as a major risk factor for developing pressure ulcers. The Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Ulcer Risk, a validated assessment tool, includes moisture from urine and fecal incontinence as risk factors for pressure ulcers.2

Core Prevention Measures

Minimizing exposure time to urine and feces and implementing a structured skin care regimen are core IAD prevention measures found repeatedly throughout the literature.15 Beeckman and colleagues16 recommended using a pH-balanced skin cleanser, skin moisturizer, and moisture-repellent skin barrier for all residents at risk of IAD, noting that perineal skin cleansers or no-rinse foams are preferable to cleansing with traditional washcloths, soap, and water. Gray12 echoed these recommendations, adding that the cleansing product should not compromise the skin’s moisture barrier. Voegeli17 found that soap and water are most commonly recommended for general skin cleansing, but warned that they can be damaging to a patient with or at risk for IAD. Hodgkinson and colleagues15 performed a systematic review of the literature, and their conclusions support a structured skin care regimen using a no-rinse cleanser. They also concluded that some types of disposable briefs might prevent worsening of skin irritation.

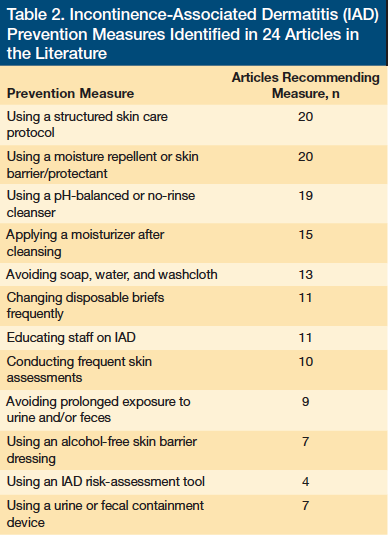

Hunter and colleagues18 performed a quasi-experimental study to assess the effectiveness of skin care protocols on skin breakdown in two nursing homes. The study involved a 3-month preintervention assessment of skin breakdown, followed by a staff education program on using new skin care products (a no-rinse body wash and skin protectant), and then another 3-month assessment of skin breakdown after use of these products. Although both nursing homes reported a reduction in skin breakdown upon using the new skin care regimen, neither noted a significant enough reduction to reach statistical significance. This study included pressure ulcers, perineal dermatitis, cracks and fissures, skin tears, and blisters in the skin breakdown descriptions. When examining perineal dermatitis alone, there was a reduction in this condition from 15 residents before the intervention to eight residents afterward. Clinical guidelines issued by the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) and the Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurses Society suggest that a skin care program that includes cleansing and protecting the skin from incontinence is best for preventing pressure ulcers.19,20 Table 2 lists the prevention measures identified in this review and the number of articles recommending each intervention.

Patient Comfort, Quality of Care and Costs

Prevention of IAD has many practice implications for improving patient comfort and quality of care while reducing pressure ulcer development and costs. Facility-acquired pressure ulcers are considered to be a main quality indicator by regulatory agencies, such as CMS and The Joint Commission (formerly the Joint Commission Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations).3 IAD is usually a partial thickness injury that exposes the nerves in the dermis, causing burn-like pain. Frequent cleansing of the skin after incontinent episodes may also cause pain and can result in further injury if not performed carefully. Pain has been shown to increase morbidity and length of stay in the long-term care and acute care settings.13 Skin care protocols to prevent IAD may also reduce costs. Bliss and colleagues21 performed a multisite quasiexperimental study of four different skin care protocols in 981 nursing home residents to determine the cost and efficacy of these protocols. There was no significant difference in the protocols or the number of cases of IAD that developed. Cost savings were found with the use of an alcohol-free barrier film applied three times weekly. Guest and associates22 reviewed the literature on using a transparent barrier film dressing in IAD and found that it was more cost-effective than traditional daily applications of topical creams and ointments. In 2011, Palese and Carniel23 reported on the effects of an incontinence care program that included 63 nursing home residents. This program implemented the use of new products, educated staff on the proper use of these

products, and provided staff with access to a certified continence nurse. The authors acknowledged the limitation that the study’s sponsor had supplied the products. They reported that the program resulted in a decrease in risk factors for IAD and in direct costs. These findings reinforce the importance of providing staff education on preventing IAD.

Determining the etiology of skin breakdown by distinguishing between lesions caused by moisture, incontinence, pressure, shear, or friction aids in choosing the appropriate treatment and improves the quality of care and outcomes. Further, incorrectly diagnosing the cause of patients’ skin injuries can affect reimbursement, research, and mandatory reporting to regulatory agencies; thus, it is key to educate

staff about risk factors, prevention measures, use and cost of products, risk-assessment tools, and how to differentiate between types of skin injury.13 Recent risk-assessment tools, such as the Perineal Assessment Tool (PAT), have been developed to help prevent IAD by identifying residents at risk and beginning early intervention.14

Gap Analysis

A limited number of quality clinical studies have explored the prevention of IAD in nursing home residents. Almost half of the articles in this literature review were systematic reviews of the literature or reviews of expert opinions rather than clinical research. Some experts have written several articles over the years and continue to investigate IAD; 33% of the articles reviewed were written within the past 3 years, which attests to the importance and timeliness of this topic. However, the lack of high-quality studies makes it difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of the reported prevention protocols.

In general, there is a consensus in the literature that a skin care protocol is important for preventing IAD, but the wide range of products used in the reported studies and the use of the broad term skin protectant make it difficult to compare evidence-based outcomes. It would be beneficial if several studies had compared specific skin protectants (eg, zinc oxide with petrolatum) or different types of disposable briefs for reducing IAD.

The gap in the variance of the prevalence of IAD reported ranged from 5.7% to more than 50%. Some studies included residents with either urinary or fecal incontinence and some included residents with both. In addition, methods used to identify IAD were inconsistent, leading to varied prevalence rates. The use of validated risk-assessment tools would be helpful in establishing an accurate prevalence rate.

Finally, as mentioned previously, various terms are used in the literature to describe IAD, including perineal dermatitis and the newer term moisture–maceration injury. Consistent terminology would make it easier to research the topic and improve the education of healthcare providers, as clear definitions are important for identifying the type of skin injury and implementing the correct interventions.

Future Research Suggestions

Clinical studies of IAD prevention, rather than only systematic reviews, are needed. These should include the evaluation of prevention protocols, staff education, and types of products used. Comparing traditional soap, water, and washcloth cleansing with one-step products would also be useful. For example, a study by Al-Samarrai and colleagues24 found that using a one-step incontinence cleansing system resulted in greater cleansing frequency and decreased the time spent on incontinence care. Several products have been shown to decrease cost, but they have not been thoroughly evaluated for efficacy or for their ability to decrease the prevalence of IAD.

Evaluations of various types of adult briefs and comparing briefs with underpads are other areas of research that would be useful for making practice decisions. Beguin and colleagues25 designed an adult brief that creates an acidic pH on the surface and airflow at the side panels to avoid maceration of the skin and decrease the occurrence of IAD. The authors evaluated the efficacy of these optimized briefs in 12 patients with preexisting IAD. Of these patients, eight had healed within 21 days of being switched to the optimized briefs. Fader and associates26 studied the effect on the skin of less frequent changes of adult briefs. The authors reported that although superabsorbent briefs are designed to keep residents drier, they can increase skin wetness if left on for an extended period. Although the findings did not reach statistical significance, the authors found that five of 81 individuals developed a stage II pressure ulcer during the less frequent pad-changing regimen. This finding warrants further research.

Use of validated measurement tools to evaluate the patient for IAD versus subjective data of the researcher is another area for improvement in clinical study design. Zimmaro Bliss and colleagues27 studied a large group of nursing home residents with IAD and educated the staff before the residents’ IAD was assessed, but they used subjective findings to characterize IAD severity, such as broken skin, small or large blisters, intense redness, or rash.

Gray and associates1 identified three instruments created specifically to evaluate IAD: (1) the PAT; (2) the Skin Condition Assessment Tool; and (3) the Perineal Dermatitis Grading Scale, but these tools are rarely used, likely because of a lack of awareness of their existence. The PAT evaluates IAD risk by irritant (stool or urine), exposure time, skin condition, and contributing factors.1 The Skin Condition Assessment Tool focuses more on how red and eroded the skin is, whereas the Perineal Dermatitis Grading Scale evaluates the severity of the skin injury and measures changes following specific nursing interventions.1 Most facilities use the NPUAP Staging System to define the IAD injury; however, this system was designed for staging pressure-related injuries and should not be used to evaluate IAD. Further research is needed comparing all of the available skin assessment tools in clinical practice, so that more objective data on their efficacy is provided.

Conclusion

The problem of IAD in nursing home residents is widely acknowledged. A review of the literature supports a structured skin care protocol for IAD prevention that includes gentle cleansing, moisturizing, and use of skin protectants. A number of systematic reviews were found, but few studies examined the economical outcomes of specific products or compared their efficacy in a head-to-head manner. More high-quality studies are needed to measure the clinical efficacy of all suggested prevention measures. In addition, staff education on IAD risk factors, prevention measures, and terminology, and on differentiating between types of IAD and pressure ulcers are important for improving patient care and clinical outcomes. The increased risk of pressure ulcers in residents with incontinence is well reported. Preventing IAD will help decrease pressure ulcer incidence, patient discomfort, morbidity, and the cost of care for this common disorder, while also improving patients’ quality of life.

References

1. Gray M, Bliss DZ, Doughty DB, et al. Incontinence-associated dermatitis: a consensus. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2007;34(1):45-54.

2. Gray M. Incontinence-related skin damage: essential knowledge. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2007;53(12):28-32.

3. Nix D, Haugen V. Prevention and management of incontinence-associated dermatitis. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(6):491-496.

4. Gray M, Black J, Baharestani MM, et al. Moisture-associated skin damage: overview and pathophysiology. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2011;38(3):233-241.

5. Farage MA, Miller KW, Berardesca E, Maibach HI. Incontinence in the aged: contact dermatitis and other cutaneous consequences. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57(4):211-217.

6. Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401-406.

7. Junkin J, Selekof JL. Beyond “diaper rash”: incontinence-associated dermatitis: does it have you seeing red? Nursing. 2008;38(suppl 11):56nh1-56nh10.

8. Bliss DZ, Savik K, Harms S, Fan Q, Wyman JF. Prevalence and correlates of perineal dermatitis in nursing home residents. Nurs Res. 2006;55(4):243-251.

9. Gray M. Preventing and managing perineal dermatitis: a shared goal for wound and continence care. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2004;31(suppl 1):S2-S10.

10. Nazarko L. Managing a common dermatological problem: incontinence dermatitis. Br J Community Nurs. 2007;12(8):358-363.

11. Holloway S, Jones V. The importance of skin care and assessment. Br J Nurs. 2005;14(22):1172-1176.

12. Gray M. Optimal management of incontinence-associated dermatitis in the elderly. Am J Clin Derm. 2010;11(3):201.

13. Langemo D, Hanson D, Hunter S, Thompson P, Oh IE. Incontinence and incontinence-associated dermatitis. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2011;24(3):126-140.

14. Nix D, Ermer-Seltun J. A review of perineal skin care protocols and skin barrier product use. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004;50(12):59-67.

15. Hodgkinson B, Nay R, Wilson J. A systematic review of topical skin care in aged care facilities. J Clin Nurs. 2006;16(1):129.

16. Beeckman D, Schoonhoven L, Verhaeghe S, Heyneman A, Defloor T. Prevention and treatment of incontinence-associated dermatitis: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(6):1141-1154.

17. Voegeli D. Care or harm: exploring essential components in skin care regimens. Br J Nurs. 2010;19(13):810-819.

18. Hunter S, Anderson J, Hanson D, Thompson P, Langemo D, Klug MG. Clinical trial of a prevention and treatment protocol for skin breakdown in two nursing homes [published correction appears in J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2003;30(6):350]. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2003;30(5):250-258.

19. Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurses Society. Guidelines for prevention and management of pressure ulcers. WOCN Clinical Practice Guideline Series. Glenview, IL: WOCN Society; 2003:14.

20. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Pressure Ulcer Prevention Quick Reference Guide. https://npuap.org/Final_Quick_Prevention_for_web_2010.pdf. Accessed April 24, 2012.

21. Bliss DZ, Zehrer C, Savik K, Smith G, Hedblom E. An economic evaluation of four skin damage prevention regimens in nursing home residents with incontinence: economics of skin damage prevention. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2007;34(2):143-152.

22. Guest J, Greener M, Vowden K, Vowden P. Clinical and economic evidence supporting a transparent barrier film dressing in incontinence-associated dermatitis and peri-wound skin protection. J Wound Care. 2011;20(2):76.

23. Palese A, Carniel G. The effects of a multi-intervention incontinence care program on clinical, economic, and environmental outcomes. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2011;38(2):177-183.

24. Al-Samarrai NR, Uman GC, Al-Samarrai T, Alessi CA. Introducing a new incontinence management system for nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8(4):253-261.

25. Beguin A, Malaquin-Pavan E, Guihaire C, et al. Improving diaper design to address incontinence associated dermatitis. BMC Geriatrics. 2010;10:86.

26. Fader M, Clarke-O’Neill S, Cook D, et al. Management of nighttime urinary incontinence in residential settings for older people: an investigation into the effects of different pad changing regimes on skin health. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12(3):374-386.

27. Zimmaro Bliss D, Zehrer C, Savik K, Thayer D, Smith G. Incontinence-associated skin damage in nursing home residents: a secondary analysis of a prospective, multicenter study. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2006;52(12):46-55.