Preventing Multidrug-Resistant Organisms and Controlling High-Profile Infectious Disease Outbreaks in LTC

ECRI Institute and Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging (ALTC) have joined in collaboration to bring ALTC readers periodic articles on topics in risk management, quality assurance and performance improvement (QAPI), and safety for persons served throughout the aging services continuum. ECRI Institute is an independent nonprofit that researches the best approaches to improving health care.

Long-term care (LTC) facilities pose unique infection control risks to residents, as these facilities are comprised of shared living spaces, circulated air, high-touch surfaces, and equipment (eg, physical and occupational therapy equipment), and residents generally socialize freely with one another. They may have direct or indirect contact with visitors and staff as well. Residents may introduce infections into the facility when they are transferred from other care settings or home.1 Infections that commonly occur in LTC facilities2 can be found at Box 1.

Infections in LTC residents are associated with morbidity and mortality, hospital admissions and emergency department visits, antimicrobial use, and related costs. A 2000 review estimated that 25% to 50% of hospital admissions of LTC residents—or about 153,000 to 306,000 US hospital admissions annually—are due to infection. It also found that in LTC rates of death associated with infection range from 0.04 to 0.71 per 1000 resident-days. Thus, the researchers projected, 21,880 to 388,370 resident deaths associated with infection occur each year, with pneumonia being the leading cause of death.3 Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the incidence of common endemic infections per 1000 resident-days. However, as one expert notes, it is not always clear whether death is attributable to the infection or to underlying chronic disease.4

Despite the susceptibility of LTC residents to infection and the relatively high frequency of infections in these settings, improvements in infection prevention and control can make a difference.

Antimicrobial Use and Antibiotic Resistance

Multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) are a pressing concern in LTC. An estimated 12.7 antibiotic-resistant infections per 1000 long-term skilled nursing facility residents occur annually.5 Inappropriate antimicrobial use not only promotes the emergence of MDROs, it also raises the risk of Clostridium difficile infection, medication side effects, and adverse drug reactions.

In April 2014, the World Health Organization issued a report that found that in many parts of the world, drug resistance has reached “alarming” levels and that a “major gap in knowledge” exists regarding the current threat level of antibiotic resistance in common bacteria. The report stated that, “A post-antibiotic era—in which common infections and minor injuries can kill—far from being an apocalyptic fantasy, is instead a very real possibility for the 21st century.”6 The following year, the White House announced a 5-year plan to combat antibiotic resistance. Developed in response to an executive order, National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria lists strengthening antibiotic stewardship programs in inpatient, outpatient, and LTC settings as a sub-objective.7

Indeed, studies show there is a need for improvement in antimicrobial use in LTC. In a literature review, the percentage of antibiotic orders in LTC facilities that were deemed appropriate ranged from only 49% to 62%.8 Another study found that even in residents with advanced dementia, most of whom had comfort as the primary goal of care, clinical criteria for antimicrobial initiation were present for only 44% of infections treated with antimicrobials. In addition, 48% of residents who were not colonized with an MDRO at baseline became colonized with an MDRO within a year.9

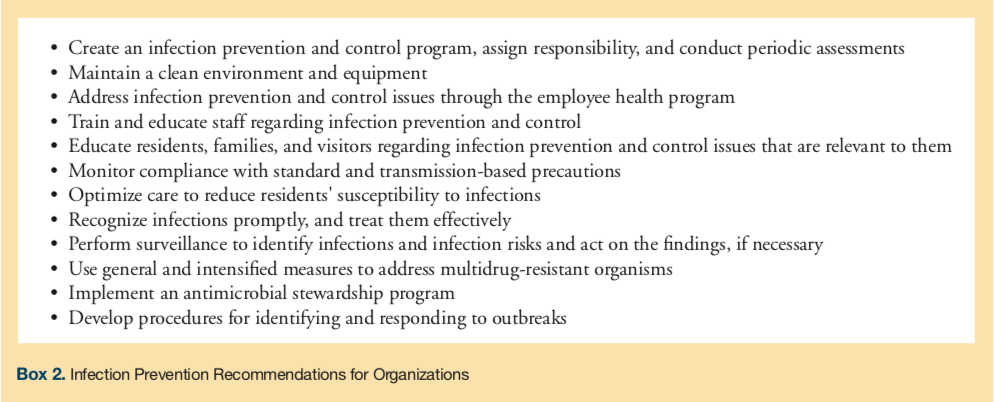

Coordination with other health care organizations is important when trying to optimize infection prevention strategies. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has called on health care organizations to work more closely together to stop the spread of antibiotic-resistant organisms. A 2015 report from the agency concluded that coordinated approaches to halt the spread of resistant organisms—for example, by implementing systems to alert receiving facilities when enhanced infection control is needed for transferred patients who are colonized or infected with resistant organisms—would have more impact than only programs based in individual facilities. Such approaches could avert an estimated 619,000 antibiotic-resistant, healthcare-associated infections over 5 years, the agency estimates.10 Box 2 provides recommended actions facilities can take to prevent infections.

Controlling Outbreaks

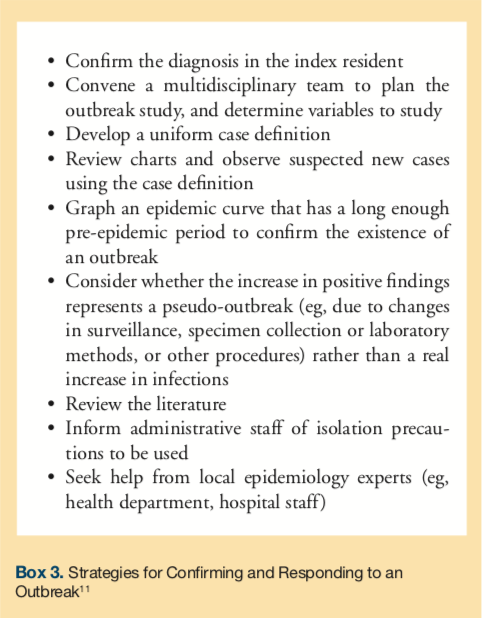

Despite facilities’ best efforts at prevention, infectious disease outbreaks will still occur due to the nature of LTC settings, as mentioned previously. Outbreaks are common in LTC, but, according to the Infectious Diseases Society of America, routine review of surveillance data can help organizations promptly recognize potential outbreaks. After an outbreak has already occurred, research suggests that facilities take the initial steps provided in Box 3 to confirm and plan a response to an outbreak in their settings.11 According to an email from Christopher J Crnich, MD, MS, (April 20, 2012), the organization may also consider training frontline staff to institute isolation precautions based on observed signs and symptoms, if indicated, until a diagnosis is established.

In addition, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiologists of America/Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology guideline “Infection Prevention and Control in the Long-Term Care Facility” recommends delineating authority for intervening during an outbreak. It suggests establishing a protocol for response that addresses authority for tasks such as relocating residents, restricting residents to their rooms, restricting visitors, obtaining cultures, instituting isolation, and administering treatment or prophylaxis. It also recommends obtaining consent for diagnostic and therapeutic outbreak measures on resident admission.2 Organizations should also address infection prevention and control in their emergency plans.

This article is excerpted from “Overview of Infection Prevention and Control,” part of ECRI Institute’s Continuing Care Risk Management (CCRM) program. To see more samples of guidance and recommendations available from CCRM, go to https://www.ecri.org/ccrm.

To read more articles in this issue, visit the 2017 November/December issue page

To read more ALTC expert commentary and news, visit the homepage

References

1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). State operations manual Appendix PP -Guidance to surveyors for long term care facilities. CMS website. https://cms.hhs.gov/manuals/Downloads/som107ap_pp_guidelines_ltcf.pdf. Published February 6,

2015. Accessed November 13, 2017.

2. Smith PW, Bennett G, Bradley S, et al. SHEA/APIC guideline: infection prevention and control in the long-term care facility, July 2008. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36(7):504-535.

3. Strausbaugh LJ, Joseph CL. The burden of infection in long-term care. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2000;21(10):674-679.

4. Nicolle LE. Preventing infections in non-hospital settings: long-term care. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(2):205-207.

5. Rogers MA, Mody L, Chenoweth C, et al. Incidence of antibiotic-resistant infection in long-term residents of skilled nursing facilities. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36(7):472-475.

6. World Health Organization (WHO). Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance 2014. WHO website. https://www.who.int/drugresistance/documents/surveillancereport/en. Published April 2014. Accessed November 13, 2017.

7. White House. National action plan for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria. White House website. https://www.whitehouse.govhttps://s3.amazonaws.com/HMP/hmp_ln/imported/docs/national_action_plan_for_combating_antibotic-resistant_bacteria.pdf. Published March 2015. Accessed November 13, 2017.

8. van Buul LW, van der Steen JT, Veenhuizen RB, et al. Antibiotic use and resistance in long term care facilities. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(6):568.e1-e13.

9. Mitchell SL, Shaffer ML, Loeb MB, et al. Infection management and multidrug-resistant organisms in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1660-1667.

10. Slayton RB, Toth D, Lee BY, et al. Vital signs: estimated effects of a coordinated approach for action to reduce antibiotic-resistant infections in health care facilities-United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(30):826-831.

11. High KP, Bradley SF, Gravenstein S, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the evaluation of fever and infection in older adult residents of long-term care facilities: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(2):149-171.