Prepping for Take Off: Readying Older Adults for Air Travel

As adults continue to travel great distances by plane well into old age and despite comorbidities, geriatric providers should be well versed in how to prepare these older individuals for air travel. As unplanned landings are uncommon in cases of medical emergencies, factors such as aircraft personnel medical training and volunteer traveling providers should be considered. The unique environment of airplane cabins and the limited communication and equipment options during flights are also important factors for providers to keep in mind when performing individual preflight assessments on older adults before travel. Authors review these concerns and provide recommendations for providers to consider, so that older individuals with medical conditions can travel safely and comfortably.

Key words: Alzheimer disease, air travel, TSA, FAA, medical travel companion

The potential for medical issues and complications for older adults while traveling is growing; this is due to increased access to and demand for far flung travel1 combined with an explosion in the number of older adults, some of whom are still travelling well into old age2 despite frailty and comorbidities. From 2002 to 2005, studies show that the rate of in-flight deaths doubled.3 This is consistent with a study that reported that the rate of medical emergencies on commercial flights nearly doubled between 2000 and 2006, from 19 to 35 emergencies per 1 million passengers.4 Avoiding an in-flight medical emergency is critical not only for the patient but also in relation to the expense and danger for the airlines; thus, all parties involved bear some responsibility, from the patient and family to the community providers and airlines.

Travel preparation is necessary because older adults and medical professionals cannot rely on aircraft diversion or unplanned landings in emergency medical cases. The decision to divert an aircraft is not to be made lightly, as it can cost in excess of $100,000.3 In addition, the diverted aircraft may sustain damages, such as blowing tires during landing because of being overweight from excess fuel. Because diversion can be costly, and since most onboard medical emergencies are relatively uncommon and typically not life-threatening,5 it is uncommon for an aircraft to be diverted, with the diversion rate estimated to be between 8% and 13% of all in-flight medical emergencies.6

The decision to divert an aircraft is ultimately the aircraft captain’s decision, but the captain will likely follow the physician’s recommendation, perhaps with additional input from the ground medical team. Oftentimes, ground medical services are being provided by MedAire, Inc,7 a company that provides 24-hour medical assistance, training, and medical kits to international jet manufacturers and major airlines. MedAire operates a system called the MedLink Global Response Center, which provides onboard physicians with direct call access to emergency care physicians and to other services for managing inflight medical emergencies. MedLink has reported managing 19,000 calls for help annually from its call center, based within the emergency unit of the Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center in Phoenix, AZ.7

Yet, despite the availability of services such as MedLink, air-to-ground communication is difficult. This is primarily because many airlines have removed phones from cabins and secured cockpit doors following the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. Today, information is usually relayed by intercom from the cabin to the pilots, who then pass it along to MedLink on the ground. It has been reported that some airlines are using satellite radios on flights over the Pacific Ocean, putting headsets in the cabin so that flight attendants can directly communicate with physicians on the ground.4

In addition to those general airline considerations, on-board personnel and environment on the plane itself is a concern. For example, airline and special assistance personnel are not permitted to assist passengers with activities of daily living, increasing the risk for injuries, such as falls in restrooms. Restrooms within the airplane itself are small and most often do not provide grab bars. Special assistance personnel can wait outside of the restroom with a wheelchair while the traveler walks unassisted into the restroom, or the traveler is required to self-propel. For these reasons and others, traveling alone for frail older adults can be a challenge.

Older adults looking to travel should take advantage of the opportunity to properly prepare. It is therefore vital for a variety of geriatric health care providers to be well versed in medical preparation strategies and be aware of the multiple ways that traveling by plane impacts medical options. Ideally, health care professionals’ primary goal should be to prevent medical problems from occurring, so that everyone can enjoy a safe trip. But, practically speaking, there are always instances of unavoidable and unforeseen incidents, thus professionals should also be aware of how medical issues are routinely handled on planes, and travelling physicians should be ready to respond to medical emergencies while in flight. In the following review, a variety of considerations will be discussed, including use of companies offering medical travel companions/assistance, what medical equipment is readily available on aircraft, and how to prep older individuals based on probable medical risks.

Medical Travel Companions

Assistance for older adult travelers is available in the form of several organizations who specialize in providing travel assistance to older adults. Many of these groups provide affordable door-to-door companion services for medically stable individuals unable to travel alone using commercial transportation options. The starting point for this travel assistance can be directly following a discharge from a hospital, skilled-nursing facility, long-term care, assisted-living facility, or other retirement community, or simply from a private residence. The coordination of these flights—typically for relocation rather than vacation—can sometimes take weeks to plan to ensure both the safety of the traveler as well as the safety of other airline passengers.

Moreover, this assistance is available to both prep the frail older adult for travel as well as directly assist during travel. Agency provider teams start by evaluating each individual’s travel needs, then they design a personalized care plan to limit the amount of stress for both the traveler and their family. Both family and/or friends are actively involved in the planning process. For example, in travelers known to have a history of behavioral expressions, preparations may include identifying techniques and approaches that will limit the need for medication and the risk of flight crew concerns during the actual flight. Nurses can assist in the management of chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, congestive heart failure (CHF), etc, including the maintenance and care of peg-tubes, Foley/suprapubic catheters, medications, oxygen, and small-volume nebulizers. Travel assistants’ expertise can also include the understanding of rules and regulations, allowing the travel care team to provide assistance in required transition documentation. Communication between the discharging and receiving facilities and family is vital in ensuring a smooth transition.

Aircraft Environmental Factors

Before thinking about how to prep older adults for travel, it is important to know how aircraft environments can impact traveling older adults. For example, unlike an emergency situation in a public space on the ground, access to support via 911 and other emergency responders as well as availability of a spacious and stable workspace are vastly limited on an aircraft. Care in aircraft is also unique in the types of disease manifestations and physiological changes that can result while in-flight. According to the Aerospace Medical Association (AsMA) Medical Guidelines for Airline Travel, the cabin pressure at cruising altitude is set to between 5000 and 8000 feet above sea level, which presents two issues for providers to consider: gas trapped in body cavities and hypoxia.8 Gas trapped in body cavities at sea level will expand by approximately 25% at cruising altitude.9 This may exacerbate such conditions as pneumothorax, pneumocranium, or middle-ear pain for passengers with preexisting risk factors. In terms of hypoxia, at cruising altitude, all passengers experience some degree of hypoxia. This is the result of the fact that barometric pressure is 760 mm Hg at sea level, with a corresponding partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2) level of 98 mm Hg, whereas the barometric pressure is 565 mm Hg, with a PaO2 of about 55 mm Hg at the typical cabin pressure of 8000 feet.8 If these data were to be plotted on the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve, a 90% oxygen saturation level would be obtained.8 Although most healthy travelers can compensate for this amount of hypoxia, this may not be true for some older adults who have a cardiopulmonary disease or anemia.

Onboard Medical Equipment

The topic of environmental concerns naturally leads to questions on the availability of medical equipment on aircraft, such as diagnostic and treatment resources—resources providers may take for granted as being available based on typical ground emergencies. For instance, a passenger experiencing a potential medical emergency, such as those mentioned above, would benefit from supplemental oxygen. Many airlines will provide therapeutic oxygen for a small fee, but these arrangements need to be made in advance of travel and are especially important for those older adults requiring supplemental oxygen when not traveling. Since travelers are not permitted to carry their own oxygen onto flights, obtaining it through the airline is the only option. Individuals requiring continuous oxygen should be cautioned that airlines only provide oxygen in-flight; thus, arrangements should be made if continuous oxygen is required.

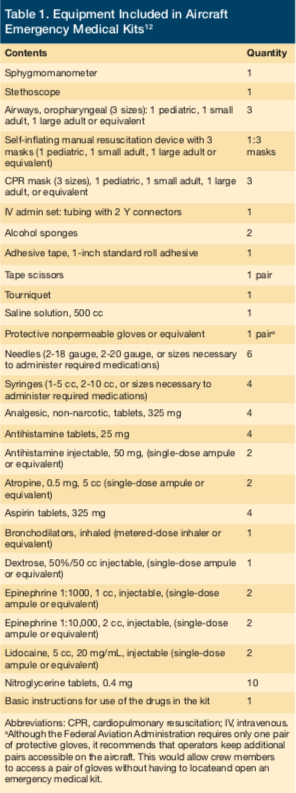

While oxygen can be prearranged to be included on some flights, other medical equipment is standard on aircraft. The Aviation Medical Assistance Act of 199810 set out to direct the administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to reevaluate the equipment contained in medical kits carried by commercial airlines and to make a decision regarding requiring automated external defibrillators (AEDs) to be included.10 On April 12, 2001, in response to the Act, the FAA issued a final rule requiring airplanes that weigh more than 7500 lb and that have at least one flight attendant must have AEDs and enhanced emergency medical kits.11 The enhanced emergency medical kit has been developed to facilitate provision of emergency care for passengers by individuals with rudimentary emergency training, ensuring adequate and appropriate care is provided even in the absence of an experienced health care professional. Before the FAA’s final ruling, the only medication required onboard by the FAA was 50% dextrose, nitroglycerin, diphenhydramine, and epinephrine. For a list of items that emergency medical kits are currently required to contain, see Table 1.12

Although AEDs are part of the emergency medical kit, many airlines require that only their trained crew operate these devices to ensure continuity of protocols. When use of an AED is required onboard, volunteer physicians should work to complement the skills of the trained crew. Although used infrequently, the presence of these devices on flights is essential because they can have a dramatic impact on outcomes. The effectiveness of AEDs in-flight is described in a study by Page and colleagues.13 The authors report that between June 1, 1997 and July 15, 1999, one US airline carrier used an AED on 191 passengers inflight and on nine people in an airport terminal, meaning the device was used once for every 3288 flights by this carrier. Transient or persistent loss of consciousness was documented in almost 50% of these passengers, with the remaining persons having needed the device primarily because of chest pain. Ventricular fibrillation was electrocardiographically documented by the AED in a total of 14 individuals, and the device terminated every episode with the first shock in 13 of these individuals (defibrillation was withheld in one individual per the family’s request). The rate of survival after defibrillation to discharge from the hospital was 40%, which compares favorably with the rate of survival to discharge among patients who received a defibrillator shock in other out-of-hospital settings.13 Perhaps the most important point for physicians to consider is that AEDs have been found to be safe when used as a monitor, and in no case in that study13 was an inappropriate shock recommended or delivered.

Onboard Medical Personnel and Assistance

It is helpful to be aware of laws related to volunteer travelling physicians on aircraft and the likelihood that these physicians may be on board in the event of a medical emergency. In a 1991 FAA study, physician travelers were available in 85% of reported inflight medical emergencies.14 Despite this availability, though, many physicians remain confused about the related laws. To begin, the regulations governing any event happening on an aircraft is usually based on the law of the country in which the aircraft is registered, except when the aircraft is on the ground. For the United States, physicians on aircraft are described in the Aviation Medical Assistance Act of 1998; the Act includes provisions limiting the liability of volunteer physicians who attempt to assist with in-flight medical emergencies due to previous instances in which airlines faced litigation when the advice of passenger doctors was deemed incorrect.10

As noted above, airlines consider physicians who respond to calls for assistance as volunteers, and as such, passenger physicians complement the flight crew rather than override them. Thus, the physician is not expected to perform duties that the flight crew is trained to handle. Cabin crew receive training in a number of emergency skills, including use of AEDs and are one of several sources of help available to the medical volunteer, who is not expected to work alone. Because only qualified persons can administer drugs, the flight crew may ask for identification to verify credentials, such as a business card or wallet medical card. In addition, while physicians are not obligated to volunteer, the World Medical Association International Code of Medical Ethics states: “A physician shall give emergency care as a humanitarian duty unless he/she is assured that others are willing and able to give such care.”15 Still, being overprepared and having one’s own medical assistance instead of relying on the luck of having a willing and able physician onboard is definitely preferred.

Preparing Patients for Travel

Once providers fully understand the roles that environment, equipment, and personnel play during aircraft travel for older adults, they can direct more attention to what preparations may be needed on an individual basis. Prevention starts with the health care provider assessing and advising his or her older patients with regard to any preflight medical needs. According to AsMA, there are many medical conditions that should be addressed in a preflight medical evaluation, including cardiovascular diseases (eg, angina pectoris, CHF, myocardial infarction [MI]), deep venous thrombosis (DVT), asthma, emphysema, seizure disorder, stroke, mental illness, diabetes, infectious diseases, and conditions for which the patient has undergone recent surgery or that require surgery.8

Previous research provides some insight on what may be the more common types of in-flight medical emergencies to consider. The Flight Safety Foundation published a study in 2000 on in-flight medical care aboard selected US air carriers from 1996 to 1997 and recorded 1132 medical incidents, of which 22.4% were caused by vasovagal syncope, 19.5% by cardiac events, and 11.8% by neurologic events.16 In contrast, another study (also published in 2000) of in-flight emergencies on British Airways flights reported a different pattern of diagnoses, finding that 25% were related to gastrointestinal problems and fewer than 10% each were from cardiac, neurologic, or vasovagal issues.17 A more recent study found that vasovagal syncope (a temporary loss of consciousness) is the most common in-flight emergency.18 In an even more recent MedAire study, passengers with diabetes, seizure disorders, and cardiovascular and respiratory ailments accounted for approximately 25% of all in-flight deaths and almost 33% of medically related flight diversions.4

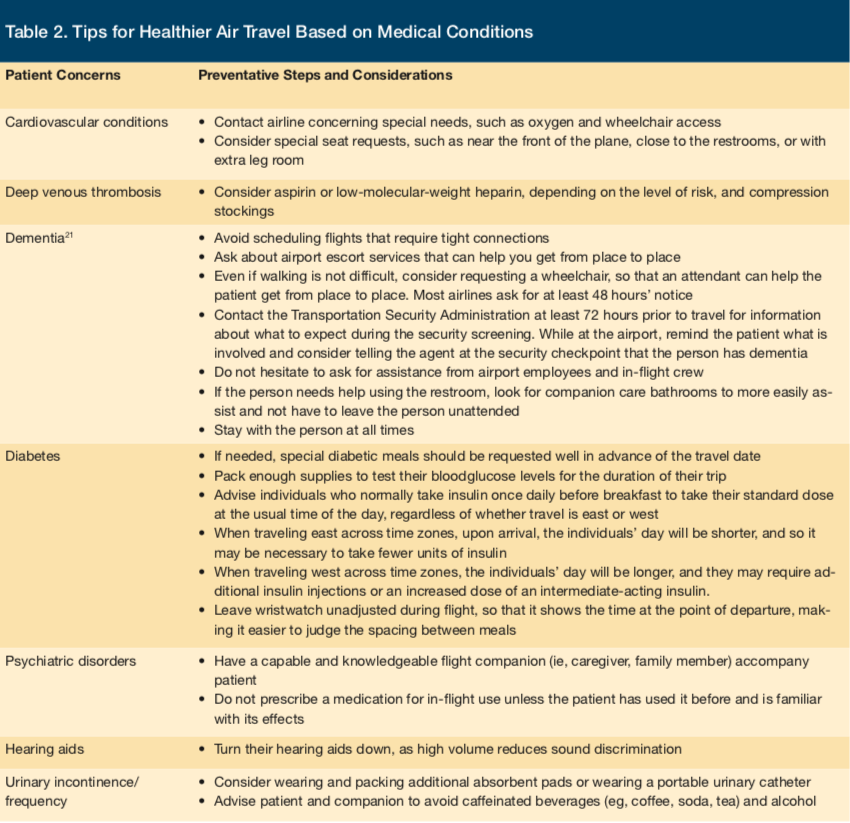

Studies are helpful during the preparation process, but it is imperative that providers remember to consider older adults’ individual medical concerns. Nonetheless, to account for these findings, a few of these reportedly more common medical issues are discussed at length below, including a discussion of patients traveling with dementia. An easy-to-read list of air travel precautions and tips for these common issues and others can be found in Table 2.

Patients at Risk of Cardiovascular Events

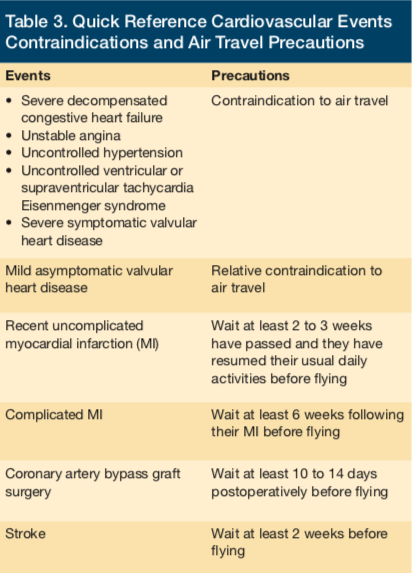

Providers should advise their patients who have had a recent uncomplicated MI not to fly until at least 2 to 3 weeks have passed and they have resumed their usual daily activities.8 In contrast, patients who have had a complicated MI should not fly for at least 6 weeks following their MI; those who have undergone coronary artery bypass graft surgery should not fly before 10 to 14 days postoperatively; and those who have had a stroke should wait at least 2 weeks before traveling by air.8 Cardiovascular conditions that present a contraindication to air travel include severe decompensated CHF, unstable angina, uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled ventricular or supraventricular tachycardia, Eisenmenger syndrome, and severe symptomatic valvular heart disease. Mild asymptomatic valvular heart disease presents a relative contraindication to air travel. A quick-reference for these conditions and contraindications can be found at Table 3.

According to the AsMA, providers should make several travel recommendations for their patients with cardiovascular conditions, one of which is that they carry enough cardiac medication for their entire trip, including sublingual nitroglycerin tablets, and keep these medications in their carry-on luggage.8 Another recommendation is that patients keep a list of their medications, including dosage and timing, and adjust dosing intervals to maintain their regular frequency when crossing time zones. Additionally, patients should carry a copy of their most recent electrocardiogram and their pacemaker card if they have a pacemaker. Generally, it is advisable for patients to contact their airline concerning special needs, such as oxygen and wheelchair access, and to consider special seat requests, such as near the front of the plane, close to the restrooms, or with extra leg room.

Patients at Risk of DVT

Special precautions may be needed for older adults at high risk of developing a DVT, especially if there will be prolonged immobilization due to a long flight (> 6 hours).8 Although DVT itself is not a dangerous condition, it can have life-threatening complications such as pulmonary embolism or venous thromboembolism. There are numerous factors besides a patient’s age that may put him or her at risk of developing a DVT. These risk factors include blood disorders that affect clotting tendency, cardiovascular diseases, current malignancy or history thereof, recent major surgery or trauma to the lower limbs or abdomen, and a personal or family history of DVT. For such individuals, possible preventive options include taking aspirin or low-molecular-weight heparin, depending on the level of risk, and wearing compression stockings.

Patients With Diabetes

Although airline travel should not pose a significant problem for patients whose diabetes is normally well controlled, proper preparation remains beneficial. Besides recommending that diabetic patients pack enough supplies to test their bloodglucose levels for the duration of their trip, providers can make other specific recommendations to their patients.8 For example, they should advise individuals who normally take insulin once daily before breakfast to take their standard dose at the usual time of the day, regardless of whether travel is east or west. For diabetic individuals traveling east across time zones, upon arrival, the individuals’ day will be shorter, and so it may be necessary to take fewer units of insulin. While traveling west across time zones, the individuals’ day will be longer, and they may require additional insulin injections or an increased dose of an intermediate-acting insulin. It is a good idea for individuals with diabetes to have their wristwatch unadjusted during flight, so that it shows the time at the point of departure, making it easier to judge the spacing between meals. Also, if needed, special diabetic meals should be requested well in advance of the travel date.

Patients With Psychiatric Disorders

Persons with psychiatric disorders that can lead to unpredictable or aggressive behaviors should not travel by air until these behaviors are well controlled, as these individuals can pose a danger or be disruptive to others onboard, not just themselves. Specifically, patients with a psychiatric disorder can become upset by the common irritations of travel, such as crowding with strangers, lack of privacy, and delays.8 If a patient with a psychiatric disorder, such as dementia, must travel by air, a capable and knowledgeable flight companion (ie, caregiver, family member) should accompany them. Providers can offer the patient, and their travel companion, several travel recommendations.8 For example, since patients with dementia often experience sundowning syndrome (ie, an increase in abnormal behaviors at a certain time of the day, typically in the late afternoon, evening, or night), the timing of flights should be taken into account so the patient can avoid being in the air during this time. As for prescribing a medication to a patient to assist with behavior, it has been recommended that one never prescribe a medication for in-flight use unless the patient has used it before and is familiar with its effects. Obviously, during a flight is no time to discover an untoward medication reaction.

Patients With Less Complex Disorders

Providers can also make useful recommendations to ensure the comfort of their traveling geriatric patients with disorders that are not potentially dangerous to fly with but can pose a nuisance, such as hearing impairment and urinary frequency or incontinence. Patients with hearing aids may become frustrated by their decreased ability to hear in-flight due to background noise in the cabin. These patients should be advised to turn their hearing aids down because high volume reduces sound discrimination. As for those with urinary frequency or incontinence, an aisle seat, preferably close to the restrooms, is advised. If the patient’s urinary frequency is related to a medication, such as a diuretic, dose adjustments may be warranted. Patients with urinary incontinence may consider wearing and packing additional absorbent pads or wearing a portable urinary catheter. Although it is important for patients to stay hydrated during their flight, they should be reminded that not all beverages are created equal. Water is the best choice. Caffeinated beverages (eg, coffee, soda, tea) and alcohol are diuretics and can aggravate an already overactive bladder; thus, these should be avoided.

Patients With Dementia In-flight and at Airports

Although dementia is mentioned briefly above, it should be given more attention considering the prevalence of dementia with the rising older adult population. There are over 5 million Americans with Alzheimer disease (AD) alone (this number does not include those with any indication of cognitive impairment), and that number is expected to increase to 16 million by 2050.19 As a result, the aviation industry has identified AD as the fastest growing concern for both airports and airlines.20 Despite this fact, flight crews are only trained to ensure the safety of the aircraft during flight, they do not have a broader understanding of dementia or specific training, making disorientation, hallucinations, wandering, and aggression a true concern. Some recommendations21 for patients flying with dementia include making sure the patient has a companion at all times and requesting a wheelchair to make movement easier and faster (most airlines need at least 48 hours’ notice for this request). Companions traveling with patients with dementia should also not hesitate to request assistance from airport employees and flight crews.

Moreover, the number of reports of individuals wandering away from gates and/or airports has increased,22 yet Transportation Security Administration agents are not trained to manage travelers with memory impairment during screening. Airlines have described their responsibility as simply escorting passengers requesting assistance through security to the gate or to an airlines transfer desk where they may wait on their own. The airline staff cannot stay with the passenger at all times or guarantee supervision at all points of the journey.

Conclusion

Due to the complex factors related to older adults traveling with medical conditions, medical providers, family members, and any other health care professionals who work in the geriatric field should take great care in making preparations for older adults who will be traveling. The safety of other passengers, legal liability concerns, and financial consequences to airlines are all important reasons in support of thorough preparations, not to mention the individual health, safety, and comfort of the traveling older adult.

For additional information on preparing older adult patients for air travel, there are two especially helpful resources that have been prepared by AsMA: Medical Guidelines for Airline Passengers,14 referenced above, and Health Tips for Airline Travel,23 which are both available through their website at www.asma.org.

References

1. US Department of Transportation (DOT) Research and Innovative Technology Administration (RITA). Passenger Travel Facts and Figures 2014. US DOT website. https://www.rita.dot.gov/btshttps://s3.amazonaws.com/HMP/hmp_ln/imported/PassengerTravelFactsFigures.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2017.

2. Pearce B, International Air Transport Association (IATA). The shape of air travel markets over the next 20 years. IATA website. https://www.iata.org/whatwedo/Documents/economics/20yearsForecast-GAD2014-Athens-Nov2014-BP.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2017.

3. Cocks R, Liew M. Commercial aviation in-flight emergencies and the physician [published correction appears in Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19(3):286]. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19(1):1-8.

4. Davis R, DeBarros A. In the air, health emergencies rise quietly. USA Today. March 11, 2008. www.usatoday.com/news/health/2008-03-11-inflight-medical-emergencies_N.htm. Accessed August 22, 2017.

5. DeLaune EF III, Lucas RH, Illig P. In-flight medical events and aircraft diversions: one airline’s experience. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2003;74(1):62-68.

6. Gårdelöf B. In-flight medical emergencies. American and European viewpoints on the duties of health care personnel [in Swedish]. Lakartidningen. 2002;99(37):3596-3599.

7. MedAire. Medical Advisory Services: MedLink. MedAire website. https://www.medaire.com/airlines/solutions/medical-advisory-services-medlink. Accessed September 15, 2017.

8. Aerospace Medical Association Medical Guidelines Task Force. Medical guidelines for airline travel, 2nd ed. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2003;74(suppl 5):A1-A19.

9. Porter RS, Kaplan JL, eds. Air travel: medical aspects of travel. The Merck Manual Online. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/special-subjects/medical-aspects-of-travel/air-travel. Accessed August 22, 2017.

10. Aviation Medical Assistance Act of 1998, HR 2843, 105th Cong (1998). www.medaire.com/FAA_OnboardMedicalKits_pl105170.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2017.

11. FAA requires airlines to carry heart device [news release]. Washington, DC: US Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration; April 12, 2001. www.faa.gov/news/press_releases/news_story.cfm?contentKey=1262. Accessed August 22, 2017.

12. US Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration. Emergency medical equipment. Advisory Circular No. 121-33. https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/AC121-33B.pdf . Accessed August 22, 2017.

13. Page RL, Joglar JA, Kowal RC, et al. Use of automated external defibrillators by a US airline. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(17):1210-1216.

14. Hordinsky JR, George MH; US Department of Transportation. Utilization of Emergency Kits by Air Carriers. Washington, DC: Office of Aviation Medicine; March 1991. https://bit.ly/EmergencyReport. Accessed August 22, 2017.

15. World Medical Association (WMA). WMA International Code of Medical Ethics. National Institutes of Health website. https://history.nih.gov/research/downloads/icme.pdf. Published 1949. Accessed September 15, 2017.

16. DeJohn C, Veronneau S, Wolbrink A, Larcher J, Smith D, Garrett JS; Flight Safety Foundation. Evaluation of in-flight medical care aboard selected US air carriers: 1996-1997. Cabin Crew Safety. 2000;35(2):1-19.

17. Dowdall N. “Is there a doctor on the aircraft?” Top 10 in-flight medical emergencies. BMJ. 2000;321(7272):1336-1337.

18. Qureshi A, Porter KM. Emergencies in the air. Emerg Med J. 2005;22(9):658-659.

19. Alzheimer’s Association (AA). 2017 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. AA website. https://www.alz.org/facts/. Accessed September 8, 2017.

20. Castiglioni R. Flying with dementia growing challenge in aviation industry. Reduced Mobility Rights LLC website. https://www.reducedmobility.eu/20130327298/The-News/flying-with-dementia-growing-challenge-in-aviation-industry.html. Published March 27, 2013. Accessed September 15, 2017.

21. Alzheimer’s Association (AA). Traveling with dementia. AA website. https://www.alz.org/care/alzheimers-dementia-and-traveling.asp. Accessed September 15, 2017.

22. Alzheimer’s Association (AA). Wandering and getting lost. AA website. https://www.alz.org/care/alzheimers-dementia-wandering.asp. Accessed September 15, 2017.

23. Aerospace Medical Association (AsMA). Health Tips for Airline Travel. AsMA website. https://www.asma.org/asma/media/asma/Travel-Publications/HEALTH-TIPS-FOR-AIRLINE-TRAVEL-Trifold-2013.pdf. Accessed September 8, 2017.