Post-Hospital Transitions for Individuals With Moderate to Severe Cognitive Impairment

When caring for individuals with cognitive impairment, recommended targets for quality improvement include the overall health of this population, the individual experiences of cognitively impaired individuals, and the costs associated with treatment.1 Persons with advanced dementia are at risk for burdensome transitions between institutions, with transitions from medical or psychiatric inpatient care facilities to home care or to other care facilities being of particular concern.2-4 The cost of dementia care is high, with inpatient hospital treatment being the most expensive. Alzheimer’s disease, the most prevalent type of dementia, is the fifth leading cause of death for Americans older than 65 years, and the death rate has been rising as other major causes of death, such as heart disease and stroke, have been decreasin.5 An estimated annual expenditure of $148 billion is attributable to Alzheimer’s disease, not including $94 billion in uncompensated services that are provided by family caregivers.5 Half of the total dementia-related Medicare costs are spent by only 10% of Medicare beneficiaries who have dementia.6 The driving factors in the high use of healthcare services by individuals with dementia are inpatient and emergency treatments.6,7 Efforts are underway to track services used by dementia patients and to determine best practices for improving their overall care and quality of life while containing costs.8,9 Included costs to consider are inpatient admissions, not only to medical hospitals, but also to psychiatric units for the management of dementia-related behavioral disturbances.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

RELATED CONTENT

Persistent Delirium Secondary to Lithium Toxicity in a Patient with Dementia Due to Traumatic Brain Injury

Study Shows Late-Life Depression Increases Risk of Future Cognitive Impairment

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Cognitive Impairment and Hospitalization

In the last months of life, many individuals with advanced dementia experience burdensome interventions, including hospitalization.2 Individuals with severe dementia who receive complex inpatient treatment have a longer length of inpatient stay.10 For elderly psychiatric inpatients, cognitive functioning predicts overall functioning, and social factors, including family functioning, predict rehospitalization rates.11-13 Among Medicare beneficiaries, psychotic disorders comprise the second highest rate of 30-day rehospitalization (24.6%), just behind heart failure (26.9%).14 In addition to individual factors, hospitalizations in patients with dementia are predicted by health system factors, including local and regional patterns of available care options.15

For individuals with cognitive impairment identified before hospitalization, poor comprehension of discharge instructions by patients and caregivers increases the risk of medical rehospitalization.3,16,17 Other risk factors for rehospitalization are in the process of being defined. In a recent solicitation for demonstration project applications, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services stated interest in improving post-hospital transitions for individuals with “multiple chronic conditions, depression, cognitive impairments, or a history of multiple admissions.”18 Similarly, the current draft of the National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease under the federal government’s new National Alzheimer’s Project Act proposes improving hospital transitions and other care transitions as a core strategy for enhancing care quality.19

Issues and Challenges in Care Transitions

A transition of care occurs when a patient relocates to a new environment to receive healthcare. Interest in transitions has focused on care quality, particularly during the hand-off from inpatient treatment to immediate hospital aftercare. The number of hand-offs is considered to be a major factor in determining quality of transitional care and rehospitalization rates, with each hand-off increasing the likelihood of poor transitional care and rehospitalization.

In recent years, the average length of inpatient hospital care has decreased, but there has been an increase in rehospitalization rates.8 This can be partly attributed to increased fragmentation and reduced continuity of care in the healthcare system. Primary care doctors may not know all the details of a specific hospitalization because current patient care is often delivered by hospitalists who may not have been previously involved in the patient’s primary care. Medical inpatient treatment by hospitalists compared with primary care clinicians may reduce hospital length of stay and hospital costs up front, but this approach is also associated with increased post-hospital costs, including greater use of medical services and increased rehospitalization rates.20 Better communication between the hospitalist and the primary care doctor will equip both parties with the information needed to provide quality care during transitions from one care setting to another.

Renewed attention to factors such as length of hospital stay, cost, and better care coordination is clearly evident in the emphasis on care transitions in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), including specific provisions intended to reduce the incidence of rehospitalization.8 The process and outcome of the response to the PPACA will be important for institutions, payers, and individual patients. Potential difficulties exist at the regional level, including communication and infrastructure barriers, as well as mismatches between the need for services and their availability. On a case-by-case basis, individual patients and family members do not always have access to all the information needed to make informed choices about discharge and aftercare options.21 Planning post-hospital care is more complicated for individuals with dementia than for cognitively intact individuals. The complexity of aftercare planning for patients with dementia increases their risk of rehospitalization.

After hospital treatment for a medical condition, cognitively impaired individuals often have limited ability to participate in discharge planning and to follow aftercare instructions. If a family caregiver is available, he or she may be able to assist with discharge plans and follow-up; in this situation, it is important to determine which family member is best suited to aid with discharge planning.22 Patients who had minor or no cognitive impairment before hospitalization, but who experienced acute delirium during inpatient treatment, may poorly recall elements of their medical care, making it more difficult for these individuals to plan and manage their aftercare needs despite an apparent return to baseline functioning. Another contributing factor to consider is depression; elderly individuals with depression undergoing medical or psychiatric inpatient treatment also require enhancements in discharge planning to prevent rehospitalization.23

When dementia-related acute behavioral disturbance is prominent during hospital care, aftercare services can be cumbersome to arrange and implement for the following reasons: (1) individuals with dementia experience complex inpatient treatment; (2) cognitive impairment limits the individual’s ability to participate in discharge planning; (3) dementia-related behaviors may result in active resistance to components of the post-hospital plan; (4) in-hospital improvement in behavior may be partly due to psychosocial or environmental interventions rather than to pharmacotherapy, and translating these gains may require enhanced communication; (5) comorbid medical and psychiatric care needs may require many specialty consultations; (6) regional practice patterns and institutional policies may introduce barriers regarding access to aftercare services; and (7) family caregivers often lack the time, money, and the cognitive or emotional resources to triage tasks and solve problems about new dilemmas.10,24 Despite these potential barriers, evidence from interventions with cognitively intact individuals suggests that attention to transitional care for people with dementia can lead to improved outcomes.

Efforts to Reduce Rehospitalization Rates

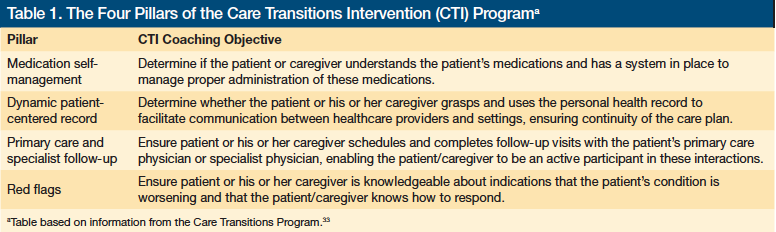

Several post-hospital transition programs have demonstrated the potential to reduce rehospitalization rates and lower costs for medical patients.25-30 The focus of these programs has been the medical discharge and hand-off communication process. A variety of intervention strategies have been tested, all directed toward the goal of improving communication and enhancing engagement in healthcare follow-up. For example, the coaching approach developed by Coleman31 as the Care Transitions Intervention (CTI) can be successfully implemented across hospitals to improve regional health care.32 The CTI involves a trained “transition coach” who performs a hospital visit, a home visit, and follows up with the patient and family via telephone. During each contact point, the CTI coach provides patients with hospital-discharge guidance that addresses four conceptual areas, which are referred to as the “Four Pillars” (Table 1).33 Recently, tailored aftercare services have started focusing on the comprehension of discharge instructions and other vulnerabilities that individuals with cognitive impairment and their caregivers may experience following medical hospitalization.10,34,35 While programs such as the CTI are now incorporating family caregivers and addressing special procedures for individuals with mild or moderate cognitive impairment, limitations in the current evidence persist because most intervention studies have excluded individuals with severe cognitive impairment, and minimal attention has been directed toward the discharge process from inpatient psychiatric treatment facilities.24

Exploring Newer Approaches

There is growing awareness that cognitive impairment may complicate the hospital discharge process and transition to post-hospital care settings.35 Naylor3 is investigating a transition program for individuals with cognitive impairment who are discharged from medical hospitalization to home. Meanwhile, hospitals and healthcare systems are implementing quality improvement programs that adopt best practices, including attention to individuals with cognitive impairment. Examples of such programs are Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults Through Safe Transitioning) from the Society of Hospital Medicine, and Project RED (Re-Engineered Discharge) from the Boston University Medical Center.36-39

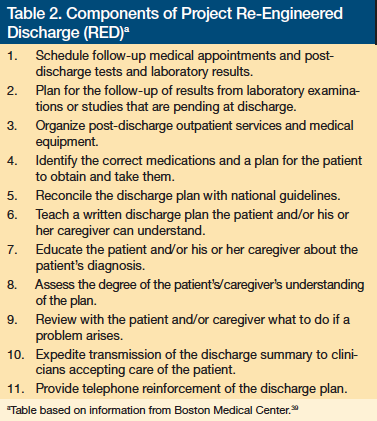

Project BOOST aims to identify high-risk older adults on admission and targets risk-specific interventions to reduce 30-day readmission rates and hospital length of stay. Improving facility patient satisfaction and information flow between inpatient and outpatient providers are additional goals. Applications to become a BOOST site are available online.36 Project RED outlines specific components for improving hospital discharge plans that will smooth transitions for all patients. These components are outlined in Table 2.39

Select psychosocial programs are being developed to improve transition to nursing homes, although these do not focus on hospitalization risk.40 Care management interventions for dementia patients treated in the primary care setting have shown positive outcomes.41 These programs have been designed for relatively stable outpatients, but may offer insight on how to focus an intervention specifically for post-hospital care.42 The transition from inpatient psychiatric treatment remains an understudied area, which may be complicated by the unique quality of inpatient standards of psychiatric care.25,43 Fortunately, model programs for such transitions are under development.44,45

Pharmacotherapy Considerations

Pharmacotherapy for dementia-related behaviors has been scrutinized. Mounting concerns about the risks and benefits suggest that medications, particularly antipsychotics, should be used only in severe situations and under careful monitoring, with a plan for trial discontinuation after short-term use.46-50 In contrast, specific medications have shown lesser risk51; however, ultimately, the choice regarding pharmacotherapy for dementia should be individualized for every patient, taking into consideration the specific target behaviors, the patient’s medical vulnerabilities, the side-effect profile of the medication, and the patient’s and family’s wishes regarding advanced care planning and quality of life. Given the medical vulnerability of the cognitively impaired elderly, increased attention could be directed to psychosocial treatments that have demonstrated benefits and few risks (eg, individualized personal contact, sensory-focused strategies using music or multisensory stimulation, caregiver interventions), although testing of such treatments in acute medical settings has been limited.52-55 The process of obtaining informed consent for a hospital treatment or new medication can be an opportunity to assess a patient’s and family’s available resources, and assist them with adjusting to continued functional decline as dementia symptoms advance.

Patient and Caregiver Burdens

Because dementia is a terminal disease,2 exposing individuals with severe dementia to hospital services and other burdensome interventions that are unlikely to result in clinical improvement or reduce suffering (eg, feeding tube placement) should be avoided.4,56 Reports regarding end-of-life care in dementia suggest that orders such as “do not hospitalize” are uncommon, and the presence of such a directive is related to individual patient, regional, and institutional factors.57 Discussions regarding serious decisions, such as on feeding tube placement and do-not-hospitalize orders, can be undertaken during routine patient care and are important to educate the patient and his or her family caregivers so that an informed decision can be made.58

For some family members, grief and other symptoms similar to bereavement may begin before the patient dies.59 Family caregivers of an individual hospitalized for dementia are also at heightened risk for depression.60,61 In general, caregivers report worse health than noncaregivers, engage in fewer health-promoting behaviors, and have worse medication adherence.62-64 In 1999, Schulz and Beach65 reported a 63% higher mortality risk for stressed spousal caregivers. Further data regarding mortality risks suggest that caring for a hospitalized patient is an independent risk factor for spousal caregiver death; dementia caregivers have the highest risk, possibly related to poor self-care, the distress of facing dementia-related behavioral problems in their loved one, or worries about making end-of-life decisions.66-68 In these situations, attending to caregiver health concerns amid discussions of dementia treatment for the patient can be helpful.

The Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement and Recommendations

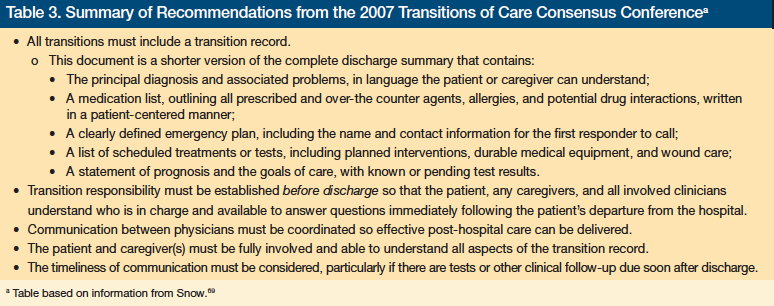

Broad recommendations regarding post-hospital transitions were defined during the 2007 Transitions of Care Consensus Conference (TOCCC) and subsequently published.69 The report, which draws on results from intervention studies and clinical expert opinion, supports continued development and dissemination of evidence-based practices. The policies described in the TOCCC report are designed to apply to the transition from inpatient medical treatment to outpatient care at home. Despite the focused nature of the guidelines, the general principles can be applied to other transitions, including those experienced by individuals with dementia or delirium undergoing discharge from medical and psychiatric hospitals to home, to a nursing home, or to an assisted living facility.

General recommendations from the TOCCC report are outlined in Table 3. The standard transition record, for any individual being discharged from a medical hospital, should be fully understandable by the patient or his or her caregiver and incorporate the listed items. The clinician

completing the transition record should clearly document his or her name and institutional affiliation; knowledge regarding the patient’s advance directives, if any; the patient’s capacity to understand information; and the status of any caregivers who are assisting the patient.69 Medical communities as well as hospital and healthcare institutions should consider adopting national standards similar to those recommended in the TOCCC report; tool kits to aid success are available through programs such as projects BOOST and RED.

Tailoring the Transition Record for Moderate to Severe Cognitive Impairment

Enhancements of standard elements of the transition record should be considered for individuals with moderate to severe dementia or for those who experienced delirium during hospitalization. In these situations, the transition record should clearly identify and provide contact information for any known family caregivers of the patient, including notation of which individuals are authorized to be surrogate decision-makers.70 There should be a stated determination as to what elements of the discharge instructions the patient can and cannot understand, along with an assessment of patient and caregiver resources and their capacity to adhere to the recommended discharge instructions.

If the patient is returning home and would benefit from aftercare in-home services, such as visiting nurse assistance, communication with this agency or individual should be noted in the transition record. If the hospital course included significant symptoms, such as acute disorientation, paranoia, or threatening behavior, or if there is a known history of such behavioral disturbances, then follow-up regarding both medical and mental health clinicians should be coordinated, with specific instructions for whom to contact if problems arise. Whenever possible, instructions regarding how to manage behavioral problems should be included, with particular

attention paid to any factors that might pose a safety risk to the patient or his or her caregivers.

If skilled short-term nursing home treatment is arranged, recommendations for eventual home care should be provided. Such instructions may benefit the nursing home clinicians at the time of transition. Similarly, if long-term residential nursing home care is planned after inpatient medical treatment, consider including all the aforementioned elements plus recommendations for nursing home staff regarding the psychosocial elements of care that might ease or hamper the patient’s comfort during the initial transition.24

Tailoring Strategies to Individual Patients and Settings

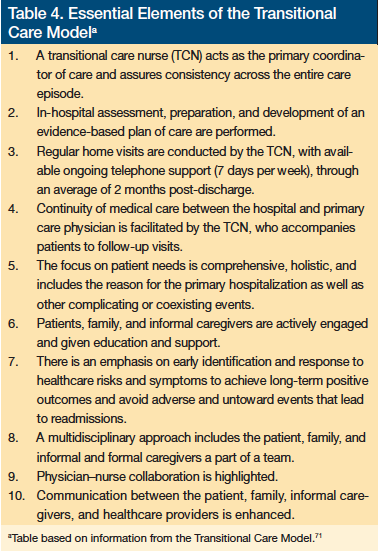

Several strategies for increasing the capacity of successful post-hospital transitions for vulnerable individuals with cognitive impairment are available to clinicians. Gains can be expected from simply increasing awareness of and reliance on the tool kits available through projects such as BOOST, RED, and CTI. Individual hospitals can develop staff education programs regarding the recognition and treatment of dementia and delirium; this education should be tailored to physicians, case managers, social workers, nurses, and other healthcare professionals. Hospitals or healthcare groups may choose to employ a new category of staff to function as a liaison between the hospital setting and the aftercare environment, such as the trained coach in the CTI or the transitional care nurse in Naylor’s Transitional Care Model (Table 4).3,17,71,72 Hospital administrators can also consider expanding the use of community visiting nurses to establish contact with these patients and their family caregivers in the hospital before discharge. These and other potential solutions will require continued empirical testing and validation of effectiveness.

Conclusion

When the medical or psychiatric inpatient treatment of an individual with dementia is completed, the next priority is the prevention of unnecessary rehospitalization. Financial costs of rehospitalization are high, and the burden patients and family caregivers experience when serial hospitalizations and multiple transitions of care occur is of great concern. Long-term goals could be achieved by improving aftercare service matching for individuals with cognitive impairment. Exactly how to effectively achieve such goals remains an important question; nevertheless, substantive steps have already been undertaken through the development of several of the projects outlined in this article, as well as publication of the TOCCC report, which makes evidence-based recommendations. Clinicians, hospitals, and caregivers can use these resources while they await the larger changes in policy and healthcare systems that are needed.

Dr. Epstein-Lubow acknowledges support from Butler Hospital, the American Federation for Aging Research, the John A. Hartford Foundation’s Center for Excellence in Geriatrics at Brown University, and the Surdna Foundation Fellowship Program at the Brown University Center for Gerontology and Healthcare Research. Dr. Fulton reports no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The IHI Triple Aim. 2011. www.ihi.org/offerings/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed January 30, 2012.

2. Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1529-1538.

3. Naylor M; National Institute on Aging. Enhancing care coordination: hospital to home for cognitively impaired older adults and their caregivers. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00294307. Updated December 7, 2011. Accessed January 30, 2012.

4. Gozalo P, Teno J, Mitchell SL, et al. End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13):1212-1221.

5. Alzheimer’s Association. 2009 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2009;5(3):234-270.

6. Lin PJ, Biddle AK, Ganguly R, Kaufer DI, Maciejewski ML. The concentration and persistence of health care expenditures and prescription drug expenditures in Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer disease and related dementias. Med Care. 2009;47(11):1174-1179.

7. Zhao Y, Kuo TC, Weir S, Kramer MS, Ash AS. Healthcare costs and utilization for Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:108.

8. Mor V, Besdine RW. Policy options to improve discharge planning and reduce rehospitalization. JAMA. 2011;305(3):302-303.

9. Callahan CM; National Institute on Aging. Modeling Alzheimer disease costs and transitions. NIH RePORTER; 2011. https://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?aid=7915670&icde=10304792. Accessed January 30, 2012.

10.Torian L, Davidson E, Fulop G, Sell L, Fillit H. The effect of dementia on acute care in a geriatric medical unit. Int Psychogeriatr. 1992;4(2):231-239.

11. Whitney JA, Kunik ME, Molinari V, Lopez FG, Karner T. Psychological predictors of admission and discharge global assessment of functioning scale scores for geropsychiatric inpatients. Aging Ment Health. 2004;8(6):505-513.

12. Woo BK, Golshan S, Allen EC, Daly JW, Jeste DV, Sewell DD. Factors associated with frequent admissions to an acute geriatric psychiatric inpatient unit. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2006;19(4):226-230.

13. Mercer GT, Molinari V, Kunik ME, Orengo CA, Snow L, Rezabek P. Rehospitalization of older psychiatric inpatients: an investigation of predictors. Gerontologist. 1999;39(5):591-598.

14. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):1582]. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428.

15. Gruneir A, Miller SC, Intrator O, Mor V. Hospitalization of nursing home residents with cognitive impairments: the influence of organizational features and state policies. Gerontologist. 2007;47(4):447-456.

16. Chugh A, Williams MV, Grigsby J, Coleman EA. Better transitions: improving comprehension of discharge instructions. Front Health Serv Manage. 2009;25(3):11-32.

17. Naylor MD, Hirschman KB, Bowles KH, Bixby MB, Konick-McMahan J, Stephens C. Care coordination for cognitively impaired older adults and their caregivers. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2007;26(4):57-78.

18. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Details for community-based care transition program. 2011. https://www.cms.gov/demoprojectsevalrpts/md/itemdetail.asp?itemid=CMS1239313. Accessed January 30, 2012.

19. US Department of Health and Human Services. Draft national plan to address Alzheimer’s disease. https://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/napa/NatlPlan.shtml. Accessed March 7, 2012.

20. Kuo YF, Goodwin JS. Association of hospitalist care with medical utilization after discharge: evidence of cost shift from a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):152-159.

21. Kane RL. Finding the right level of posthospital care: “We didn’t realize there was any other option for him.” JAMA. 2011;305(3):284-293.

22. Epstein-Lubow G, Gaudiano B, Darling E, et al. Differences in depression severity in family caregivers of hospitalized individuals with dementia and family caregivers of outpatients with dementia [published online ahead of print October 12, 2011]. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry.

23. Tew JD Jr. Post-hospitalization transitional care needs of depressed elderly patients: models for improvement. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2005;18(6):673-677.

24. Epstein-Lubow G, Fulton AT, Gardner R, Gravenstein S, Miller IW. Post-hospital transitions: special considerations for individuals with dementia. Med Health R I. 2010;93(4):125-127.

25. Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822-1828.

26. Courtney M, Edwards H, Chang A, Parker A, Finlayson K, Hamilton K. Fewer emergency readmissions and better quality of life for older adults at risk of hospital readmission: a randomized controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of a 24-week exercise and telephone follow-up program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(3):395-402.

27. Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178-187.

28. Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281(7):613-620.

29. Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial [published correction appears in J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(7):1228]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(7):675-684.

30. Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Leven CL, Freedland KE, Carney RM.

A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(18):1190-1195.

31. Coleman EA. The Care Transitions Program. 2011. www.caretransitions.org/ctm_main.asp. Accessed January 30, 2012.

32. Voss R, Gardner R, Baier R, Butterfield K, Lehrman S, Gravenstein S. The care transitions intervention: translating from efficacy to effectiveness. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(14):1232-1237.

33. The Care Transitions Program. Four Pillars®. 2007. www.caretransitions.org/four_pillars.asp. Accessed March 7, 2012.

34. Cummings SM. Adequacy of discharge plans and rehospitalization among hospitalized dementia patients. Health Soc Work. 1999;24(4):249-259.

35. Naylor MD, Stephens C, Bowles KH, Bixby MB. Cognitively impaired older adults: from hospital to home. Am J Nurs. 2005;105(2):52-61.

36. Society for Hospital Medicine. BOOSTing Care Transitions Resource Room: Overview. 2008. www.hospitalmedicine.org/ResourceRoomRedesign/RR_CareTransitions/CT_Home.cfm. Accessed January 30, 2012.

37. Whelan CT. The role of the hospitalist in quality improvement: systems for improving the care of patients with acute coronary syndrome. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(suppl 4):S1-S7.

38. Clancy CM. Reengineering hospital discharge: a protocol to improve patient safety, reduce costs, and boost patient satisfaction. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24(4):344-366.

39. Project Re-Engineered Discharge. Project RED—a randomized controlled trial at Boston Medical Center. 2011. www.bu.edu/fammed/projectred/. Accessed January 30, 2012.

40. Robison J, Curry L, Gruman C, Porter M, Henderson CR Jr, Pillemer K. Partners in caregiving in a special care environment: cooperative communication between staff and families on dementia units. Gerontologist. 2007;47(4):504-515.

41. Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(18):2148-2157.

42. Van Mierlo LD, Van der Roest HG, Meiland FJ, Dröes RM. Personalized dementia care: proven effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in subgroups. Ageing Res Rev. 2010;9(2):163-183.

43. Herbstman BJ, Pincus HA. Measuring mental healthcare quality in the United States: a review of initiatives. Curr Opin Psych. 2009;22(6):623-630.

44. Tew JD Jr. Enhancing transitional care quality for older adults discharged from psychiatric hospitals. The Practice Change Fellows Program Website. 2008. www.prac

ticechangefellows.org/documents/Tew_Summary.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2012.

45. Hanrahan N. Advanced practice psychiatric nurse–transitional care model to improve the quality of health care for individuals with serious mental illness. University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing Website. 2010. www.nursing.upenn.edu/faculty/grants/default.asp?pid=1201. Accessed January 31, 2012.

46. Jeste DV, Jin H, Golshan S, et al. Discontinuation of quetiapine from an NIMH-funded trial due to serious adverse events. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(8):937-938.

47. Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294(15):1934-1943.

48. Vigen CL, Mack WJ, Keefe RS, et al. Cognitive effects of atypical antipsychotic medications in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: outcomes from CATIE-AD. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(8):831-839.

49. Recupero PR, Rainey SE. Managing risk when considering the use of atypical antipsychotics for elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis. J Psychiatr Pract. 2007;13(3):143-152.

50. Epstein-Lubow G, Rosenzweig A. The use of antipsychotic medication in long-term care. Med Health R I. 2010;93(12):372, 377-378.

51. Daiello LA, Ott BR, Lapane KL, Reinert SE, Machan JT, Dore DD. Effect of discontinuing cholinesterase inhibitor therapy on behavioral and mood symptoms in nursing home patients with dementia. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7(2):74-83.

52. Kverno KS, Black BS, Nolan MT, Rabins PV. Research on treating neuropsychiatric symptoms of advanced dementia with non-pharmacological strategies, 1998-2008: a systematic literature review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(5):825-843.

53. O’Connor DW, Ames D, Gardner B, King M. Psychosocial treatments of psychological symptoms in dementia: a systematic review of reports meeting quality standards. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(2):241-251.

54. Kong EH, Evans LK, Guevara JP. Nonpharmacological intervention for agitation in dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(4):512-520.

55. Lyketsos CG, Colenda CC, Beck C, et al; Task Force of American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. Position statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry regarding principles of care for patients with dementia resulting from Alzheimer disease [published correction appears in Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(9):808]. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(7):561-572.

56. Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Gozalo PL, et al. Hospital characteristics associated with feeding tube placement in nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2010;303(6):544-550.

57. Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Intrator O, Feng Z, Mor V. Decisions to forgo hospitalization in advanced dementia: a nationwide study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(3):432-438.

58. Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Kuo SK, et al. Decision-making and outcomes of feeding tube insertion: a five-state study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(5):881-886.

59. Givens JL, Prigerson HG, Kiely DK, Shaffer ML, Mitchell SL. Grief among family members of nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(6):543-550.

60. Epstein-Lubow G, Davis JD, Miller IW, Tremont G. Persisting burden predicts depressive symptoms in dementia caregivers. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2008;21(3):198-203.

61. Schulz R, Martire LM. Family caregiving of persons with dementia: prevalence, health effects, and support strategies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12(3):240-249.

62. Beach SR, Schulz R, Yee JL, Jackson S. Negative and positive health effects of caring for a disabled spouse: longitudinal findings from the caregiver health effects study. Psychol Aging. 2000;15(2):259-271.

63. Ory M, Yee J, Tennstedt S, Schulz R. The extent and impact of dementia care: unique challenges experienced by family caregivers. In: Schulz R, ed. Handbook on Dementia Caregiving: Evidence-Based Interventions for Family Caregivers. New York, NY: Springer Publishing, 2000:1-32.

64. Burton LC, Newsom JT, Schulz R, Hirsch CH, German PS. Preventive health behaviors among spousal caregivers. Prev Med. 1997;26(2):162-169.

65. Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA. 1999;282(23):2215-2219.

66. Christakis NA, Allison PD. Mortality after the hospitalization of a spouse. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(7):719-730.

67. Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(2):P126-P137.

68. Fulton AT, Epstein-Lubow G. Family caregiving at the end of life. Med Health R I. 2011;94(2):34-35.

69. Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of care consensus policy statement American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College of Emergency Physicians, Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971-976.

70. Fitzgerald LR, Bauer M, Koch SH, King SJ. Hospital discharge: recommendations for performance improvement for family carers of people with dementia. Aust Health Rev. 2011;35(3):364-370.

71.Transitional Care Model. Key elements. www.transitionalcare.info/AbouKeyE-1804.html. Accessed March 8, 2012.

72. Bradway C, Trotta R, Bixby MB, et al. A qualitative analysis of an advanced practice nurse-directed transitional care model intervention [published online ahead of print September 9, 2011]. Gerontologist. doi:10.1093/geront/gnr078.