To the Point: Meeting Vaccination Quality Measures for Older Adults

Today’s long-term care (LTC) providers have an increasing myriad of vaccines available for their LTC residents—treatments with critical clinical benefits, especially for older adults. At the same time, accessing these treatments is not always easy, leaving many patients unable to receive those benefits and making it difficult for providers to reap the associated direct and indirect financial incentives tied to vaccine use. These financial incentives are delivered through the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS)—Medicare’s voluntary reporting program—and through newer reimbursement models, such as accountable care organizations (ACOs), which provide bonus payments based on specific outcomes.

Many of the target outcomes were derived from clinical guidelines developed by specialty societies and organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)1 and the Immunization Action Coalition.2 Although these guidelines are appropriate for many older adults, clinical exceptions do exist. The way outcomes are measured neglects to countenance these exceptions, and this places an additional burden on geriatric providers to ensure that they reach every patient for whom these treatments are appropriate.

Achieving target outcomes begins with understanding current clinical guidelines and coverage rules so that the “right” patients are identified and have access to the appropriate vaccines. Given the variety of treatment sites and infrequent dosing of many vaccines, tracking systems are needed to assure that none of these “right” patients are overlooked.

Quality Measures

Under the PQRS, Medicare distributes bonus payments to providers who achieve better than an 80% rate on at least three quality measures that were established based on current clinical guidelines. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 made several changes to the PQRS.3 In 2011, providers who reported on designated quality measures were eligible for a bonus payment totaling 1% of allowable Medicare Part B fee-for-service charges (FFS). For 2012 through 2014, the bonus payment amount decreases to 0.5%. In addition, physicians who meet the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS’) maintenance of certification criteria are eligible for an additional 0.5% from 2011 to 2013. Beginning in 2015, the PQRS becomes mandatory and instead of rewarding compliant providers with bonus payments, providers who do not successfully report on quality measures will incur a penalty of 1.5% of allowable FFS charges; the penalty imposed increases to 2% for 2016 and beyond.

The three measures can be satisfied just by focusing on vaccines, with the PQRS outlining the following targets for vaccination:

- Preventive Care and Screening: Pneumonia vaccination for patients 65 years and older

- Percentage of patients 65 years and older who have ever received a pneumococcal vaccine

- Preventive Care and Screening: Influenza immunization for patients 50 years and older

- Percentage of patients 50 years and older who received an influenza immunization during the flu season (September-February)

- End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD): Influenza Immunization in patients with ESRD

- Percentage of patients 18 years and older with a diagnosis of ESRD who received an influenza vaccine at a visit for dialysis between October 1 and February 28, or who reported having previously received an influenza immunization.

Currently, the provider’s rate of PQRS compliance with a specified measure is the percentage of his or her patients eligible to receive the measure or outcome who successfully do so. Within a specific geriatric practice, some patients who appear to meet eligibility criteria for a measure may not be appropriate candidates for the specified outcome, yet current PQRS calculation methods do not accommodate these exceptions. As a result, providers must work especially hard to ensure that every older patient for whom a particular measure is appropriate achieves the target outcome.

The PQRS is not the only set of quality measures that geriatric providers face; the CMS’ Minimum Data Set, Version 3.0 (MDS 3.0), tracks vaccination rates and other quality measures. Specific questions regarding influenza and pneumococcal vaccines are found within Section O: Special Treatments, Procedures, and Programs of the MDS. In contrast to the PQRS, the MDS 3.0 allows certain nursing home residents to be excluded from the quality measures, such as those who have medical contraindications or who decline the proffered treatment. Managed care organizations, such as ACOs, are increasingly applying measures tracked by the PQRS and MDS 3.0 as a means of encouraging appropriate care, especially those measures likely to reduce avoidable medical expenses.

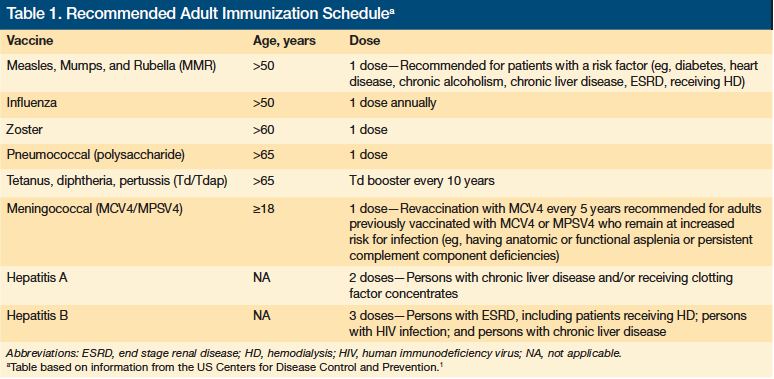

The quality measures, including those related to immunization, stem from accepted best practices that derive from recognized clinical guidelines provided by organizations such as the CDC. Table 1 outlines the CDC’s current immunization recommendations for older adults.1 Given the advanced age of the typical LTC resident, most of the CDC recommendations on vaccination will apply to the majority of residents. It is up to LTC providers to make sure patients for whom the recommended vaccinations are appropriate receive them.

Continued on next page

Accessing Vaccines

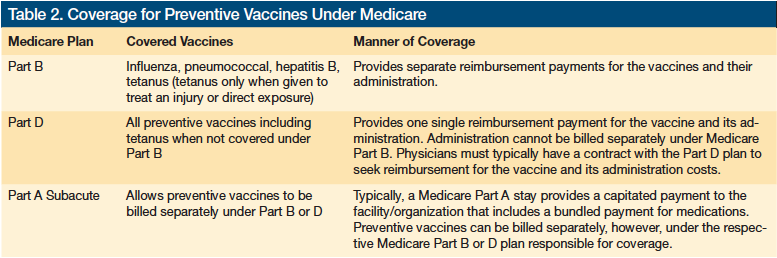

Knowing the immunization measures that providers are accountable for meeting is just the start—gaining access to the vaccines requires understanding Medicare’s coverage provisions, which are not always straightforward. For example, vaccines are covered under Medicare Part B and Part D, but they are typically not covered under Part A (Table 2). Vaccines that are covered under Part B are not covered under Part D.

Vaccine Coverage Under Medicare Parts B and D

Medicare Part B was introduced to provide coverage for specific vaccines, such as influenza, pneumococcal, and hepatitis B. In addition, tetanus is covered under Medicare Part B when directly related to the treatment of an injury or direct exposure to Clostridium tetani. In 2006, Medicare Part D was introduced, which allows beneficiaries to obtain prescription drug coverage—including preventive vaccines not covered under Part B—through subscription to a Medicare-approved private plan. Under Part B, Medicare reimburses providers separately for the cost of the vaccine and for the fee to administer it.4 In contrast, Part D plans authorize a single payment that encompasses the cost of the vaccine and its administration. This approach complicates matters for providers, who typically do not have a contractual relationship with all the Part D plans, and can make getting reimbursed a challenge.

Providers operating in the nursing home setting have a somewhat easier time accessing vaccines than those in the community setting, as the latter providers do not have the nursing home staff to take the lead. In the nursing home, the physician writes an order and the nursing home handles procuring the vaccine, administering it, and billing Medicare. In the community setting, the physician must purchase the vaccine, have his or her nursing staff administer it, and then bill Medicare. This added administrative and financial requirement makes providing vaccinations in the community setting more challenging than in the nursing home setting.

Accessing vaccines covered under Medicare Part D, such as the herpes zoster vaccine, is complicated for providers in the community. The community practice physician can give his or her patient a prescription, which the patient takes to a pharmacy to have filled. The patient can have the vaccine administered at the pharmacy, if available, or return with it to the physician’s office for administration. For vaccines covered under Part D, the physician’s office cannot buy the vaccines and then seek reimbursement under Medicare. Part D vaccines are only paid for by Part D plans, making it difficult for physicians to get paid. In addition, the physician’s office also cannot request reimbursement under traditional FFS Medicare for administering a vaccine covered under Part D, because this fee is incorporated in the amount that the Part D plan pays to the supplier of the vaccine. A growing number of programs are emerging to help providers navigate their relationship with Part D plans and overcome barriers to providing Part D subscribers with the appropriate vaccinations.4 In the nursing home, the vaccine is paid directly via the Part D plan to the institutional pharmacy, but the nursing staff cannot bill Medicare Part B for its administration, which is included in the Part D payment. The nursing home must work with their institutional pharmacy to receive reimbursement for administration since this was included in the payment made to the institutional pharmacy from the Part D plan.

Vaccine Coverage Under Medicare Part A Subacute Stay

In addition to confusion over vaccine coverage under Medicare Parts B and D, many providers are confused about coverage under Medicare Part A, which covers qualified stays at skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). Confusion arises from the erroneous belief that all pharmaceuticals administered at a nursing home—including vaccines—are covered under the bundled Medicare Part A Subacute prospective payment system (PPS).

Vaccines that are preventive services, which are those services considered reasonable and necessary to ward off occurrence of a designated condition are covered under the applicable Part B or Part D benefit and are never covered under Part A. Thus, when a resident covered under the Part A SNF provision receives a preventive vaccine for pneumococcal pneumonia, the vaccine is covered under Part B and is not the financial reasonability of the nursing home.

Signed Consent

Although coverage issues pose genuine barriers to vaccine access, the belief that signed consent is needed from residents represents an imagined barrier. The misperception likely arises from the fact that pediatric vaccines carry a signed consent requirement. Signed consent is not required of adult patients prior to receiving a vaccination or any other injectable medication. Verbal consent is sufficient in these cases. Assuring that older adults receive their needed vaccines is difficult enough without fabricating obstacles.

Tracking Treatment

Tracking vaccines is vital, especially for older adults who are more likely to be treated by multiple providers. One hopes that this process will become easier as a result of the large investment in health information technology available to Medicare providers and an increased focus on transitions of care.

Medication reconciliation at hospital discharge is a critical component of effective tracking. It is all too easy for treatments to get lost during transitions of care, especially for medications that are dosed infrequently. For example, hospitals have been charged with assuring that at-risk older adults treated at their facility are vaccinated against pneumonia; it is important that a record of this procedure returns to the nursing home with the resident.

Although it is expected that hospitals, physicians, and other providers will increasingly be more forthcoming with information during transitions of care, providers on the receiving end of a transition from one provider to another will need to take steps to prevent loss of data regarding vaccinations and other treatments. This will require developing a communication tool that assures a complete record of the care received.

Conclusion

When caring for older adults, closely focusing on vaccination measures provides a simple but effective way to help satisfy requirements for quality reporting and improve patient outcomes. Providers are being held accountable by various payers, including CMS, for vaccines as an outcome measure. Although the failure of PQRS calculations to account for patients not suited or unwilling to receive a particular vaccination is a barrier to achieving reporting goals, this obstacle can be overcome by making concerted effort to ensure that all patients who are eligible or willing are vaccinated appropriately. Accomplishing this will require understanding and managing coverage issues and tracking outcomes. Communicating with patients and other providers about transitions of care and documenting this information will also become increasingly important if physicians are to evade the looming financial penalties for failing to meet payers’ quality reporting objectives regarding vaccines.

Dr. Stefanacci served as a CMS Health Policy Scholar for 2003-2004, is associate professor of health policy, University of the Sciences, and a Mercy LIFE physician, Philadelphia, PA; and is chief medical officer, The Access Group, Berkeley Heights, NJ.

The author reports no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended adult immunization scheduled—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(4):1-4.

2. Immunization Action Coalition. Summary of recommendations for adult immunization. https://amda.com. Published January 2011. Accessed November 23, 2011.

3. US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Physician quality reporting system. https://www.cms.gov/PQRS. Updated October 17, 2011. Accessed November 23, 2011.

4. Stefanacci RG. Creating artificial barriers to vaccinations. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2005;6(5):357-358.